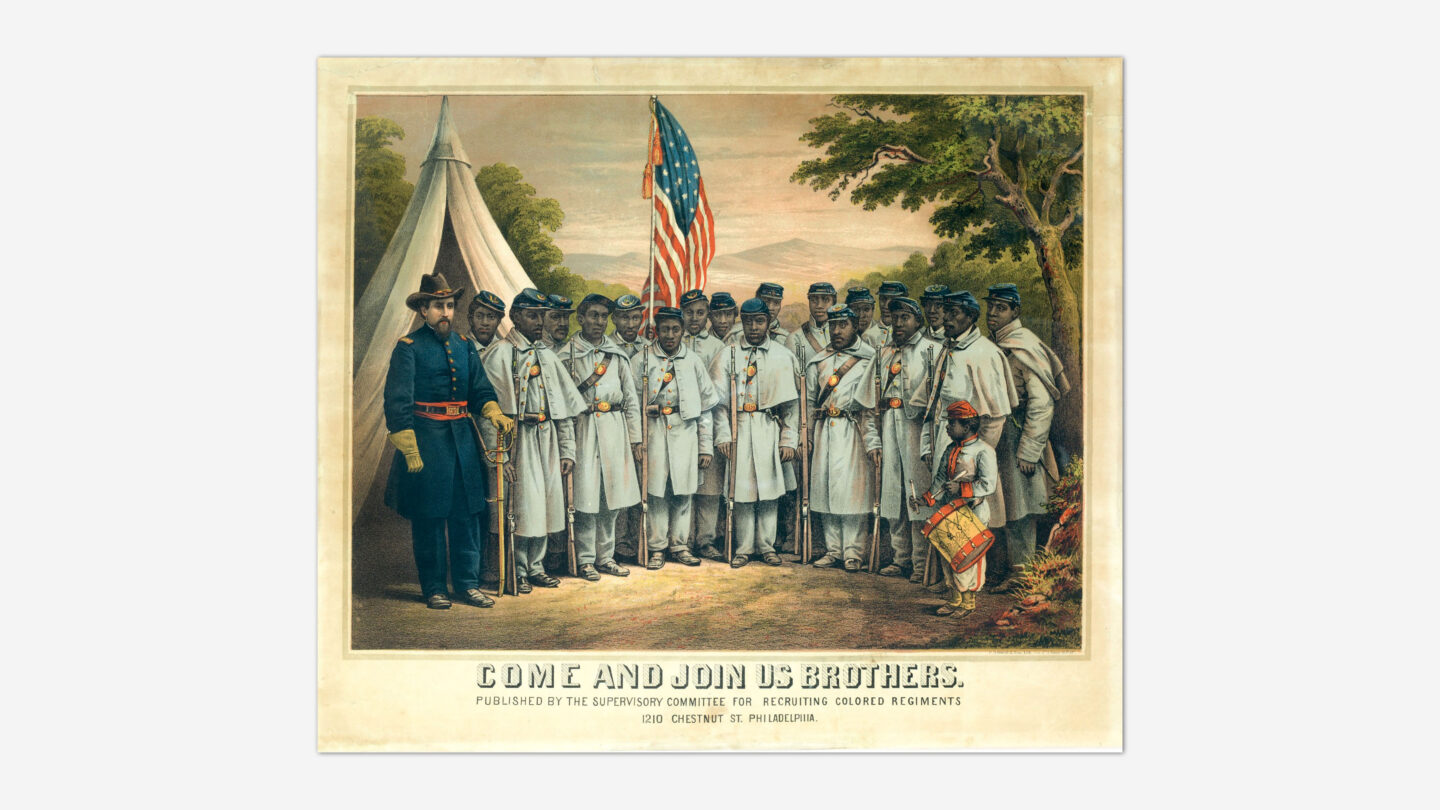

A recruitment poster that reads, “Come and Join Us Brothers” distributed by the Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Troops. During the Civil War, the Bureau of Colored Troops used recruitment posters such as this to entice African Americans to enlist and become United States Colored Troops. (Smithsonian, National Museum of American History)

Samuel Cabble, like any other 19-year-old, joined the U.S. Army for familiar reasons. He joined for his country. He joined for his family. He joined for his faith. The difference between Cabble and other people who join the military every day is that Cabble had just escaped from enslavement in Missouri and was fighting to maintain his freedom.

Cabble (also spelled Cable) served with the 55th Massachusetts Infantry and was one of more than 200,000 people of color who served in the U.S. Army or Navy during the Civil War.

The United States Colored Troops were established in May 1863, a few months after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people in the Confederate-controlled areas of Southern states. The Bureau of Colored Troops oversaw the growing number of formerly enslaved and free people of color who joined the military to fight for the Union. The 54th Massachusetts (famous for its attack at Fort Wagner, S.C., in July 1863) as well as the 55th Massachusetts (recruited at the same time as the 54th) were among a handful of Black regiments allowed to retain their state volunteer designations instead of being re-numbered as USCT regiments.

