The Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport is among the world’s busiest, rivaling Dubai International Airport and London’s Heathrow Airport. Stretching over 4,700 acres, or about seven square miles, this complex has come a long way from its humble beginnings. Its origin traces back to a modest two-mile racetrack funded by Asa Candler in Hapeville. With Candler’s initial investment, the airport’s transformative journey began. Over the decades, other visionaries have also tirelessly worked to elevate Atlanta’s standing as an airport hub, aspiring to dominate the Southern skies and command recognition on the global stage.

Asa Griggs Candler, undated. Wikimedia Commons

Asa Griggs Candler (1851–1929)

Asa Griggs Candler was a successful Atlanta businessman, founder of the Coca-Cola Company, and Atlanta’s mayor from 1917 to 1919. Born in Villa Rica, Georgia, in 1851, he began his career as a pharmacist. After establishing himself as a successful patent medicine manufacturer, Candler bought the rights to Coca-Cola from John Pemberton in 1888. After achieving millionaire status with Coca-Cola, Candler delved into philanthropy, real estate, and banking in his later years.

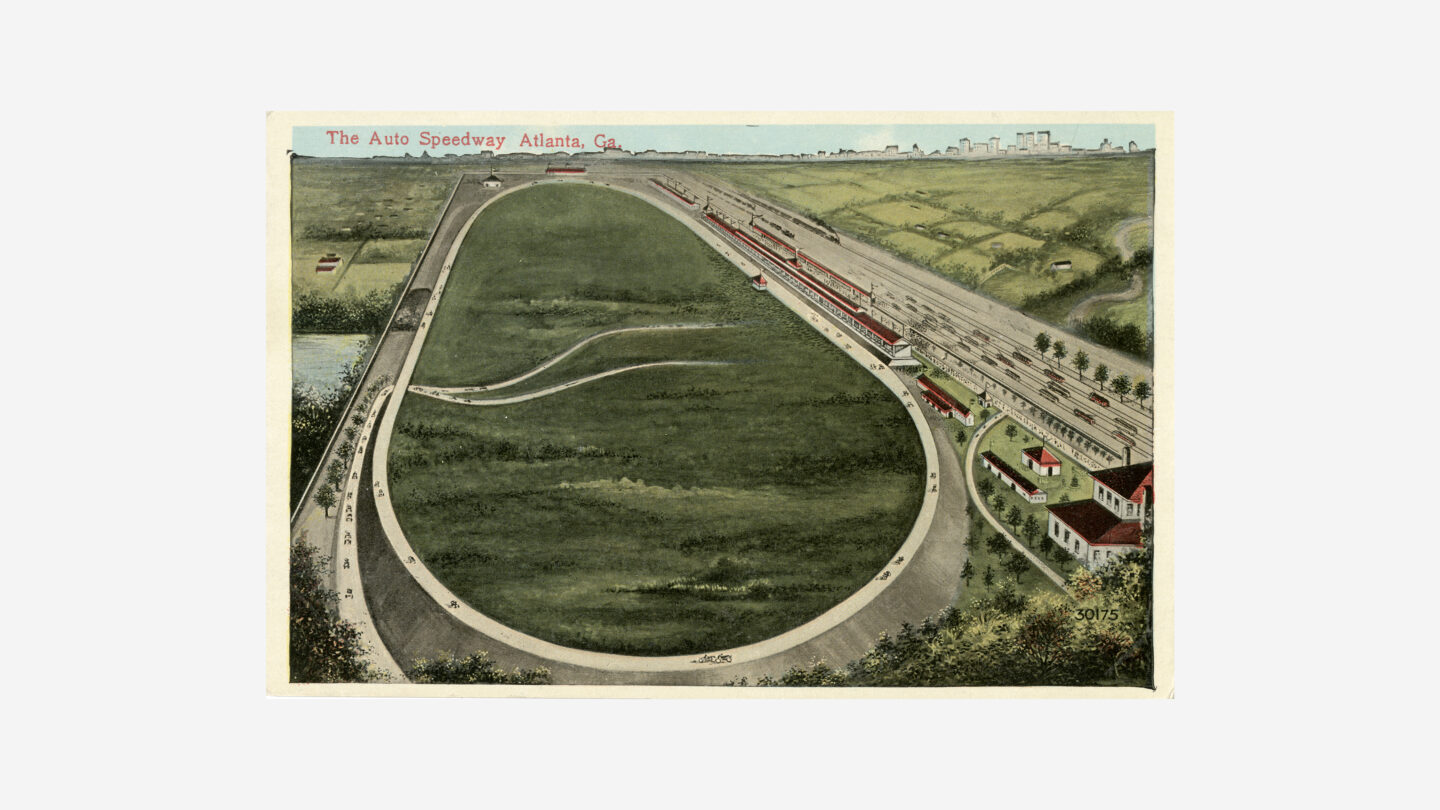

Candler’s wide-ranging interests and substantial wealth led him to propose the construction of a top-tier racetrack in Atlanta. He named it the Atlanta Speedway. The racetrack was built in 1909. Candler Sr. appointed his son, Asa Candler Jr., as president of the Atlanta Automobile Association, which Candler Sr. established for the speedway’s operation. Candler Jr. was an enthusiast of both automobiles and aviation, participating in local and national air races.

