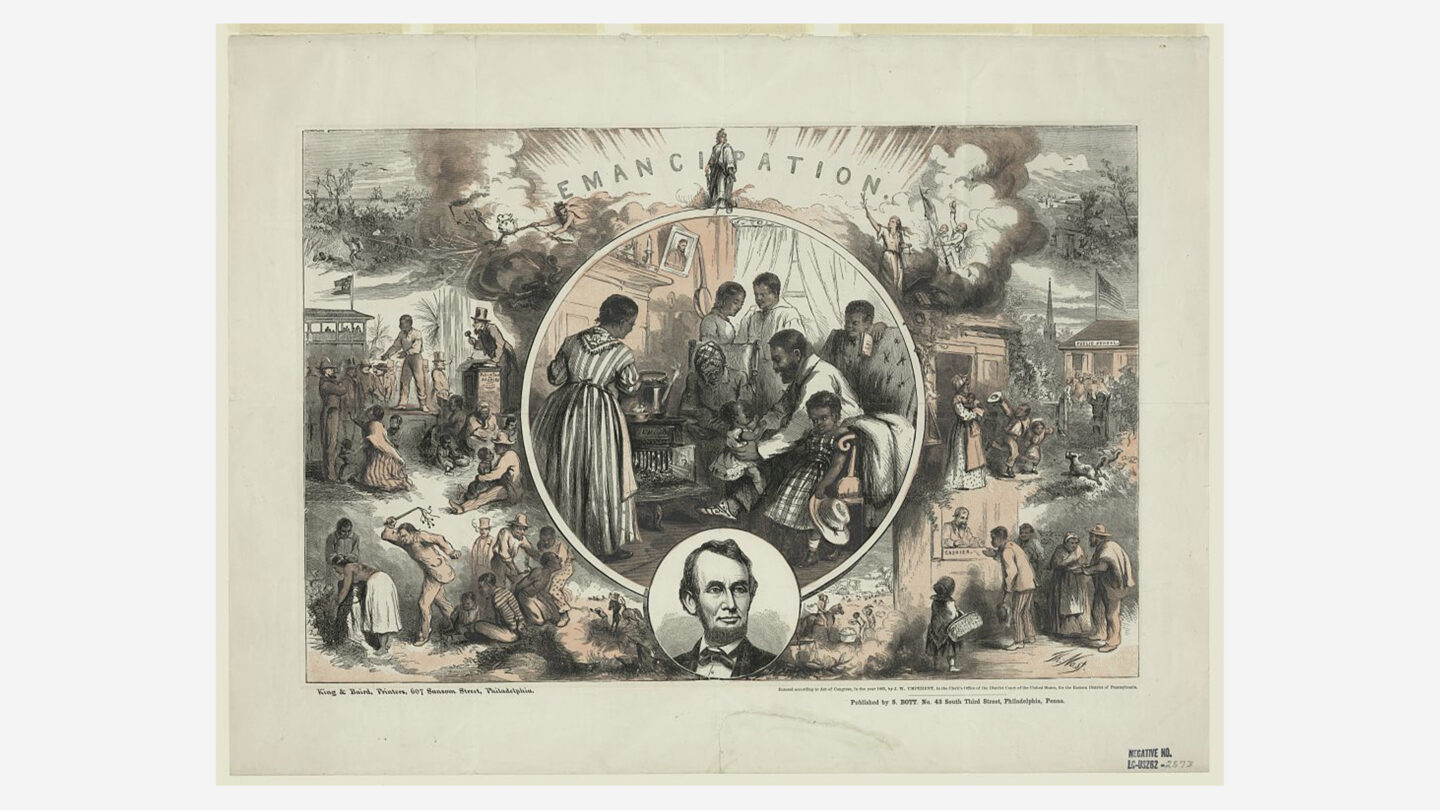

“The Emancipation of the Negroes, January, 1863 – The Past and the Future” (Thomas Nast, artist, King & Baird, engraver, from Harper’s Weekly, vol. 7, no. 317 (1863 January 24), pp. 56-57. Philadelphia: S. Bott, publisher, 1865; Library of Congress)

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in the middle of the Civil War, ending slavery for those in Confederate-aligned slave-holding states and territories. Though the decree was released on January 1, 1863, news of freedom reached those held in bondage throughout the Confederate States at different times.

