Cuban prisoners on the roof of the U.S. penitentiary in Atlanta during the riot. (Southline Press Photographs, VIS 158, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Something about November 23, 1987, seemed amiss to Alfredo Villoch. A government accountant at the Atlanta federal penitentiary, Villoch was accustomed to seeing and hearing the nearly 1,400 Cuban prisoners noisily go about their daily routines of making gloves, brooms, canvas bags, and other goods for the U.S. government. But November 23 was different. The Cubans were eerily quiet.

"Usually, the Cubans were very loud, like a beehive," he told the Creative Loafing in an interview. "But when I walked through the cellblock that morning, you could've heard a pin drop and I thought, 'Uh, oh.'"

Villoch’s suspicions were realized when around 11 a.m. he heard shouting and people making loud noises in the prison dining facility. A riot had begun. Villoch and his colleagues locked themselves in their office. The locked door was only a minor inconvenience to the agitators. They wanted Villoch and his associates, and they didn’t rest until they had them. The rioters used their brute strength to assault the office door. As the door was about to come off its hinges and give way, Villoch opened it and in rushed a group of Cuban inmates. In that instant, the tables had turned. The Cuban prisoners told Villoch and the other penitentiary staffers that they were now being detained.

Prison employee Phil Little walks in front of a wall featuring messages from Cuban inmates at the Atlanta federal penitentiary during a tour of the prison yard after a riot that began on November 10, 1987. (Frank Niemeir, AJCP141-033c, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library)

The riot was a response to the U.S. State Department’s November 10, 1987, announcement that the Cuban government had agreed to take back up to 2,500 Cuban citizens imprisoned at the Atlanta facility.

In 1980, Fidel Castro had sanctioned a mass exodus of Cubans when he opened the port of Mariel to people who wanted to leave the country.

More than 125,000 Cubans flocked to the U.S. when President Jimmy Carter said that the U.S. would embrace its history as a nation of refugees and “continue to provide an open heart and open arms to refugees seeking freedom from Communist domination and from the economic deprivation brought about by Fidel Castro and his government."

The refugees were nicknamed Marielitos because they fled Cuba via Mariel, the closest port to the U.S. Those refugees came to the U.S. without legal status.

Marielitos were seen as less respectable than Cubans who had immigrated previously. Though most of the Marielitos who arrived in the U.S. had been law-abiding citizens in Cuba, after their arrival, they were often portrayed in popular culture through larger-than-life characters such as those in the 1983 film Scarface, as rough and tumble, criminally minded Cubans.

Part of this perception comes from the fact that Castro reportedly opened prisons and mental institutions and encouraged criminals and the mentally ill to leave the island during the boatlift. According to the New York Times, the stereotype may also be rooted in prejudice, since as many as 40% of those who left during the Mariel Boatlift were Cubans of African descent, while others were being persecuted for their political beliefs, religious convictions, or sexual orientation.

When the Immigration and Naturalization Services processed Cuban Marielito petitions for naturalization, many were classed as “excludable aliens.” Marielitos who committed crimes in the U.S. while they were awaiting an INS decision on their petition for naturalization were rounded up and imprisoned by the federal government. Often, they had already served time for their offense in local or state correctional facilities.

Up to 37% of the 3,800 Marielitos accused of criminal acts were incarcerated at the Atlanta federal penitentiary alongside a few hundred Americans. The facility had been designed to hold 1,500 prisoners and was slated to close until the U.S. government selected it to house the Cubans.

About two weeks after the state department brokered the deal with Castro to send the incarcerated Cubans back to Cuba, chaos ensued, and all hell broke loose inside the penitentiary. The Cuban nationals went on to take more than 100 prison staffers captive and hold them hostage for more than a week while attempting to negotiate a plan to halt their return to Cuba.

