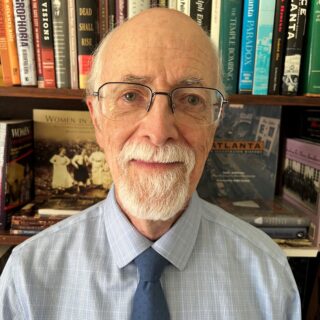

John Temple Graves was a prominent American newspaper editor, a New South orator, and the author of many essays, opinion pieces, and speeches in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that focused on segregation, race riots, lynchings, and the Southern race problem.

John Temple Graves. The American Review of Reviews, Volume 38

Born in Willington, South Carolina, in 1856, Graves was the great-grandnephew of John C. Calhoun, a United States senator and the U.S. vice president from 1825-1832. Like his ancestor, Graves was active in politics. He served as a presidential elector for Florida in 1884 and Georgia in 1888. And in 1908, Graves was selected as the vice-presidential candidate for the Independence Party.

Despite these political forays, Graves’s career and growing national reputation was primarily centered around his success as a journalist, orator, and newspaper editor. From 1882 to 1925, Graves was actively involved with newspapers in Florida, Georgia, Washington, D.C., and New York. In Georgia, he served as the editor-in-chief of the Tribune of Rome from 1887 to 1890 before moving to Atlanta, where he became editor of the Atlanta Journal and later the Atlanta Evening News. He later teamed up with Frederick Loring Seeley in 1906 to launch a new evening paper called the Atlanta Georgian. With an initial subscription of 17,000 readers, the Georgian quickly became Atlanta’s third-largest daily newspaper and a strong competitor to the Atlanta Constitution, the Atlanta Journal, and the News.

1906 photograph of Atlanta Georgian composing room. Georgia University Special Collections, Edmond Torbush Papers, Southern Labor Archives

The growing competition among Atlanta’s four white newspapers for subscribers led to a circulation war in the summer of 1906, during which all four papers ran lurid stories of Black male assaults on white women in Georgia that were exaggerated or fabricated.

The Atlanta Georgian, under Graves’s guidance, had advocated for prohibition, criticized Georgia’s convict-lease system, and supported child labor laws. Still, these issues took a back seat to the race-baiting articles and stories of Black assault and rape that were featured on the Georgian’s front page.

Collectively, these newspaper stories helped inflame racial tensions in the city and partly contributed to the outbreak of the Atlanta Race Massacre in September. Over a three-day period, mobs of white men attacked African American men, businesses, and homes and murdered dozens of people before order was restored, and an estimated 1,000 Black citizens and families left the city after its conclusion.

Front page of the Atlanta Georgian , September 24, 1906. Georgia Newspaper Project, Georgia Historic Newspapers

The Atlanta Georgian’s negative portrayal of African Americans and racial equality was not simply the result of an aggressive newspaper circulation battle in the city. It also reflected themes, issues, and solutions that Graves frequently referenced in his writings and speeches.

Throughout his newspaper career, Graves remained a staunch advocate of racial segregation and the superiority of the white race. And, as the numbers of lynchings and violent mob attacks on African Americans in the South continued to rise in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he often justified these extralegal actions as necessary restraints against Black criminals and rapists.

In a speech Graves gave in Chautauqua, New York, in 1893, he proclaimed, “This is a white man’s government, and it will remain so forever, for God Almighty has stamped his seal and sign of sovereignty upon the Anglo-Saxon tribe.” Six years later, Graves contributed an essay entitled “The Race and Social Problems” for an Atlanta Constitution piece that featured the views of newspapers, publicists, and readers regarding the torture and lynching of Sam Hose in Newnan, Georgia.

In his essay, Graves begins by affirming that “I deplore to the very core of my citizenship the barbarities which sheer rage and frenzy evoked from an outraged people at Newnan on the 23rd.”

But he then goes on to say that “The core of the question is, of course, the suppression of rape… The mob is practical about this matter. While sentimentalists are resolute on lynch law, the mob acts on rape. Let the sentimentalists learn a lesson here from the mob. Let them orate less on lynchings and act more earnestly and practically for the suppression of rape.”

Graves concludes his essay with the declaration that “These two opposite and inherently antagonistic races cannot grow up side by side on equal terms of law and possession in the same territory. . . Separation is the logical, the inevitable, the only solution of this great problem of the races.”

“This is a white man’s government, and it will remain so forever, for God Almighty has stamped his seal and sign of sovereignty upon the Anglo-Saxon tribe.”

In 1903, John Temple again vigorously defended lynching in another address to a Chautauqua audience.

“The problem of the hour is not how to prevent lynching in the South, but the larger question: How shall we destroy the crime [rape] which always has and always will provoke lynching? … As a sheer, cold patent fact, the mob stands today as the most potential bulwark between the women of the South and such a carnival of crime as would infuriate the world and precipitate the annihilation of the negro race. . . The negro is a thing of the senses, and with this race and with all similar races, the desire of the senses must be restrained by the terror of the senses.”

When the Atlanta Race Massacre broke out in September of 1906, the degree of violence, death, and destruction shocked many of the city’s white leaders. It also threatened Atlanta’s image as a progressive New South city. National and International publications from New York to Paris condemned the violence, with the French newspaper Le Petit Parisien calling it the “Massacre De Negres” and a headline in the San Francisco Chronicle warning that “All South Ready for War Upon Negro.”