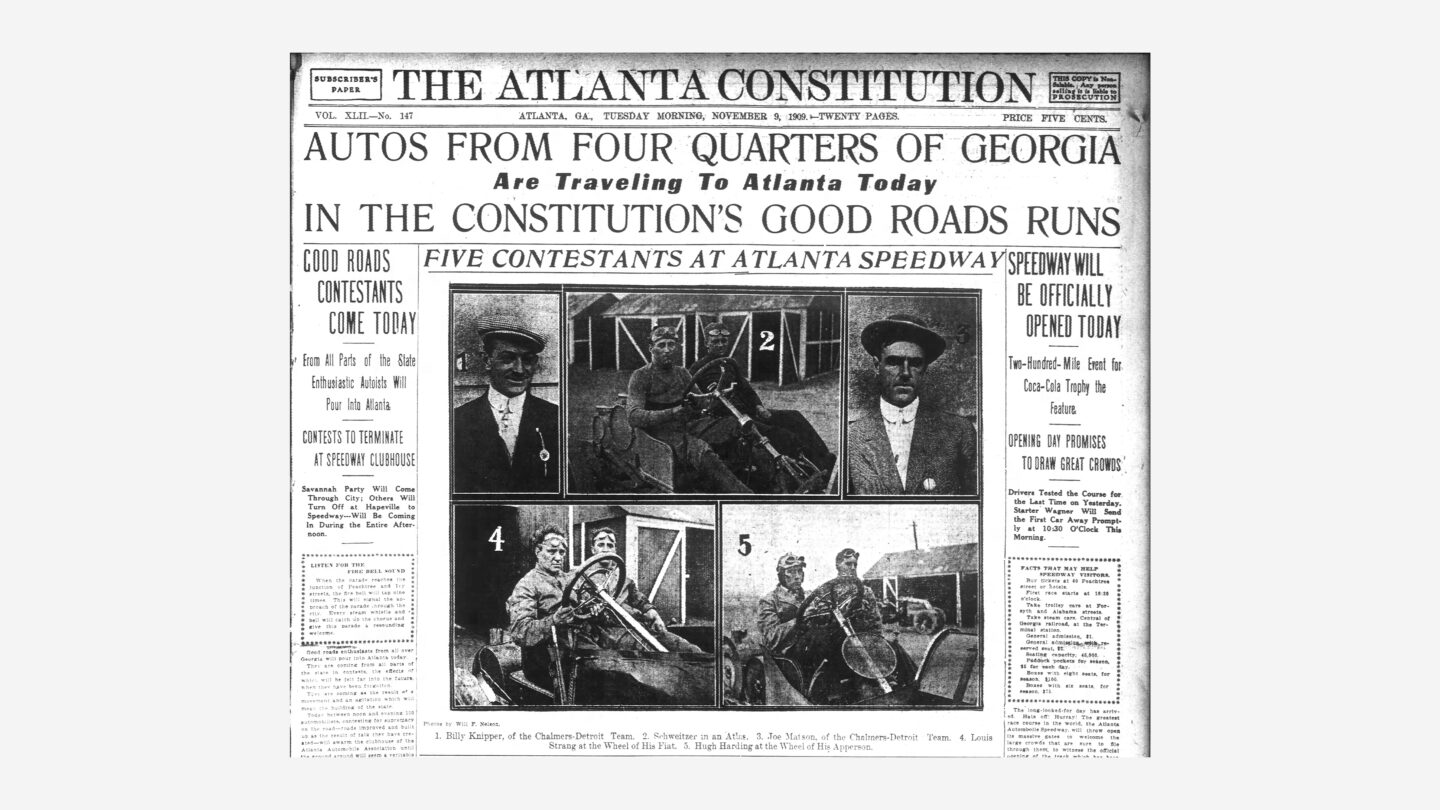

“Five Contestants At Atlanta Speedway,” Atlanta Constitution, November 9, 1909, via Newspapers.com

The Atlanta Automobile Association promoted the speedway as the “fastest automobile track in the world” and offered entertainment featuring the world’s quickest cars. Racers vied for the Coca-Cola Trophy in its inaugural race on November 9, 1909. While the speedway was briefly a popular entertainment hub, it didn’t meet Candler’s expectations. Though aviation was still emerging, he saw the venue’s potential for aerial shows.

Aviation had captivated the world, and its potential for transportation was evident. Over the next decade, spectators filled the stands of the Atlanta Speedway for flight displays and car races; some even paid to ride as plane passengers.

Many early airfields, including Atlanta, began as tourist and entertainment spots. However, World War I shifted perceptions as officials recognized the importance of aviation in military operations and airmail.

In 1925, Candler leased the Atlanta Speedway property to the city of Atlanta for five years, establishing it as an aero landing field. This move began Atlanta Speedway’s transformation into an operational airport.

Airplane at Candler Field, circa 1927. Atlanta History Center Postcard Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The former speedway was soon dubbed Candler Field, and the Candler family sold the property to the city in 1928. The location continued hosting aerial exhibitions through the 1930s, and Atlanta emerged as a key airmail hub.

