Elizabeth McDuffie, circa 1933. Elizabeth and Irvin McDuffie Papers, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

When film producer David O. Selznick embarked on his adaptation of Margaret Mitchell’s novel, “Gone with the Wind,” he aspired to present an authentic portrayal of Mitchell’s characters, particularly the leads.

After 1,400 screen tests, Selznick chose Vivien Leigh to play Scarlett O’Hara, the headstrong and cunning Southern belle whose relentless determination, fierce survival instinct, and tumultuous love life shape her journey through the Civil War and Reconstruction periods.

For Rhett Butler, the complex, roguish, and astute anti-hero whose charm, strategic wit, and unapologetic pursuit of self-interest define him, Selznick went with his first choice Clark Gable, the “King of Hollywood.”

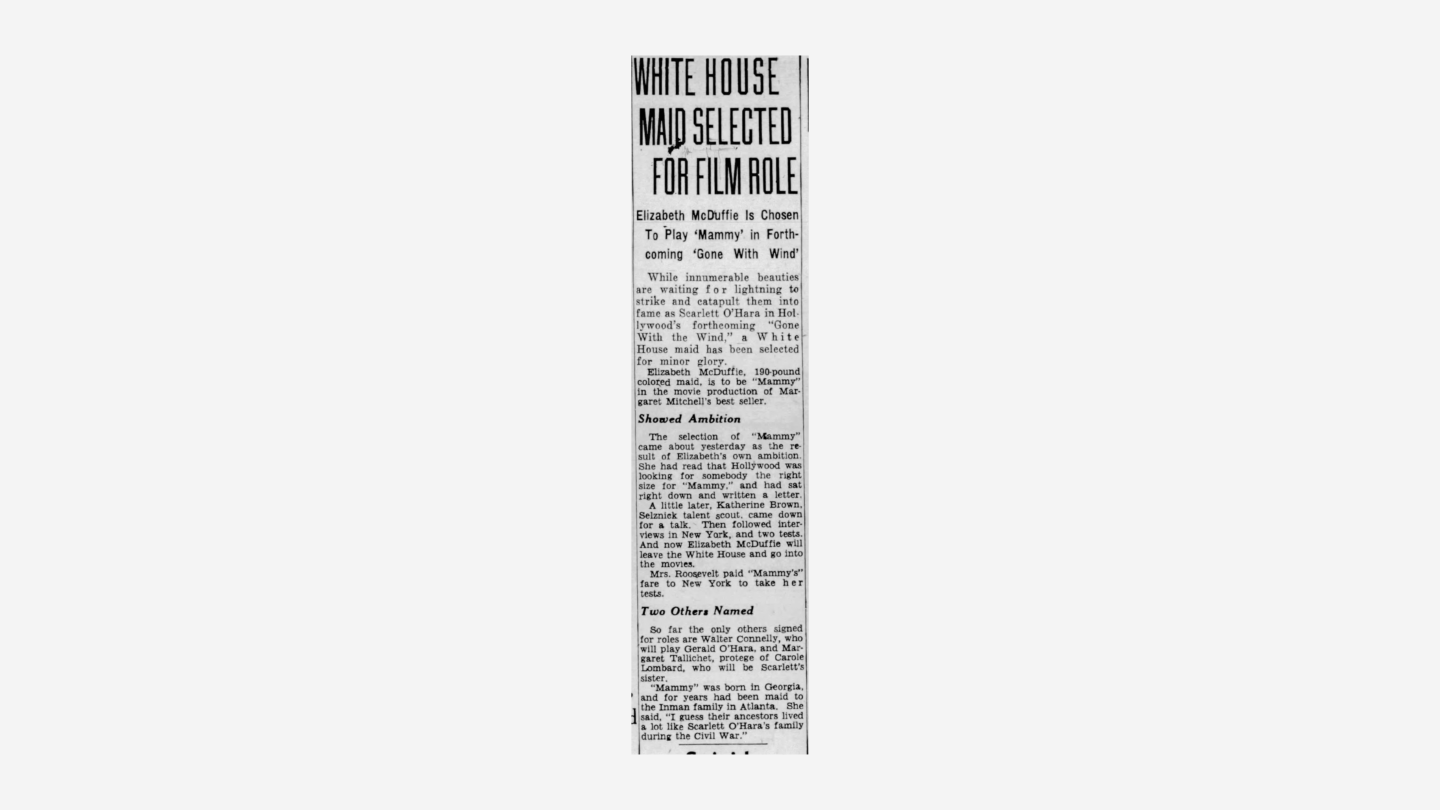

However, there is little information regarding the casting of Mammy, O’Hara’s enslaved nursemaid and housekeeper, a central figure in the novel because of her loyalty, outspoken personality, and strong moral compass.

Though the role eventually went to Hattie McDaniel, an actress and radio personality, who would become the first Black woman to win an Academy Award, another woman, Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie, was initially thought to be cast. Initial reports, such as an article from the Washington Herald, said that Selznick chose McDuffie for the role because of her “size” and “ambition.”

Elizabeth McDuffie dressed as a “mammy” figure. January 7, 1938, “Cooks for President,” Shelby County Democrat

McDuffie, a personal cook, maid, and informal advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor, auditioned for the role and was columnist Walter Winchell’s favorite choice. She was also Margaret Mitchell’s choice for the role.

