Atlanta Black Crackers before a game. Courtesy of Negro League Baseball Museum.

In April 2021, Major League Baseball announced that they were moving the 2021 MLB All-Star game from Atlanta to Denver. The announcement came nearly two years after Atlanta was initially awarded the game.

MLB made the controversial decision to move the game after Georgia lawmakers passed the Election Integrity Act of 2021, a law that not only changes how elections are conducted in Georgia, but also, some argue, restricts the rights of voters of color.

Those who protested MLB’s decision did so because a conversation about politics and race felt like an unnatural corruption of America’s favorite pastime.

The controversy is symbolic of a long-standing historical connection between race, politics, and sports in metro Atlanta and beyond—one that is perhaps best illustrated by the story of the Atlanta Black Crackers.

Before the Atlanta Braves became World Series champions and introduced Atlanta as a baseball powerhouse with players like Hank Aaron, there were the Atlanta Crackers and their Negro League counterpart, the Atlanta Black Crackers.

Though the story of the Atlanta Crackers is well-known, for years, the story of the Atlanta Black Crackers was largely untold.

This is likely due to their obscured history and the limited emphasis placed on showcasing and enshrining the success of Black players. But the Atlanta Black Crackers’s impact was not forgotten by the Black Atlantans who were given a chance to partake in America’s pastime—and to find their own heroes on the field.

According to former Atlanta Black Cracker, James “Gabby” Kemp, and others from this era, the Atlanta Black Crackers were arguably one of the best professional baseball teams to play in Atlanta.

The Atlanta Black Crackers began as the Atlanta Cubs in 1919. The team was founded when a group of local businessmen recruited athletes from local Black colleges and universities such as Morris Brown College and Morehouse College, along with Atlanta baseball players. By the end of its first season, the Atlanta Cubs had adopted a new name: The Atlanta Black Crackers.

At that time, according to journalist Francis Ward, nobody thought it was unusual for an all-Black team to call itself “crackers.”

“People didn’t regard the word cracker as synonymous with being an ardent white racist the way we do today,” said Ward, recalling his childhood support of the Atlanta Black Crackers.

“Because of this habit of the Black team adopting the name of the White team, nobody really thought that much of it then. But today, one would regard this as very strange—a Black baseball team calling themselves the crackers.”

Atlanta Black Crackers replica jersey, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

Entrepreneur W.J. “Bill” Shaw took ownership of the Black Crackers in 1920. He financed much of the team with the profits from a social club that he owned on Auburn Avenue. Some of the players on the Black Crackers even played in the club’s orchestra.

