By Sophia Dodd

Editor’s note: Atlanta History Center is uncovering and sharing the histories of the descendants of Forsyth County’s Black residents who were expelled in 1912. If you are a descendant of the 1912 Forsyth County displacement, contact us at forsyth1912@atlantahistorycenter.com.

When Chuck Blackburn began planning a march to coincide with Martin Luther King Jr. Day in Forsyth County early in 1987, he believed he was celebrating one of the most important tenets of King’s life, brotherhood.

At the time, Martin Luther King Jr. Day was only being celebrated for the second time as a federal holiday in the United States and Forsyth County was entering its 75th year as a sundown county where residents used intimidation and occasionally force to prevent Black people from entering or living in the county.

In 1912, white residents of Forsyth County forced more than 1,000 Black residents from the area following the rape of local white resident Mae Crow. Crow, who later died from her injuries, never accused anyone of her rape, but white residents accused and arrested three Black men, Rob Edwards, Ernest Knox, and Oscar Daniel. A white mob lynched Edwards in downtown Cumming while the State of Georgia publicly executed Knox and Daniel after an all-white jury convicted them.

Amid the flurry of accusations and during a period of mob rule, white residents terrorized their Black neighbors. Due to the antagonism, Black residents left their homes, many taking only what they could carry, and fled the county.