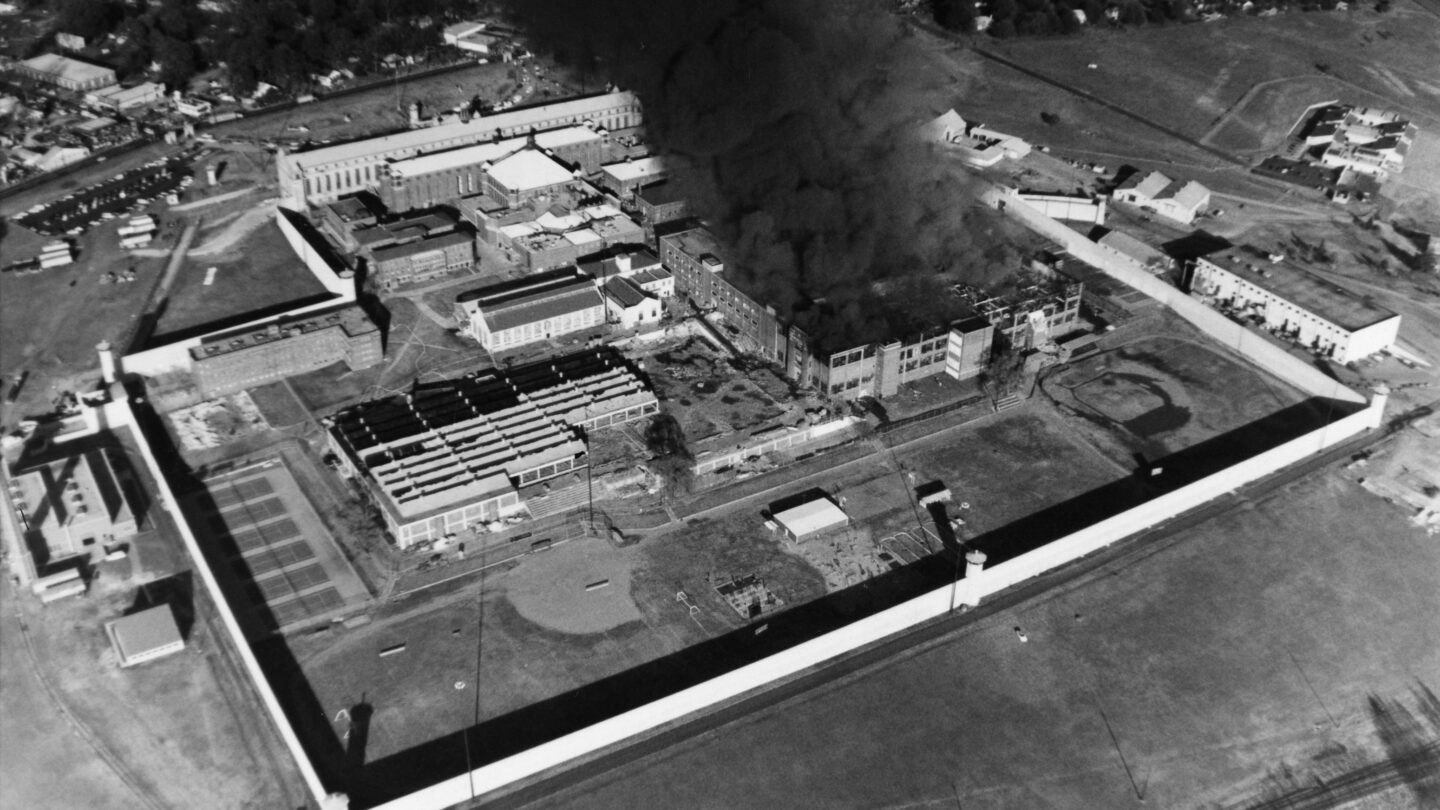

Once word spread of the hostile takeover inside the prison, things became just as chaotic on the outside. Atlanta police closed off McDonough Boulevard, the street in front of the prison’s main gate, onlookers, news crews, inmates' family members, and political leaders jammed the sidewalks near the prison, while firefighters in helicopters flew overhead dropping massive amounts of water to extinguish a blaze that was consuming parts of the prison complex.

The burning Atlanta federal penitentiary during the Cuban prison riot, 1987. (AJCP141-033b, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library)

After negotiations during an 11-day standoff, the Cuban prisoners agreed on December 3 to end the uprising. Federal officials escorted rioters out of the prison one-at-a-time before placing them in restraints and transferring them to other facilities.

