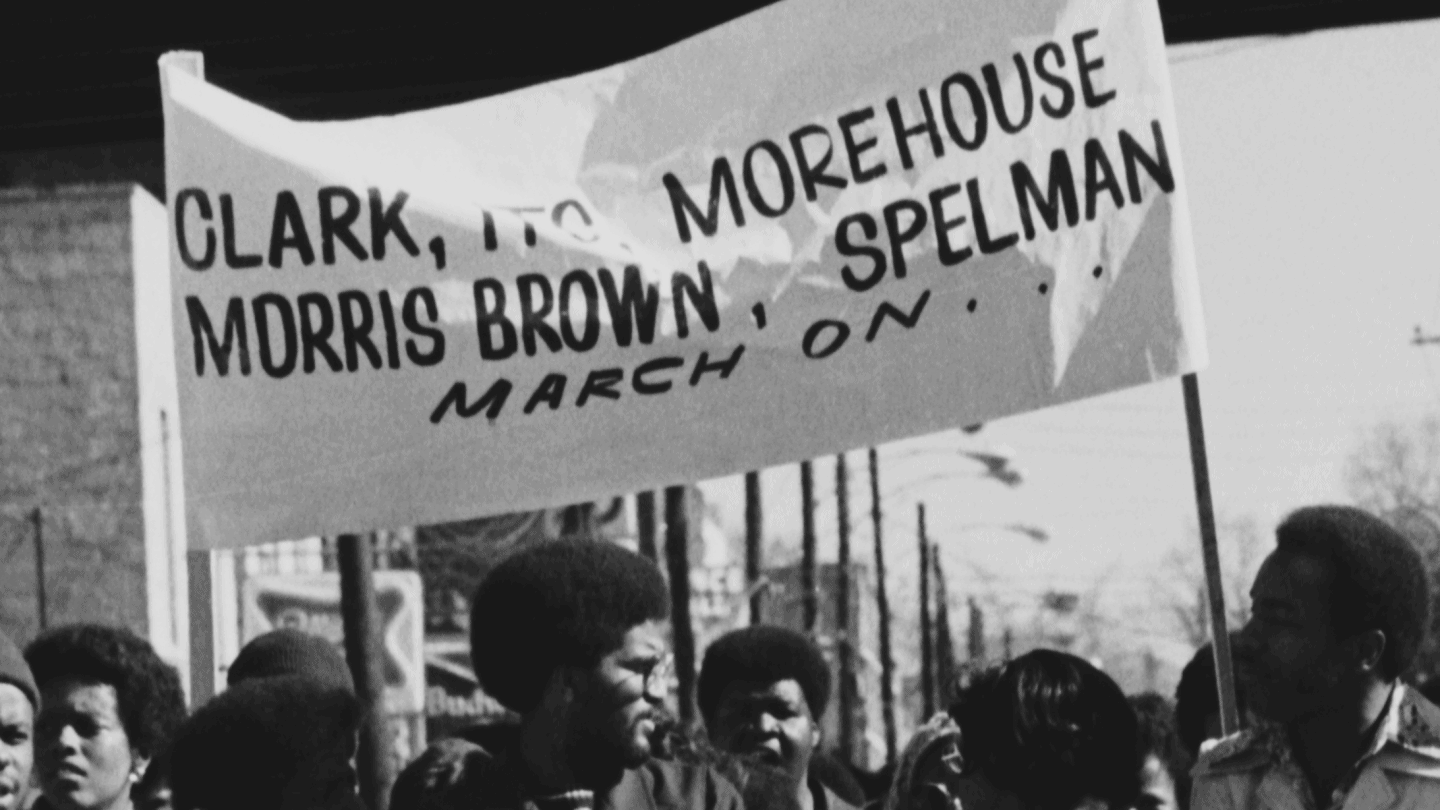

Students march down Auburn Avenue commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 47th birthday, January 15, 1976.

The deaths of Atlanta’s own Constance “Connie” Curry, Congressman John Lewis, and Reverend C.T. Vivian signal the ongoing passage of responsibility to those of us who are making history today. The legacies of these three key figures of the Civil Rights Movement live on in the works of contemporary Atlantans.

In order to map the profound and wide-reaching impact of Curry, Lewis, and Vivian, we reached out to some of our city’s modern-day history makers to ask how these legacies influence their work, thinking, and personal philosophies. “Every generation leaves behind a legacy,” wrote John Lewis. “What that legacy will be is determined by the people of that generation. What legacy do you want to leave behind?”

