1/4 The South Been Had Something to Say

When Outkast defeated Bone Thugs-N-Harmony to win the “Best New Rap Group” award at the 1995 Source Awards, Outkast members Big Boi in an Atlanta Braves baseball jersey, a dashiki-clad Andre Benjamin, and members of the Dungeon Family took the stage. To a barrage of boos from the audience, Atlanta-native Benjamin made brief remarks. He put the world on notice that “the South been had something to say.”

People have interpreted his statement as everything from a declaration that the South was coming for hip-hop’s crown to a wise, yet bold, declaration that the South would be the new tastemaker for rap from then on.

But really, Benjamin was trying to say that the South had a voice and that people needed to listen. In fact, the South had been vocal for quite a while.

Aerial view of downtown Atlanta looking north over Turner Field and Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, 1996. Cotten Alston, Cotten Alston Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The South’s hip-hop landscape, rich in its own traditions and styles, was frequently relegated to the background and seen more as a cultural outlier rather than a core contributor to hip-hop’s evolution.

This marginalization was not just a matter of geography but also of the unique musical qualities that characterized Southern hip-hop. The region’s distinct drawl, slower tempos, and storytelling style often clashed with the prevailing trends, which were dominated by the fast-paced, aggressive sounds of the East Coast and the smooth, gangsta funk (G-funk) style of the West Coast.

Yet, unbeknownst to those outside the region, Atlanta and other Southern cities nurtured a vibrant and dynamic hip-hop culture. It was not just an echo of what was happening in New York or Los Angeles; it was a unique entity thriving in local clubs, talent shows, and community centers. There, artists and producers experimented with new sounds, blending traditional hip-hop elements with local musical influences, crafting a style undeniably Southern in its essence.

“I like to say, ‘the South been had something to say,'” said Michael “DJ Smurf” Crooms, a DJ and music producer in Atlanta’s early years of hip-hop. “Before [André Benjamin said ‘The South Been Had Something to Say’], there was a whole community and a whole life — a whole music scene that existed here in Atlanta. It was underground, though.”

In Atlanta, talent shows provided a way for artists to display their rap, DJing, and dancing skills. Organized dance crews, emerging from community centers, high schools, and skating rinks such as the now-closed Jelly Beans, helped create and popularize dance moves such as the “Bankhead Bounce” and the “Yeek.”

Atlanta also had an energetic mixtape scene. Mixtapes have long been the cornerstone of hip-hop culture. They allow artists to experiment with new sounds, show off their skills, and nurture a fanbase. Many of the mixtapes in Atlanta’s early hip-hop culture in the 1980s and early 1990s were bass-heavy.

“No disrespect to Outkast, Organized Noize, and LaFace, but that sound didn’t even exist here,” said DJ Smurf. “The part that came before them was all up-tempo booty shake, Atlanta bass, Miami bass. That was the sound that existed from the artists that were here.”

Bass music is raw and percussion-driven. The sound is primarily steered by producers, not MCs, and focuses more on instrumental elements, especially powerful bass and sharp hi-hats, than on complex lyrics.

Bass is loud, bold, and unapologetically energetic. Consequently, it isn’t meant for subdued listening through small earbuds; it is made to be played on powerful subwoofers and shared with a whole community. The iconic bass sound often originates from a Roland TR-808 drum machine, giving rise to the term “808” used today to describe the genre’s signature sound. Atlanta bass blends the Miami sound with the slower tempo of contemporary R&B tracks or vocals, often adopting a more melodic vocal style.