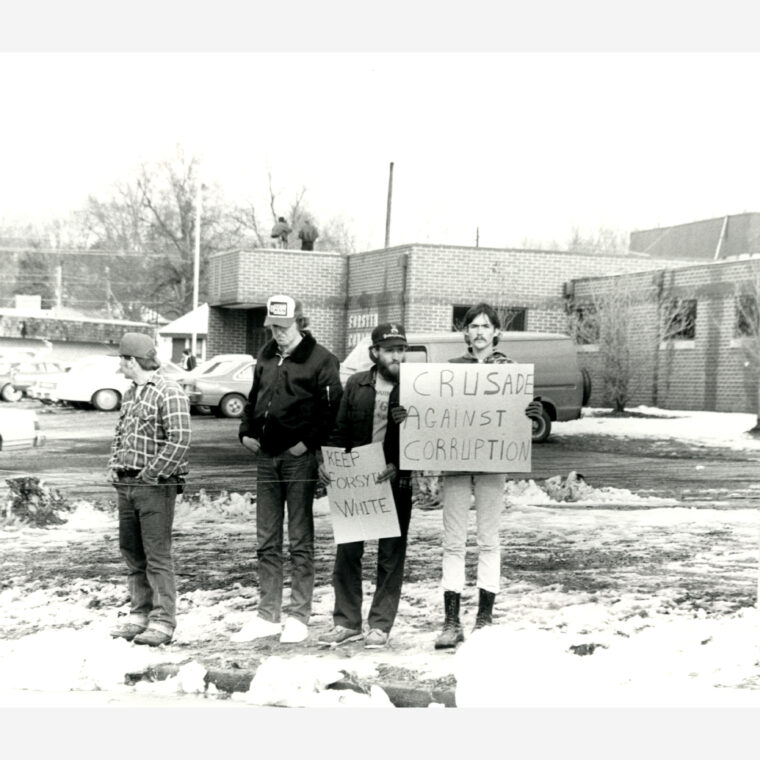

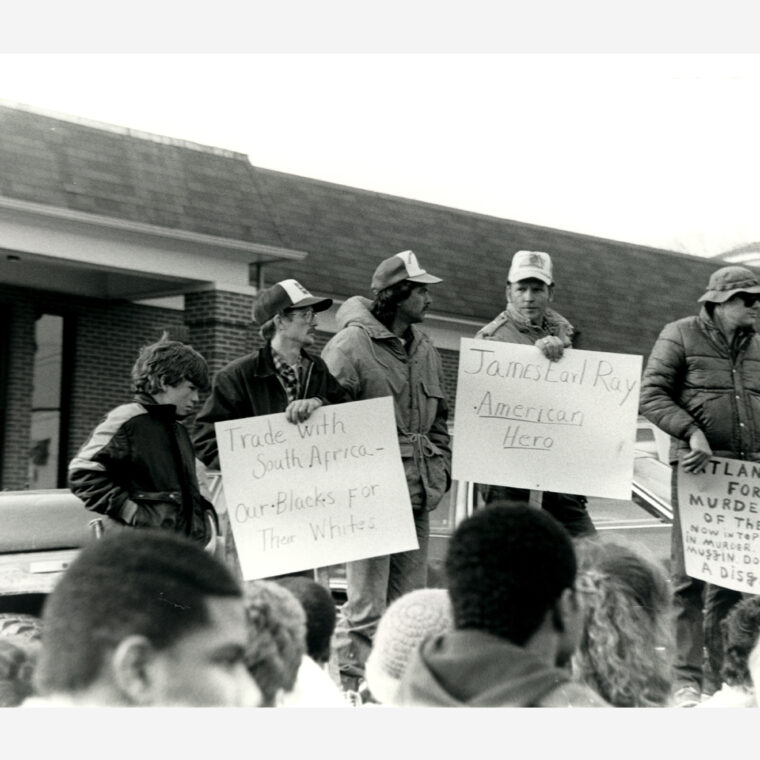

Counter-protesters gather in front of the Cumming Courthouse. Williams and other protestors originally planned to end the march in front of the courthouse before having to leave. Southline Press, Inc. Photographs, VIS.158.18.05, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Brotherhood Walk

To Blackburn, a “brotherhood walk” coinciding with King Day was the perfect opportunity to showcase a Forsyth County that wanted to move past racial violence and accept a more diverse community. Blackburn promoted the idea locally and wrote to several churches asking for support. Ultimately, no churches joined his efforts and Blackburn canceled the march after receiving threats of violence. Blackburn’s friend, Dean Carter, decided to carry on with the idea. Carter recruited civil rights activist Hosea Williams to the cause and renamed the event the “Brotherhood March.” Carter and Williams enlisted a group of about 75 individuals, Black and white, to march to the courthouse in downtown Cumming on January 17, 1987.

