1/7 A City Enslaved

A City Enslaved

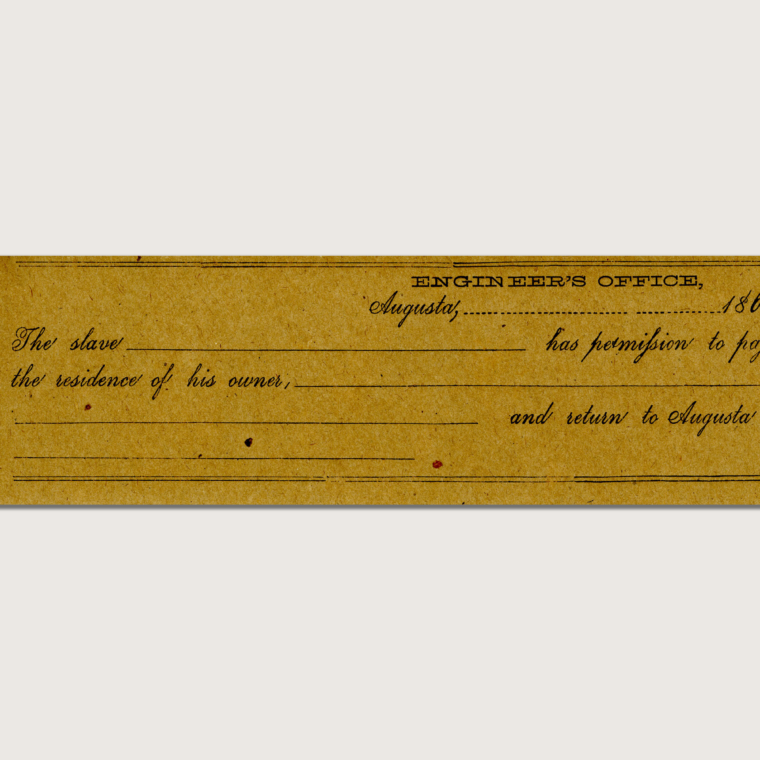

On the eve of the Civil War, Atlanta’s Black population was less than 2,000—which was still 20% of the total inhabitants. The overwhelming majority were enslaved. Scattered throughout the city, their movement and activities were tightly controlled.

A decade earlier in the summer of 1851, at least seven enslaved men were arrested for an attempted insurrection within the city. As a result, Atlanta City Council passed a wave of laws and restrictions on all Blacks in the city. The legal status of free Black persons—numbering perhaps 25 individuals—was only marginally above their enslaved brethren.

Heavily regulated, most Black individuals in Atlanta endured lifelong bondage, oppressive legal codes, and harsh racism. Despite the oppression of slavery, some Black residents conducted business, owned property, and founded churches.

