The American chestnut, Castanea dentata, was once one of the most important tree species in forests in the eastern United States. On wet, rich slopes in Appalachian forests, American chestnuts sometimes comprised up to 20% of tree cover and in some areas accounted for nearly a third of all trees. The chestnut was an invaluable source of lumber, and of edible nuts that fed people, livestock, and wildlife. American chestnuts also grew to great sizes and ages with some trees reported at 33 feet in circumference at the base and with lifespans of up to 600 years.

This tree that was so much a part of the American landscape for an estimated 40 million years, was made functionally extinct in forty.

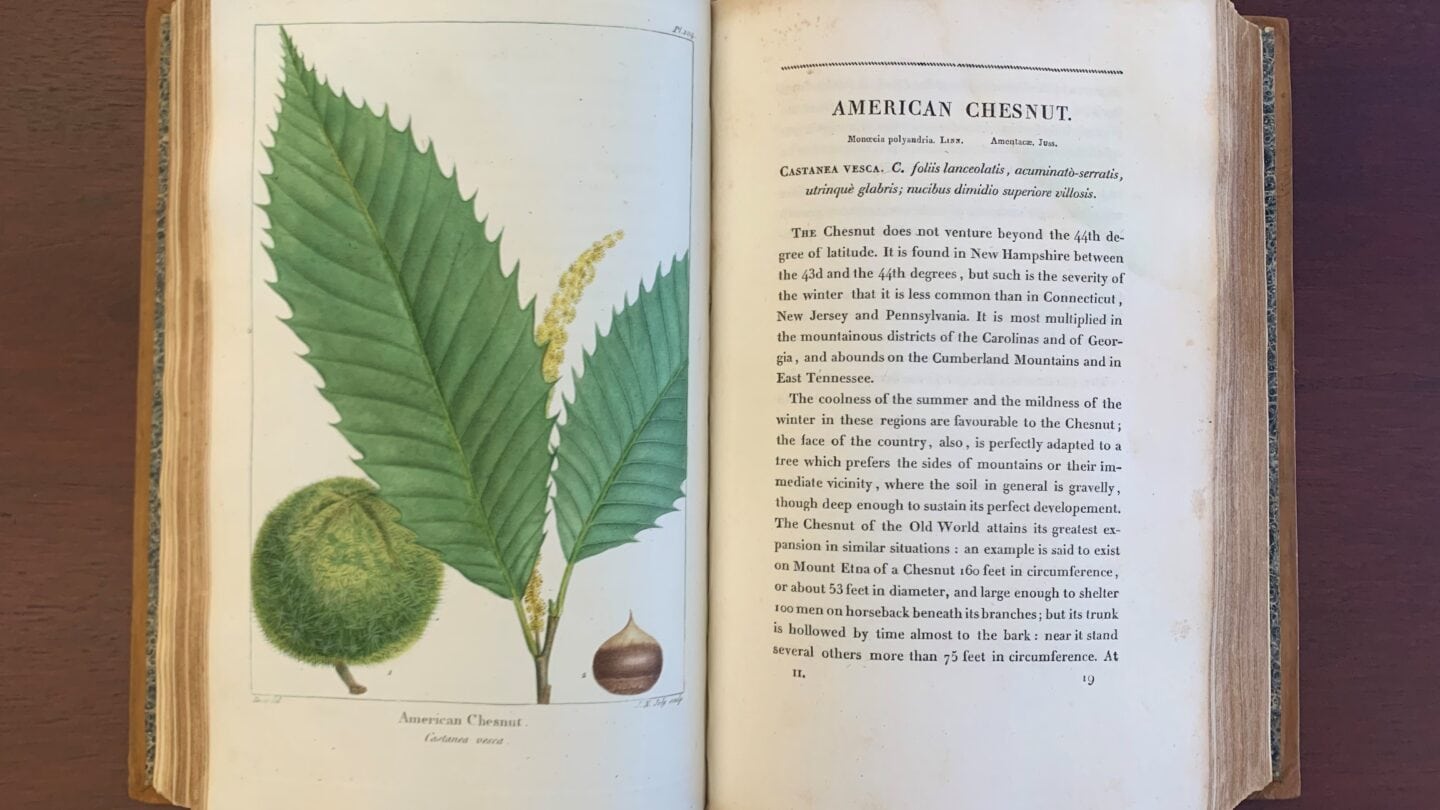

Plate 104 from François André Michaux’s The North American Sylva, or, a Description of the Forest Trees of the United States, Canada and Nova Scotia . . . V.2 (Paris: Printed by C. d’Hautel, 1819), Cherokee Garden Library Historic Collection.

Ecological Cornerstone

The American chestnut played a valuable role in the survival toolkit of Appalachian peoples, both of European and Native American ancestry. Appalachian people collected the chestnuts in vast numbers, selling them to brokers who shipped them to large cities to be roasted and sold. As well as roasting and eating the nuts themselves, Native American tribes who lived in the Appalachians, particularly the Cherokee in Georgia and the Southern Appalachians, ground them and added them to corn meal to make bread.

Chestnuts also provided food for hogs, who were left free to roam and forage in the forest and fatten themselves on chestnuts. The use by wildlife of chestnuts also benefited mountain peoples who could take advantage of the good hunting and fattened game that came along with the yearly chestnut fall.

Appalachian people used the wood widely for constructing buildings and furniture, as it was strong and rot resistant. It was also a favorite wood for fenceposts, because of its rot resistance and the ease with which it could be split. The bark and scrap wood were harvested for use in the tanning industry, as a source of tannic acid.