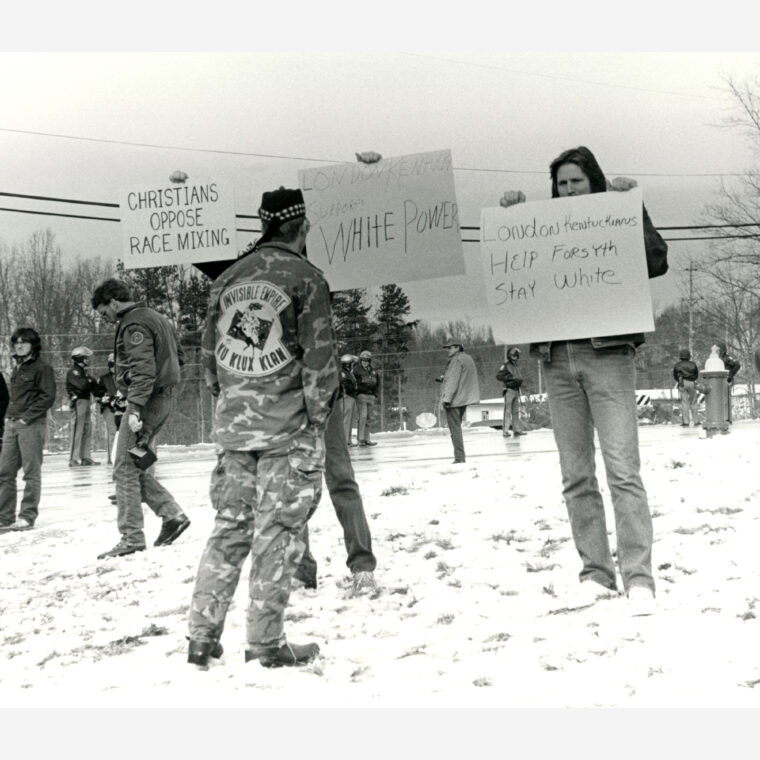

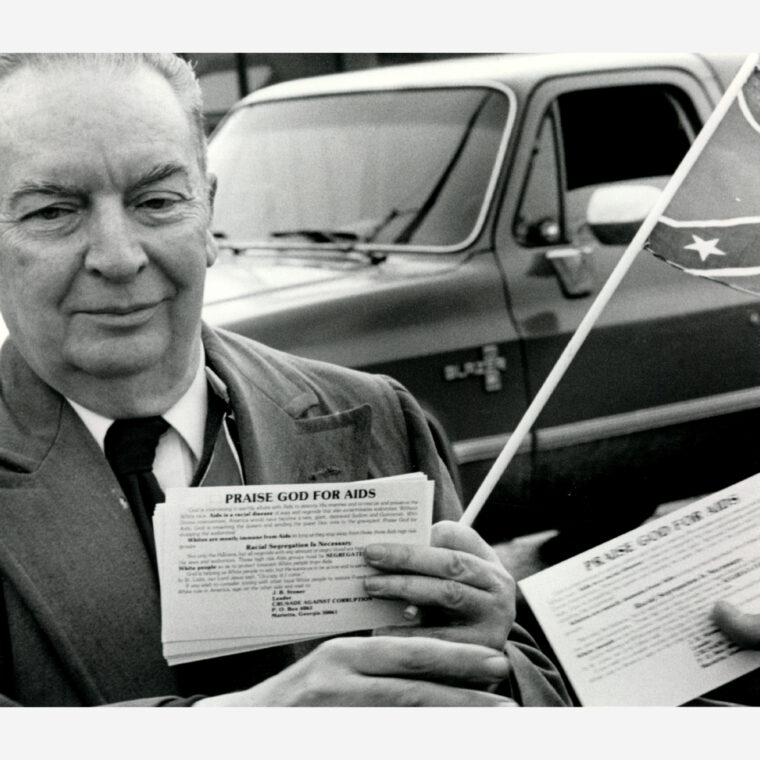

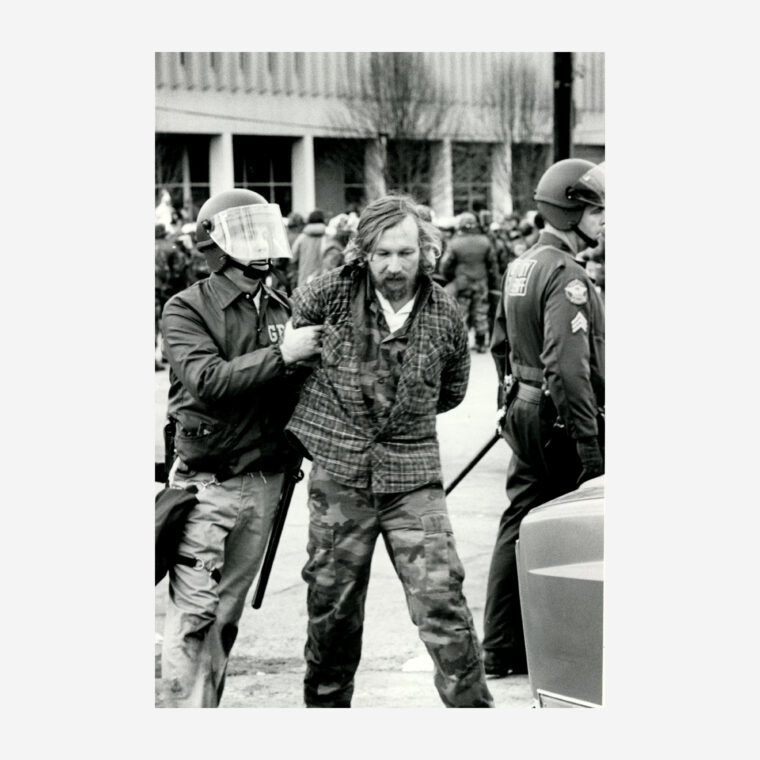

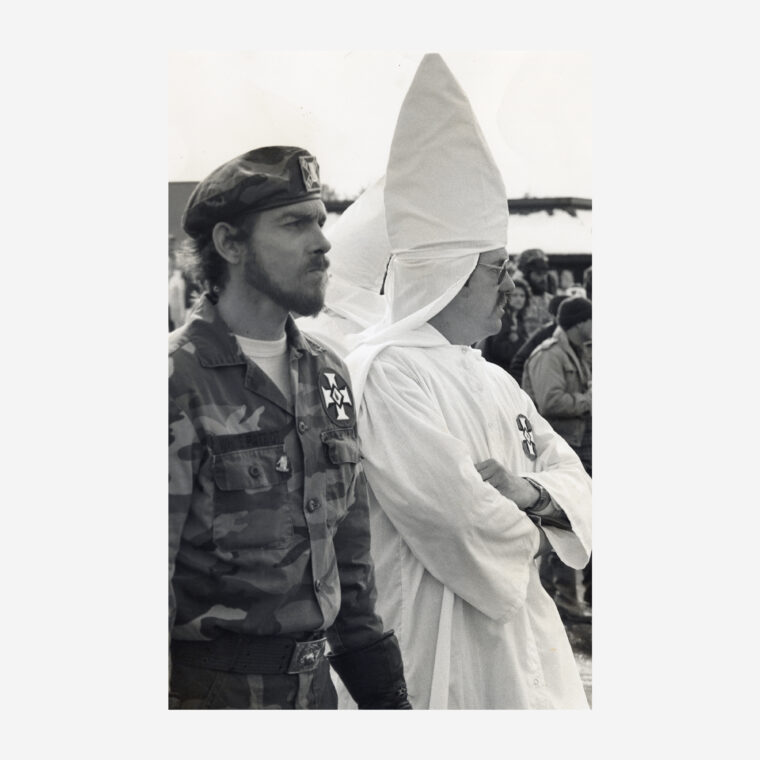

The march did not go as planned. For every protestor, there were more than five counter-protesters carrying Confederate flag regalia and white supremacist signage. Some even wore Ku Klux Klan robes. As many as 400 counter-protestors violently attacked marchers with rocks and debris as they attempted to pass through the streets. In the face of such fierce opposition, law enforcement informed Williams that they could not guarantee safe passage for the rest of the march, and Williams directed protestors to leave. They never made it to the downtown Cumming Courthouse as planned. The violence made national headlines and was a stark reminder of continuing issues of racism in the decades after King’s death. It also put a spotlight on the county’s history of mob violence such as the lynching of Rob Edwards and the forced expulsion of the county’s Black residents in 1912.