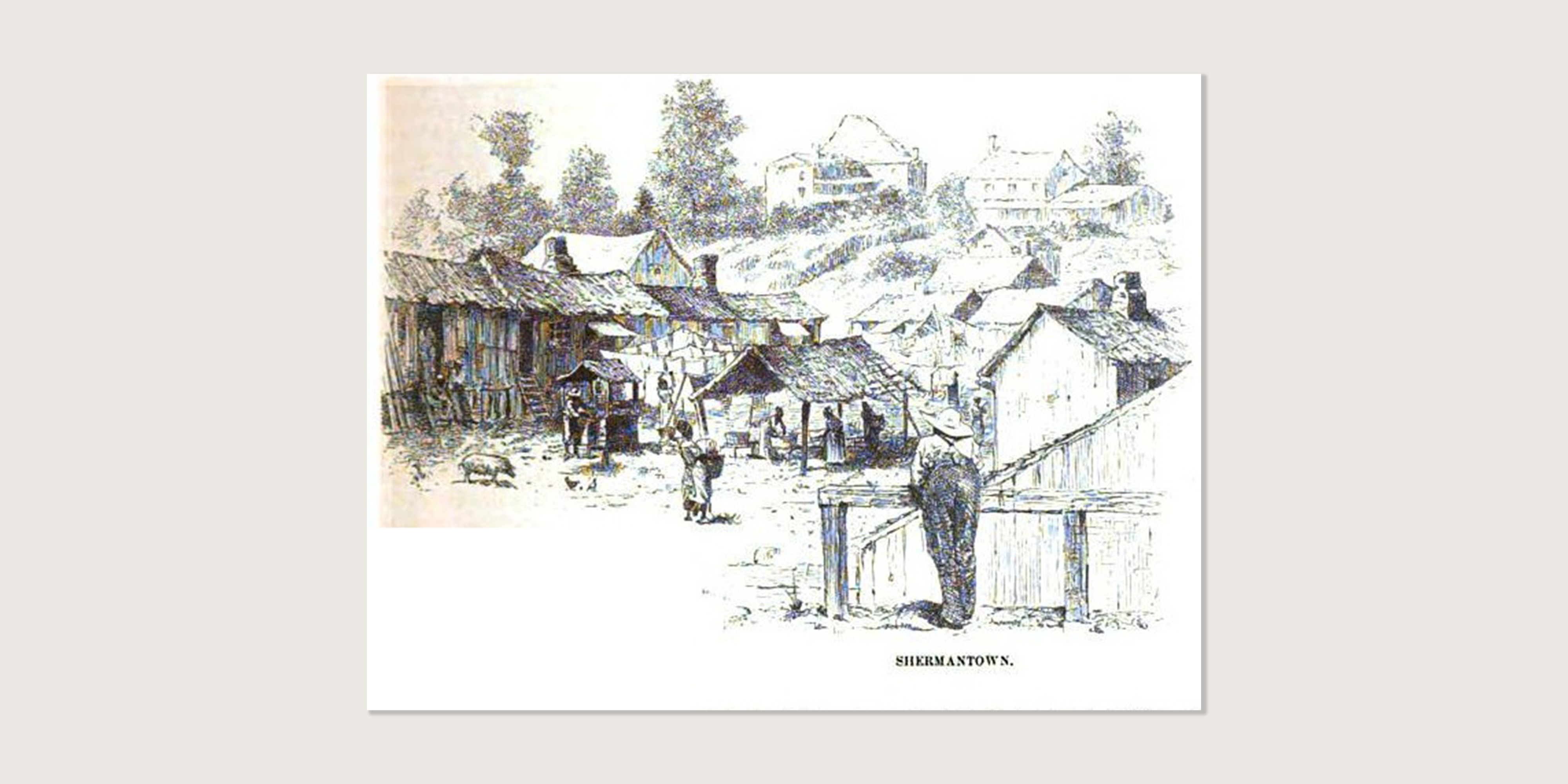

Atlanta faced a monumental undertaking to rebuild after the destruction of war. It became essential to establish a social, political, and economic system without the institution of slavery.

When freedom came at war’s end, Black residents in Atlanta established a community of their own institutions while fighting for personal independence and civil rights within those new systems.

Header Image: Escaped enslaved persons in Virginia, 1862. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Building a Black Community