William Berry Hartsfield, 1913. William Berry Hartsfield Papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University via New Georgia Encyclopedia

William Berry Hartsfield (1890–1971)

Perhaps no one was more excited about the Candler Field lease than Atlanta alderman, and later mayor, William Berry Hartsfield. An Atlanta native, Hartsfield began his career in law. His political journey started in 1922 with his election to the Atlanta City Council. Hartsfield always envisioned the city’s future and potential. From expanding Atlanta through annexation to prioritizing transportation, he consistently backed initiatives to position Atlanta nationally and internationally.

From the start of the Candler Field lease, Hartsfield was deeply involved in transforming the former speedway into a functional airport. In 1925, he chaired the city council’s Municipal Airplane Landing Field Committee. Hartsfield secured funds to establish Candler Field as an airmail route stop.

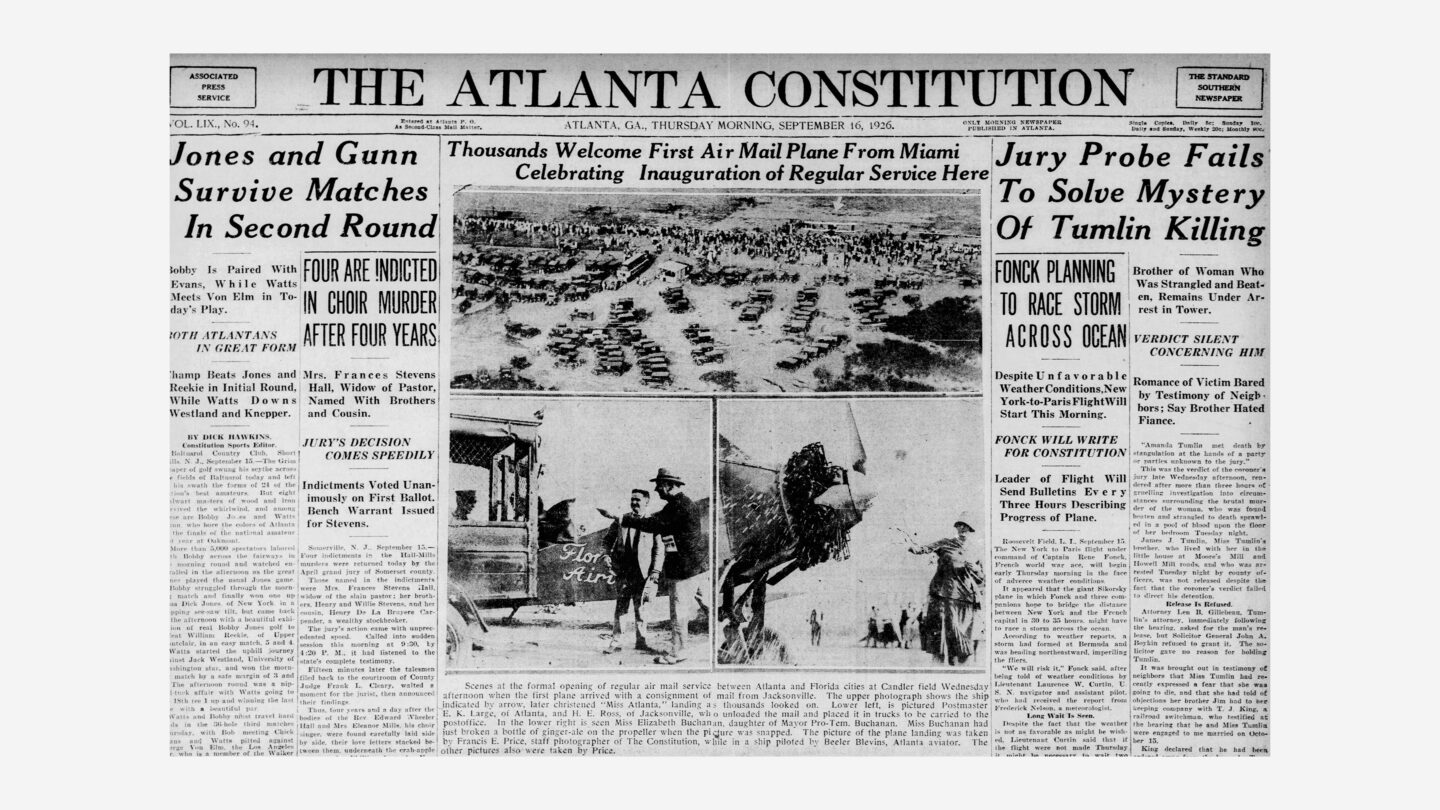

In 1926, the inaugural airmail plane from Miami touched down at Candler Field, signifying Atlanta’s commencement of regular airmail service. Hartsfield was instrumental in various other developments at Candler Field, such as turning it into a 24-hour operation with beacon lights for nighttime flights, securing Atlanta as the southern end for an airmail route from New York to the Southeast, and designating Atlanta as a drop point for a national east-west airmail path.

