2/4 Welcome to Atlanta

Atlanta in the late 1970s was a city of contrasts, where Southern roots were intertwined with surges of new development. The opening of the first MARTA rapid rail line and the rise of the BellSouth Center were physical manifestations of the city’s growth.

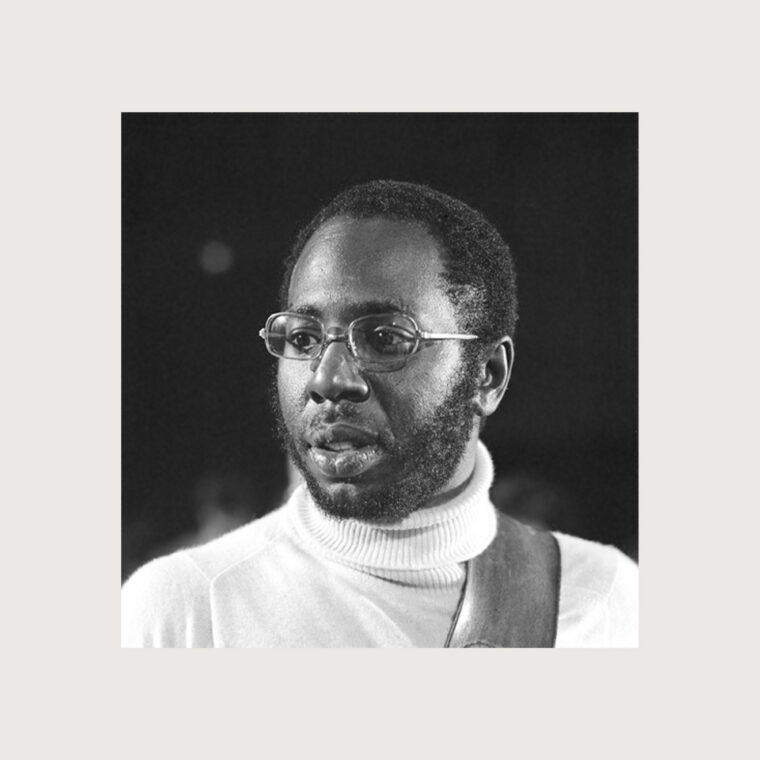

As Atlanta hummed with the rhythms of change and modernity, music industry veteran John Abbey found himself amid his own personal and professional life transformation. His journey, rich and eclectic, began in a working-class neighborhood in London, where he was born during World War II on July 8, 1945. A mechanic father and a Swedish homemaker mother raised Abbey with a strong work ethic. He was asked to take on responsibilities and contribute to the family from an early age.

His uncle, who ran a record shop and had a passion for jazz, was a significant influence. Working in the shop on Saturdays, Abbey was paid in records, not cash. In this environment, his uncle introduced him to artists like Fats Domino. This exposure was crucial in shaping his musical tastes and later career in the music industry.

Abbey’s foray into the music industry began in the 1960s with writing for a blues-focused fan magazine, a modest start that marked the beginning of a remarkable career. His path led him to start Home of the Blues, which evolved into the influential Blues & Soul magazine as soul music rose in popularity.

Expanding his reach, Abbey delved into music promotion, working with icons such as Al Green and Barry White and pivotally helping introduce soul music to the UK through record importing and label management.

While working as publisher and editor of Blues & Soul, the personal dimension of Abbey’s life took a major turn when he was introduced to singer Tamiko Jones during a phone interview. Jones, who had a hit with 1975’s “Touch Me Baby (Reaching Out For Your Love),” went on to release “Let It Flow” on Contempo in 1976, a label Abbey owned at the time.

“Sometimes you talk to someone even on the phone, and you develop a connection,” Abbey said. “And I mean, I must have interviewed 500 people before her. I was divorced at the time. So, you know, there were no words; it was just something. After we’d done the second interview and I was going to New York, I said, ‘Well, you know, maybe sometime we’ll meet,’ and she said, ‘Yeah, sure.’”

He and Jones finally met when Abbey visited New York on music-related business. “We had dinner and went from there,” he said.

This connection blossomed into a relationship and marriage in 1977, leading Abbey to move to metro Atlanta. Jones lived in East Point, next to producer Dave Crawford, in a community politically connected to figures such as Maynard Jackson and A. D. King, Martin Luther King’s brother. This move coincided with Blues & Soul‘s relocation to the United States.

Atlanta’s welcoming atmosphere and growing reputation as a music center were important to Abbey. He said, “Where we lived in East Point, at that point, was still 50-50. There were many white folks who lived there; there were Black folks.”