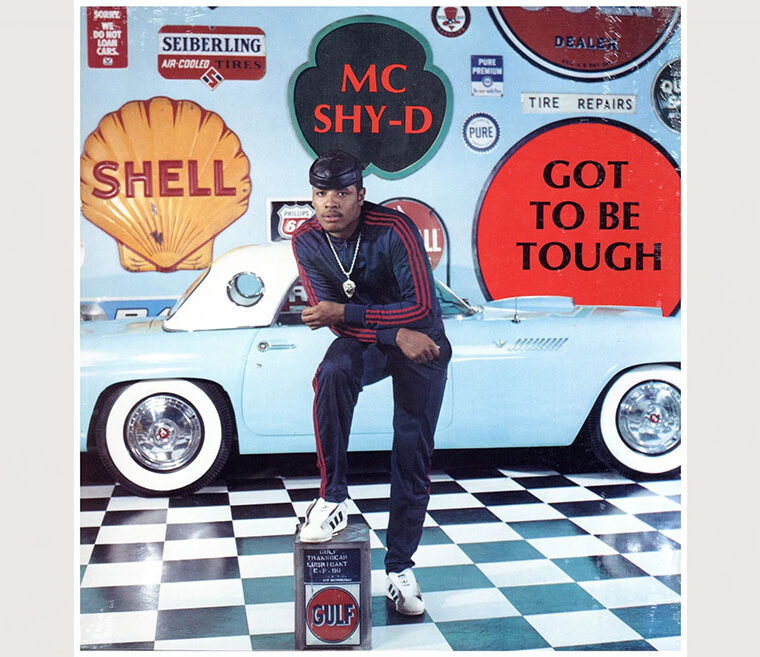

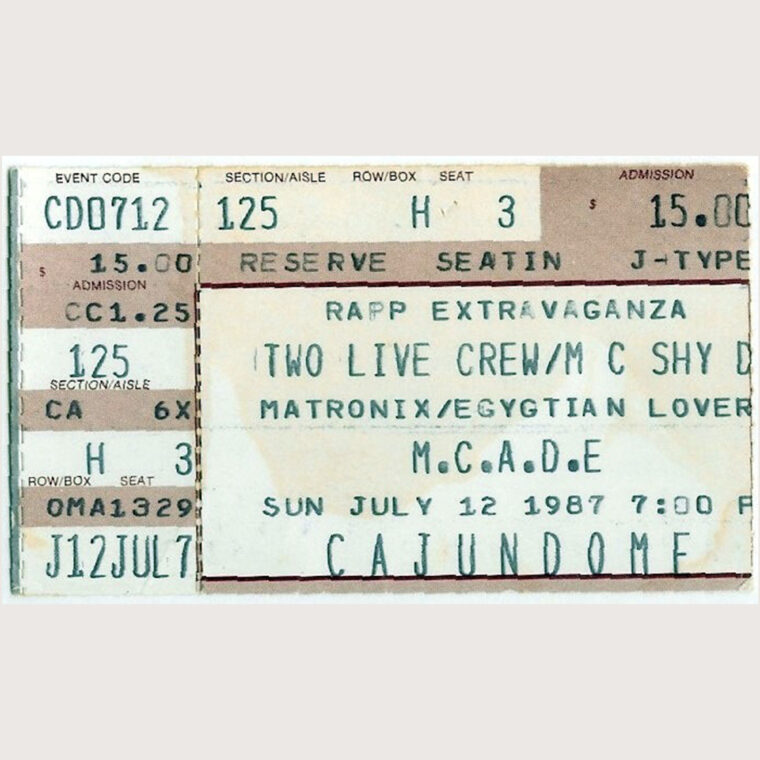

New York-born, Atlanta transplant MC Shy-D was one of the first artists in Atlanta to make it big with an Atlanta-style Miami bass record, 1987’s “Got to Be Tough.” The album was released on Luke Skywalker Records, a label created by Luther Campbell of 2 Live Crew. MC Shy-D’s rise to fame proved that Atlanta’s hip-hop had the style and substance to compete on a larger stage. His success was like a bat signal for upcoming artists, signaling the arrival of Southern hip-hop as a force with which to be reckoned.

"America Has A Problem (Cocaine)"

Kilo

Kilo, another name synonymous with Atlanta bass, was more than just an artist; he was an innovator who seamlessly blended Miami bass with the smoother melodies of R&B. His music captured the energy of Atlanta, and his songs became local anthems. His flair for combining aggressive bass lines with catchy hooks set a new standard in the South, carving out a niche that would influence generations of artists.

In addition to MC Shy-D and Kilo, other artists who created and popularized the Atlanta bass sound include MC Breed, DJ Kizzy Rock, Raheem the Dream, A-Town Players, the Hard Boys, Success-N-Effect, and DJ Smurf.

As Southern hip-hop artists began changing the game with their music, Ichiban Records emerged as a key force fueling this musical revolution. Established in 1985 in metro Atlanta, Ichiban Records was more than just an independent label; it was a platform that echoed the South’s burgeoning voice in hip-hop.

Ichiban became the go-to place for artists seeking to make a name for themselves in hip-hop. Unlike some businesses that chase trends, Ichiban didn’t merely ride the wave of Southern hip-hop; it actively shaped it.