The last group of people enslaved in Confederate strongholds to learn that they were free, as far as the U.S. government was concerned, were those in Texas. Blacks in Texas learned they were free when the U.S. Army occupied Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, two and a half years after Lincoln’s original declaration. Though the news was severely delayed, freedom for those who had been enslaved meant the hope of opportunity and the potential for a brighter future. These are some of the stories of the formerly enslaved and their lives after slavery.

Thomas Sims (1828–1902)

“Thomas Sims, The Slave” (John H. Manning, artist, Worcester & Pierce, engraver, from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, Boston: Frederick Gleason, publisher, 1851; Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections)

During his 74 years on earth, Thomas Sims saw many things. He saw a war divide a nation, chattel slavery come to an end, the aftermath of that war, and glimmers of what could be. When he died, he lived in Washington, D.C., an area that just 12 years prior had been a hub for the domestic slave trade.

Sims’s journey to the nation’s capital began in Georgia. He was born in 1828 to James Sims and Minda Campbell. Their enslaver was James Potter, an Irish immigrant who owned Colerain plantation, a 2,000-acre rice plantation on the Savannah River.

Map showing the location of Colerain Plantation (Savannah River Plantations, Savannah Writers’ Project, Mary Granger, editor, Savannah: Georgia Historical Society, publisher, 1947)

Potter allowed Sims to work in Savannah as a bricklayer and start a family with a free Black woman. Sims was 23 when he made his first attempt at freedom. He stowed away on the M & J.C. Gilmore, a steamship headed for Boston. Just before the ship was due to dock in Boston, Sims was discovered. Sims told the ship’s crew that he was a free Black man from Florida. The ship’s captain didn’t believe Sims’ story and locked him up in a cabin on board the vessel, possibly intending to alert authorities and receive a reward. Sims escaped from the ship and openly lived at a boarding house for Black seamen in Boston.

An account of Thomas Sims’ arrest in Boston. (Boston Evening Transcript, April 4, 1851, Newspapers.com)

When Sims sent a telegraph to his wife in Savannah asking for money, Potter learned Sims’ whereabouts. Potter sent his lawyer to Boston to retrieve Sims under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Officials tried to arrest Sims on April 3, 1851. Newspaper reports from the time say that Sims fought his would-be captors, stabbing one in the groin before being apprehended and imprisoned.

After a highly publicized trial, where abolitionist lawyers fought for Sims’ release and noted philosophers, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau argued for his liberty, the court found Sims to be a fugitive and ordered him to return to Savannah.