This living document serves to share stories from artists, writers, educators, and other members of the community impacted by the teachings of Curry, Lewis, and Vivian. We invite you to revisit it often as more stories will be added in the coming weeks.

Growing up as a Black girl in metro-Atlanta, with downtown Atlanta at my fingertips was so special. This “Black mecca” inspired me to dream bigger than many of my peers growing up in other cities throughout the country. There were Black electrical engineers (like my dad), doctors, entrepreneurs, architects, politicians, and more all around me. I remember when our next-door neighbors, one of whom was a prominent Black lawyer, had a dinner party and Johnnie Cochran was there — casual. This was only a few years after he became a household name during the biggest trial of the decade, where he famously uttered, “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” Black history makers always found their way to Atlanta.

Riding down streets named after civil rights activists whose lives had directly impacted the Atlanta that I was fortunate enough to grow up in, such as Andrew Young International Boulevard, Donald Lee Hollowell Parkway, Ralph David Abernathy Boulevard, Xernona Clayton Way — what a privilege. All of those moments informed who I am today, but the man who Freedom Parkway is now named after has been the force that lifts me up every time our country has left me heartbroken and knocked me off my feet.

No, I never had the pleasure of meeting Congressman John Lewis, but I — like so many others — felt so deeply connected to him. I’d seen the photos of him leading the march across the bridge in Selma and getting hit in the head before ending up in the hospital with a fractured skull. I’d seen images of him speaking at the March on Washington. I’d seen images of President Lyndon B. Johnson handing him the pen used to sign the Voting Rights Act.

I had also seen images of him with our country’s first Black president.

He’s one of those rare figures in history who lived long enough to see the positive results of his actions. Unfortunately, he also had to see his life’s work come under attack with the dismantling of the Voting Rights Act over the last several years. I think that’s what hurt the most. That he fought until his last breath, and that this country created the circumstances that forced him to fight his entire life. For that, our nation should be so deeply ashamed. Nonetheless, because of that — because of John Lewis — I know that the fight is worth it, and that the courage to carry on and push our country to become the “land of the free” it claims to be, lives in me too.

Lewis’s legacy will live on through my work in so many ways, but perhaps the most significant will be my willingness to keep going. I can’t help but wonder if and when there will be a generation of Black folks who aren’t burdened with this fight for equality. All I know is that John Lewis has passed us the torch, and I’m prepared to honor his life by continuing to march on.

I owe my career as an archivist to the documentary series “Eyes on the Prize,” and in part, to the Reverend C.T. Vivian. That remarkable television series was a visceral experience for a 19-year old college sophomore that taught me history in ways a classroom could not. As incredible as the footage of those events were, it was the compelling interviews of participants in the Civil Rights Movement that left me transfixed. I had to find a way to become immersed in this way of learning, and three years later I began my career. That was 1991.

My clearest memory of that first viewing was an interview with C.T. Vivian who described what it meant to confront the oppressive forces of white racism in Selma, Alabama.

“It was a clear engagement between those who wished the fullness of their personalities to be met, and those that would destroy us physically and psychologically. You do not walk away from that. This is what movement meant. Movement meant that finally we were encountering, on a mass scale, the evil that had been destroying us on a mass scale. You do not walk away from that; you continue to answer it.”

Selma’s Sheriff, Jim Clark, had punched and bloodied Vivian who afterward continued to stand and deliver a fierce lecture to Clark and his posse on the meaning of democracy and justice. What first compelled me was his courage in taking a beating for his principles. But I learned only many years later that it was nothing for Vivian to be physically beaten. In verbally confronting Clark, he was demonstrating to Clark and the people who he was attempting to register to vote what commitment to the Movement meant. What was important to Vivian was “reaching the conscience of those who are with you and the so-called enemy.”

John Lewis was the embodiment of everything that makes Atlanta’s a special place. Butter.ATL was started to highlight the people, places and things shaping modern day Atlanta. Yet, none of that would be possible without the work done by leaders like him and so many others. Butter.ATL commits to using our platform to continue John Lewis’s legacy of Good Trouble.

Nearly 60 years after the Civil Rights Movement, here I stand: great-granddaughter of Irish immigrants, raised in the South by Yankee parents, trying to find my own place in the movement. The recent deaths of civil rights heroes John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, and Connie Curry seem an almost insurmountable loss; one that has hit our Atlanta community especially hard. As thousands of Americans take to the streets to protest police brutality and to fight for the rights of BIPOC, LGBTIQ, and immigrant communities, I am reminded of Rep. John Lewis’ powerful words to Congress:

“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something, to do something. Our children and their children will ask us, “What did you do? What did you say?”

