4/7 Students and Strategy

The Atlanta Student Movement

On February 1, 1960, four North Carolina A&T State University students entered a Woolworth department store, sat down at the lunch counter to be served, and changed the course of history. Their simple act of nonviolent, direct action launched a movement that helped end segregation and pave the way for civil rights legislation in 1964 and 1965.

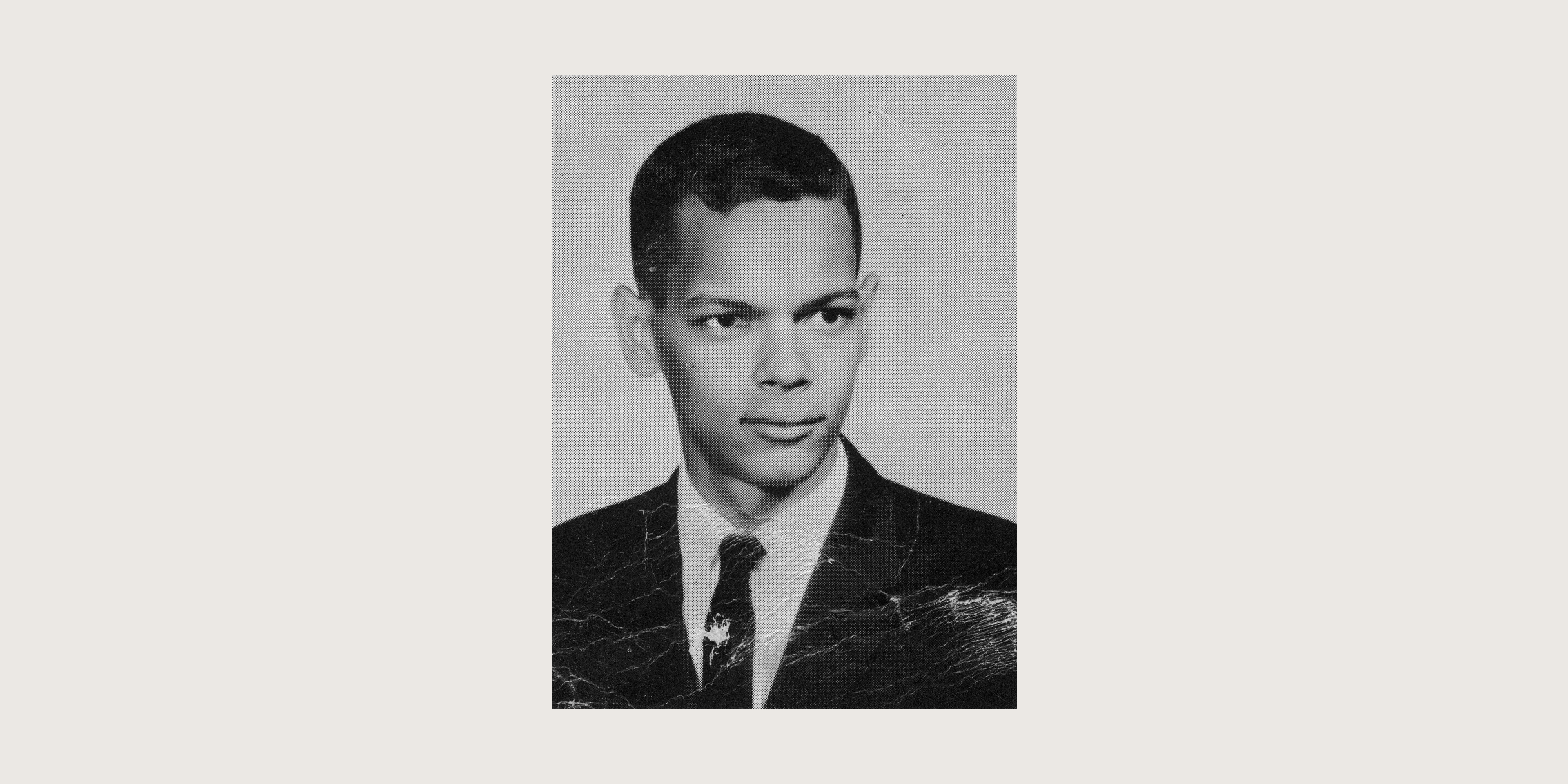

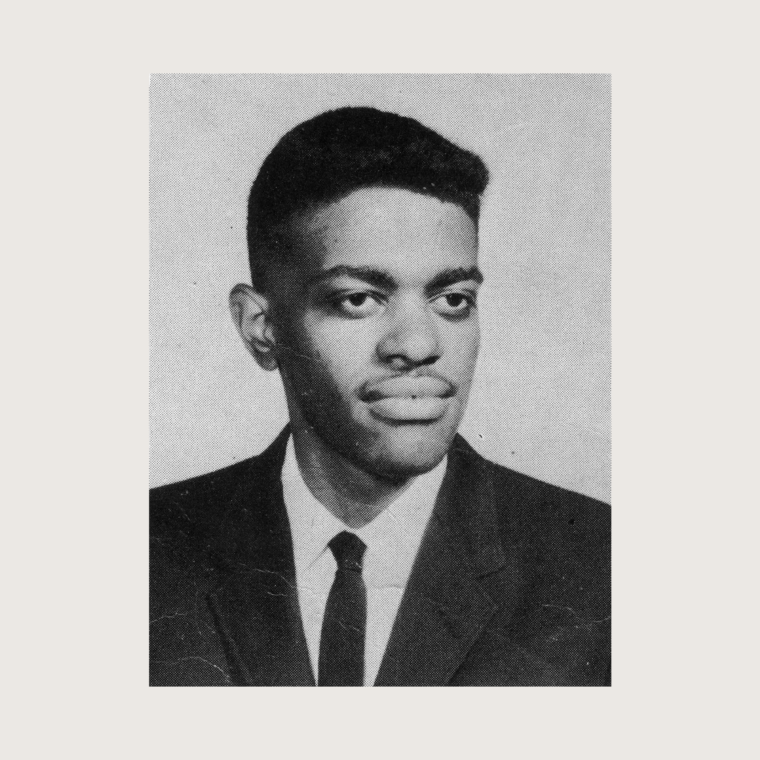

Lonnie C. King, a Morehouse College student, took note of the actions in Greensboro and convened students from the colleges and universities that comprised the Atlanta University Center (AUC): Atlanta University, Clark College, Morehouse College, Morris Brown College, Spelman College, and the four seminaries represented in the Interdenominational Theological Center.