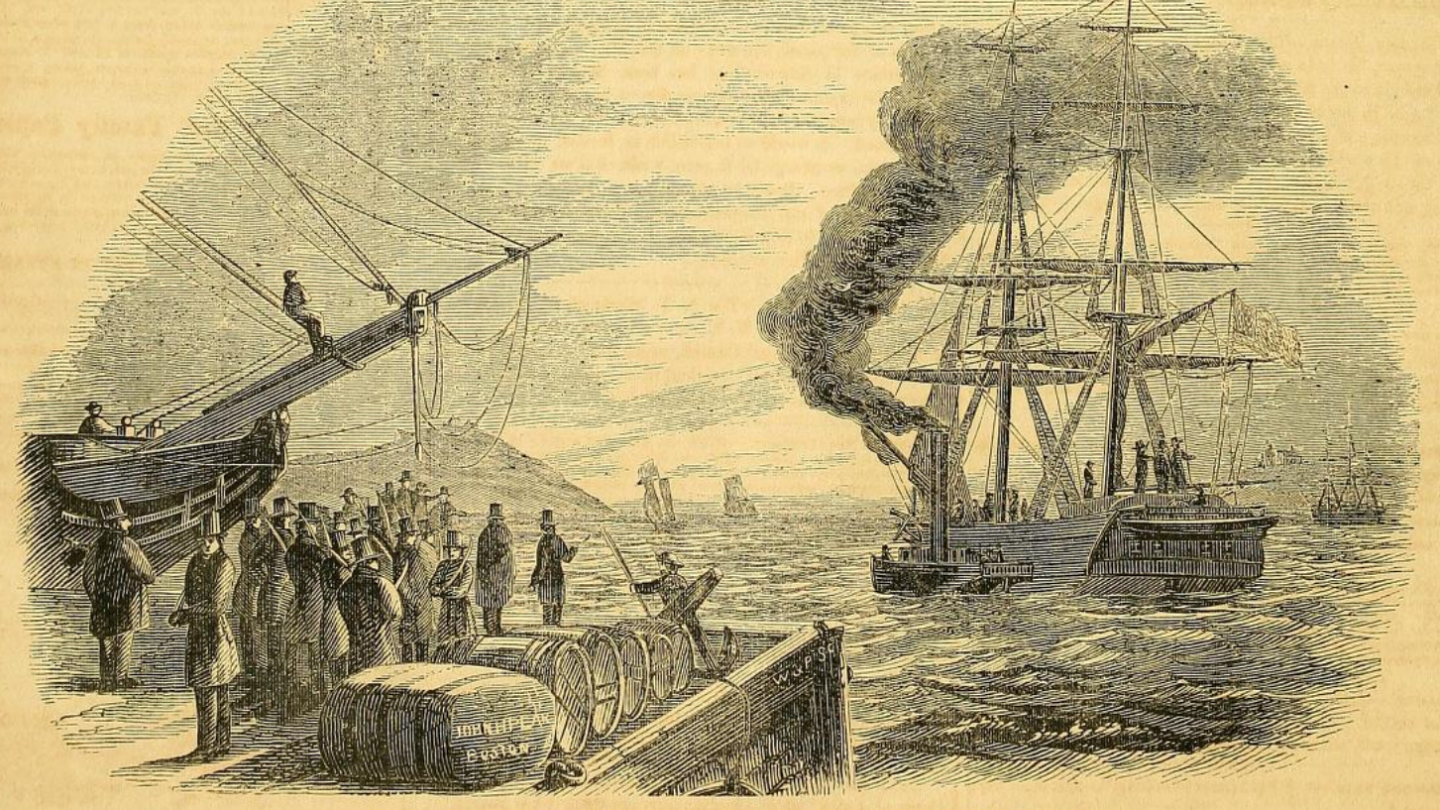

Thomas Sims’s departure for Savannah (“Departure of the Brig Acorn from Boston Harbor With Sims on Board,” anonymous artist, Worcester & Company, engraver, from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, Boston: Frederick Gleason, publisher, 1851; Boston Athenaeum Digital Collections)

When back in Savannah, local authorities imprisoned Sims and almost beat him to death. He was eventually sold at auction to a brick mason in Mississippi.

Sims’ subsequent attempt to obtain his freedom came during the Civil War. He had been forced to work as a laborer for the Confederate Army in Vicksburg, Mississippi. In 1863, Sims, his new family, and others escaped by canoe into territory controlled by the U.S. Army.

After relaying important information about Confederate strongholds in Vicksburg and a meeting with General Ulysses Grant, Sims and his family were allowed to go to Boston. In Boston, Sims began a career as an orator before returning to the South to recruit formerly enslaved people to join the U.S. Army.

After the war, Sims lived in Nashville until 1877, when he moved to Washington, D.C., to accept a position at the U.S. Department of Justice under U.S. Attorney General Charles Deval. Deval had been the U.S. Marshal in Boston who arrested Sims after his first escape attempt. Sims was a messenger, likely responsible for delivering packages on behalf of the Justice Department.