In 1928, the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce honored Hartsfield with a certificate, naming him Atlanta’s “father of aviation.” A year later, the city bought Candler Field from the Candler family for $94,000. The bond between Atlanta and the burgeoning aviation sector strengthened in the 1930s. In 1931, the city unveiled the U.S.’s first air passenger terminal, and by 1938, it erected the country’s inaugural air traffic control tower.

“Thousands Welcome First Air Mail Plane From Miami Celebrating Inauguration of Regular Service Here,” Atlanta Constitution, September 16, 1926, via Newspapers.com

When Hartsfield took office as Atlanta’s mayor in 1936, the city’s role as a critical air center was cemented. He was mayor for six terms, serving from 1937 to 1941 and again from 1942 to 1961, making him the longest-serving mayor in Atlanta’s history. Throughout his tenure, Hartsfield consistently backed the airport’s expansion. Under his leadership, the airport saw numerous milestones as it blossomed into a prominent commercial center. Candler Field grew substantially, establishing itself as a vital hub for Eastern Air Lines and connecting Atlanta to major U.S. cities. In 1941, Delta relocated its headquarters to Atlanta from Monroe, Louisiana. The airport also adopted a new name: Atlanta Municipal Airport.

In 1955, the Atlanta airport ranked as the eighth busiest in the U.S. By the next year, Atlanta Municipal Airport became the world’s busiest airport transit hub. Though Hartsfield left his mayoral post in 1961, investment in the airport persisted due to the foundation he laid. After his death in 1971, Atlanta Municipal Airport was renamed William B. Hartsfield Airport in tribute. With Eastern Air Lines’ inaugural international flight to Mexico from Atlanta in July of that year, the airport’s name was updated to William B. Hartsfield International Airport.

Eddie Rickenbacker photographed by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1926. University of Washington via Wikimedia Commons

Edward “Eddie” Rickenbacker (1890–1973)

