6/7 Then and Now

The Color-Line: Democracy and the Past

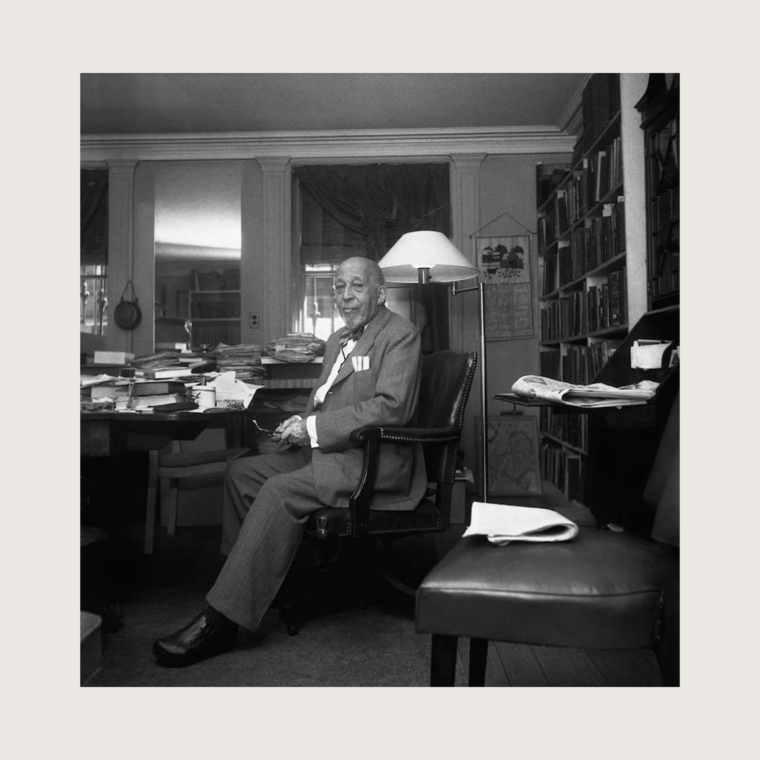

In Atlanta, educator and social activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrote some of his best-known works, including The Souls of Black Folk, published in 1903. Seven years earlier, he had accepted a faculty position at Atlanta University to establish a sociology program.

During his nearly 13 years in Atlanta, he wrote extensively on issues of racial discrimination and the realities of life for Black Georgia residents. Du Bois returned to Atlanta University in 1934 and for a decade wrote of the social and political conditions—as well as the contributions to democracy—of African Americans in the South.

Decades later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, far reaching in their scope and impact, were important milestones in securing the rights of African American citizens and improving the state of democracy in the United States.

Both were achieved in large measure by the determined efforts of student activists, including those of the Atlanta Student Movement.

They did not, however, achieve the end of the color line.

Header Image: Martin Luther King Jr. casts his ballot in Atlanta in 1964, while his wife, Coretta Scott King. Bettman /Getty

And here is a land where, in the higher walks of life, in all the higher striving for the good and noble and true, the color-line comes to separate natural friends and coworkers. … The white man, as well as the Negro, is bound and barred by the color-line, and many a scheme of friendliness and philanthropy, of broad-minded sympathy and generous fellowship between the two has dropped still-born because some busybody has forced the color-question to the front and brought the tremendous force of unwritten law against the innovators.

The Past is Always Present

In 1956, W.E.B. Du Bois, champion of Black political and civil rights, wrote that for the first time he would not cast a vote for president. Instead, he was discouraged that democracy had seemingly disappeared in the United States. No two parties existed, he said, instead there was but one party with two names – Republican and Democratic – “and it will be elected despite all I can do or say.”

Ironically, Du Bois’ growing disappointment in the democratic process coincided with the Civil Rights Movement and the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “Give us the ballot,” King said in a 1957 speech, “and we will no longer have to worry the federal government about our basic rights. Give us the ballot, and we will no longer plead to the federal government for passage of an anti-lynching law. We will by the power of our vote write the law on the statute books of the South and bring an end to the dastardly acts of the hooded perpetrators of violence.”

Du Bois died August 27, 1963, one day before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his speech, “I Have a Dream,” at the Lincoln Memorial as part of the March on Washington.

Within one year, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. This act was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965 signed by President Lyndon Johnson. It outlawed discriminatory voting practices adopted in many Southern states after the Civil War, including literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting.

History is Never Finished

Black voters and other people of color continue to face hurdles accessing the ballot box. Purging voter rolls, gerrymandering, and reducing the number of polling places and voting booths in Black and brown communities are barriers to the most critical part of the democratic process.

Following record voter turnout for the 2020 presidential and 2021 Senate runoff elections, Georgia voters of color played a leading role in sending the state’s first Jewish senator and first Black senator since Reconstruction to Washington.

In 2021, Georgia state legislators passed the Election Integrity Act, SB 202, which imposes greater restrictions that have a direct impact on the state’s low income, Black, and non-white voters.

As Jim Crow followed the progressive Reconstruction era, the potential impacts of SB 202 in restricting ballot drop box locations, limiting the use of mobile voting units, and placing conditions on no-excuse absentee voting. Many consider these limitations to be consistent with historic disenfranchisement practices used in the past to suppress Black voting.

Despite the SB 202 restrictions, more election day votes were cast in the 2022 runoff than on election day in the 2022 general election, on election day in the January 2021 runoff, or on the general election day in 2020. In addition, Georgia voters broke midterm records for early and absentee voting. In the end, Senator Raphael Warnock won reelection in the midterm runoff with more than 51% of the vote.