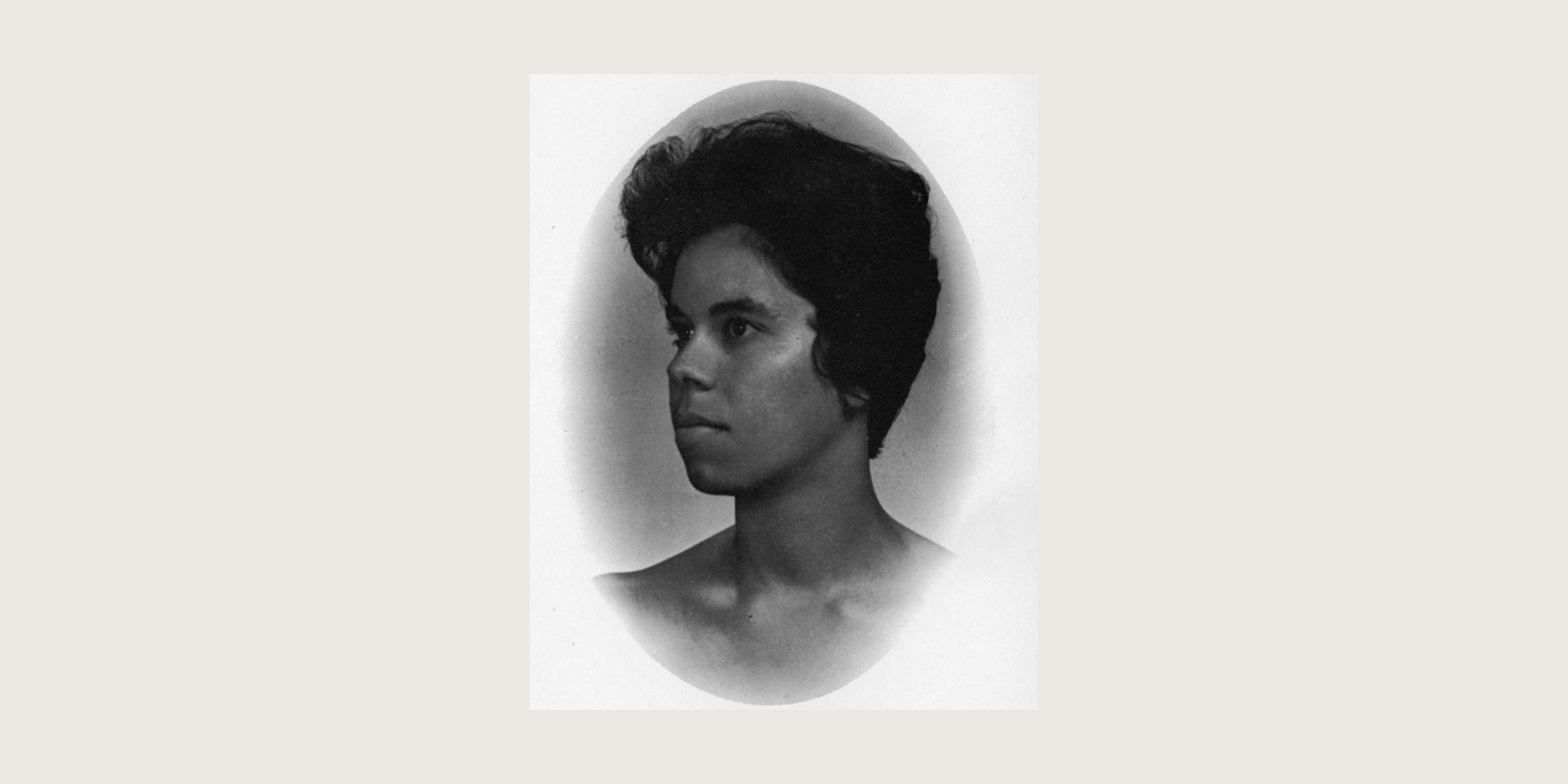

Nineteen students founded the Committee on the Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR). Hershelle Sullivan, a Spelman student, later joined Lonnie King as its co-chair in establishing what is now known as the Atlanta Student Movement.

Header Image: Spelman student Marion Wright and classmates study at the Fulton County jail during their incarceration for violating Georgia’s anti-trespassing law during a sit-in. Courtesy Getty Images

We, the students of the six affiliated institutions forming the Atlanta University Center – Clark, Morehouse, Morris Brown, and Spelman