The speed and completeness of the loss of the American chestnut removed a significant resource from people who had depended on the trees for generations.

Blight

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a fungus known as chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica) began to spread across the eastern United States. First documented at the Bronx Zoo in 1904, chestnut blight arrived in North America on imported Japanese chestnut trees. Chinese and Japanese chestnuts evolved with chestnut blight, but for American chestnuts the fungus was entirely novel, and they had no resistance to its effects. By 1950—just 46 years after the country’s first documented case—blight had all but eliminated American chestnuts from the forests of the eastern Unites States, killing an estimated 3.5 billion trees.

Although many of the trees continue to send up new sprouts from surviving root systems, these too are killed by the blight when they reach about 20 feet in height. This is what makes them functionally extinct in the wild; though the trees are still alive, they cannot reproduce and no longer play a significant role in forest ecosystems.

The American chestnut was devastated before regular scientific investigation of its use by wildlife had taken place, but its disappearance undoubtedly has had an effect. Many different animals, including bear, deer, grouse, turkey, and other birds, took advantage of the copious quantities of nuts produced by the trees. It is believed that at least six moths depended on the American chestnut to reproduce and although several species have been rediscovered in small numbers recently, some may now be extinct.

Putting Down Roots at Atlanta History Center

Despite the widespread loss of the American chestnut, some trees survived in isolated populations or as individuals whose genetic make-up conferred some form of immunity to the blight. Beginning in the late 1980s, the American Chestnut Foundation began crossing American chestnut trees grown from the chestnuts of the few surviving trees with Chinese chestnuts, in the hope that the Chinese chestnuts would convey resistance to the chestnut blight to their American cousins. The resulting hybrids were then bred with pure American chestnuts over multiple generations to produce trees that are almost entirely American genetically, but have retained blight resistance from the Chinese trees. These hybrids are known as B3F3 American chestnuts, indicating that the hybrid has been crossed with pure American chestnuts three times. After these crosses are made, the B3F3 hybrids are deliberately infected with the chestnut blight, and only the trees that show the greatest resistance to the fungus are kept for further propagation.

With the help of Dr. Martin Cippolini, Dana Professor of Biology at Berry College, and in partnership with the Georgia Chapter of the American Chestnut Foundation, Goizueta Gardens staff at Atlanta History Center have established an orchard of trial American chestnut hybrids.

Planted in 2015, the History Center’s chestnut orchard is in Swan Woods, Atlanta History Center’s resident Piedmont forest remnant, long protected and maintained with the support of Peachtree Garden Club. The orchard is located at the western side of the meadow, downhill from Wood Cabin.

Siting American chestnuts in Swan Woods is a nod to the ecological past of the Georgia Piedmont, a region that was once home to native stands of chestnut. Although predominantly a tree of the Appalachian Mountains, the chestnut could be found on some of the higher, richer soiled slopes of the Piedmont region.

The forest that comprises Swan Woods began to grow in the decades after the Civil War, recolonizing abandoned cotton fields, and is at a stage known as secondary growth. Secondary growth is the second phase of forest growth after reestablishment of forest. Many of the initial, sun-loving trees that colonized the old cotton terraces around Swan House are reaching old age and dying, making room for the shade loving trees that have been growing beneath them for the last century and a half.

American chestnut could have been part of the initial wave of tree growth in Swan Woods, as they were known to be a fast-growing tree that could tolerate full sun. Although Atlanta is located at the southern edge of the American chestnut’s historic range, it is possible that there would have been stands in the region, especially on some of the steeper slopes and ridges along the Chattahoochee River, where many of the species of the Appalachian Mountains have their most southerly redoubts. If the blight had not extirpated American chestnuts from Georgia, they could be growing wild in Swan Woods today.

Georgia was home to some of the largest and most dominant stands of chestnuts. Northeastern Georgia, and the surrounding areas in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee, were some of the greatest strongholds for this species. The high rainfall and rich mountain soils of this region of the Appalachians was perfect habitat for the American chestnut, and it was noted historically as having a principal place in the forests of this region.

Although there have been some setbacks for the trees in the History Center orchard—a hungry deer population who spied their next meal in Swan Woods—many have reached an appreciable size over the past four years.

There are currently 18 B3F3 chestnuts growing in the orchard, with 13 of those showing promise as vigorous hybrids. With hope, the next few years should see the larger chestnuts flowering and producing nuts. Eventually, once the trees have further established themselves, the chestnut blight will be introduced to the orchard so that the inherited resistance of the hybrid chestnuts planted at the History Center can be evaluated. Once resistance is confirmed, or not, nuts from the resistant hybrids can be germinated and grown into, hopefully, resistant trees.

With a thriving orchard of blight resistant chestnuts, Atlanta History Center can begin distributing nuts and trees to establish more nurseries at other institutions, playing a role in the revival of one of the great American tree species and helping the History Center to tell the story of the landscape history of Atlanta, Georgia, and the Southeast.

Goizueta Gardens at Atlanta History Center offer 33 acres to explore the variety of landscapes that have shaped our city’s history. Comprising nine distinct gardens, Goizueta Gardens contains preserved woodland, diverse plant collections, and heritage-breed animals. Through the American Chestnut Foundation partnership, our sustainability practices, and other initiatives, we encourage our guests to study the ecological history of our city and take part in its next chapter. Whether they’re among the swaying native grasses of our Entrance Gardens or walking through rows of edible plants at Smith Farm, visitors to Goizueta Gardens find themselves steeped in the historic landscapes that make our city and its history unique.