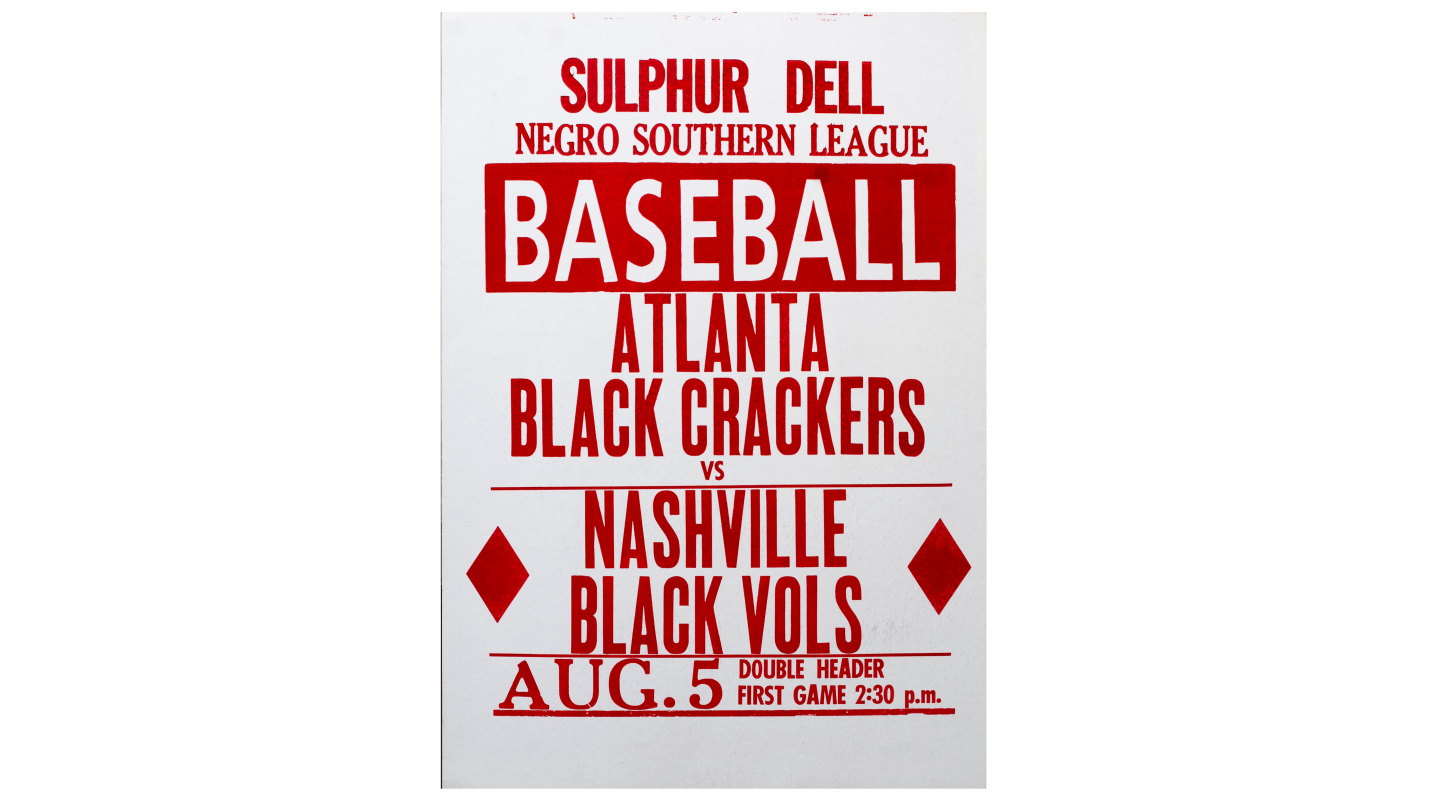

That same year, the Atlanta Black Crackers joined the Negro Southern League which was a subgroup of professional Black baseball teams under the greater umbrella known as the Negro Leagues. The Negro Leagues also began in 1920 and eventually disintegrated in the decades following the racial integration of Major League Baseball.

The Black Crackers’ first season was marked by financial struggles: The team had a squad of 12, a measly budget, and hand-me-down equipment and uniforms from the Atlanta Crackers. By the end of the team’s second season in 1921—despite some impressive wins, a higher income from larger crowds, and money saved by travelling to other ballparks—financial issues led to the team’s dissolution.

Due to eligibility problems for the college players on the team, no potential owner could form a strong enough team to return to league play. Finally, after a four-year absence, two businessmen, H. J. Peek and George Strickland, provided the capital to revive the Black Crackers in 1925. The team spent a lot of time on the road playing exhibition games during this era, and did not participate in any Negro League games, making local media coverage of the team from this period scant.

The team officially returned as members of the Negro Southern League in 1926. They traveled by car instead of rail as a cost-saving measure.

Despite this course of action, the club went bankrupt before the end of the season, returned in 1927, then shuttered again.

“We just didn’t have enough finances to operate,” said Arthur Idlett, Atlanta Black Crackers third baseman. “Half the times the teams couldn’t make it because they didn’t have the finances to show up and transportation wasn’t like it is now. We had old automobiles, and sometimes couldn’t get the money to ride the train.”

After the 1928 season, there was no consistent Black professional baseball team in Atlanta. There were various attempts to create new teams, but all failed due to disinterest from players or financial troubles. Despite this failure, baseball play among Black players continued in local sandlot and semi-pro clubs.

A decade later, the Black Crackers gained a new pair of owners: John Harden, the owner of a filling station on Auburn Avenue, and his wife, Billie. The Hardens purchased the team after seeing games in town and hearing the lively discussions of Atlanta baseball players who congregated at their filling station.

The first seasons under the Hardens saw some of the team’s most successful years. Interest in Black southern baseball flourished as the Black Crackers faced teams in the northern Negro National League. Players such as power pitcher Jim “Pea” Green and flashy first baseman James “Red” Moore helped the Black Crackers execute some dramatic sweeps of other strong teams, earning the team a spot in the 1938 Negro League World Series.

Gabby Kemp, who manned second base during his time with the Atlanta Black Crackers, attributed the team’s success to their skill.

“The Black Cracker ball club was one of the best ball clubs baseball has ever seen in the North or South. This team was well-rounded,” he said.