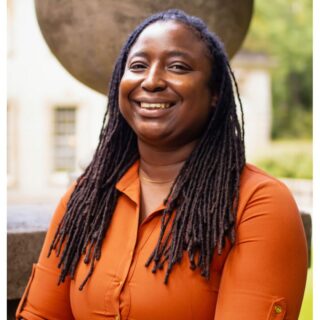

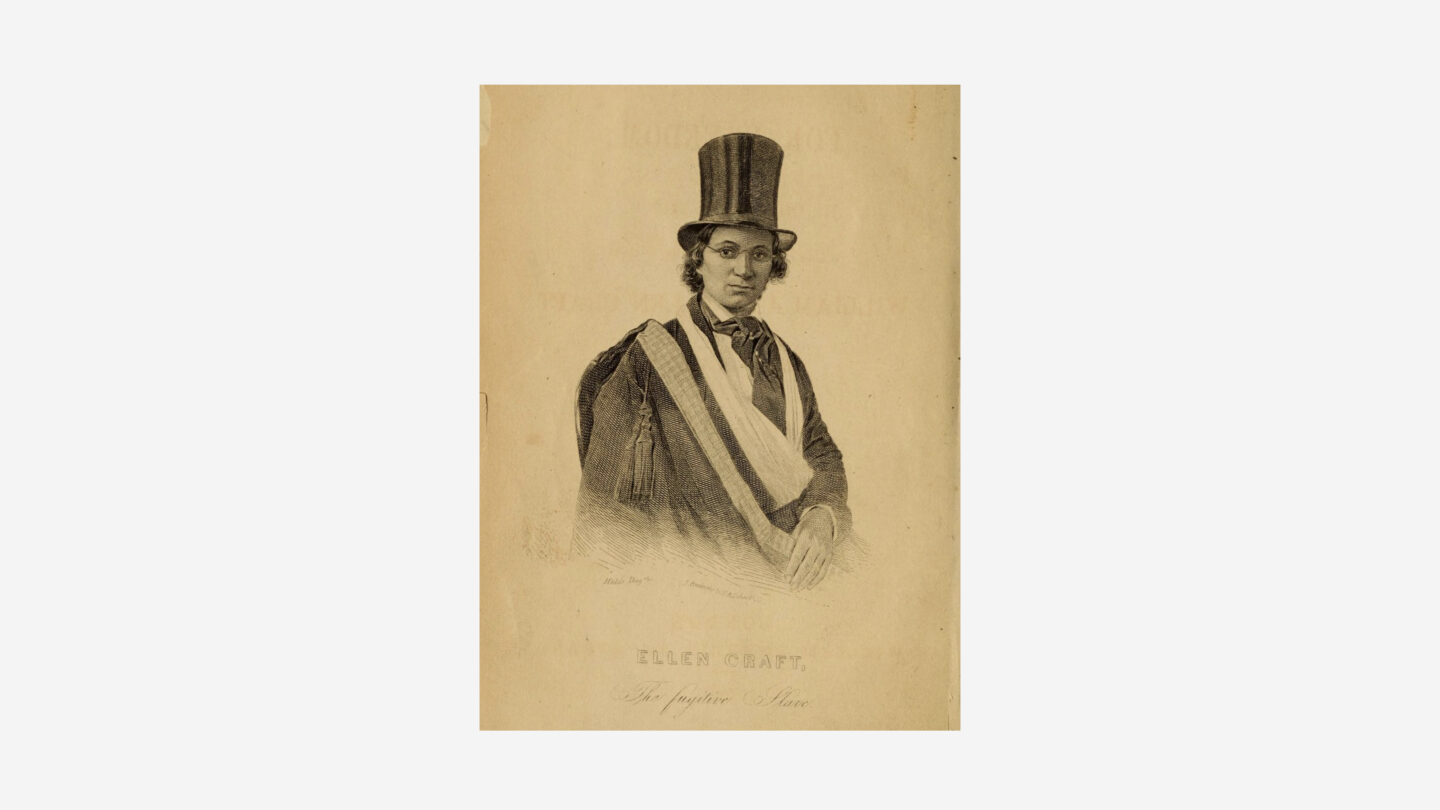

Ellen Craft (1826–1891) and William Craft (1824–1900)

