4/4 The Next Episode

Twenty-six years ago in 1999, as the world teetered on the brink of a new millennium, a sense of uncertainty and excitement electrified the air. The Y2K bug, a technological specter threatening to plunge the modern world into chaos at midnight on December 31, loomed large in the public consciousness. Amidst the backdrop of a potential digital apocalypse, the music industry was undergoing its own seismic shifts.

Ichiban faced these crossroads of change head-on. The label, known for its innovative approaches and community-centric ethos, was poised at the edge of the future, ready to dance into the unknown.

The question on everyone’s mind was simple yet profound: What would the new millennium bring for Ichiban, and how would it navigate the uncharted territories of a world bracing for a digital revolution or a technological meltdown?

The short answer is closure.

However, as the clock ticked towards the year 2000 and the rest of the world was gripped by excitement and trepidation, it wasn’t changing technology that led to Ichiban’s demise but bad business decisions.

Just four years earlier, Ichiban was riding high.

The label had carved out a unique niche, offering a full spectrum of services that rivaled major labels, earning it the moniker of a “minimajor.” Ichiban was releasing 75 to 100 albums annually, matching and, at times, surpassing the output of many major labels.

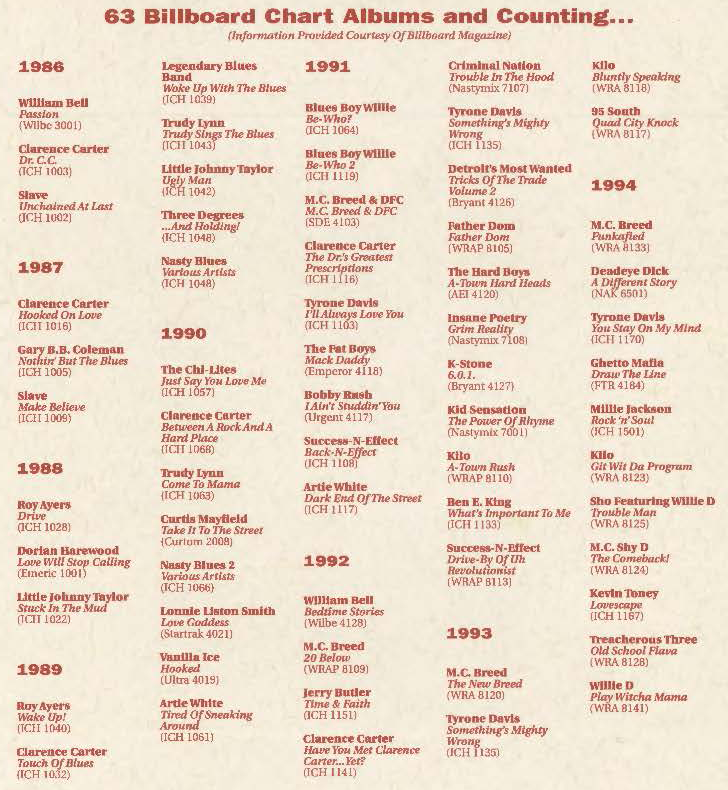

Though the label was founded focusing on blues and soul music, by 1995, Ichiban had grown far beyond its initial offerings. The label’s portfolio featured artists from a range of genres, including pop, rap, alternative, blues, and jazz. More than 60 of these releases made their mark on the Billboard charts.

Ichiban also marked its 10th anniversary in 1995. Ichiban’s achievements and philosophies were recognized in an April 8, 1995, special section in Billboard Magazine that included interviews and stories that underscored the label’s history, philosophies, and industry relationships.

Comments from industry partners and artists painted Ichiban as a company of significant impact, valued for its independence, and known for treating artists and staff with respect and integrity.

Ichiban celebrated the milestone with an open house that drew an international crowd, highlighting Ichiban’s global influence. Reflecting on the label’s 10th anniversary, Abbey was nostalgic.

“That was my proudest moment,” Abbey said, reminiscing about the event. “The fact that little me from London had all these people flown in from all over the world to our warehouse, and in my warehouse were those five guys.”

Abbey detailed the event. “We had distributors, artists, and all sorts of people coming in from everywhere. There were photographers and all kinds of people.”

