3/4 Started From the Bottom

John Abbey and his life partner, Nina Easton, found their personal and professional lives intertwining in an extraordinary way as they embarked on their journey with Ichiban.

In the early days, Ichiban was a garage-based start-up in Marietta, part of Metro Atlanta. Their lean team comprised Abbey, Easton, and one dedicated soul handling radio promotions. Nestled midway down a slope, their base of operations was often subject to the whims of Southern downpours, leaving them wading through two inches of water in the garage to fulfill orders.

Despite the challenges, each album the fledgling label released, from Curtis Mayfield’s We Come in Peace to Clarence Carter’s Messin’ With My Mind, was not just a milestone but also a triumph.

Carter’s music, in particular, was crucial for Ichiban’s early success.” According to Abbey, Carter’s “Strokin,” which was released in 1986 on the album Dr. C.C., essentially laid the foundation for the label’s future.

“Without ‘Strokin,’ there’d be no Ichiban,” he said. “It sold forever. There wasn’t a week, there wasn’t a day that went by that we didn’t sell several boxes of it,” he said.

Frequent delivery truck visits alerted Abbey and Easton to the growth of their venture. It was clear that Ichiban needed its own space. In the interim, for those crucial business meetings, Abbey and Easton found refuge in restaurants, cleverly masking their home-based operations from the professional world.

“People assumed, ‘Oh, they’re Japanese; they must have money. Yeah, we’ll work with them.’”

So, there we are, sitting in my garage, two miles from here, with Japanese distributors calling [saying,] ‘we’d like to represent you.’ I know I could have gone with them, [but] no, I want[ed] to be independent. We’re gonna do it for ourselves. We’re gonna show these big guys what we can do,” Abbey said.

By 1988, the time was right for expansion. Ichiban set up its first official office in Marietta. This was a big leap, but the company’s continuous success meant it wasn’t long before they outgrew these new confines. The next year, Ichiban added a recording studio, KAIA. This studio became the birthplace of many of the label’s chart-topping releases.

In 1992, the ever-expanding Ichiban moved its headquarters to a new location in Kennesaw. This building, which was about 20,000 square feet (about four times the area of a basketball court), was carefully designed to cater to the company’s growing needs.

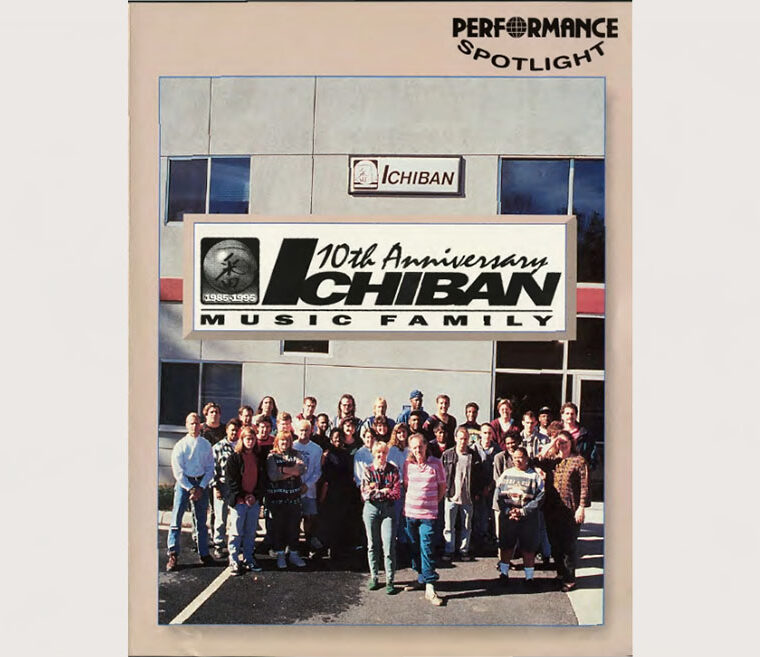

The Kennesaw headquarters buzzed with the energy of the “Ichiban family,” comprised of Abbey, Easton, and about 50 employees. Abbey and Easton were patriarchs of sorts. They formed a formidable duo, blending artistic passion with strategic marketing.

Abbey, deeply involved in the music, oversaw every musical element the label touched. “I was always the music person and the artist person,” he said. From R&B to hip-hop, every act passed through his discerning ears.

Easton complemented Abbey’s musical focus with her marketing acumen. Abbey acknowledged her critical role, saying, “Nina wasn’t the music person at that point at all. She was marketing, and she was absolutely excellent at it. Without her, [Ichiban] never would have made it.”

Further adding to the opposites-attract dynamic that made things work at Ichiban was each’s leadership style.