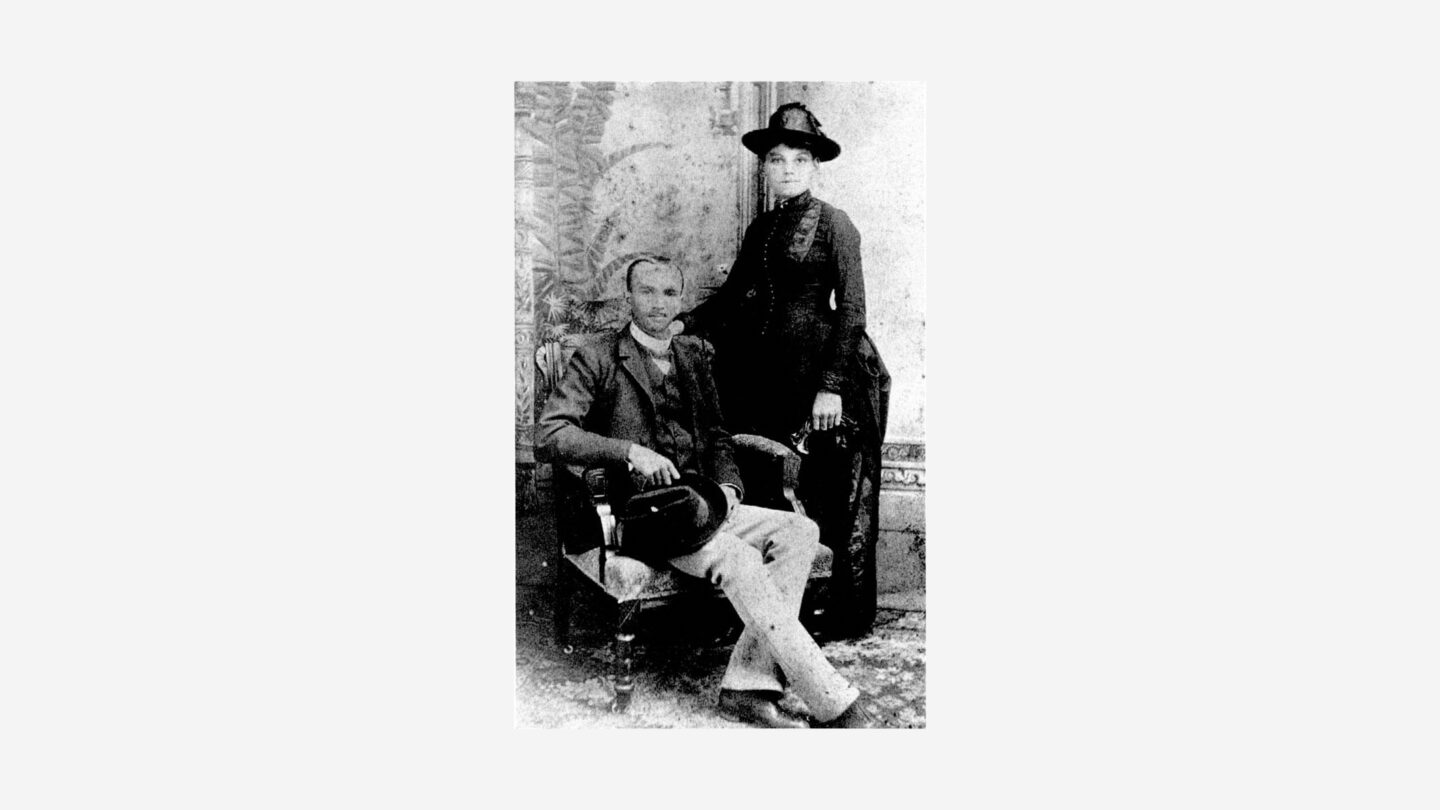

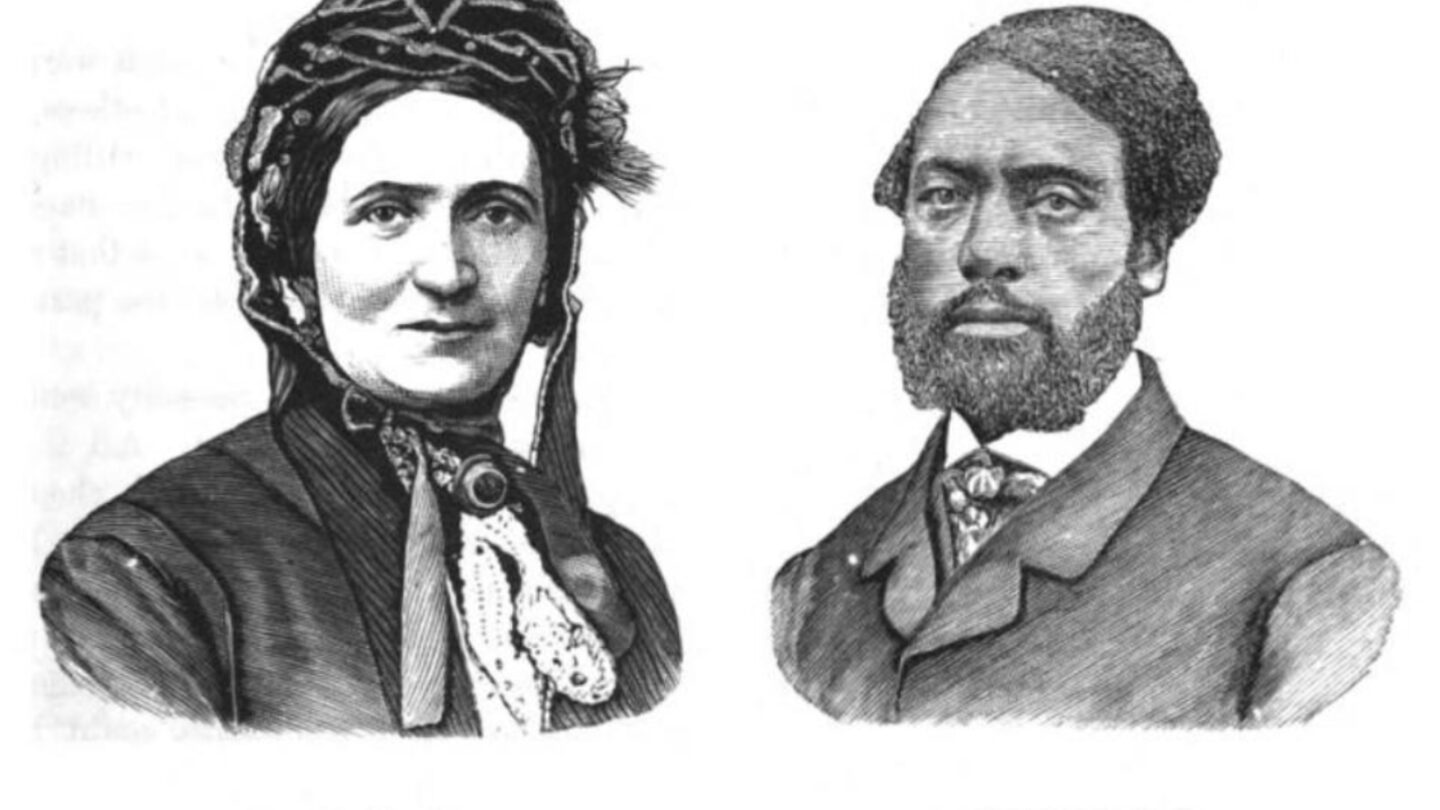

William and Ellen Craft. ( Engraving by Bessell [?] from The Underground Rail Road, William Stills, author, Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, publisher, 1872; New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Enslaved on a plantation owned by Dr. Robert Collins in Macon, Georgia, Ellen and William Craft escaped in 1848. Using an elaborate ruse, Ellen posed as an ill white man and William as “his” faithful servant.

In 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850. The act said that enslaved people who had escaped to free states and territories could be returned to bondage.

Emboldened by the Fugitive Slave Act, Collins sent bounty hunters to Boston to capture the Crafts. When the bounty hunters met resistance from Black and white Bostonians, Collins appealed to President Millard Fillmore. Fillmore decided that the Crafts should be returned to Collins by any means necessary, including military force.

With the threat of re-enslavement, William and Ellen immigrated to England with financial support from abolitionist friends and supporters. William wrote in their 1860 memoir that it wasn’t until they arrived in England that he felt true freedom.

In England, the Crafts settled in London and worked as abolitionists in exile, speaking out against the evils of slavery in the Americas, and as activists on behalf of other issues, such as women’s suffrage.