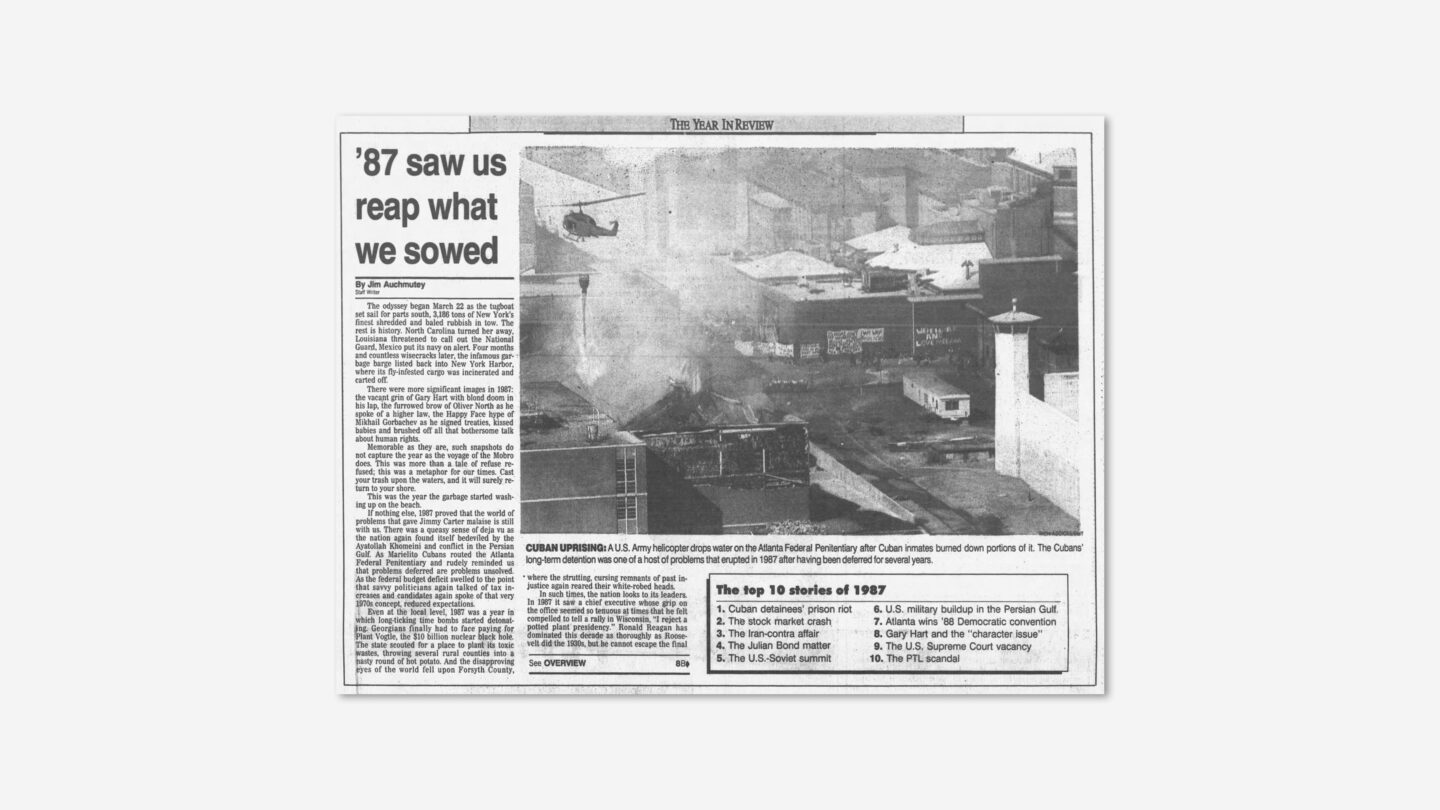

Later, as promised, the federal government delayed deportations and gave Cubans who were in federal custody new immigration status hearings. According to the Atlanta Journal Constitution, about 1,000 detainees were sent back to Cuba and the rest were released during the following years. Though most people today are not familiar with the event, the riot was the top story in Atlanta Constitution’s 1987 year-in-review, eclipsing the Iran-Contra political affair, a stock market crash, televangelist Jim Bakker and the PTL Club financial scandal, and a military build-up in the Persian Gulf.

The riot holds the record for the longest prison standoff in U.S. history. It led the Federal Bureau of Prisons to institute sweeping procedural changes and modify its emergency response plan. During the event, prisoners set fire to a warehouse on the premises and caused more than $35 million in damage to the prison complex. One inmate died during a shootout with a prison guard. Prison staffers, though they reported that they were treated well during their captivity, were left with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Even Villoch, who told Creative Loafing that he isn’t “haunted by his experience,” didn’t remain on the job for long after the hostage situation. He continued to work at the facility for a few months before he transferred to another federal government position.

"Those 11 days as a hostage was the worst time of my life," he said of the ordeal. "But I don't mind talking about it. Talking helps me be at peace with it."