“Shy D had some troubles, went away for a bit, and when he came back, he didn’t have a record deal. That’s when he found Ichiban,” said DJ Smurf. “They were the go-to label in Atlanta; the home for many emerging acts in the area.”

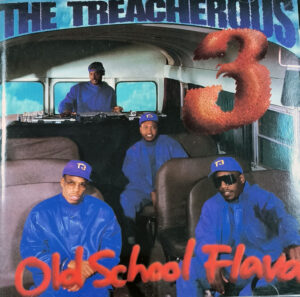

Theodore “DJ Easy-Lee” Moy’e, a pioneering DJ from the influential hip-hop group The Treacherous Three, confirmed Ichiban’s role in fostering the so-called Dirty South hip-hop sound. “If you came through Atlanta and you were a rapper or in the entertainment industry between the 90s and 2000s, you could not have not worked with Ichiban in one capacity or another,” he said.

“Ichiban helped change the narrative because it gave rappers, management companies, and a lot of athletes and drug dealers an opportunity to change what they were doing and get into the industry in one capacity or another,” he said. “Most athletes want to be rappers. Most rappers want to be athletes. Most drug dealers want to be in the industry in some capacity or another. And, because it was exciting, everybody gravitated to the industry and Ichiban was one that you could go to and get a fair hearing.”

At Ichiban, hip-hop artists found an opportunity to flourish, thanks partly to John Abbey, the visionary behind the label. More than just a businessman, Abbey was a music enthusiast who deeply believed in rap’s potential and capacity to evolve. His decision to invest in artists like Kilo and MC Shy-D was a testament to his belief in the power of Southern hip-hop.

“I saw that the Southern bass thing was coming. So, we had Kilo, we had Shy-D, and after that, we had other people who benefited,” said Abbey.

Shonda Jessie-Wheeler, Abbey’s former personal assistant, also highlighted the critical role of Ichiban in laying the groundwork for many artists and companies that later achieved national and international acclaim.

“A lot of people don’t even realize that Jermaine Dupri had a 12-inch that he wanted to put through Ichiban Records,” she said.

Ichiban Records played a transformative role in changing how national labels perceived and engaged with Southern talent. Its success in promoting Southern artists caught the attention of industry figures, including Clive Davis of Arista, facilitating the establishment of LaFace Records by Babyface and LA Reid.

DJ Smurf shared his perspective on the contrasting paths of major labels and grassroots efforts. “I always felt like that was cheating. I always looked at that like they got a bunch of money; they got budgets; they got all this. We had to go get it out the mud,” he said, underscoring the value of building success from the ground up with Ichiban.

Though the Atlanta sound that initially reached critical mass differed from what was popular locally, Jessie-Wheeler said the impact of pioneering local artists can’t be understated.

“I don’t think that without any of those, could you have had an Outkast or a Goodie Mob because when they first came out, everybody thought, ‘wait, they rap with like a little Southern drawl. It’s a little slow; the tempo is not quite [right].’ Even with bass music, it was like ‘bass music, booty music. Nobody’s gonna listen.’”

"Ooh Lawd"

DJ Smurf

Nevertheless, eventually, the cards aligned for Southern rap supremacy. Its influence has been significant in shaping the trajectory of subsequent Atlanta music trends, including Dirty South, which is known for its hard-hitting, aggressive beats and lyrics, Crunk, Snap and Trap. All these genres speak to Southern rap’s impact in the broader hip-hop landscape.

“And here it is 30 years later, plus, and it’s still one of the most viable genres out there,” Jessie-Wheeler said of Southern hip-hop.

She added, “Atlanta does not get the props I think it deserves a lot of times when it comes to what we have contributed to the music landscape. We are getting there because now everybody wants to call Atlanta home.”

She welcomed newcomers but urged respect for the city’s rich musical heritage: “Okay, we’ll embrace you. That’s fine, but don’t sleep on our history.”

Next: 2 Welcome to Atlanta

In the late 1970s, Atlanta underwent rapid growth with developments like the MARTA rail line and the BellSouth Center. Amidst this, London-born music industry veteran John Abbey relocated to Atlanta. His passion for jazz, shaped by his uncle’s record shop, led him to launch Blues & Soul magazine and promote artists like Al Green and Barry White. His deep connection to soul music and industry experience culminated in the founding of Ichiban Records in 1985. The label became instrumental in shaping Atlanta’s music scene, fostering Southern hip-hop and R&B talent.