As a white woman, I look to Connie Curry as an example of true allyship: being consistent, building trust, standing up, speaking out, and recognizing that as white people, we benefit greatly from institutionalized racism and white privilege. Acknowledging this privilege does not mean one’s life has not been difficult, but rather that the color of your skin has not made it so. For decades, Americans have been fighting to dismantle systemic racism in policing and other institutions that disproportionately kill and oppress people of color. It is our duty as anti-racists to now remove the burden from our BIPOC communities and carry that weight for them. John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, and Connie Curry left a beautiful legacy for us to uphold; one of joy, hope, and a never ending pursuit of justice and equity. We must now take up their cross and actively choose to be better and to do better.

I first met John Lewis in 1980 and that meeting led to deep friendship with John, his wife, Lillian, and their son, John Miles. I fell in love with John Lewis and all he stood for and he would become an important part of my life, an important friend of Inman Park, intown neighborhoods, the City, the State, and the country.

When John ran for a city-wide seat on the Atlanta City Council in 1981, we hosted several campaign parties at our Hurt Street house to help John’s campaign and introduce him to neighbors. We were thrilled that John won and would represent Inman Park.

As our city councilperson, John supported the neighborhoods during the 10-year battle against construction of the parkway that would have destroyed intown historic neighborhoods. John was not swayed by pressure from former president Jimmy Carter or Mayor Andy Young. John always supported his friends and constituents and fought for what was right.

In 1986, John was elected to the US House of Representatives and we all took the train to Washington DC to witness John’s swearing in. Forty people took over the train and the club car, ate homemade Jambalaya (made by my husband, Wayne Wall), and had an all-night party. After being sworn into Congress, John was appointed to the Appropriations Committee. John asked Inman Park to host a brunch for the Chairman of the Appropriations Committee to be held at our house on Hurt Street. John invited the Commissioner of Georgoa DOT and top officials in GA and Atlanta to attend. Bloody Marys accompanied the discussion of one topic—stopping the road through our intown neighborhoods. John taught us how to “get in good trouble.”

John was so thrilled at the parties that Inman Park threw for him that he asked us to fly to Washington, DC and throw a party at the Democratic headquarters. We jumped on a plane, along with Deacon Burton, his well-seasoned cast iron skillets, pot & pans, and the ingredients for a “Southern Fried Chicken and Mint Julep Party” for all the Congressional Democrats. This was so successful, we returned for parties over the next three years.

During the 1988 Democratic Convention in Atlanta, John asked me to organize and host an event in Inman Park. We called it “Victorian Nights – Victorious Days”. Forty members of Congress and a multitude of friends attended. We closed Elizabeth Street, had homes on tour, served Mint Juleps and hors d’oeuvres, held a Victorian Parade with two bands as neighbors and children were adorned in Victorian attire. Our famous chef, Deacon Burton, drove a horse & carriage with Honorable John and Lillian Lewis smiling and waving to all. Press attending were CBS Dan Rather, NBC Harry Smith, 60 Minutes Ed Bradley, AJC, Washington Post and USA Today. There was also a brunch for all the dignitaries at our house on Hurt Street with my husband, Wayne, once again serving his famous Jambalaya and Bloody Marys.

Every year at the Inman Park Festival, John, Lillian, and their son, John Miles parked at our Hurt Street house to attend the annual festival parade party where they would meet with elected officials, old friends, neighbors, and many of his constituents. Often, John would be in the parade laughing, waving, shaking hands, and hugging everyone along the parade route.

We all have favorite memories of John, the gentle warrior, the extraordinary human being, our Hero. No other like him shall we encounter through our journey on earth. We so loved him. As John said at the 50th Anniversary of the Road Fight and again at the taping of his story at Atlanta History Center, “I love Inman Park and Inman Park loves me”.

When John died, part of Inman Park died. Certainly, a huge part of me died. I will miss my early morning phone conversations with John, just like I miss my friendship with Lillian Lewis since her death in 2012. They are both gone but live on in the hearts of Inman Park.

I don’t take it lightly growing up in Atlanta which is coined as the home of the Civil Rights Movement. A movement centered on nonviolence demonstrations to eradicate racial prejudices and acts of hate toward citizens of color. One Civil Rights Activist, W.E.B DuBois, who taught in the University Center (AUC) in the1930’s would also say to his students, “our freedom is sought through education!”