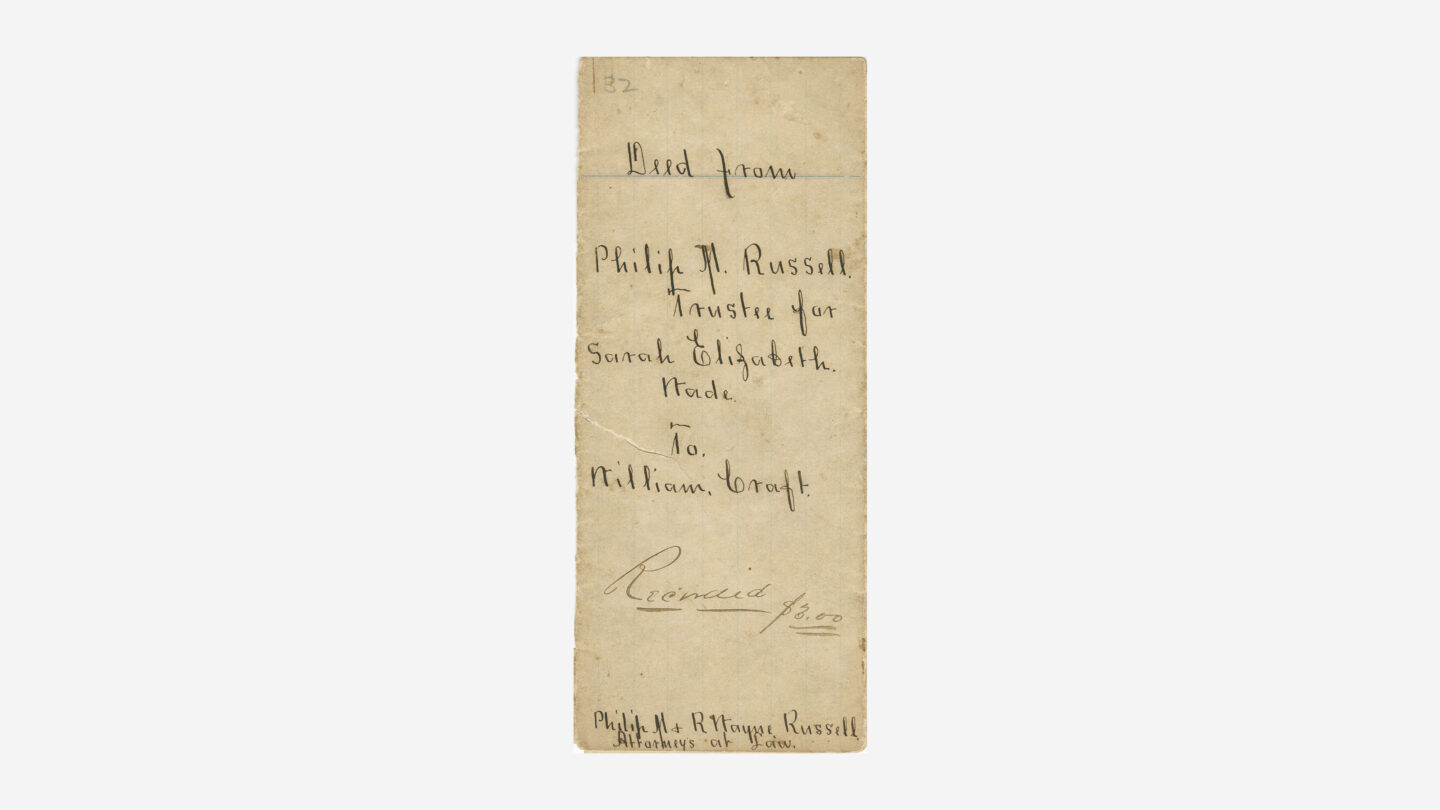

Woodville Plantation deed transferring Woodville Plantation from Sarah Elizabeth Wade to William Craft, 1873. (Craft and Crum Families, 1780-2007, Lowcountry Digital Library, Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston, AMN 1102)

With the end of the Civil War and abolition of slavery, the Crafts and three of their five children returned to the United States where a future in post-slavery America seemed promising.

They purchased Woodville Plantation in 1870. The plantation was comprised of nearly 2,000 acres of land near Savannah. There, the Crafts established the Woodville Cooperative Farm School in 1873 to educate and help employ freedmen. The school closed a decade later amid claims of mismanagement, depressed agricultural prices, post-Reconstruction policies, and racial violence.

Ellen Crum, daughter of William and Ellen Craft. (William and Ellen Smith Craft Photo Album, Lowcountry Digital Library, Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston, AMN 1102)

After the failure of the Woodville Cooperative Farm School, the Crafts moved to Charleston. They lived with their daughter Ellen and her husband, Dr. William Crum. Crum was a wealthy, mixed-race, politically active physician. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Crum to a high-profile position as the first Black customs collector for the port of Charleston. He also served as a diplomat to Liberia from 1910 to 1912. The elder Ellen Craft died in 1891, and William Craft died in 1900.

Amanda America Dickson Toomer (1849-1893)

Amanda America Dickson Toomer, one of the wealthiest Black women in America in the late 1800s. (Woman of Color, Daughter of Privilege: Amanda America Dickson (1849-1893), Kent Anderson Leslie, author, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995)

When her father David died suddenly in 1885, it was like 35-year-old Amanda Dickson won the inheritance lottery.

As David Dickson’s only child, Amanda inherited the bulk of her father’s estate, which included 15,000 acres of land in middle Georgia, 13,000 acres in Texas, railroad stock, and rights to agricultural products (seeds and compounds) that Dickson sold.