“I can’t honestly say I remember one occasion where anybody said anything derogatory. I don’t think anybody in the neighborhood saw anything different. I mean, we had a dog I brought across from England who we’d both take out for a walk, and people would be polite,” he said.

The relationship with Jones didn’t last, but Abbey said, “If it wasn’t for her, I wouldn’t be in Atlanta.” “So, I’m grateful for that. My life changed because of it, and I think her life changed because of it. We were good for each other for the time we were together. I hope she’d say the same.”

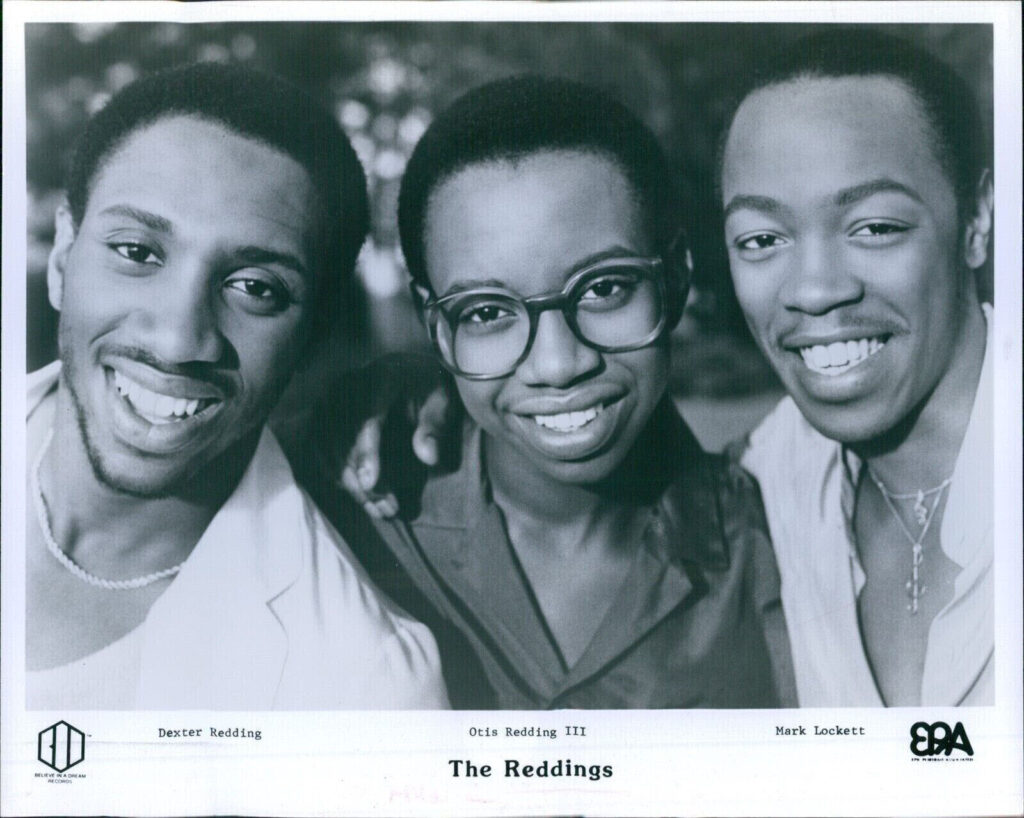

As Abbey’s time with Jones concluded, another chapter began in his life, both personal and professional. While in Helsinki, Finland, on a European tour with the Reddings, a funk, soul, and disco band helmed by Otis Redding’s sons, he met Nina Easton. She was a public relations manager for CBS Records, and her “get-it-done” attitude and charm left a lasting impression on Abbey. “I found her to be very efficient, but she was also very nice. She was good people,” he said. “By that time, the Tamiko thing was over, and the same thing, chemistry. I mean, despite all this, I’m still a man.”

Following the Redding’s tour, Easton took the initiative to visit Abbey in Sweden. As Abbey continued his tours, he often visited Helsinki during his off days, braving the Finnish winter to spend time with her. Eventually, she decided to relocate to the United States. A previous experience living in Texas and Easton’s fluency in English made the transition seem more feasible. She secured a job as a journalist with a Finnish newspaper, writing an international music column from America.

During this time, Abbey’s professional focus shifted as well. Blues & Soul magazine went on a long hiatus, and he worked as a consultant for a variety of American companies. Abbey also started organizing European tours from America, leveraging his extensive network and experience in the music industry. Easton’s move to the U.S. and integration into the music journalism scene complemented Abbey’s ongoing endeavors.

In Atlanta, a city also undergoing its own transformation, Abbey found himself navigating a new romantic partnership and establishing musical connections that would shape his career trajectory.