Colleges, Atlanta University, and the Interdenominational Theological Center—have joined our hearts, minds, and bodies in the cause of gaining those rights which are inherently ours as of the human race and as citizens these United States.

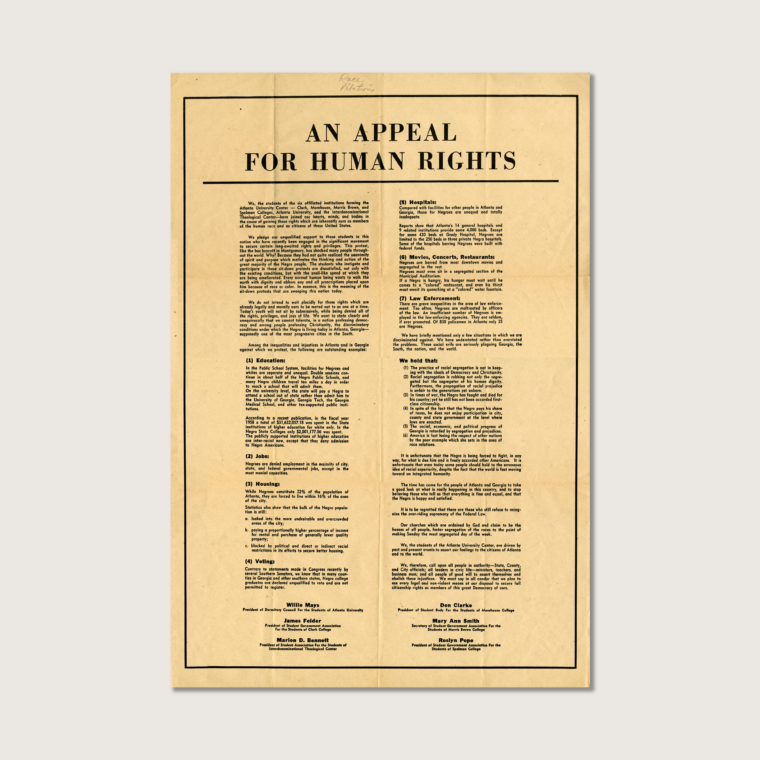

COAHR and “An Appeal for Human Rights”

On March 9, 1960, COAHR outlined their grievances in a paid advertisement titled “An Appeal for Human Rights” and published it in the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and Atlanta Daily World. It later appeared in the New York Times, elevating awareness of the students’ activism and struggle for change.