The USCT was comprised of 135 regiments of infantry soldiers. In addition to infantry, the USCT had 13 heavy artillery, six cavalry, and a light artillery regiment. The people of color who were not allowed to enlist, such as women, helped the war effort by being cooks, spies, nurses, and scouts. Although a small number of Black soldiers received officers’ commissions towards the end of the war, and many served as noncommissioned officers (such as corporals and sergeants), the USCT was primarily commanded by white officers.

Before the establishment of the USCT, many whites (even Lincoln) were skeptical about African Americans joining the U.S. Army, but the soldiers of the USCT consistently demonstrated their courage and dedication.

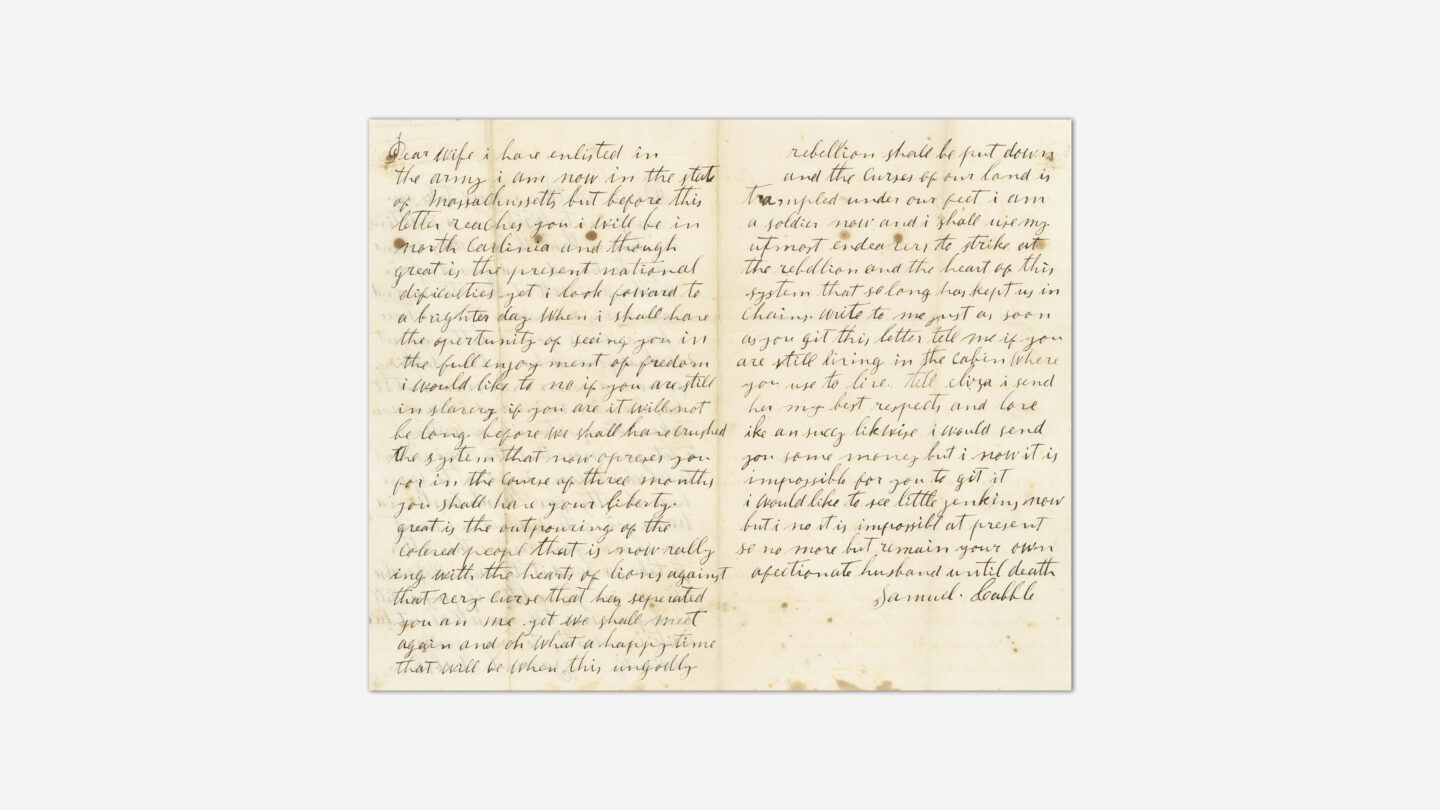

Soon after he joined the army, Cabble wrote a letter to his wife that showed his passion for his mission. He wrote, “great is the outpouring of the colored people that is now rallying with the hearts of lions against that very curse that has separated you an me yet we shall meet again and oh what a happy time that will be when this ungodly rebellion shall be put down and the curses of our land is trampled under our feet i am a soldier now and i shall use my utmost endeavor to strike at the rebellion and the heart of this system that so long has kept us in chains . . . remain your own affectionate husband until death.”

A letter from USCT Pvt. Samuel Cabble to his wife. In the letter, Cabble, who had been enslaved before the Emancipation Proclamation, told his wife that he looked forward to enjoying his freedom with her. (National Archives)

The United States Colored Troops proved themselves as fighting soldiers on the battlefield. Army officials initially assumed that Black regiments would rarely see combat. Instead, these regiments ended up fighting in virtually every major military campaign in which Union armies were involved during the last two years of the Civil War. About 3,000 USCT soldiers were killed in combat, while another 68,000 died of disease, a death rate far higher than for white troops. Additionally, members of the USCT were awarded at least 18 Medals of Honor.