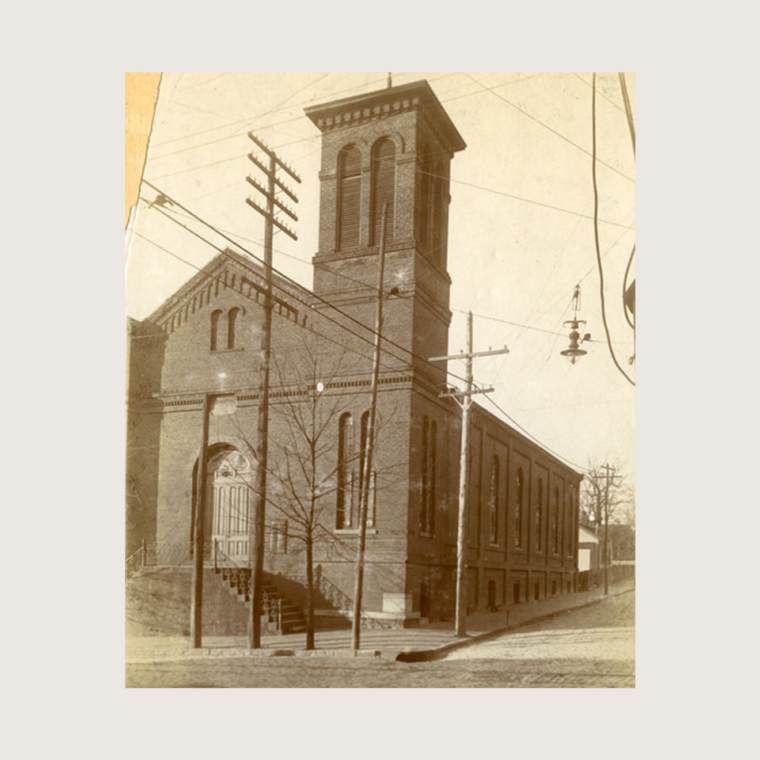

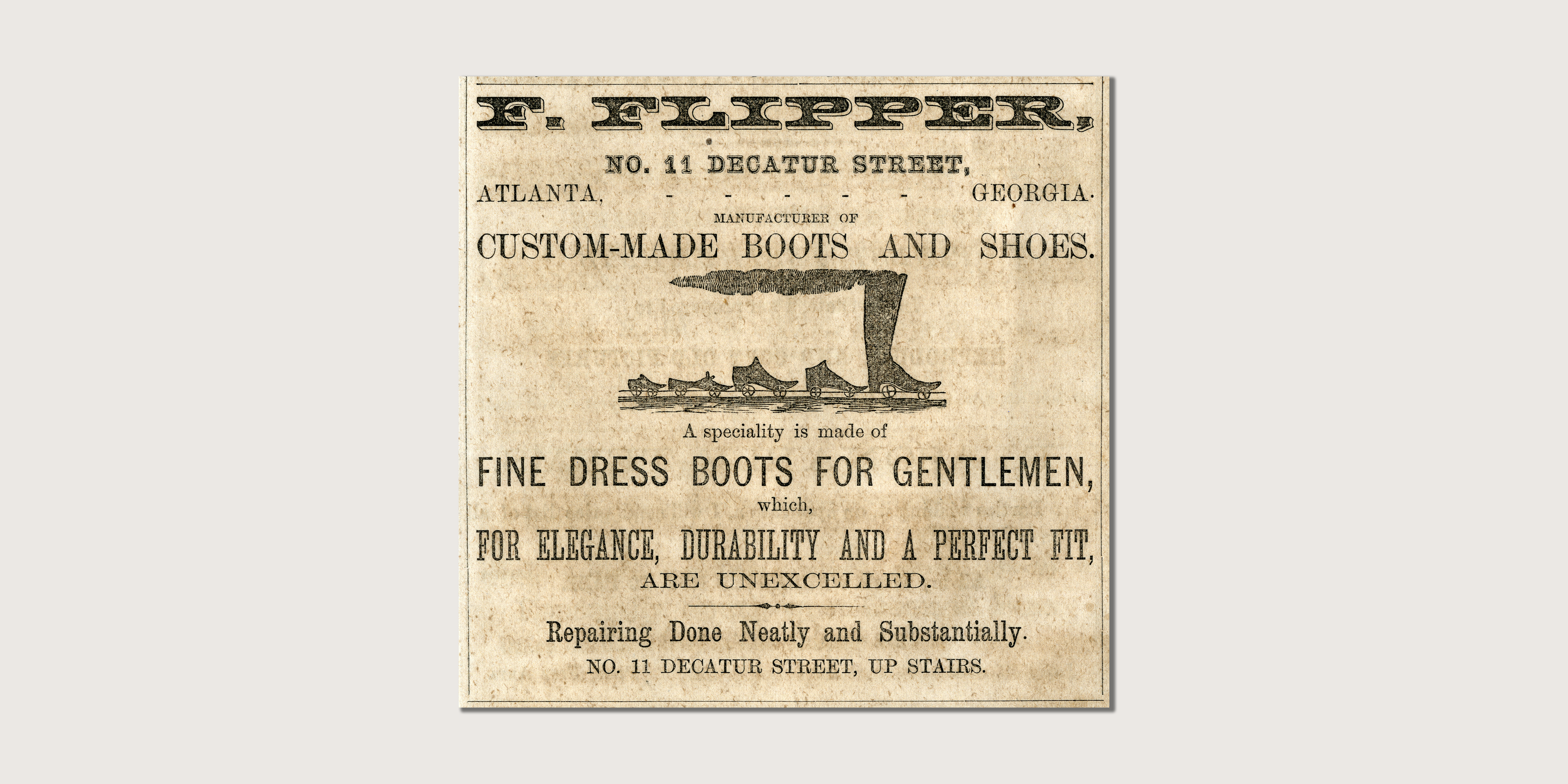

With freedom, the formerly enslaved population created economic opportunity, establishing businesses as grocers, blacksmiths, and shoemakers. Such entrepreneurship helped build Black communities. Other newly freed Black residents gained employment as cooks, waiters, and personal servants.

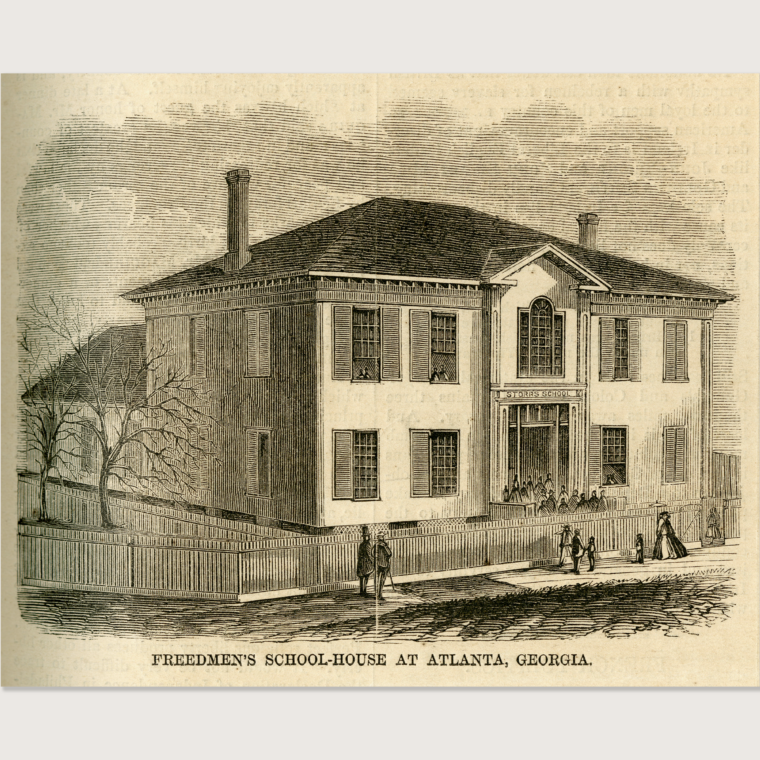

The Black community had a long history of educating themselves and their children during enslavement. Free Black residents in Savannah and Augusta had founded private academies in 1829. In Atlanta, two former slaves, James Tate and Grandison Daniels had already opened a school for the Black community when the American Missionary Society opened Storrs School in 1865 and Atlanta University in 1867.

Atlanta’s 1868 charter allowed African Americans the right to vote, and the city’s Black residents organized politically at the city and state level. The same year, 33 Black men were elected to Georgia’s General Assembly. Outraged by Black electoral success, white Democratic state legislators voted to expel the newly-elected lawmakers from state government. The expelled Black lawmakers and their white Republican allies petitioned the federal government for help. Federal officials forced the Democratic legislators to acknowledge the legitimacy of their Black colleagues, who were reinstated to the legislature. The limits placed on Democratic power in Georgia after the attempt to remove the “original 33” also meant that two Black Republicans, George Graham and William Finch, were able to seek and win election to Atlanta’s City Council in 1870. However, by 1871, Democrats had regained much of their lost legislative power, and they established city-wide elections in Atlanta, reducing the impact Black votes had within separate wards and negating the political power of Black voters.

These efforts were just the beginning of the work of white supremacists to implement a system of laws to exclude the Black public from the voting booth and the halls of government.