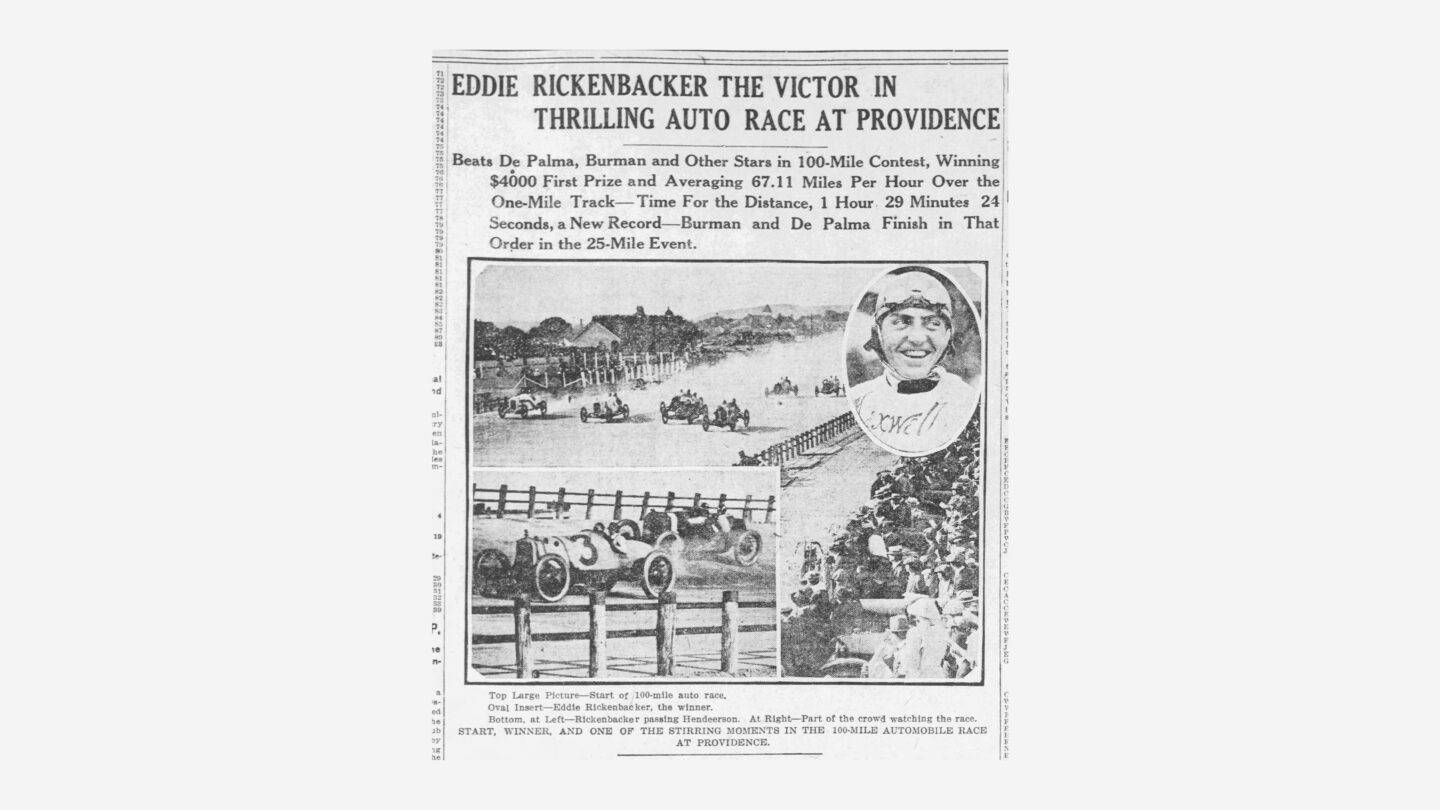

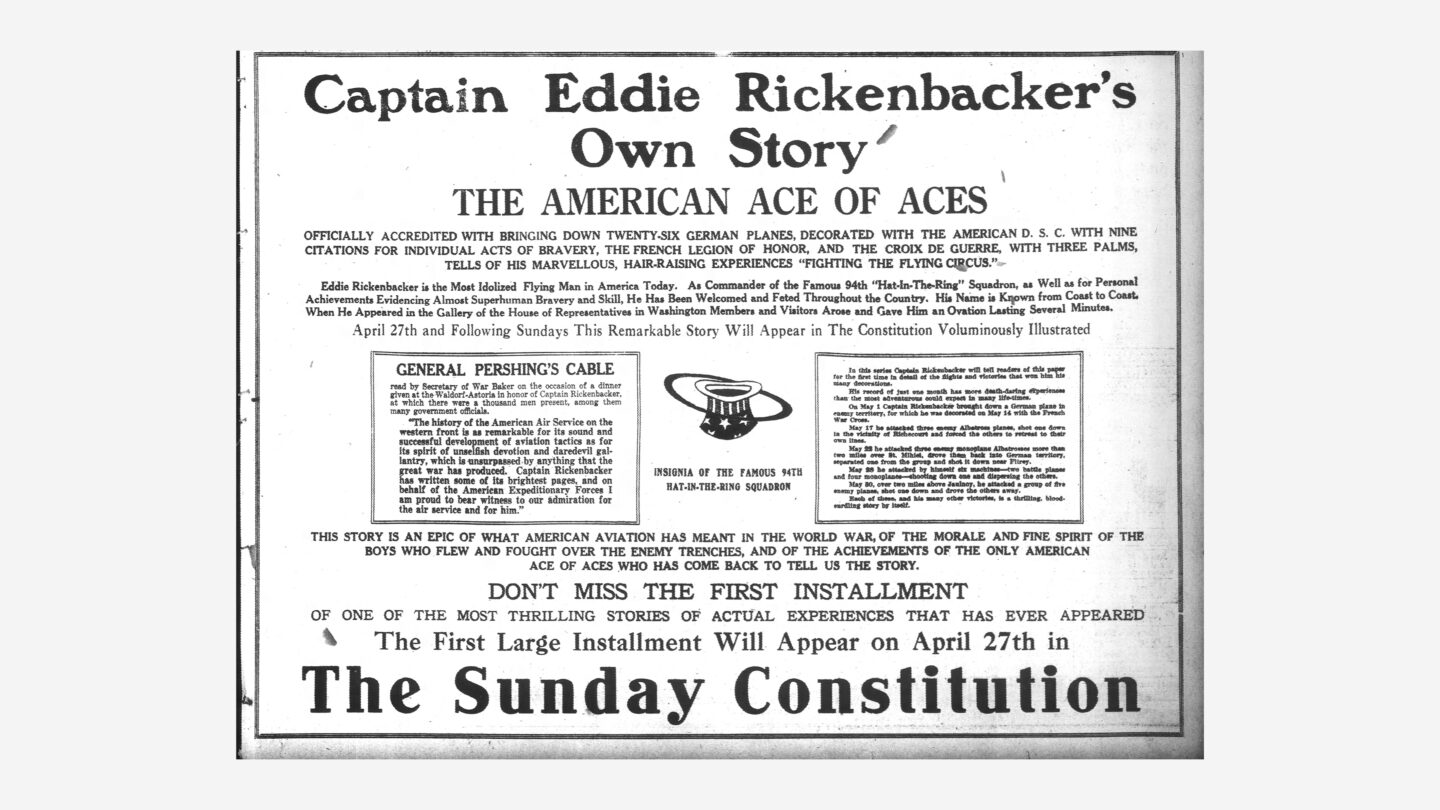

Eddie Rickenbacker, the son of Swiss immigrants, grew up in Columbus, Ohio. After his father Wilhelm died in 1904, Rickenbacker began working in the automobile industry. By age 20, he held the position of branch sales manager at Columbus Buggy Company. Rickenbacker took up auto racing to promote the Firestone-Columbus, a Columbus Buggy Company gas-powered automobile. Rickenbacker quickly became a racing star. By the close of the 1916 automobile racing season, he clinched four American Automobile Association races and finished third in the AAA Championship. In 1917, Rickenbacker paused his racing endeavors to join the military, serving as a combat pilot during World War I. Rickenbacker earned the moniker “Ace of Aces.” An “ace” is defined as a pilot with five aerial victories.

After a distinguished military stint, Rickenbacker pivoted back to automobiles, launching Rickenbacker Motor Company alongside partners Byron F. Everitt, Harry Cunningham, and Walter Flanders. After the company declared bankruptcy in 1927, Rickenbacker turned to aviation. He aligned with General Motors in 1928, advocating for the company’s acquisition of Fokker Aircraft Corporation. By 1935, GM elevated Rickenbacker to general manager of Eastern Air Lines, which GM owned. Under Rickenbacker’s guidance, Eastern Air Lines flourished. In 1938, Rickenbacker spent $3.5 million to acquire Eastern.