“There were a lot of musicians moving into the city,” he said. “Curtis [Mayfield] had moved a couple of miles away from us. I got to meet William Bell and Clarence Carter. A lot of people moved into Atlanta, so, you could see the growth. ”

While Abbey and Easton’s relationship developed, Mayfield, Carter, and Bell found themselves at a crossroads, each dissatisfied with their record label relationships at the time. Recognizing Abbey’s extensive experience in the music industry, they individually approached him with a proposal that would alter the course of their careers.

“Each one of them kind of suggested, well, why don’t you start a record label,” he said.

“So, I thought about it and was working with a label out of Shreveport, Louisiana called Jewel. They had gone into bankruptcy, but Louisiana law is such that if a bank will finance a continuation of the company. So, the guy at the bank, Steve Pursley, said, ‘Why don’t you start a label? Jewel can distribute it. You can get a certain amount of funding from the bank because we can write it off.’”

When Abbey took the news to Carter, Mayfield, and Bell, they were enthusiastic about the venture.

“We started [what became] Ichiban as the umbrella company. And then, Clarence went on to record under Ichiban, the label, but we did a split thing. He also had a label called Future Stars. William always had Wilby, which he still has to this day. Then Curtis had Curtom. We had Curtom, Future Stars, and Wilby, and off we went,” he said.