The “Appeal” addressed inequalities in seven sectors of life: education, jobs, housing, voting, hospitals, law enforcement, and access to public spaces, which included movie theaters, concert halls, and restaurants. It concluded by calling on government officials and civic leaders to abolish these inequalities.

The “Appeal” drew criticism from local whites and prompted Governor Samuel Ernest Vandiver to dismiss the document as “anti-American.”

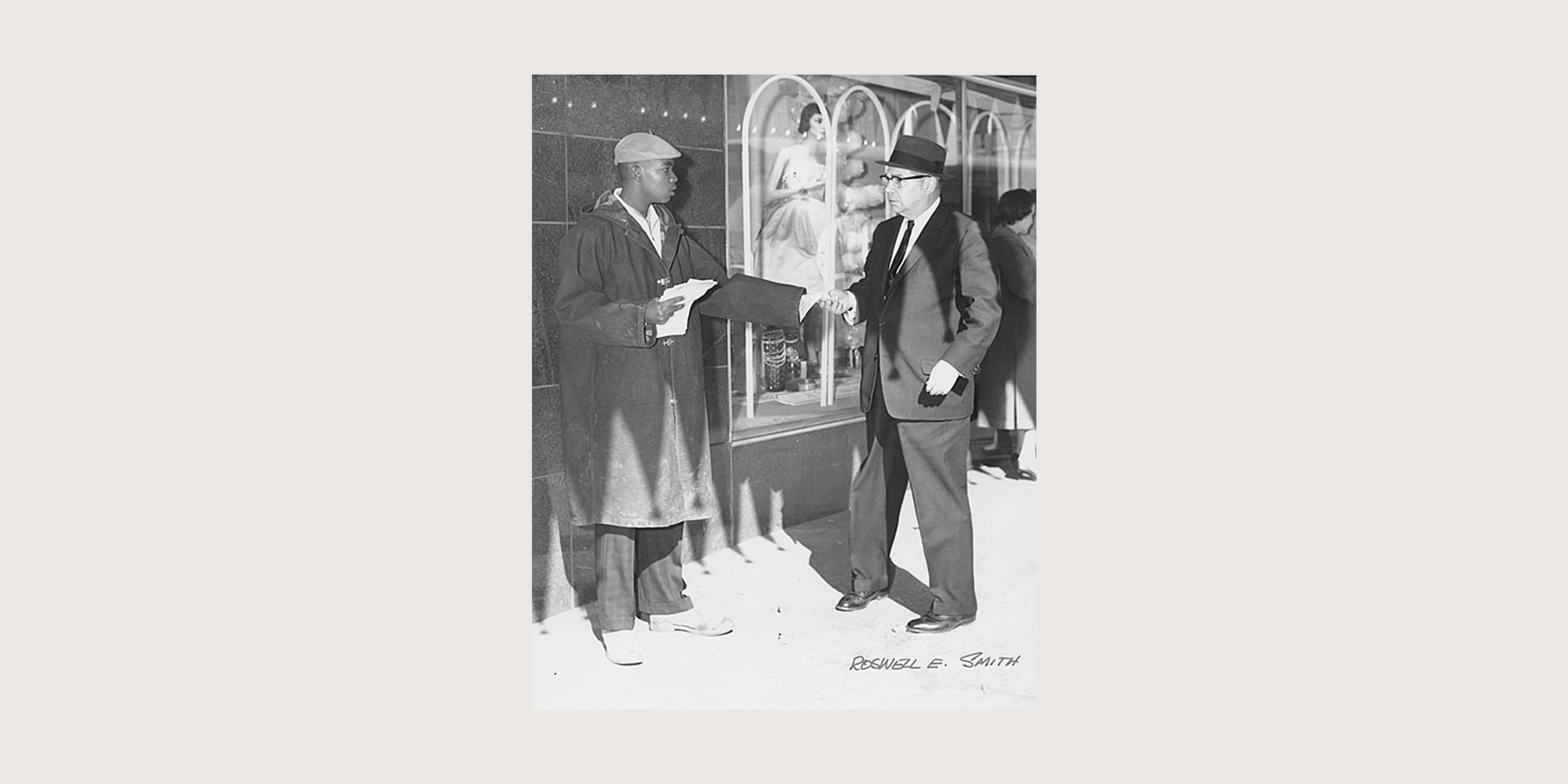

Sit-ins

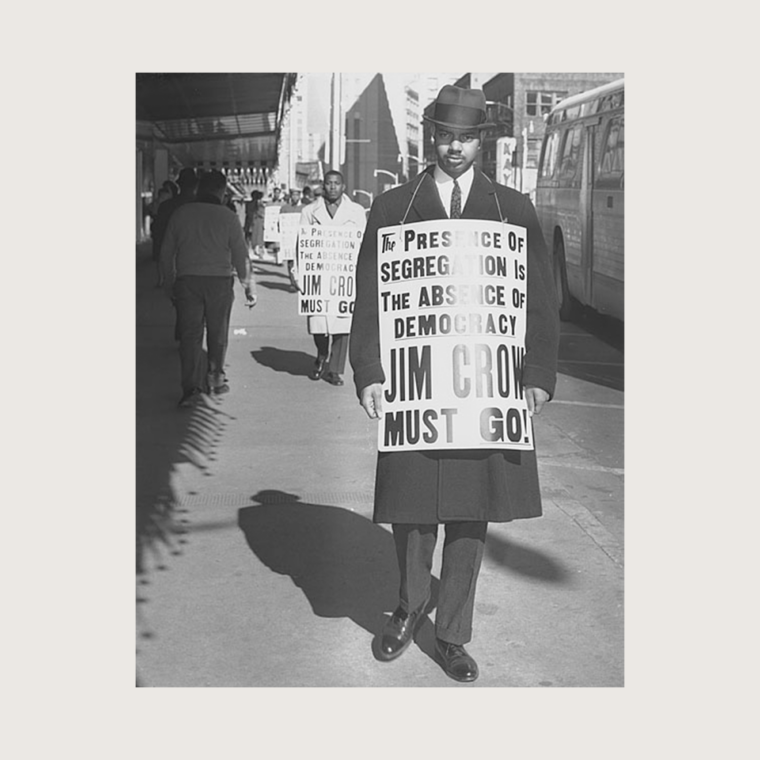

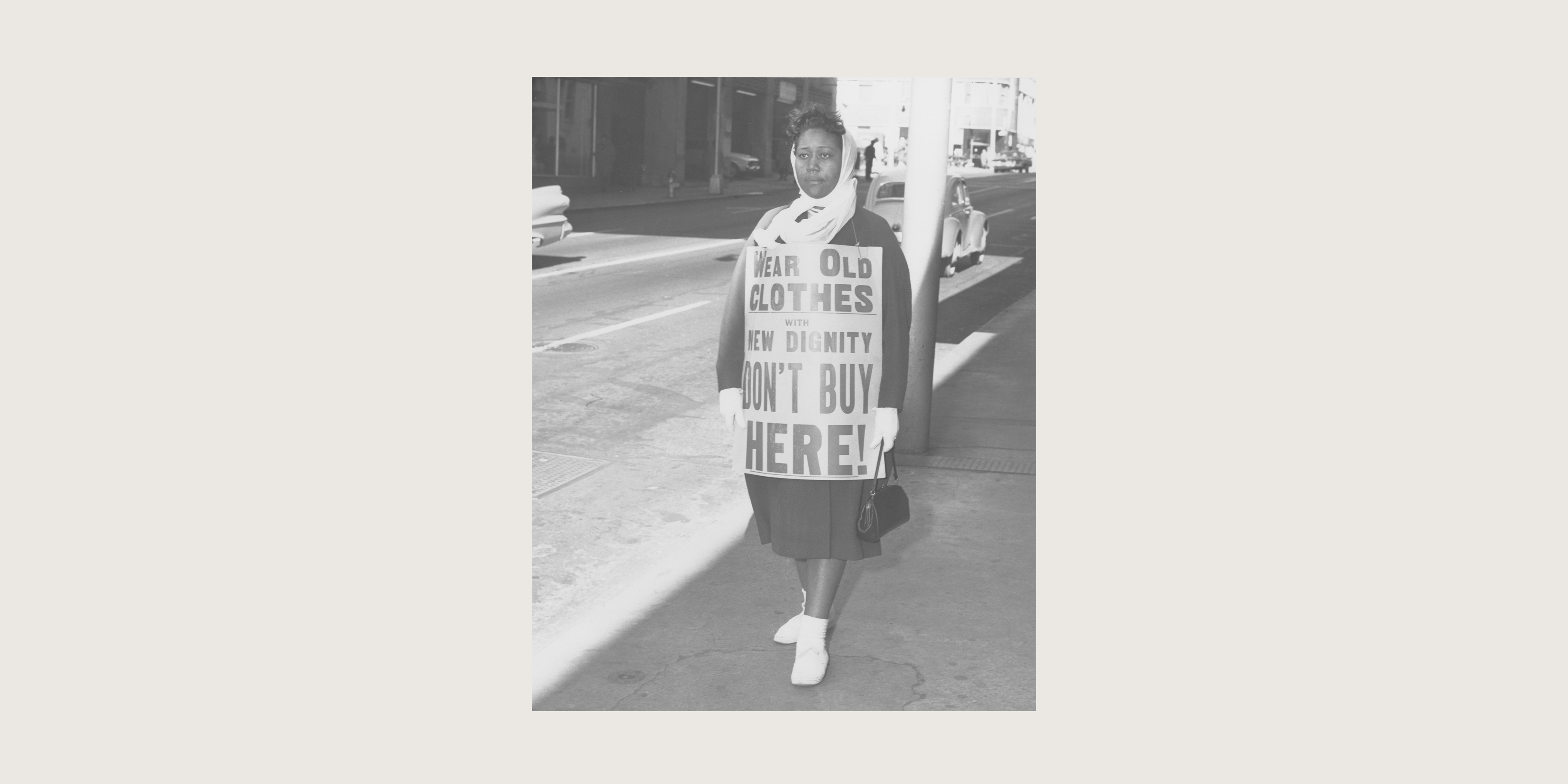

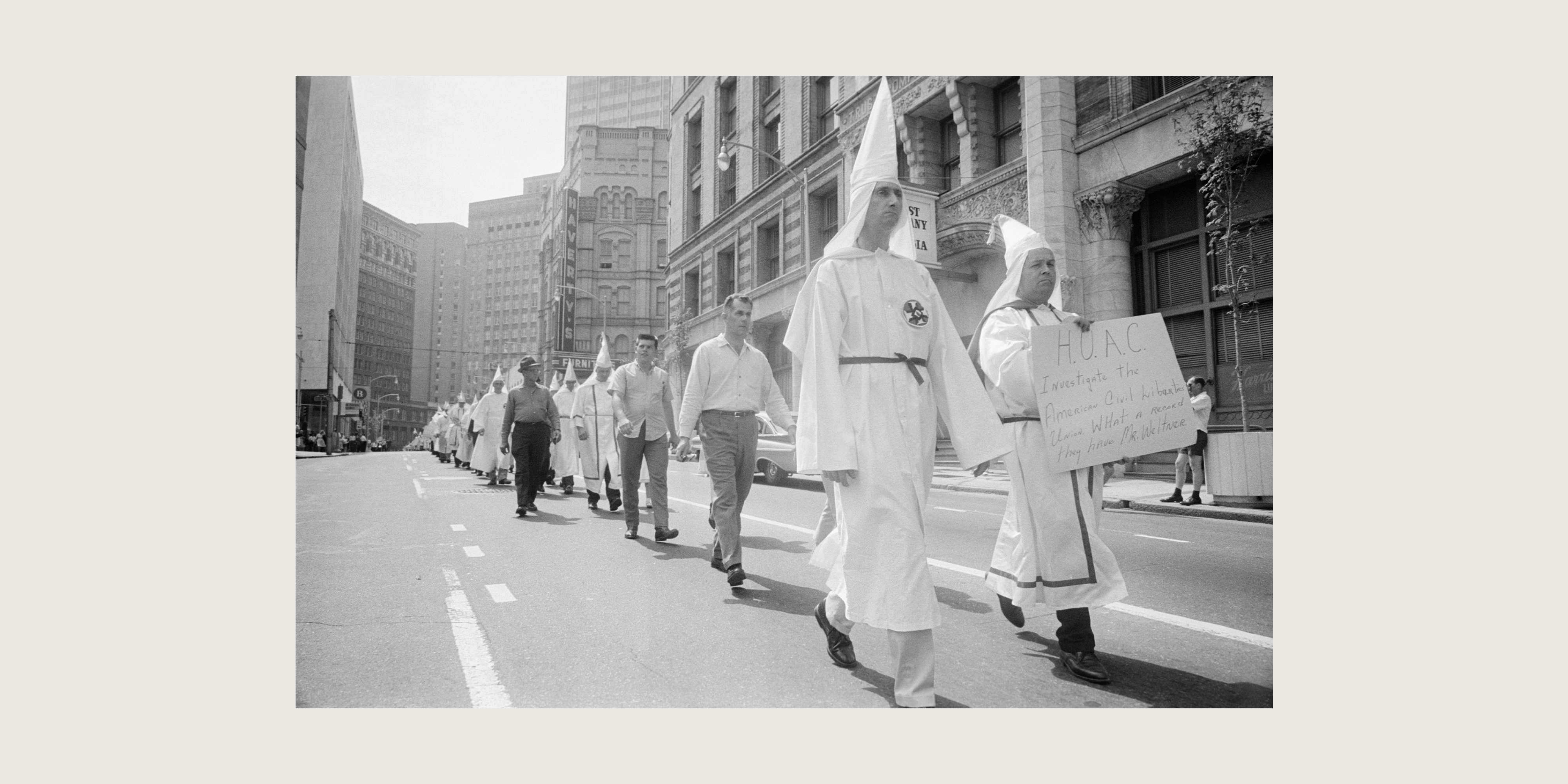

Six days after “Appeal” was published, students began orchestrating sit-ins at downtown Atlanta lunch counters and cafeterias, most notably at Rich’s department store, the largest department store chain in