“The most remarkable thing,” Abbey said, “was seeing Curtis in his wheelchair, Tyrone Davis, William Bell, Clarence Carter, and Ben E. King all in one room. They were five of the greatest talents the world will ever know, but also five of the nicest people I have had the pleasure to work with. And to see them all in one place, in my warehouse during that anniversary in 1995.”

The celebration was also the beginning of the end for Ichiban. “The biggest mistake we made stemmed from that day,” Abbey said.

“EMI came to our 10th anniversary. It was covered by the Marietta Journal and the Atlanta Journal. It turned some heads, Nina’s especially, but she wasn’t the only one. The danger in our business, and for artists, too, is when you start believing your own press release. That’s when your downfall begins.”

Easton was the driving force behind an eventual partnership with EMI.

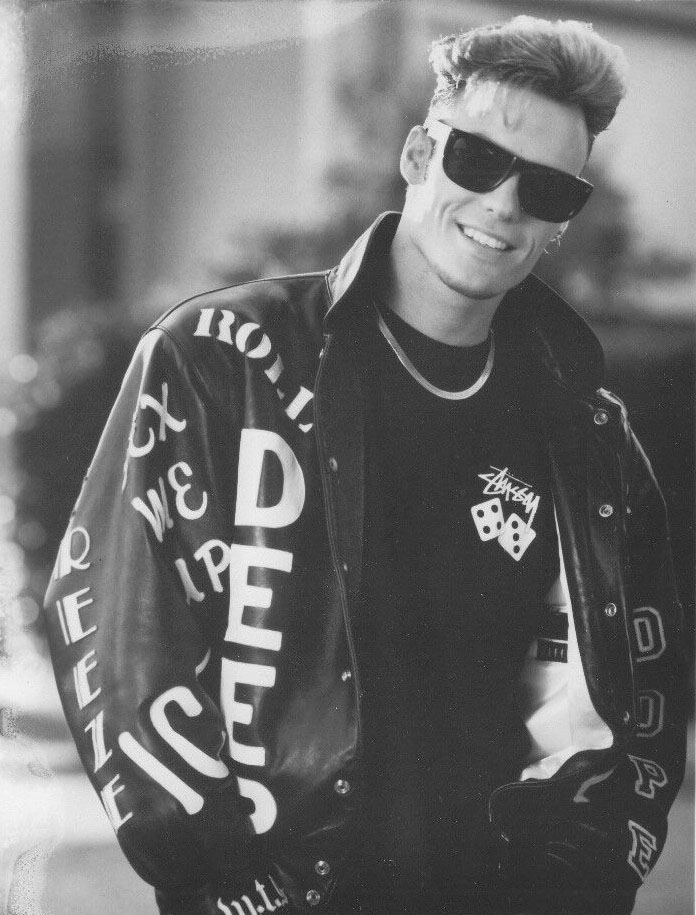

Ichiban previously collaborated with EMI, working with artists like Vanilla Ice. In 1989, Vanilla Ice released his debut album, Hooked, on Ichiban before transitioning to EMI’s subsidiary, SBK Records, for subsequent albums. His breakout hit, “Ice, Ice Baby,” which eventually went platinum, originally appeared on Hooked.

Despite this past relationship with EMI, Abbey was reluctant to work too closely with the company.

“I refused to let them distribute our Black music division. I knew they weren’t going to do what needed to be done. I knew they weren’t going to treat the artists the way that I wanted them to be treated,” he emphasized, taking responsibility for the decisions he made.

Eventually, Abbey was persuaded to go along with the EMI partnership to disastrous results.

“They promised the world, and they gave us Cleveland,” Abbey said. “When you start believing the big man, you got a problem.”

"New Age Girl"

Deadeye Dick

Abbey expressed regret over not taking money from EMI, considering the financial burden that Ichiban later faced. “I think here’s why I wish I’d taken the money because I would have been spending their money and mine. The drain on the cash flow was so much, and we weren’t getting the return,” he explained, acknowledging the financial difficulties encountered during this phase.

The label’s foray into the rock and roll genre, particularly with Dead Eye Dick’s hit on the “Dumb and Dumber” soundtrack, marked a significant shift in Ichiban’s image and operations.

