Opening of Southern Crossroads Festival in Centennial Olympic Park | Stephanie Klein-Davis, photographer, Atlanta, July 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Though today’s Olympic Games promote excellence in sport, that hasn’t always been the case. In the early 20th century, participants could win gold medals for art and literature alongside their athletic counterparts. Though the art competitions were eliminated after 1948, their legacy remains in the form of a host city’s brand and marketing designs, the artistic programs of opening and closing ceremonies, as well as robust associated arts festivals and cultural events coordinated to accompany the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Throughout the late-19th century and early-20th century, Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, praised the importance of balancing mind, body, and spirit through education and culture as well as physical sport. This guiding philosophy supported the development of an artistic component of the Olympic Games. Though separate from the sporting program, it was important to the spirit of the Games as a whole.

Since that time, the role of artists and art administrators has changed, and the presence of art has deepened. Support for art and culture in association with the Olympic Games is now integral to how host cities endeavor to make long-term change to the identity of their cities. The role of art and culture at the ’96 Games fits into the trajectory of art in modern Olympic Games. It also expedited the growth of Atlanta’s creative community. Infusions made during the 1990s had a lasting impact on our city’s organizations, businesses, and art scene.

From Medals to Festivals

From 1912 to 1948, the Olympic Games held art competitions. Artists submitted work of art inspired by sport under a range of categories, including architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and literature. They were judged and awarded medals just like their peers in the athletic competitions. Over the years, organizers debated whether the competition should continue to require a sport theme.

By 1928, categories were split into new subcategories: architecture received a town planning category; literature split into dramatic, lyric, and epic; sculpture became statues and reliefs; painting subdivided to include drawings and graphic arts; and music later splintered into five separate competitions. This made consistency from year to year a challenge. Counter to the Games’ spirt of international unity, Europeans and Americans dominated the judging pool and winners circle, leaving little room for art or artists from other parts of the world.

The 1936 Games in Berlin hosted by the Nazi regime were a notable point of reference for the development of artistic programming and cultural productions outside of the competitions. The regime introduced new rituals for the Games, including the torch relay, and connected larger cultural programs to the event as propaganda for the state. One output of this was Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympia.