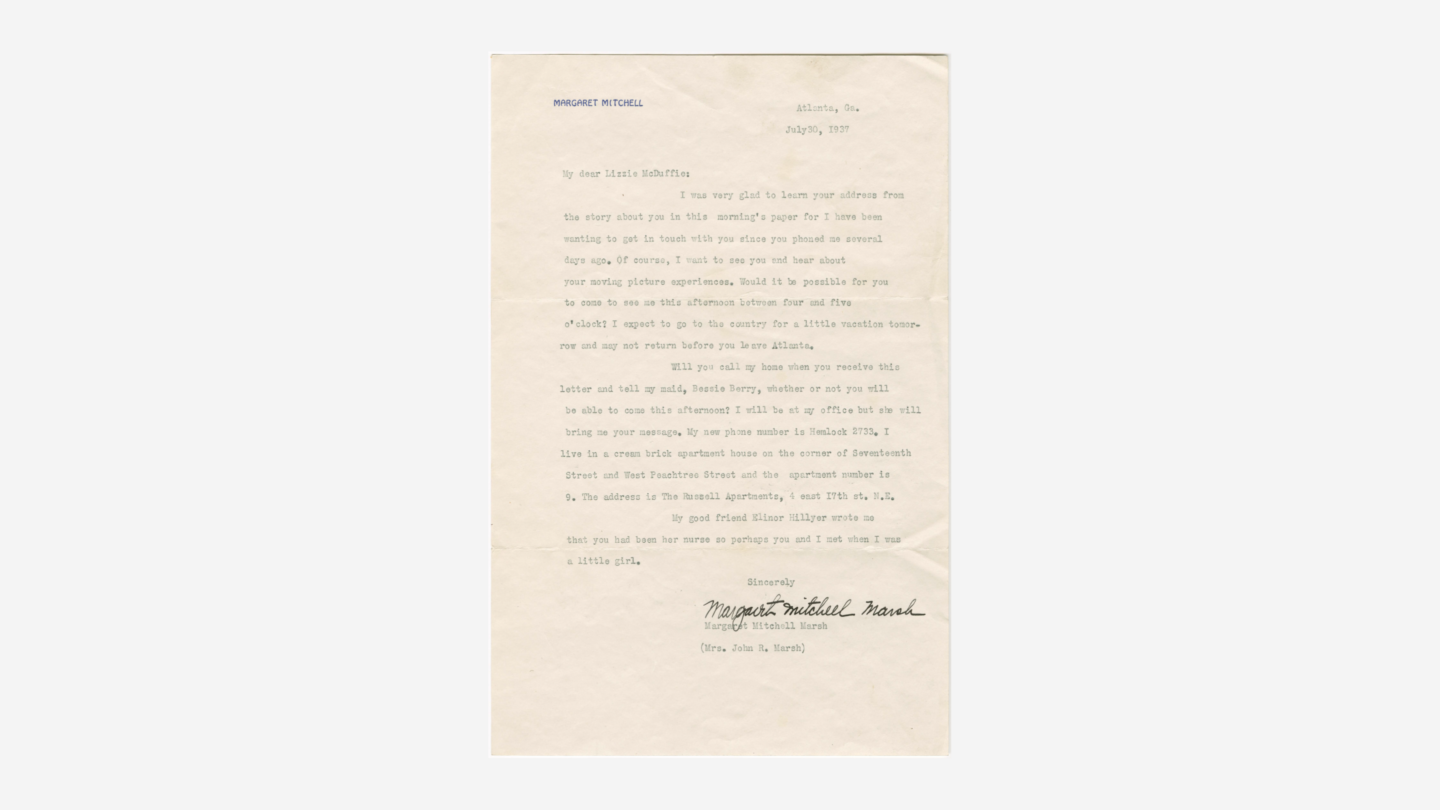

Mitchell and McDuffie became acquainted after Mitchell wrote McDuffie in July 1937. In her letter, Mitchell asked McDuffie to visit her because she wanted to talk to her about her acting experience.

“I was very glad to learn your address from the story about you in this morning’s paper for I have been wanting to get in touch with you since you phoned me several days ago,” she wrote. “Of course, I want to see you and hear about your moving picture experiences. Would it be possible for you to come to see me this afternoon between four and five o’ clock? I expect to go to the country for a little vacation tomorrow and may not return before you leave Atlanta.

While McDuffie’s desire to portray Mammy in 1938’s Gone With the Wind, went unfulfilled, her role as a domestic maid and her close association with the Roosevelts accorded her the platform to become an early and successful advocate for equal rights, civil rights, and workers’ rights for African Americans.

Born in Covington, Georgia, in 1881 to formerly enslaved parents, McDuffie had a passion for theater from a young age. In her youth, she developed programs and wrote plays while attending Summerhill School in Atlanta. Besides assisting in the production of religious plays at churches and directing children’s plays, she also undertook public speaking lessons.

Irvin and Elizabeth McDuffie, July 1931. Elizabeth and Irvin McDuffie Papers, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

Following high school, McDuffie earned a bachelor’s degree from Morris Brown College. However, despite her qualifications and experience, the early 20th-century South denied many opportunities to her as a Black woman. Consequently, she found work as a maid for affluent Atlantans.