“Suddenly, the world saw us as a rock and roll label. And it’s like we’re not,” said Abbey.

The venture into rock and roll presented a new set of challenges for Abbey and Ichiban. “When these rock and roll people came in, first of all, I had no idea what they were talking about. Their approach to everything was different. I didn’t get the feeling that the music was the important thing.”

He also noticed a change within the company. “It wasn’t that there was less attention in-house, but you have people who were switching their focus from Kilo to some other act who had absolutely no commercial value,” Abbey noted.

Reflecting on his feelings during this time, Abbey said, “I feel like I was pushed off the cliff. As soon as Nina chose to leave, the EMI thing came to an end. I said, ‘I’m not going to continue,’ and they let me out, which was nice of them.”

Ichiban faced financial difficulties after the partnership with EMI dissolved, “We had an independent network still in place, but the industry was changing. I needed financing because the money had all been spent.”

Abbey tried to rely on his personal network for salvation. One of Ichiban’s staff members had a wife who was a corporate banker. She brought in investors and made promises with little follow-through.

“They lied. I wish I could lie that good. We were sitting there with the Ying Yang Twins and Lil Jon, ready to go. It was like being with a major.”

After failing to get additional funding, Abbey reached his breaking point.

“One day, I just said, I can’t do this anymore. So, we shut the building, and that’s how it ended. We went into receivership, and I worked with the receiver to make sure that the transition was smooth.”

Jessie-Wheeler acknowledged Abbey’s efforts during this challenging period. “John did a very, very good job trying to keep it afloat and keep us together, but sadly, it just wasn’t in the cards for us,” she said.

The label’s closure was a shock to everyone involved. “We were all heartbroken and shell-shocked. We had been on this incredible run, and suddenly, it felt like being told your favorite ride is being dismantled forever,” Jessie-Wheeler said.

She described the personal grief that followed. “There was a grieving process. You wake up and suddenly your purpose, the people you enjoyed being around, the creative journey you were on – it’s all gone. You’re left wondering, ‘What now? Where do I go? What’s my purpose?’”

Jessie-Wheeler also empathized with Abbey’s experience. “It was a somber moment. You don’t know who you feel worse for. I felt bad for myself but even more so for John. He had been building this baby a lot longer than I had been there.”

Lil' Jon and the Eastside Boyz

Landing/ artist marketing page on the Ichiban Records website.

When Ichiban began to falter, DJ Easy Lee wasn’t directly involved but heard various accounts of its decline. “I think internal issues played a big part in its downfall,” he said, indicating that he wasn’t present during the label’s final days to witness the events firsthand.

DJ Easy Lee’s immediate concern following Ichiban’s closure was to salvage any remaining products from his label. “I had three albums, including a Kool Moe Dee interlude album and others, which were never released. I knew there were at least 50,000 pieces of each, including vinyl, cassettes, and CDs,” he said. When he arrived at Ichiban’s premises, much of the product had been discarded. “I managed to retrieve about 400 pieces from the dumpster at the back,” DJ Easy Lee said.

The closure of Ichiban not only affected the distribution of music but also had a personal impact on DJ Easy Lee.

“It was a hurtful feeling, knowing that many people I knew still worked there. It wasn’t just about the business; families and jobs were affected. It’s the collateral damage of internal issues. I felt for them, but there was little I could do,” he said.

Despite these challenges, Abbey tried to keep calm and carry on. After the closure of Ichiban, Abbey pivoted to touring and international music promotions.

“I was still doing my tours. Nina was gone. I was here with the kids. And life goes on. You just find a way of getting through. I had a network of people around the world that I could work with.”

This global network played a pivotal role in his post-Ichiban career. “I took on an agreement with a company in Japan to book acts.”

This new focus not only provided a professional lifeline but also allowed him to heal from the past traumas associated with the label’s end.

“I was responsible for bringing acts over to Japan. I got to work with the Stylistics, Temptations, Ben E. King, and others. I had an apartment in Tokyo, which was nice. It was a way of letting me heal but still doing what I loved.”