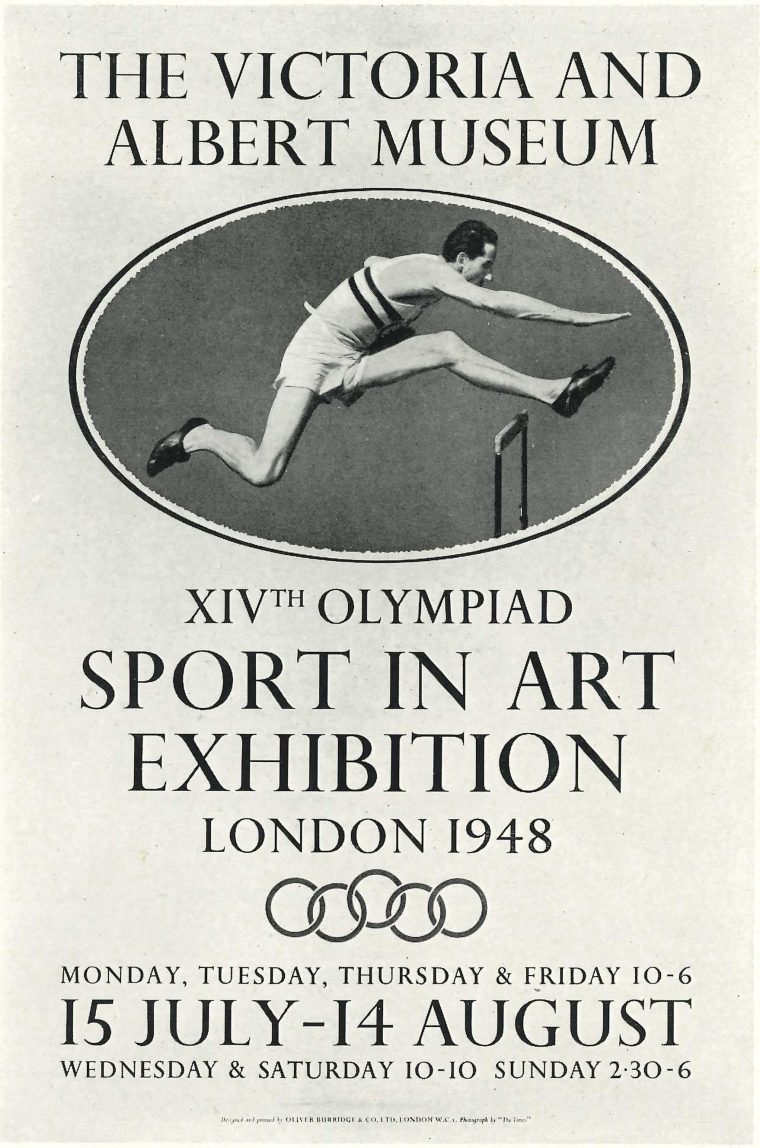

“Sport in Art Exhibition” | Exhibition poster | Victoria and Albert Museum London: XIV Olympiad Committee, 1948 | Purchase with funds in support of the exhibition, 2020

The expansions made to art and culture programs in 1936 were maintained in the Olympic Games after World War II. The Games in London in 1948 were the last to host art competitions. Yet, by 1952, organizers in Helsinki hosted a series of exhibitions and art and culture programs instead. The Games in Melbourne in 1956 were the first to host a full-scale art festival, including events for visual arts, literature, music, and drama.

In the following decades, the length of festivals or art programs fluctuated, and themes changed from year to year, but the initiatives continued to expand. By the 1980s, ideas of urban regeneration through expansion of art and cultural programming took hold in cities across the world, and the Olympic and Paralympic Games aligned with these efforts.

Organizers of the 1992 Games in Barcelona expanded past templates for art festivals, planning the first Cultural Olympiad. The Olympiad filled the four years between the close of Games in Seoul in 1988 and the opening of the 1992 Games with festivals, events, exhibitions, and programs. The activities contributed to organizers’ mission to shape Barcelona’s cultural tourism industry and international profile.

The Arts in Atlanta

Night view of the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, 1969 | Atlanta History Photograph Collection, VIS 170.2616.001

Atlanta continued the Cultural Olympiad precedent, planning a vast catalog of art and cultural offerings that spanned multiple years and making investments in local museums and arts organizations. The initiatives were built on a longstanding cultural scene in Atlanta. Supported by the colleges at Atlanta University Center—referred to by the Smithsonian American Art Museum as the “L’Ecole de Beaux Arts of the Black South”—Black visual artists comprised a community that had been thriving since the early 1900s.

Atlanta’s Memorial Art Center, now Woodruff Arts Center, provided the city with a major institutional hub for the arts. The center grew in the 1960s, supported by donations honoring those who died in the 1962 Orly plane crash, as well as anonymous funding from Robert Woodruff, for whom the art center is now named.

In the 1970s, Mayor Maynard Jackson’s administration supported the growth of a grassroots arts scene through artist funding programs, community organization seed money, and the development of a new Department of Cultural Affairs. Large and small organizations throughout Atlanta, and both emerging and established artists working in the city at that time found involvement in the Olympic-stimulated art scene of the 1990s. Atlanta’s Cultural Olympiad brought new funding and resources to these facets of the city’s art and cultural industry, tying them together for shared initiatives before, during, and after the summer of ’96.

Centennial Scope

The aim of artistic programming for the ’96 Games was to present the American South to the world and invite the world to the region. The resulting programs mixed traditions, genres, and disciplines to achieve a multicultural mission. Cultural Olympiad organizers partnered with existing Atlanta-area art, culture, and humanities organizations in different ways, including curating programs, arranging locations, and attracting attention. This partnership offered the rare opportunity to create projects outside the realm of possibility for local institutions with limited budgets. The scope included festivals, public art installations, and an increased variety of offerings during the Games.

Performance during “Mexico: A Cultural Tapestry” festival | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, September–October 1993 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Between the Games in Barcelona in 1992 and the summer of ’96, Atlanta’s Cultural Olympiad produced several largescale festivals. Olympic Winterland: Encounters with Norwegian Cultures corresponded with the Winter Games in Lillehammer, Norway. Mexico: A Cultural Tapestry and Celebrate Africa filled stages and galleries, commissioned new artwork, and brought a range of artists to the city. 100 Years of World Cinema focused on film. A multi-day gathering of Nobel Laureates of Literature brought writing to the forefront, assembling literary greats from across the world in Atlanta. The list included Toni Morrison (U.S.), Derek Walcott (Saint Lucia), Kenzaburō Ōe (Japan), Octavio Paz (Mexico), and Camilo José Cela (Spain), among others.