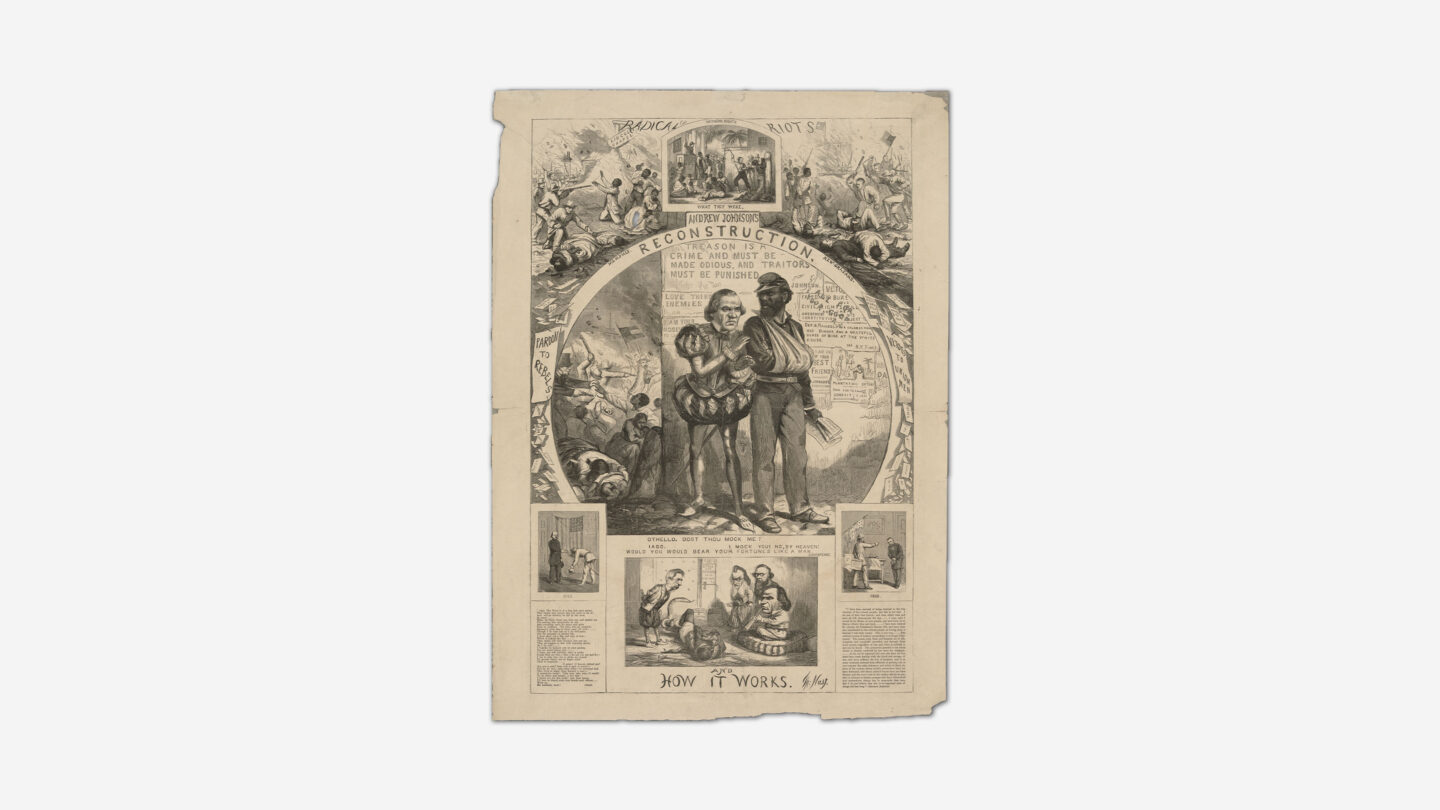

Editorial cartoon by Thomas Nast portraying President Andrew Johnson as the Shakespearian villain, Iago, who betrays Othello, portrayed here as an United States Colored Troop. (Library of Congress)

After the war, discharged USCT soldiers had to build new lives for themselves, finding lost family members, building new communities, and making their way as free citizens in a country rife with racism and discrimination. Records show that Cabble returned to Missouri to legally marry his wife before moving to Denver, where he lived until his death in 1905 of renal failure.

However, before he made the trek back to Missouri, Cabble purchased his army-issue rifle-musket when he was mustered out of service. Like many of his comrades, he thought he might need it for self-defense when he returned home. Thomas Baker, a drummer in the 55th Massachusetts, had no rifle to bring home, but instead purchased his army drum. That drum is now on exhibit in the upstairs gallery of Cyclorama: The Big Picture.

Most USCT veterans found that their military service at least earned them trust and respect within the Black community. And during Reconstruction, some USCT veterans were able to take advantage of the freedom they fought so hard to obtain by being elected to state legislatures and the U.S. Congress.