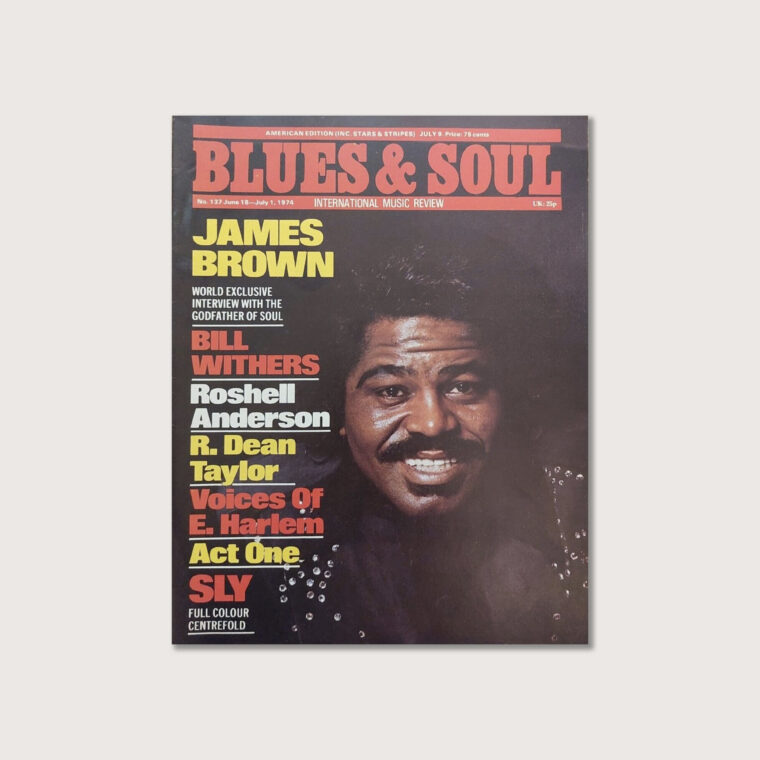

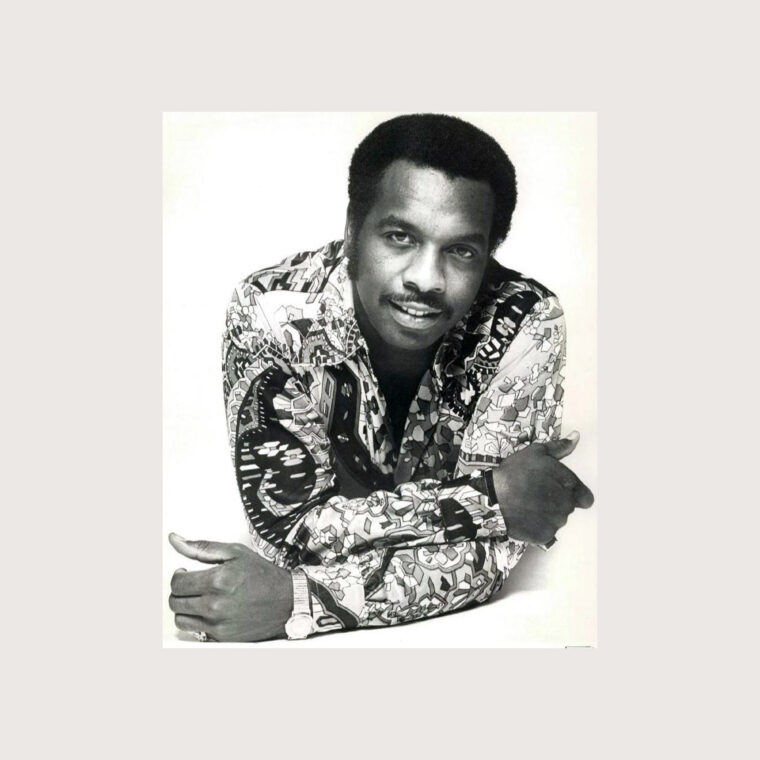

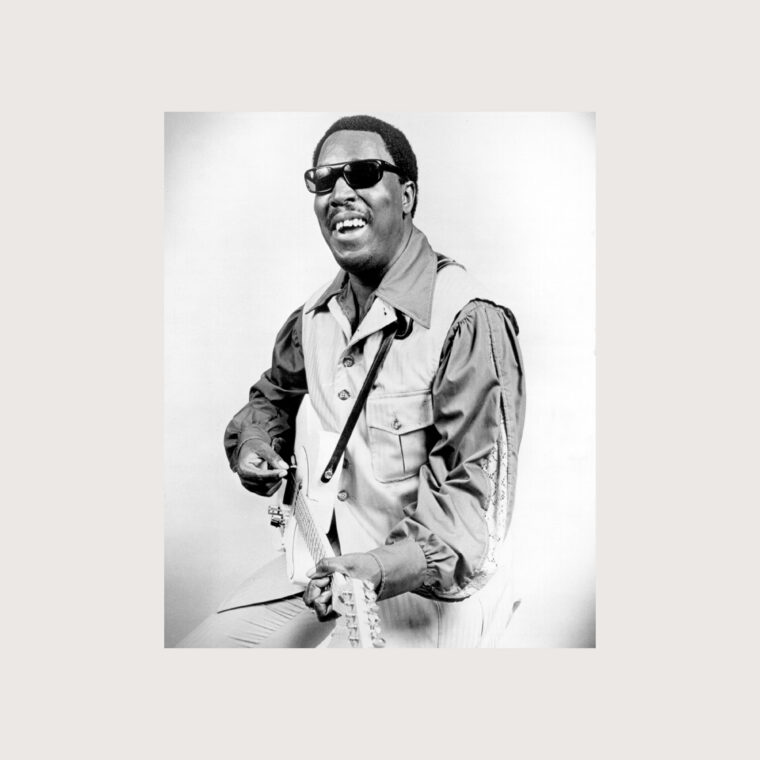

James Brown

Promotional still from 1985’s Rocky IV featuring James Brown performing “Living in America.” MGM

While on tour working as a promoter for James Brown in 1984, Abbey had a revelation about the importance of Japanese culture in this period that was vital to the naming of his new label. Brown would be besieged with fans every night, and all Abbey said he would hear was, “Ichiban soul brother. Ichiban soul brother.” In Japanese, “Ichiban” (一番) means “number one” or “the best.” The term is often used to denote superiority, top quality, or being the first in rank or position.

“I knew what Ichiban meant, and it was a time in history when everything Japanese was successful,” he said. “It was like, everything was being sold to Japanese companies, right?”

While flying with Brown, Abbey told him he wanted to call his new record company Ichiban. James Brown told Abbey it was a good idea.

“So, we were Ichiban, and I got Peter Barakan to write the character that says Ichiban. Then I got the graphic people to make everything look Japanese,” said Abbey.

Abbey’s decision to base Ichiban in Atlanta was convenient and strategic.

“[Mayfield, Carter, and Bell] were here; they were the bedrock of what we were doing,” he said.

“I live here, and I’ve always believed that if I want to do something, I’m either going to do it and win or do it and fail. If I fail, I’ll go back next week and try again,” he said. To me, geography wasn’t the issue, but having said that, I also saw Atlanta growing. It was a no-brainer. We could have gone to Memphis, but why?”

Next: 3 Started From the Bottom

In 1985, John Abbey and Nina Easton founded Ichiban Records in their Marietta, Georgia, basement. Facing challenges like flooding, they built an independent label with a strong foundation. Early hits, including Clarence Carter’s Strokin’, fueled growth, leading to moves from a basement to a 20,000-square-foot headquarters by 1992. Ichiban fostered a family-like atmosphere, with Abbey handling music and artist relations while Easton led marketing. Their strategic approach helped Ichiban become a major force in independent music.