Shonda Jessie-Wheeler, Abbey’s assistant at Ichiban, remarked on Abbey’s unassuming nature: “He was not your typical label owner. If you ever saw John, you would not realize he owned that record label with Nina.”

DJ Smurf, another former Ichiban employee, echoed Jessie-Wheeler’s sentiments. He reflected on the company’s culture and particularly emphasized Abbey’s distinct leadership style. DJ Smurf recalled the major thing he learned from Abbey was to avoid flamboyance.

“He would come into the office dressed like he was still at the house,” DJ Smurf said, recalling Abbey’s modest attire.

“All of us came up there driving our little Jeeps and thought we were doing something, and we didn’t have anything. While the guy running the whole thing — you wouldn’t even know who he was. I learned how I carry myself because it’s not the loudest person in the room that’s really about that business.”

In contrast to Abbey’s easygoing demeanor, Easton was characterized by her assertive and punctual management style. Vince Hart, another former employee who was responsible for building relationships for the company in retail markets, referred to her as a disciplinarian.

He said, “Nina was the enforcer, if you will. She made sure everything ran on time.” Her Finnish background influenced her communication, and she often used phrases like “heads will chop” to emphasize the importance of efficiency and effectiveness.

The familial atmosphere at Ichiban extended beyond mere metaphor; it included actual relatives such as Easton’s brother, Mike Talvitie, overseeing production, and Abbey’s brother Gof, helming international operations.

Beyond their immediate family, Abbey and Easton extended a sense of kinship to their employees. Ichiban Records showed deep care for its staff members through generous gestures such as company-paid trips to international destinations, including Switzerland and Mexico.

Abbey spoke about the importance of family within the company, saying, “I think the camaraderie and the family atmosphere there was such [that] there was a genuine element of love within the building, and I think you felt that coming in.”

Within the walls of Ichiban Records, the familial bond and sense of camaraderie fostered by Abbey and Easton laid the foundation for an office alive with energy and possibility, where the unexpected was always around the corner.

DJ Easy Lee, who not only had Wrap Records, a label distributed by Ichiban, but also worked with the label in radio promotions, vividly recalled the artists who would walk through the label’s doors: Millie Jackson, Willie Clayton, Clarence Carter, and Theodis Ealey, among others.

“It was exciting,” he said, emphasizing the label’s status as one of the premier labels of the time in Atlanta.

Hart said that he was also awed by some of the artists who would come through Ichiban’s lobby, from Chuck D of Public Enemy waiting to discuss business ventures with Abbey to encounters with legends such as Kevin Bell from Kool & the Gang and Curtis Mayfield.

“I was kind of starstruck with [Bell] because, ever since I was a kid, [I listened] to Kool & the Gang,” said Hart. “And of course, some of the locals like Lil Jon would be up there a lot, and some of our own artists, Kilo, MC Breed. And knowing Curtis Mayfield personally. If I was around him 100 times, it was still like, ‘God, Curtis Mayfield, Super Fly.’”

"Gotta Get Mine"

MC Breed (feat. 2Pac)

Even Tupac Shakur spent time at Ichiban’s headquarters. Tupac collaborated with Ichiban’s MC Breed on the song “Gotta Get Mine.” Jessie-Wheeler recounted an intense experience with Tupac, revealing the multifaceted nature of the artists who collaborated with Ichiban.

“He came in, and he wasn’t happy,” she said. He started slamming stuff off the desk. He’s mad. ‘I want this. I want that.’ He got himself together and left. We talked later that night, and he was just like, ‘You know, I’m really not like that.’ And he wasn’t. He was such a good person when you really had an opportunity to sit down and talk to him.”

Ichiban’s lobby wasn’t the only place filled with VIPs—the label’s phone lines also had their fair share of people calling trying to work with Ichiban.

“I got a call one day from O’Shea Jackson,” said Jessie-Wheeler. “Okay, me being 24, he’s talking, and I’m like, ‘okay’… Not having a clue. And then he goes, ‘Well, it’s me, Ice Cube.’ And I’m like, ‘yeah, right.’ Literally, on the phone, I said to him, ‘Yeah, right. Prove it.’ And he did something. I was so embarrassed.”

There were many reasons so many famous faces chose Ichiban. The biggest reason was that Ichiban was a one-stop shop.

“We were full-service,” said Jessie-Wheeler. “Not only did we have our in-house radio promotions team, but we had marketing, an art department — everything that a major label could give you.” However, the label’s independent status meant operating with fewer resources than its major counterparts. “The marketing dollars would be a little smaller,” Jessie-Wheeler said. “And you know what? You had to do some of the work yourself.”

Another difference between Ichiban and other labels was accessibility.