Amanda was born in 1849 in Hancock County, Georgia, on Dickson Plantation to David Dickson and Julia Frances Lewis. Julia was a 13-year-old enslaved girl described by Jonathan Bryant in the Georgia Historical Quarterly as “short, petite, copper-colored, with brooding dark eyes.”

David Dickson was a prosperous and wealthy cotton farmer known as the “Prince of Southern Farmers.” He used innovative agricultural techniques, such as the use of guano as a fertilizer and well-trained slave labor, to produce twice as many cash crops as his rivals.

David’s mother, Elizabeth Sholars Dickson, was Amanda’s legal owner. As a child, Amanda learned to read, write, play the piano, and behave like a socialite.

Just 20 years after the end of the Civil War, her inheritance with an estimated worth of about $1 million (as much as $30 million today) made Amanda one of the wealthiest Black women in America. The inheritance also possibly made Amanda one of the most hated Black women in America, as David Dickson only bequeathed his white relatives about $30,000. Nearly 80 of David Dickson’s relatives contested his will. Their main argument was that enforcing the will would upset the racial status quo and encourage fornication and interracial marriage.

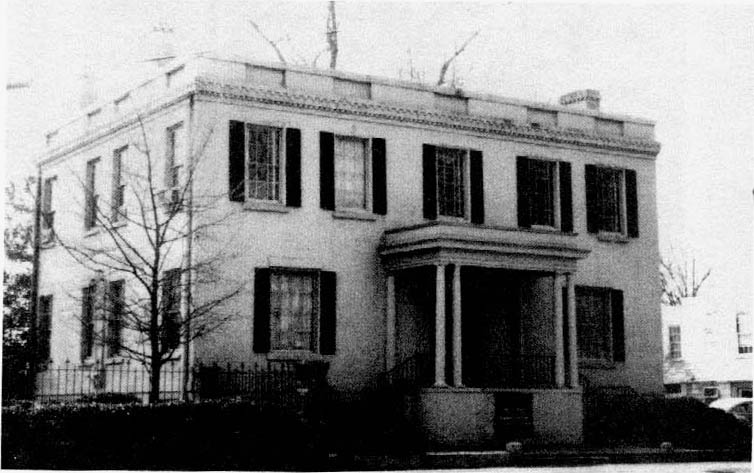

Amanda Dickson’s house in Augusta, Georgia. (Woman of Color, Daughter of Privilege: Amanda America Dickson (1849-1893), Kent Anderson Leslie, author, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995 )

While her relatives plotted to take her inheritance, Amanda left her father’s plantation and moved to Augusta, Georgia. She purchased a large, brick house for $6,098 in a racially mixed neighborhood. While in Augusta, Amanda mingled with the wealthy when most Blacks were being forced into the narrow confines of a post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow reality. Even though Amanda was able to fully integrate into Augusta’s Black “upper class,” due to the racial caste system of the day, whites tended to tolerate, not fully accept, Amanda because she was rich and looked white enough.

The Dickson will contestation case was in and out of court, eventually ending up in the Georgia Supreme Court, where presiding justices ruled that Blacks had the same rights as whites due to the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. The ruling meant that Amanda had the same rights as a white woman regarding inheritance. According to Dickson’s will, Amanda’s estate was for life, and when she died would pass on to her sons, Julian and Charles. Julian and Charles were Amanda’s sons from a common-law marriage at age 16 to her white first cousin, Charles Eubanks.

Amanda lived as a wealthy socialite for the next seven years, and was noted for her “wealth, elegance, and intelligence.” In 1892 when she was 43, Amanda married Nathan Toomer, a mixed-race farmer from Perry, Georgia. It was the second marriage for both.

Amanda was sickly throughout the marriage and was ultimately diagnosed with neurasthenia, an exhausted nervous system. Despite all she had endured to receive her inheritance, Amanda died on June 11, 1893, without a will. Her funeral was held at the Trinity CME Church in Augusta and she was buried at Cedar Grove Cemetery.

Friends described Amanda after her passing as “To her mother she was all that a dutiful, loving child should be. As she lived, so she died, a gentle, sweet spirit.”

Amanda’s mother, Julia, husband, Nathan Toomer, and son Julian fought for control of her estate after her death, ultimately settling out of court.