“In this ballclub, we had some good hitters. Pelham, during the season, would hit anywhere from 30 or more home runs. Donald Reeves, a big, tall, strong athlete from Clark [Atlanta] University, was hitting around 30-45 home runs. [Pea] Green, 15-20 home runs; Red Moore, 10-15; Kemp, 5-12; [Oscar] Boone, 9-15, and Philly Holmes, 15-30. Therefore, our ballclub could produce runs. We had an almost airtight infield.”

The Black Crackers—in the periods that they were able to play in Atlanta and were in operation as an official team—played at Ponce de Leon Ballpark, the home of the Atlanta Crackers. They paid the Crackers’ general manager Frank Reynolds to use the ballpark while the all-White team was traveling.

“The Hardens made it their business to keep a good team in Atlanta to play when the White Crackers were out of town,” said Joel Smith, a sports journalist who covered the team for the Atlanta Daily World.

The Black Crackers’ games at Ponce de Leon Ballpark attracted solid crowds, including white fans. Though Black and white fans were allowed in the same venue, they watched games separately as there was segregated seating—Black fans sat in the bleachers, and white fans sat in the grandstand.

Despite Jim Crow era mores, when the Atlanta Black Crackers played at Ponce de Leon, the team had a level of access that was beyond the norm at that time.

“I was lucky because most of my dealings were with Mr. [Earl] Mann who owned the baseball park. If I had any problem, I could take it to Mr. Mann. And if any changes were to be made, he would always notify me,” Billie Harden said. “When we had the game, we were playing there. We had access to the park. The whole park.”

The Black Crackers’ treatment at Ponce de Leon Park contrasted with their experiences away from home.

“In some towns, they had White ballparks and frequently Negro baseball teams weren’t allowed to play in those parks,” Kemp said. “So, we had to get some place that the man had roped off and play—in those days we called them ‘cow pastures.’”

In addition to playing in open fields, Black baseball players often had to dress and shower at home before arriving at games because they weren’t allowed to use the dressing rooms at white ball clubs.

When the Atlanta Black Crackers were not in Atlanta, they would play games against Negro League teams and exhibition games against white teams. The team made most of its money from exhibition games, according to Atlanta Black Crackers first baseman, Red Moore.

On the road, the team usually received warmth and hospitality wherever they had a following.

“It felt real good,” said Moore.

“Your name on a big poster. People were happy to see us.”

However, there were occasions where the reception was less inviting.

“In New York, we played some team, and I think we were the first Black team to have played some of those white fellas because of the reaction,” Moore said. “The atmosphere was different.”

Baseball Glove, James “Red” Moore, 1930–1950, Courtesy Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

During their stint as owners, the Hardens scraped together enough money to buy a bus, an investment in the efficiency of the team’s travel.

Mrs. Harden remembers travel as a difficult ordeal—the couple was responsible for paying for travel expenses including hotels and meals, and the team was often turned away from restrooms, restaurants, and forced to stay in broken-down hotels.

“I can’t say it was pleasant, but we managed it somehow,” she said. “You had to take it as you would find it.”

Though the team made decent money on the road—sometimes more than half of ticket sales—on occasion, it wasn’t enough.

“Sometimes we had to rob Peter to pay Paul, but we made it,” said Harden. “When we’d have a bad week or rain or something like that [my husband] could sort of tide it over with his business until we could make up for that loss.”

Eventually financial issues forced the Hardens to disband the team in 1940.

After another three-year period of no professional Black baseball in Atlanta, the Black Crackers came back strong. New, young players and the return of the Hardens’ leadership earned the team some strong victories and invites to join two Negro League teams.

The story of Black baseball in Atlanta from this point on is well-documented. In 1945, Jackie Robinson broke the color line by signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers. In 1949, Robinson and Roy Campanella played at Ponce de Leon Ballpark, becoming the first Black players to play in an integrated professional baseball game in the Deep South. Exactly 25 years later, Hank Aaron of the Atlanta Braves broke Babe Ruth’s legendary 714 home-run record.

As the community of Black baseball players began their new struggle for representation and success within integrated teams, the clubs of the Negro Leagues slowly lost attention and success.

Though Negro League teams such as the Atlanta Black Crackers faded into obscurity, the effects of their contributions to baseball in Atlanta can still be felt today and should continue to be acknowledged.

“We built one of the strongest organizations that has ever been in the city of Atlanta,” Kemp said. “I believe had it not been for these ball players and this team, baseball here in Atlanta during this era would have died or gone out of business.”