Eastern Air Lines plane parked in front of Atlanta Municipal Airport, 1936. Bill Wilson, Bill Wilson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Before World War II, many airlines relied on government subsidies for fiscal stability. Rickenbacker aimed to reshape Eastern into a self-sustaining enterprise. Gradually, he reduced the company’s dependence on subsidies, and post-World War II, Eastern emerged as a profitable airline. Candler Field played a pivotal role in Eastern Air Line’s story. The transformation of Candler Field into a full-service airport allowed Eastern to establish new passenger routes to and from Atlanta while maintaining airmail paths through the city.

Eastern Air Lines Hanger at Hartsfield Atlanta International Airport, 1990. Cotten Alston, Cotten Alston Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Eastern remained a dominant airline at Candler Field, later renamed Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, alongside Delta Air Lines. Eastern Air Lines was responsible for the elevation of the Atlanta airport to international status with the airline’s 1971 flight to Mexico. Eastern Air Lines also significantly boosted Atlanta’s economy, solidifying the city’s reputation as an important transportation and commercial hub in the South. Rickenbacker retired from Eastern Air Lines in 1963 and passed away in 1973. Eastern went out of business in 1991 due to mounting debts, a corporate takeover, and a resultant massive labor strike.

Maynard Jackson at a press conference in Atlanta, Georgia, circa 1975. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr. was the son of Maynard Jackson, Sr., and Irene Dobbs Jackson. As the grandson of Georgia Voters League founder John Wesley Dobbs, a history of civic and political engagement was in Jackson’s lineage. At 18, he graduated from Morehouse College and later earned his law degree from North Carolina Central University in 1964. He practiced law until 1968, when he ran for a seat in the U.S. Senate against incumbent Senator Herman Talmadge. Though Jackson did not win the 1968 senate race, his profile in Atlanta politics soared. In 1970, when Sam Massell became Atlanta’s mayor, Jackson was backed heavily by the city’s Black residents and selected as vice mayor. He made history as Atlanta’s first Black vice mayor. Jackson’s widespread support, especially from Black leaders, propelled him to victory in the 1973 Atlanta mayoral race. Jackson was mayor of Atlanta from 1974 to 1982 and again from 1990 to 1994.