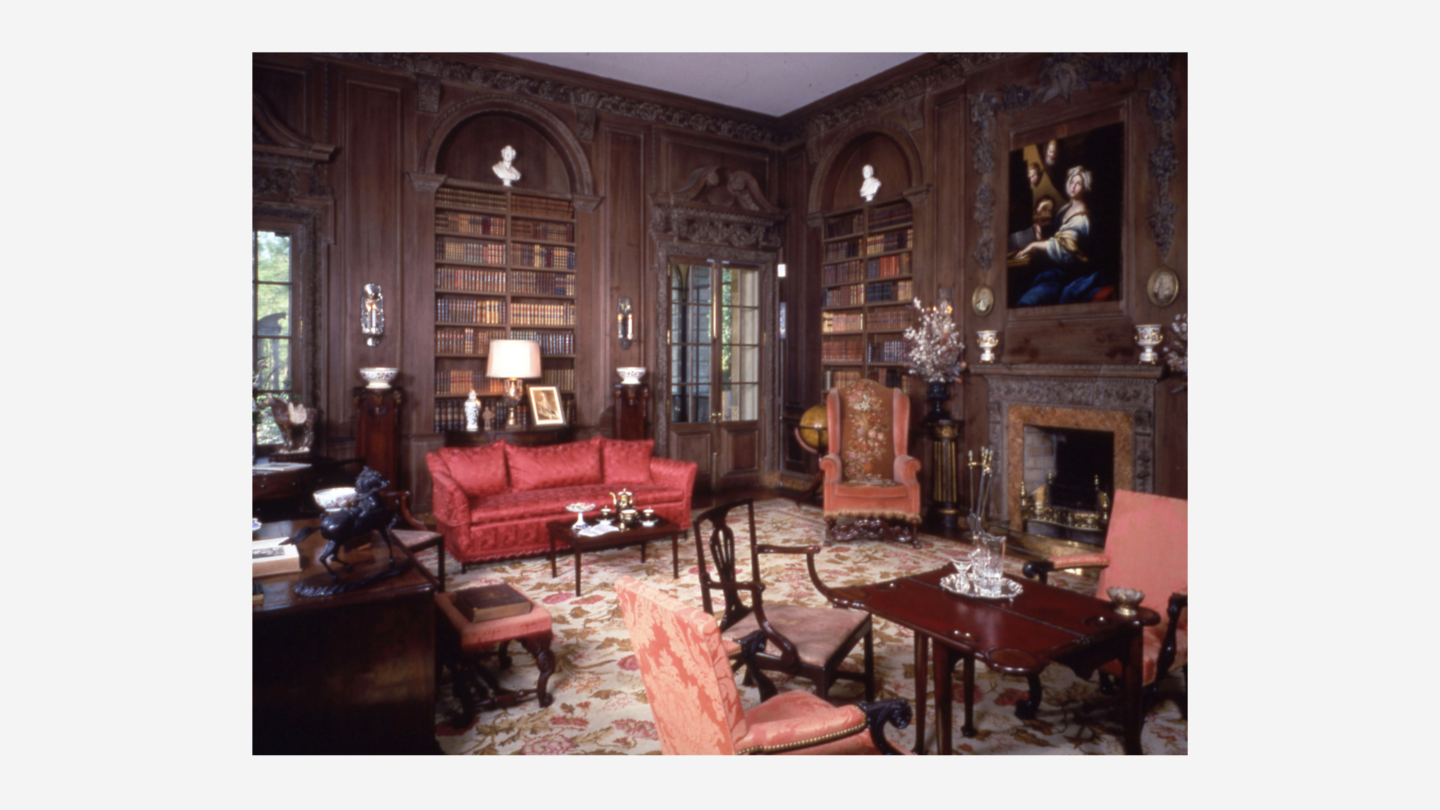

Eventually, McDuffie went to work for Edward and Emily Inman and their two children, Hugh and Edward Jr. She served the family for more than three decades.

McDuffie still worked for the Inmans when they relocated to a new residence designed by architect Philip Trammell Shutze in 1928, an estate currently known as the Swan House, until 1933, when President Roosevelt offered her a job.

McDuffie had been introduced to President Roosevelt when her husband, Irvin, became FDR’s valet in 1927.

While in the Roosevelt White House, McDuffie decided to become FDR’s “SASOCPA,” or “self-appointed secretary on colored people’s affairs.” She had lived through the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906, and one of her friends was among the estimated 25 to 40 African Americans killed. This harrowing experience ignited her passion for racial equality and African American workers’ rights.

“My job at the White House became more than just a job; it became a small crusade, perhaps because I remembered that fearful march of my people from South Atlanta,” McDuffie said.

As the president’s trusted informal advisor, McDuffie facilitated communication between FDR and Black civil rights activists such as Edgar G. Brown of the Civilian Conservation Corps, Mary McLeod Bethune of the National Youth Administration, and Walter White, the NAACP’s leader.

Elizabeth McDuffie seated at a desk, circa 1960, Elizabeth and Irvin McDuffie Papers, Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library

White, an Atlanta native, had also witnessed the 1906 Race Massacre. Through McDuffie’s back-channel efforts, White brought to President Roosevelt’s attention the unjust incarceration of three African American World War I veterans implicated in the Houston Riots of 1917, which began as a protest against police brutality. McDuffie supplied Roosevelt with additional details and context on the riot, which led to a pardon for the three prisoners.

McDuffie also actively campaigned for President Roosevelt in the 1936 and 1940 presidential elections. In 1938, McDuffie voiced her support for thousands of Black women protesting the New Deal programs’ limitations, barring them from earning living wages. She helped organize the United Government Employees—a union representing lower-paid workers—and served as its secretary.

McDuffie died on November 27, 1966, and was buried at Atlanta’s Southview Cemetery.