“Celebrate Africa!” |Atlanta: Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games and National Black Arts Festival, 1994 | Association Subject Files – National Black Arts Festival, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The Celebrate Africa festival in the summer of 1994 was developed through a partnership between the Cultural Olympiad organizers and Atlanta’s National Black Arts Festival. Established by Fulton County Commissioner Dr. Michael Lomax, the first National Black Arts Festival (NBAF) was held in 1988, a product of Atlanta’s growing Black arts scene. The star-studded lineup of Black artists drew large crowds in Atlanta and quickly developed a reputation.

One of NBAF’s original artistic directors, Stephanie Hughley, departed the organization to lead the Cultural Olympiad’s theater and dance productions. She also forged the partnership that resulted in Celebrate Africa. In the summer of ’96, NBAF operated its own festival; there was little cross-promotion or funding between the two festivals. The heightened spotlight the Games brought to Atlanta that summer made separate events difficult, with attention primarily on the Olympic endeavor.

The cultural initiatives of the ’96 Games also focused on the fabric of the city, including a push to fill Atlanta’s parks, medians, and landscapes with public art. Consultants to the Cultural Olympiad and city improvement committees recommended using public art to create a recognizable symbol for the city of Atlanta. In the end, the committees selected 100 works of art to be installed across Atlanta in time for the Games. Curators, art critics, and art administrators from the Atlanta area came together with Cultural Olympiad and Corporation for Olympic Development in Atlanta staff to curate and select the artists for this major undertaking. Some artists were specifically commissioned, and others applied to a public call for ideas.

Siah Armajani presenting his Cauldron designs | Marilyn Suriani, photographer, Atlanta, March 24, 1994 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Perhaps the most recognizable work of public art to come from this movement is Atlanta’s Olympic Cauldron. Originally connected to Centennial Olympic Stadium, it was erected to hold the Olympic and Paralympic flames for the duration of the Games. The ’96 Games marked the first time a cauldron was created by an artist rather than an engineer or architect.

Cultural Olympiad organizers commissioned Iranian American artist Siah Armajani. Armajani was known for his works of public art that exist at the intersection of sculpture and architecture. He created a complicated structure that comprised a bridge and stair-wrapped tower for Atlanta’s cauldron. The design ultimately posed issues for television broadcast needs since it limited access the fire basin at the top. Disagreements and communication gaps between the artist and Atlanta’s Olympic organizers resulted in Armajani writing the design out of his oeuvre. The cauldron was moved down the street after the Games when the stadium was converted into Turner Field for the Braves baseball team. Armajani passed away in August 2020. His work remains a focal point in Summerhill.

Atlanta Start by Cristóbal Gabarrón | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, circa June 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Other works of public art include Xavier Medina-Campeny’s Homage to King in Old Fourth Ward, and downtown’s Folk Art Park. The collection of works installed in advance of the Games have been moved and conserved over the years. Many are documented though the Office of Cultural Affairs.

Olympian Alice Coachman points to a photograph of herself in The Olympic Woman exhibition, Alumni Hall, Georgia State University | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, circa June 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

With Games time approaching in the summer of ’96, the number of art and cultural events increased dramatically. The Olympic Arts Festival offered nearly 200 ticketed events, including more than 20 exhibitions in local institutions, museums, and gallery spaces, and invited more than 3,000 artists to Atlanta during the two weeks of the Games. There were numerous free events on the schedule as well, including a daily series in Centennial Olympic Park, called Southern Crossroads.

The festival’s budget was approximately $24 million. Southern Crossroads presented multidisciplinary events, such as bluegrass or zydeco concerts, Appalachian clogging lessons, and Southern food selections. AT&T’s Global Olympic Village stage in the park featured nightly concerts by popular musicians, including Ray Charles and Travis Tritt. Colleges and galleries across the metro area produced educational programs and exhibitions. Many of Atlanta’s museums placed their names on the tourism map with high profile programs.

AT&T Global Olympic Village stage in Centennial Olympic Park | Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, circa July 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Rings: Five Passions in World Art was one of the most highly publicized events of the Olympic Arts Festival. The major art exhibition at the High Museum of Art was curated by J. Carter Brown, recently retired director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The concept for the exhibition used the framework of the five Olympic rings to arrange a broad selection of multicultural art pieces, including highlights of sculpture and painting from the National Gallery, as well as textbook pieces from museums across the world.

These were organized within five categories of emotion: love, anguish, awe, triumph, and joy. With Brown’s curatorial profile, the exhibition developed a cutting-edge catalog available on CD-ROM and garnered a broad range of publicity, which helped to put the High Museum of Art on the U.S. cultural map. Many art critics, however, commented on the exhibition’s blockbuster status, preferring to highlight more authentic Southern offerings on other parts of the Festival schedule.