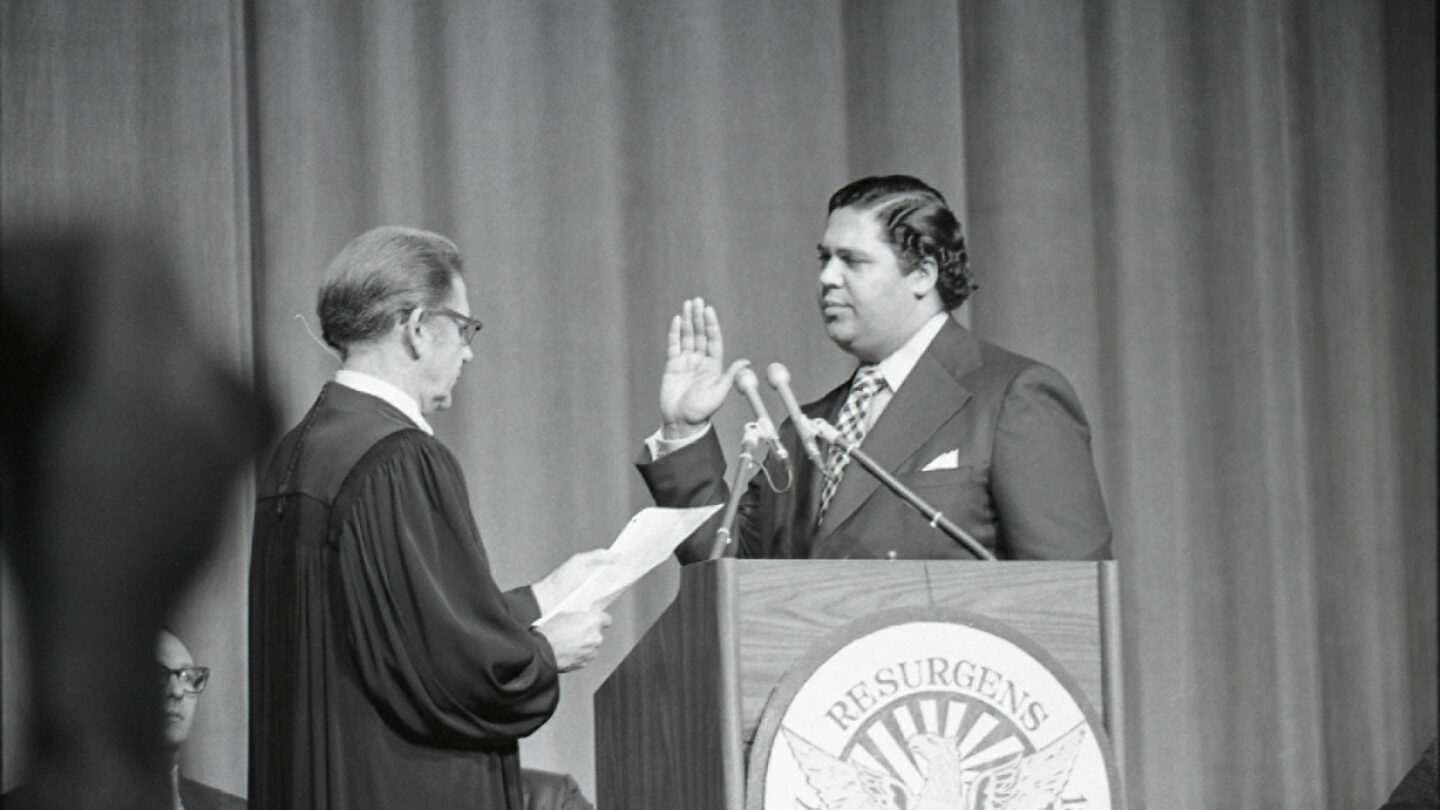

Honorable Luther Alverson swearing in Maynard Jackson as the Mayor of the city of Atlanta, 1974. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Jackson’s tenure as mayor transformed Atlanta and the South. At 35, he became the first Black mayor of Atlanta and of any major Southern city.

A standout initiative under Jackson was an affirmative action program that required 25% Black participation in city government contracts, including those awarded for airport construction. As Jackson pushed for airport growth, this program was especially influential. In 1973, minorities received less than 1% of all city contracts. By 1976, that number had risen to about 39%. Jackson’s approach had such a profound effect that the airport’s expansion finished both under budget and ahead of schedule. The success of his affirmative action program led the Federal Aviation Administration to recommend minority contractor involvement in airport projects nationwide.