“My mother was here to look after the children as they grew up. My kids came to Japan with me. They’d also travel around Europe, usually with Three Degrees, who I still work with to this day,” Abbey said, highlighting the support system that enabled him to balance his professional commitments with family life.

His career took another turn as he pursued further education. “I’ve also studied to be a lawyer and accountant. I’ve ventured into doing law, helping acts who have been cheated.” Abbey’s legal expertise became a new avenue to support artists, especially those who had faced financial exploitation.

“We’ve been able to make money,” Abbey said. “The Three Degrees being the best example. We now get paid. All the accounting and travel paperwork, that’s part of the tours I manage now.”

Vince Hart

Atlanta History Center

Post-Ichiban, others from the label went on to do great things as well.

Vince Hart ventured into different industries post-Ichiban. His journey saw him dabbling in the construction industry, sales, and later the hospitality industry. In 2017, he joined Atlanta History Center’s private events team. His role as an event operations and staffing manager allowed him to delve into and contribute to preserving Atlanta’s history.

Hart summed up Ichiban’s legacy underscoring the label’s commitment to diversity and nurturing local talent. “Ichiban, if nothing else, let the world know that independent labels can do a good job,” he said.

Theodore “DJ Easy-Lee” Moy'e

Atlanta History Center

After his time at Ichiban, DJ Easy Lee explored new avenues, becoming a consultant for various independent labels. His expertise in production management and live sound engineering has made him a sought-after professional.

He has worked as a production manager on projects such as BET’s “Black Girls Rock,” productions by David E. Talbert and Tyler Perry, and the Riverfront Jazz Festival. DJ Easy Lee is also a published author, with his book Poetry for the Body of Christ, and has ventured into acting, motivational speaking, and teaching. Entrepreneurially, DJ Easy Lee has owned and operated several businesses throughout his career, including a recording studio, management company, record label, and production company.

Currently, he owns and operates Moye’s in Douglasville, Audio Advantage, and Moyé Transportation, and he continues to tour with the old-school funk band Cameo.

Shonda Jessie-Wheeler

Atlanta History Center

Shonda Jessie-Wheeler’s journey post-Ichiban is another story of entrepreneurial success and personal happiness. She married Joe Wheeler, one of the members of Success-N-Effect and has been married to him for 30 years. She co-founded a company with Ed Strickland, involving herself in music festivals in Rochester, New York and securing a distribution deal through E1. Her company focused on signing labels and releasing albums.

Additionally, she has maintained a close working relationship with DJ Easy Lee, collaborating on various musical projects, including a Dallas festival. Jessie-Wheeler has also been actively involved with the Hip Hop Alliance, working alongside prominent figures like KRS One and Public Enemy. Moreover, she continues to offer music consulting services, staying deeply connected with Atlanta’s music scene.

Michael “DJ Smurf” Crooms

Atlanta History Center

DJ Smurf, also known as Mr. Collipark, shifted his focus to the production side of the music business, taking a step back from DJing. He played a pivotal role in the rise of artists such as Ying Yang Twins, Soulja Boy and Hurricane Chris. Recently, he has veered into the Southern Soul genre, working with artists such as King George.

However, his passion for DJing reignited as he adapted to the evolving music production landscape. DJ Smurf dedicated time to mastering new software and equipment, embracing technological advancements and ensuring his skills remain relevant and cutting-edge. Recently, DJ Smurf showcased his enduring talent and adaptability at One Music Fest.

Reflecting on his journey and the legacy of Ichiban Records, DJ Smurf acknowledges the label’s significant impact, stating, “I don’t think you can quantify the impact of Ichiban … it sparked other stuff.”

John Abbey

Atlanta History Center

When recounting his journey with Ichiban, Abbey said, “Had we not made the mistakes we did, Ichiban could have continued for another three to five years. But in hindsight, we probably would have ended up selling out. I made those calls, and it’s on me.”

“Maybe there’s good reason for all that happened. Every experience, good or bad, has a yin and yang, something to learn from. I’m thankful for the experiences and where they’ve led me, particularly in my personal life.”

He concluded on a hopeful note, “I hope all the people who worked with us see that period as a good time in their life and career. If they look back and smile, thinking of it as a good time, then I’ve achieved what I set out to do.”