B-roll footage of Rings: Five Passions in World Art | Unidentified videographer, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The High Museum exhibition stood at odds with another major exhibition of the Games: Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South. Souls Grown Deep was a brainchild of local Atlanta collector William S. Arnett, who developed a selection of folk and self-taught artwork from vanguard Black artists across the South. The potential exhibition project was originally discussed as being presented at the High Museum of Art until Brown’s project took precedence.

The Carlos Museum at Emory University then partnered with Arnett to present an exhibition of Thornton Dial’s work at Emory and Souls Grown Deep at City Hall East (now Ponce City Market) for Olympic audiences. The landmark exhibition reinvigorated Arnett’s work and directed attention to the collection, receiving glowing reviews. The Souls Grown Deep Foundation continues to operate today, funding work with their catalogue of artists and gifting major works to museums across the country.

B-roll footage of Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South | Unidentified videographer, City Hall East, Atlanta, Summer 1996 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Olympic Influence

The ’96 Games prompted and inspired cultural activity well beyond the schedule of events produced by Olympic organizers and partnering institutions. Communities across Atlanta took the opportunity to showcase their city to the world in different ways. Artists and organizations formed new initiatives, aligned projects, and inspired activities. Artistic reactions to the Games rippled throughout Atlanta’s cultural scene for decades, feeding everything from hip hop culture to the restaurant industry.

A hub run by and for the LGBTQ+ community opened at Center Stage Theatre for the duration of the Games. The Gay and Lesbian Visitors’ Center served as a welcoming center to LGBTQ+ tourists coming to Atlanta for the Games. The Center also commissioned and presented a wide range of programs, including plays and art exhibitions involving well-known artists and giving a start to emerging artists in Atlanta’s LGBTQ+ community.

Center Stage: The Gay and Lesbian Visitor’s Center | Informational pamphlet | Courtesy Georgia State University Library, Maria Helena Dolan Papers

For the first time ever, the Paralympic Games featured a “Cultural Paralympiad” in Atlanta. This new art and cultural festival highlighted the talents and experience of disabled people and disabled artists. The programs were funded by state and local arts and humanities agencies, along with disability services organizations. Events included dance, theater, and art exhibitions. In more recent Games, such as the 2012 Games in London and plans for the 2020 Games in Tokyo (postponed to 2021), disability arts received greater recognition in the art programs, creating greater connection between the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

1996 Cultural Paralympiad: Calendar of Events | Oakville, Ontario, Canada: Disability Today Publishing Group, 1996 | 1996 Olympic Games Subject Files – Paralympics, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The investment in art and culture in advance of the ’96 Games shaped the city we know today. Administrators, curators, and artists added to their professional experience; artists outside the Olympic circle responded to the activity; dream projects, funded by Olympic dollars, catapulted some organizations to greater recognition and visibility; projects and artworks created have been logged into art history; and the schedule of offerings influenced how the Games since ’96 conceived of artistic programming.

Additional. Resources.

- MAP: City of Atlanta’s Public Art Collection

- Garcia, Beatriz. “One Hundred Years of Cultural Programming within the Olympic Games (1912–2012): Origins, Evolution and Projections.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 14, no. 4 (November 2008): 361–76.

- When the Olympics Gave Out Medals for Art | Smithsonian Mag

- Atlanta Remembers: The Atlanta Olympic Cultural Olympiad, a partnership between ArtsATL and WABE | ArtsATL

- Art and Activism in 1970s Atlanta | Atlanta Studies

- An Olympic-Sized Festival of Culture | Orlando Sentinel

- Barcelona Counts Up Olympic Side Effect | New York Times

- Souls Grown Deep and the Cultural Politics of the Atlanta Olympics | Radical History Review

- Atlanta Gay and Lesbian Visitor’s Center | Georgia State University Library Exhibits

- Japan will deliver big during Tokyo 2020 Cultural Olympiad, London Games official says | The Japan Times

Major support of this exhibition has been generously provided by the James M. Cox Foundation, Marine and John A. Fentener van Vlissingen, Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, The Coca-Cola Company, Martha and Billy Payne, The UPS Foundation, Martie and Dennis Zakas, and The Rich Foundation.

We invite you to learn more about the impact of the Cultural Olympiad in Atlanta ‘96: Shaping an Olympic and Paralympic City, now open.