Living in the heart of the AUC and having neighbors who were students of Professor DuBois, I became no stranger to the passion and call to social activism. In the early 90’s there were a series of initiatives in public schools. For me, the reading initiative in the form of a storytelling series was the best one. Mainly because I loved reading and I quickly learned when dignitaries come to schools, they always take photos reading to children. When leaders such as Coretta Scott King, Rev. Dr. Joseph Lowery, Rep. John Lewis, Rev. Dr. Ralph David Abernathy and others would come to elementary schools in Atlanta, of course out of their enjoyment too, they would read and share stories with us.

I was in elementary school when I first met Rev. Dr. C.T Vivian. Rev. Vivian as well as Rev. Dr. Joseph Lowery, were big supporters of the reading initiatives. After reading there would be questions from students. Rev. Vivian would say, “Ah, I see we have a young preacher here!”, if you were well spoken. Their impact through storytelling has impacted my life and career. In fact, many years after graduating from APS, I became a teacher within the district. I was able to help implement assembly programs and reading initiatives at my community schools where our then living legends came back to share their stories, experiences and of course read.

1996 was a monumental year for the City of Atlanta. We all watched as Muhammad Ali carried the Olympic torch. It was also monumental for me as a middle school student. Ambassador Andrew Young came to our middle school, named after his wife Jean Childs Young, and talked about the importance of “Carrying the Torch”.

In my notes, what stands out to me to this day is this statement he made. “You can’t successfully carry a torch if you don’t know it’s weight!” Now as a teenager, my mind went right to the point of making sure that if I carry a torch, don’t get a big one. But in hindsight I realized over time that carrying a torch and knowing its weight truly means to understand and know the value of what you’re carrying.

For me, carrying the torch for civil rights has been something leaders, teachers and community organizers in Atlanta have been preparing us to do. It was an intricate part of my schooling upbringing and community. Several of my classmates, now in their professional careers, are positively impacting our communities. There are others of us who are also on the frontlines of activism for many of the injustices facing our communities. We’ve taken what we’ve learned from John Lewis, Joseph Lowery, Hosea Williams, C.T. Vivian and many others and we are advocating for affordable housing, better educational outcomes, crime prevention, ending police brutality and even helping find a solution for our Black and brown youth on corners selling water for survival.

As an educator, I utilize the experiences and memories of having been in rooms with several Civil Rights legends to connect the youth of this generation to the work. I’m reminded of Hosea Williams and what he would press upon us during community projects. “We need the young people in the front because they will be the ones leading the way soon!” I have confidence that our civil rights legends will rest peacefully knowing that the torch has been passed and we’re ready, willing and able to carry it onward.

In my four years at Spelman College, there is a single phrase our president repeated more than any other: Service is the rent you pay to live on Earth. Some version of this message has been attributed to Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, Muhammad Ali, Marian Wright Edelman, and, of course, my Sister President Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole. It matters not who said it first. It left a strong impression, reminded us that we had a responsibility to try to help others, was an admonition to never hide our light when we had the power to create change.

It is a lesson that Reverend C.T. Vivian, Constance “Connie” Curry, and Congressman John Lewis imparted each day as they used their lives to make a world where everyone could be fully human: to have access to food, shelter, education, work, a daily life free from the threat or actuality of violence. They didn’t just make speeches, or pass legislation, or participate in protests to effect these changes—though that would have been plenty. They put themselves on the line for it, raised their voices when it was unpopular and they were reviled and shunned for their stances. They suffered beatings and evictions and ridicule. And by staying the course, they taught us that it’s not enough to stand with and for people who are marginalized when public sentiment is on your side or there’s a mic in your face. Rather, true leadership, true changemaking is wrought be raising your voice even when it is terrifying and you feel you are standing alone and there is much to lose.

I did not know Reverend Vivian though I met him a few times. I remember that, on each occasion, he was interested in hearing others’ speak as much as in sharing his view. He seemed to assume that every person in the room had equal worth and did not first assess their position. His carriage reminded me of my grandmother’s oft-repeated wisdom that, “A trul y great man will treat the janitor with the same respect as the president. Every time.”

In Connie, who I knew personally, I witnessed the same humility. As a woman, I especially appreciated the beauty with which she balanced that humility with an insistence that she wasn’t going to diminish her light or wisdom when it was needed. She was uncompromising in this and yet still had compassion and showed kindness to people who opposed her.