“I think what set Ichiban apart in managing and dealing with artists still goes back to that family environment,” said Jessie-Wheeler. “You couldn’t just walk into Warner Brothers or Jive Records and expect to see Clive Davis, but at Ichiban, you could walk in and say, ‘Hey, I need to see John’ or ‘I need to see Shonda.’ There was such open access. You could immediately talk to Urban Radio or marketing about any issues.”

A major aspect of the Ichiban approach was the personalized support the label provided to artists, especially during tours. Abbey said this was a critical difference between the Ichiban model and major labels: “Majors tell you they’re gonna do it, and you show up in Peoria, and nobody even knows you’re home.”

In contrast, at Ichiban, Abbey said, “People like Vince would make sure everybody in Peoria knew you.” This approach was also a rarity in the independent label scene and set Ichiban apart from its contemporaries such as MALACO.

Ichiban was also committed to creating opportunities for well-known artists who couldn’t move units, as well as those new to the music industry. “We had a lot of Black acts that didn’t sell that well. That was my goodwill. There were Black acts that couldn’t get a record deal. They were low-budget. So, it’s like, let’s do it,” Abbey said.

Abbey described Ichiban’s operational model as akin to a conveyor belt system in a Chinese restaurant, where each artist’s work was systematically promoted. “We will put your music on the trolley, and it will go through the system. Hopefully it will work,” he said.

DJ Easy Lee highlighted the label’s willingness to take risks on lesser-known artists. “It was just another numbers thing for John. If something hit it off, it hit,” said DJ Easy Lee.

For DJ Easy Lee’s Wrap Records, several songs “hit off,” including 3 Grand’s “Daisy Dukes” and 95 South’s “Whoot There It Is,” which went platinum.

"Whoot There It Is"

95 South

If a new release showed potential, Ichiban would consider investing more resources.

“If we press 5,000 pieces and Vince Hart sent it out on the retail side as feelers and we sent it to the mix jock shows and just see what they are biting on, then that would determine if Ichiban wanted to spend some more money,” DJ Easy Lee said of the process.

Abbey also touched upon the balance Ichiban sought between offering the benefits of a label while allowing artists a level of independence, especially in creative terms.

“We probably released more than 100 CDs that were by individuals that didn’t want to be part of a label, but they wanted the benefits of a label. Whereas, if you were on Ichiban, like every other label, we basically controlled what you recorded. Not as much because I think we were always a creative force that stumbled into the business rather than the business that stumbled into the creative force.”

As far as finances go, Jessie-Wheeler offered insights into the financial agreements at Ichiban, suggesting they were more than fair, especially compared to major labels.

“If you took a contract for an artist from like a Warner Brothers or Jive Records at that time and compared it to what Ichiban offered,” she said, “You would see vast differences in what you could actually make and take home.” She also touched upon the evolving nature of record deals, noting the shift towards 360 deals in the industry, where labels take a cut from all artist revenue streams.

Jessie-Wheeler further explained how advances and royalties worked at Ichiban compared to major labels. At Ichiban, artists might receive less upfront money but stood a better chance of taking home significant earnings.

“A lot of our deals, specifically in reference to distribution, were 70-30,” she noted, indicating that the label made 70%, with the remainder going to the artist. This structure was particularly beneficial for successful artists such as MC Breed, who could “write his own check” due to his consistent sales.

Ichiban’s approach to artist funding was measured and sustainable. “We would cover your recording costs. We would do marketing, but the value of that was, when you start making money, it’s your money,” Jessie-Wheeler said. This model allowed artists to earn more consistently over time, avoiding the trap of massive advances that needed to be paid back before seeing any profit.

DJ Smurf, reflecting on his experience with Ichiban, highlighted the label’s refreshing perspective on success.

“We didn’t have to sell 2 million records,” he said. This approach allowed artists to celebrate achievements that would be deemed modest by major label standards. Selling 30,000 copies of an album with Ichiban was celebrated just as much as a 1 million-copy milestone. This mindset provided a much-needed reprieve from the high-pressure environment of major labels, where an artist’s success often hinged on massive sales figures.

Unlike many labels where contractual obligations often bound artists, Ichiban operated on a principle of mutual benefit and understanding. “If we’re not doing well for you or you think you can go somewhere else and do well, then we wish you all the best,” Jessie-Wheeler said. This level of flexibility was rare in the industry and further emphasized Ichiban’s commitment to the welfare and success of its artists.

Next: 4 The Next Episode

By 1995, Ichiban Records had grown into a “mini-major,” releasing 75 to 100 albums annually across diverse genres. Despite its success, a troubled partnership with EMI caused financial struggles. Attempts to secure funding failed, and by 1999, Ichiban was forced to close.