the South. Marches, picketing, and arrests of students, coupled with opposing demonstrations by the Ku Klux Klan, punctured the façade of Atlanta’s well-maintained image as “The City Too Busy to Hate.”

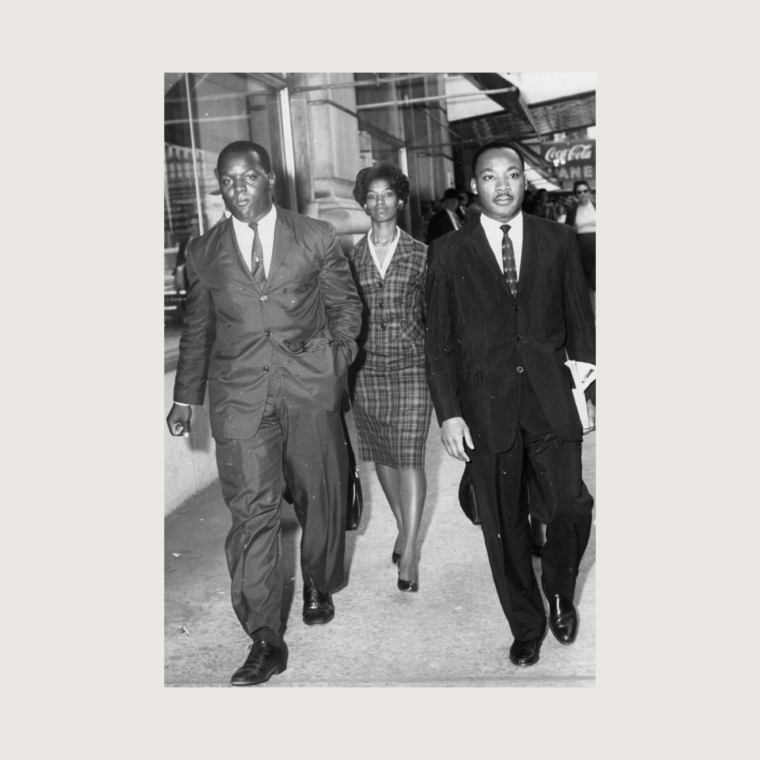

The efforts of Lonnie King, COAHR, and Atlanta University Center students garnered the support of most members of the Black community, including the presidents of the Atlanta University Center schools and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Though most of the white community was outraged or indifferent, some white students at Agnes Scott College, Georgia Tech, and Emory University became participants in the Atlanta Student Movement.

The student activities culminated in September 1961 when “four well-dressed Negro young women” desegregated the Magnolia Room at Rich’s.