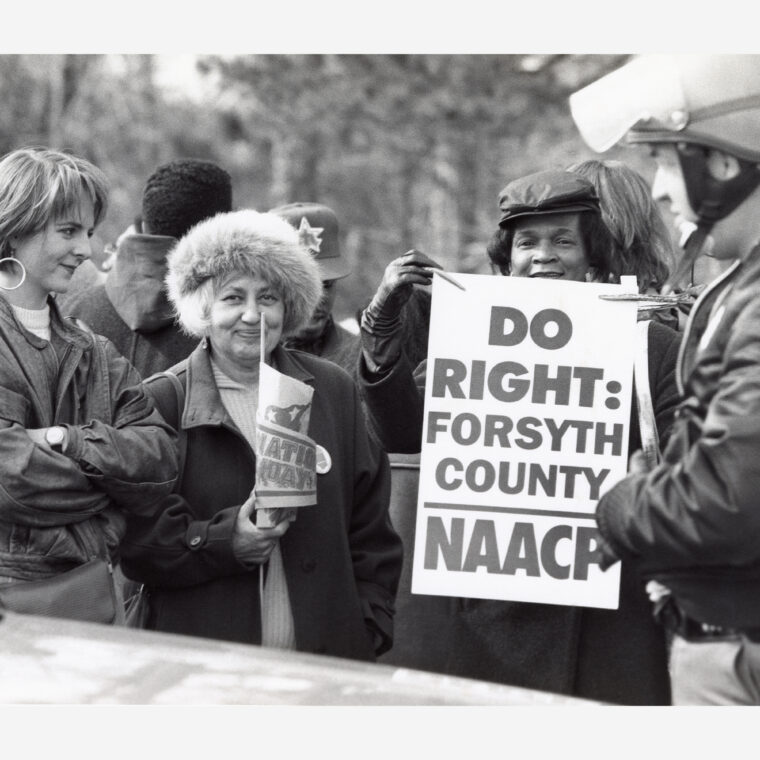

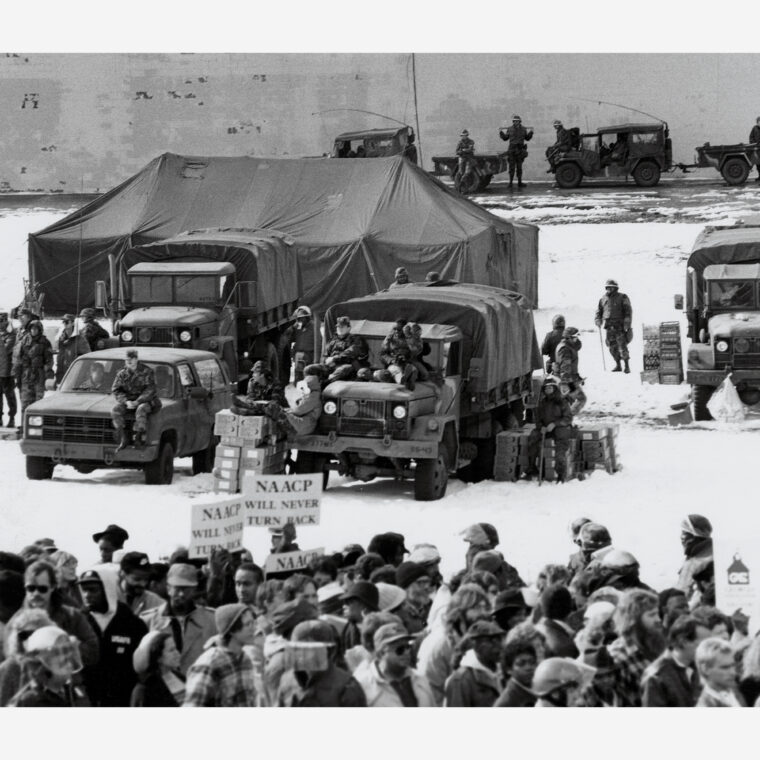

Following nationwide criticism of the violence, Hosea Williams planned a second march. The second Brotherhood March on January 24, 1987, was a success and marked an important moment in Forsyth County’s history.

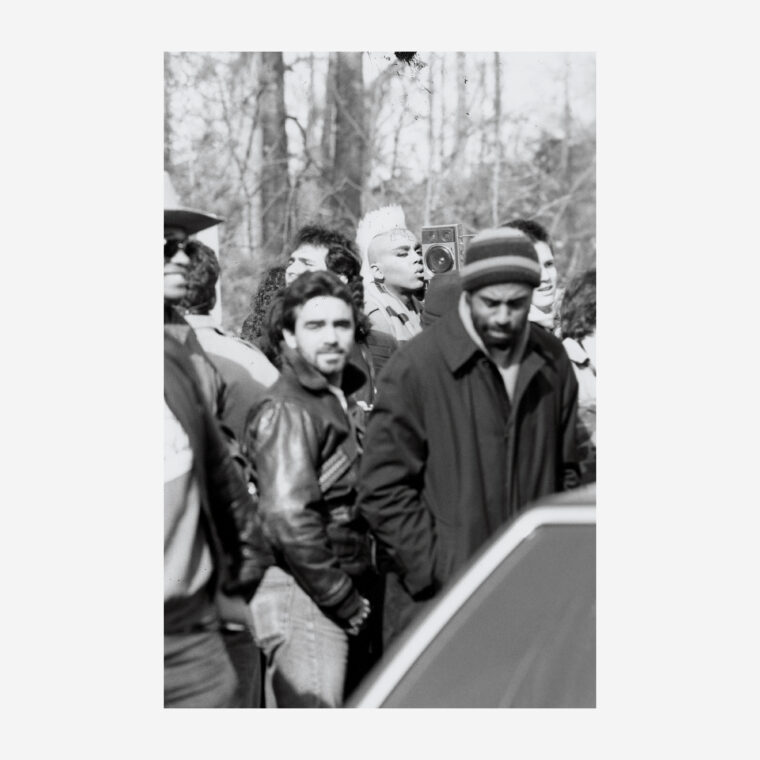

That time, about 20,000 people showed up to complete the march to the county courthouse in Cumming. Counter-protesters appeared again. But they were outnumbered by the diverse array of marchers challenging decades of racial violence and expulsion of African Americans. Hosea Williams returned in 1988 with 161 protestors for a third Brotherhood March with no issues.

While there has not been a Brotherhood March since 1988, the effect on demographics has been one of the most significant outcomes. No Black people lived in the county in 1980. By 1990, 14 Black individuals had moved to Forsyth, making up .03% of the population. Today, Black people make up almost 5% of the county population, a steady increase since 1990. In addition, Latinx individuals make up nearly 10%. The most significant increase in minority groups, however, has been with the Asian population. Though only .2% of the county in 1990, the Asian population today represents 17.9% of the county population.

The 1987 spotlight on Forsyth County forced a racial reckoning that has since opened the door for Black people and other minority groups to call Forsyth County home in the 21st century.

Related Content. Learn More.

-

Story

In September 1906, a white mob brutalized and terrorized Atlanta’s Black residents, resulting in the deaths of 25 Black Atlantans, the wounding of hundreds of Blacks, and the destruction of many Black businesses and homes. This period of racial violence has been passed down in history as a race “riot,” but “massacre” may be a more apt term.

-

Story

Like many professional Black Atlantans of yesteryear, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spent a lot of time at the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia. Because of his close relationship with the MWPHGLG, some have speculated that King joined the lodge and became a Prince Hall Freemason before his death.

-

Story

Visitors from across the Unites States travel to Atlanta, King’s hometown, to honor the legacy of his work. We invite you to look back at how we arrived at this moment in history.

-

Exhibition

Drawn from the collections of Kenan Research Center, the photography in this exhibition reflects the rich stories of Atlanta’s historically black colleges and universities, the Civil Rights Movement, and those of African American educators, entertainers, and athletes.