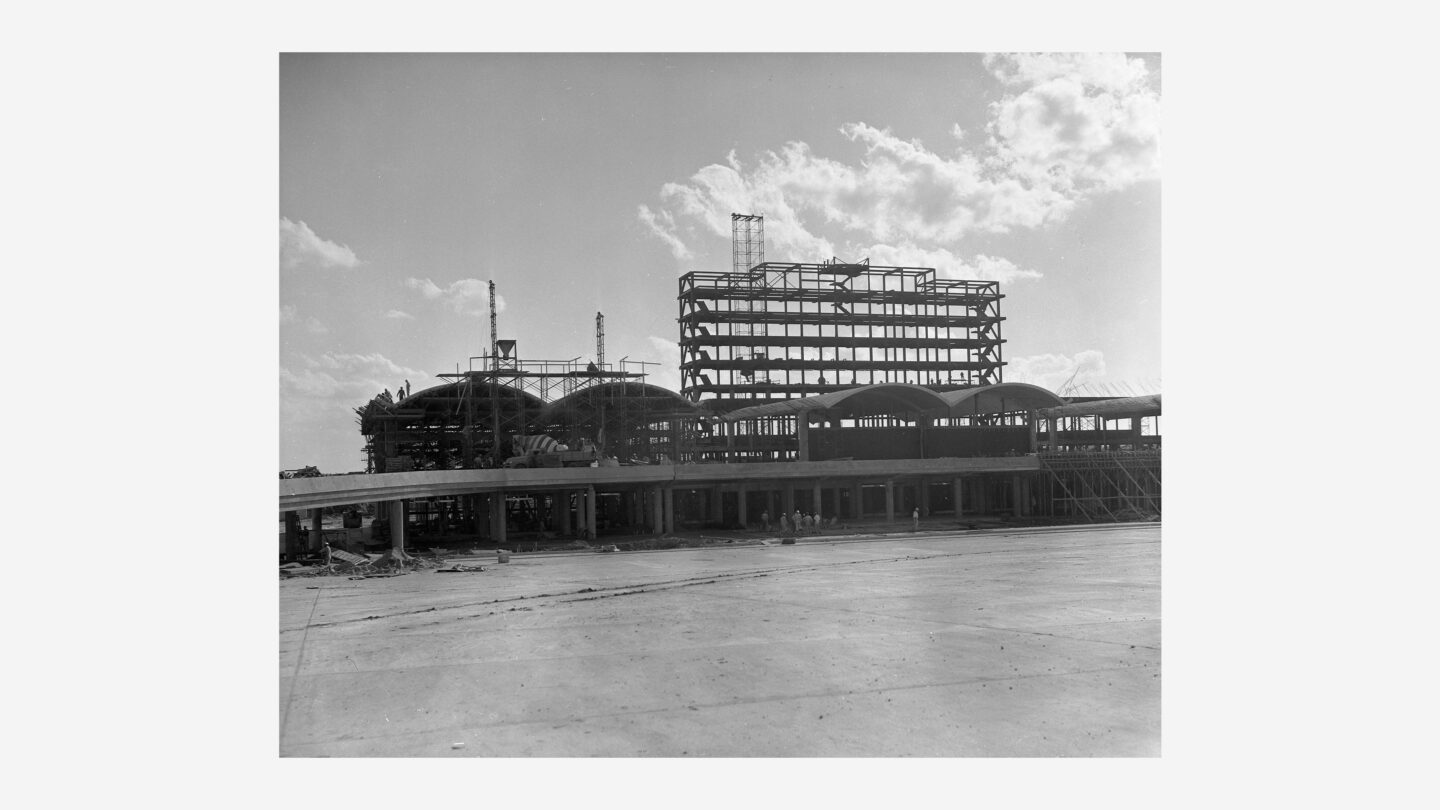

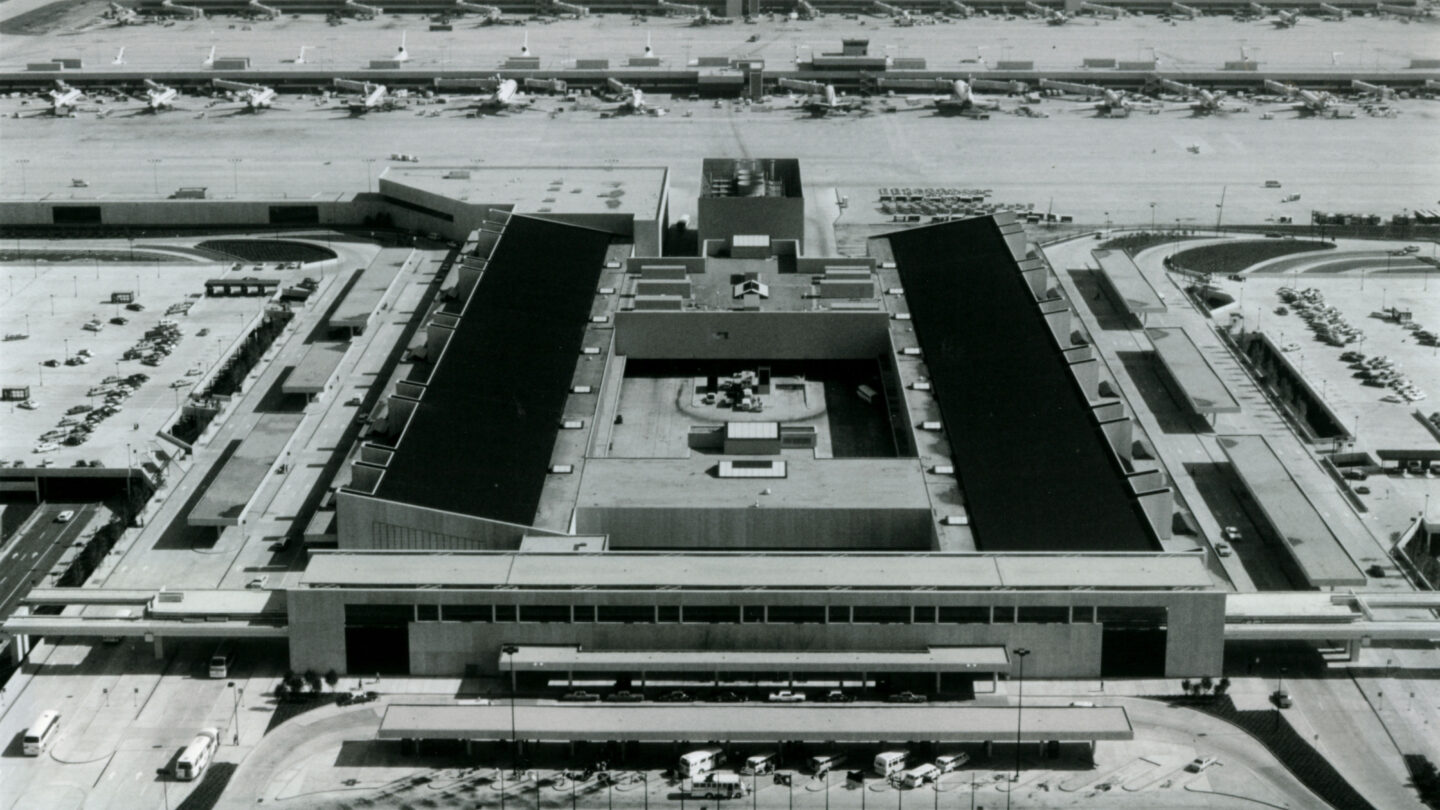

Under Jackson’s leadership, the William B. Hartsfield International Airport opened “Midfield” in 1980, an innovative passenger transfer hub allowing travelers to reach terminals via an underground transportation mall. Jackson viewed this advancement as establishing Atlanta as a model for the future.

“We stand not so much as a gateway to the South but as a gateway to a new time, a new era, a new beginning for the cities of our land,” Jackson said of the achievement.

During Jackson’s final term as mayor in the early 1990s, he strongly backed Atlanta’s bid to host the 1996 Olympics. Given an airport and a city equipped to accommodate global travelers and Olympic teams, Jackson’s efforts were instrumental in Atlanta securing the bid. Although political and business leaders such as Asa Candler, Eddie Rickenbacker, and William Hartsfield laid the foundation for the airport, Jackson propelled both the city and the airport into a modern era.

Jackson died in 2003 at age 65. The airport was renamed Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport in honor of his contributions.