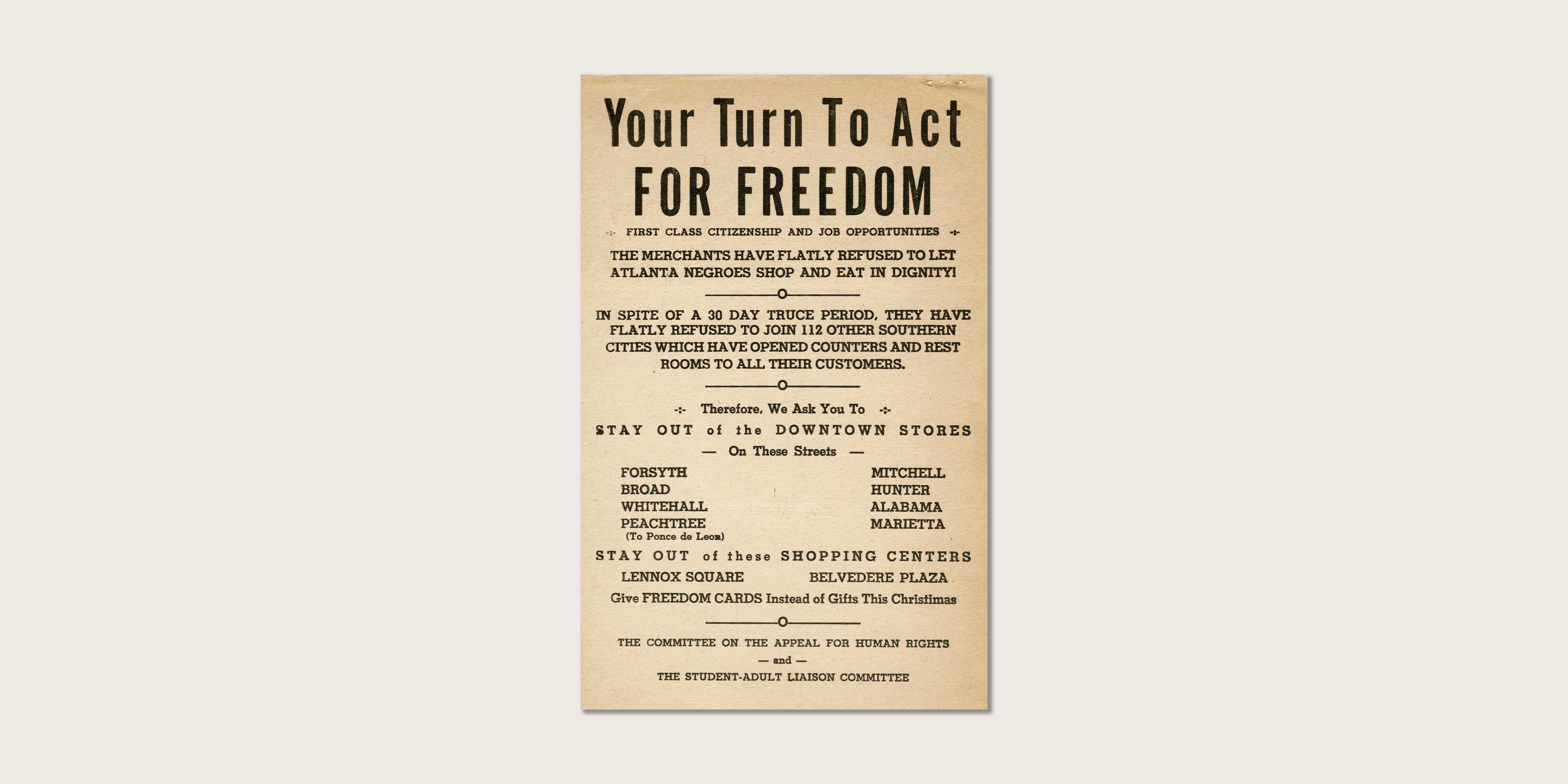

Continuing Protests

Despite the limited victory in September 1961, demonstrations for civil rights continued throughout the spring of 1962 and into that fall’s academic year. This led to negotiations between student leaders and white businessmen. As a result, in June 1963 they reached an informal agreement with dozens of restaurant owners to desegregate their facilities.

Nevertheless, students heightened their activities to push for complete desegregation of all public accommodations and advocated similar reforms in employment, education, health care, housing, and law enforcement.

Nonviolent Direct Action

Over the course of the next three years, participants in the student movement challenged segregation at several public buildings and facilities, including public parks and pools, Grady Memorial Hospital, and in restaurants and hotels.

Participants in the movement were active in voter registration and members of the Committee on Appeal for Human Rights helped with organizing protests in other Georgia cities, including Albany, Moultrie, and Savannah. The student-led coalition of Atlanta University Center students, Black business leaders and clergy, and white citizens was successful in forcing the hand of Atlanta’s white business and political leaders to end segregation in public facilities.

Many of these students continued to participate in the national Civil Rights Movement, culminating in the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In doing so, the members of the Atlanta Student Movement not only advanced their goal of social equality, but they also thrust the city of Atlanta and the South into the mainstream of American life.