Certainly, Congressman Lewis was the embodiment of that delicate poise matched with determination and strength of character. In November 2019, when I had the pleasure of interviewing him, he told me, “When I was growing up in rural Alabama and I would ask…’why this and why that,’ they would say ‘Boy, don’t get in trouble.’ When I asked about those signs that said white men, colored men…they said, ‘Don’t get in trouble. That’s the way it is.’ But I was inspired to get in…good trouble, necessary trouble, and I’ve been getting in trouble ever since.” He said that, while no one sets out to get in trouble, “sometimes you have to use your body, use your ideas to bear witness to the truth.” He noted that it is never too late to learn more about what people suffer and what they need and to lend yourself to that effort. His was a lifelong journey—to apply the courage of his convictions and the activism it demanded to every aspect of his life and work.

While I join the beloved community in mourning the deaths of C.T. Vivian, Constance Curry, and John Lewis, my mind is excited to further explore the lessons they imparted and my heart is filled with hope. In our homes, institutions—throughout the entire nation—we are in the midst of a storm. Now, as always, we must use our lives to make a world where everyone can be fully human. We must embrace our service with humility and compassion—and yet be unwavering. We must carry the baton, even when it means facing our measure of good trouble.

There are few singular moments that we can recognize as actually changing the course of American history, and fewer opportunities to meet someone who made that possible. Congressman John Lewis’s activism changed American history.

What will always stand out in my memory of my Congressman are the multiple occasions when I had the honor of hearing him speak during the annual commemoration of Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Standing in a place where such brutal violence occurred in opposition to Black people rightfully claiming their basic rights, I will never forget his matter-of-fact tone as he described the beatings inflicted upon him and others by Alabama state troopers. He described how he thought that he would die that day. Importantly, he always described his simultaneous vision for a better country if we would act, by “getting in the way” and making “good trouble.”

My family and I returned year after year to experience this moment, never stagnant, but always resonate when layered over the current events of the given year. While this year, the crowd was so large that we weren’t able to get close enough to hear his words, the image of him returning, strong despite Stage 4 Cancer, to the place where he had suffered 55 years before was beyond poignant. His message of relentless self-sacrifice and racial healing has never been more relevant.

The additional losses of C.T. Vivian and Connie Curry in such a short time brings home the message that we must take up the mantle: to vote, and to listen more carefully to the 20 year old’s who are currently “getting in the way.”

Atlanta’s rich history as a leader in movements promoting equal human rights is shaped by the brave men and women who have come to call it home throughout the 20th century. As we enter further into the new millennium, the passing of these monumental figures forces Atlanta, and more broadly the nation, to reflect on their contributions as we mourn these protectors of justice and equity. With the passing of figures like Congressman John Lewis, Reverend C.T. Vivian and Constance Curry, I am reminded of the impact of their legacies on my journey in the realm of social justice.

As the founder and director of the Atlanta Resistance Revival Chorus, I work with my choir to preserve the connection of music and protest. Music is the universal language. It can amplify the voices of many until they simply can’t be ignored. That is just what Lewis, Vivian, and Curry each did in their own way, added their voices to the choir of calls for justice until they couldn’t be ignored.

No one is voiceless. That is what I have learned from each of these brave pioneers. Instead, we each have a voice that, no matter the strength, when joined with a chorus, the power becomes limitless. That limitless power was harnessed by Congressman John Lewis, Reverend C.T. Vivian and Constance Curry throughout each of their lives as they cemented their life’s work as freedom fighters.

Now, as we enter new fights for justice and new struggles for freedom, we carry on their legacies and modify the chorus’s tunes, just as each of these leaders did before us. Through the adaptation and spread of songs like We Shall Overcome, Woke Up This Morning and Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around by the Freedom Singers and other members of SNCC, the importance of music in the movement was cemented in history. As we progress further, so do our songs. We adapt the old and write the new to truly express the pain, cries for justice, and cheers for action.

However, one thing remains the same as we stand in the light of such monumental legacies. We sing messages of hope, messages of a better tomorrow, and messages of true justice. As Congressman John Lewis, Reverend C.T. Vivian and Constance Curry taught us in each of their lives, when we join our voices and sing together, we can carry on the melody, even after key voices are no longer with us.

If you’d like to share your memories of Connie Curry, John Lewis, or C.T. Vivian, we invite you to do so using this form. Your responses, along with those included in this story, will be submitted to our Atlanta Corona Collective, an initiative that illustrates how people are experiencing and responding to all aspects of life in Atlanta during the COVID-19 crisis.