The negative press attention also threatened the city’s financial status. As lawyer, Charles T. Hopkins noted, “Saturday evening at 8 o’clock, the credit of Atlanta was good for any number of millions of dollars in New or Boston or any financial center. Today we couldn’t borrow 50 cents.”

Cover of the French magazine, Le Petit Journal, October 7, 1906, depicting a drawing, titled “Massacre of Negroes at Atlanta.” Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

To address these issues, white and Black city leaders met to discuss ways to avert future racial conflicts and organized a collection to help bury the victims and support their families. An inquiry was also conducted by the Chamber of Commerce and a Fulton County grand jury to determine the causes of the event, and both concluded that primary responsibility lay with irresponsible newspaper reporting.

John Temple Graves, however, continued to offer a different explanation for the outbreak of racial violence in Atlanta. In response to inquiries from the Washington Post, the Chicago Examiner, and the New York World, Graves sent a letter (by telegram) to the World on September 23, 1906, that declared “The Atlanta race riot is due to the cumulative provocation of a series of assaults by negroes upon white women, which, in number, in atrocity, and unspeakable audacity, are without parallel in the history of crime among Southern negroes.”

After his letter was published by the New York World, Graves was denounced by the New York Post as “an apostle of lynching” and by The Broad-Ax (in Chicago) as “the wild-eyed Anarchist, and the bold and bloody advocate of mob and lynch law for Colored men.”

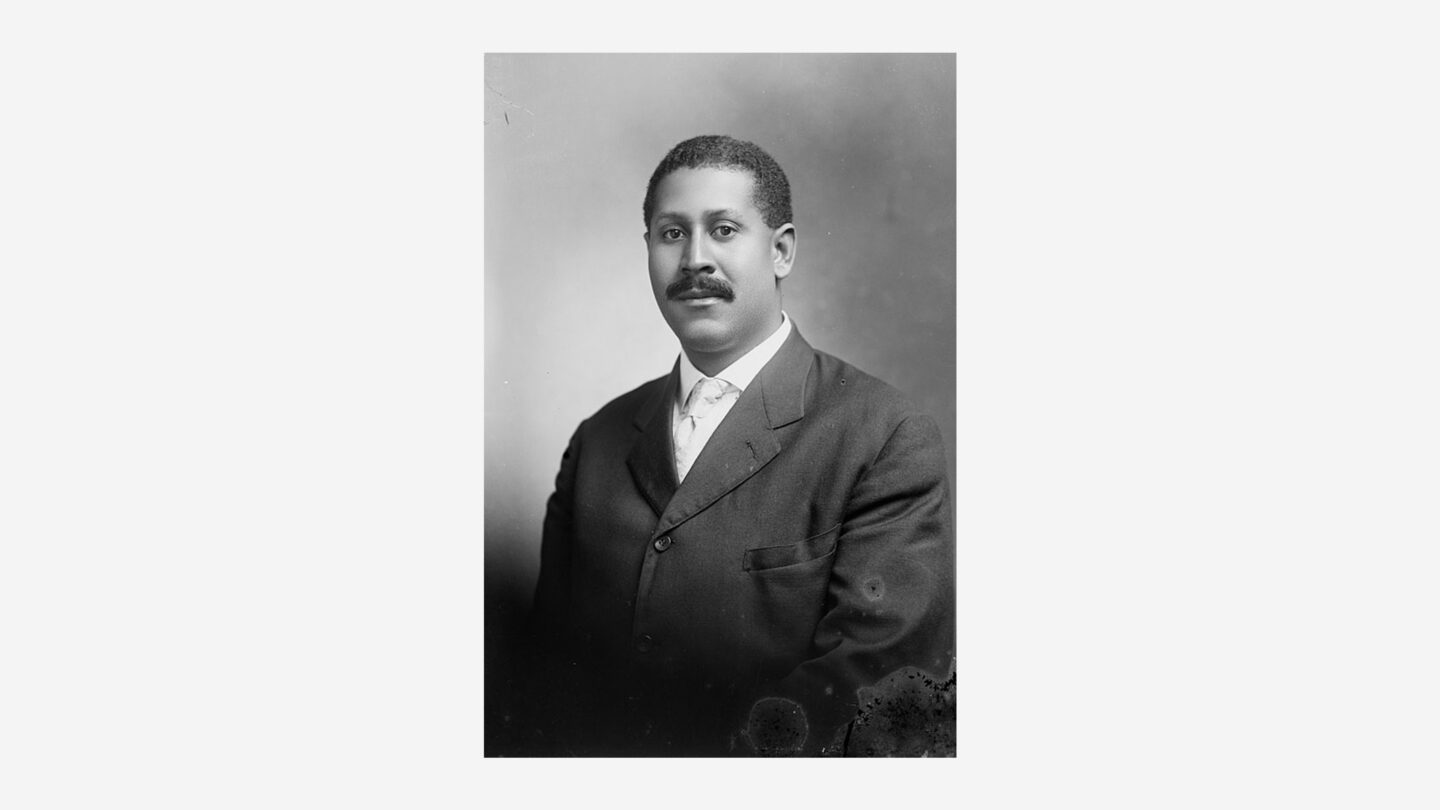

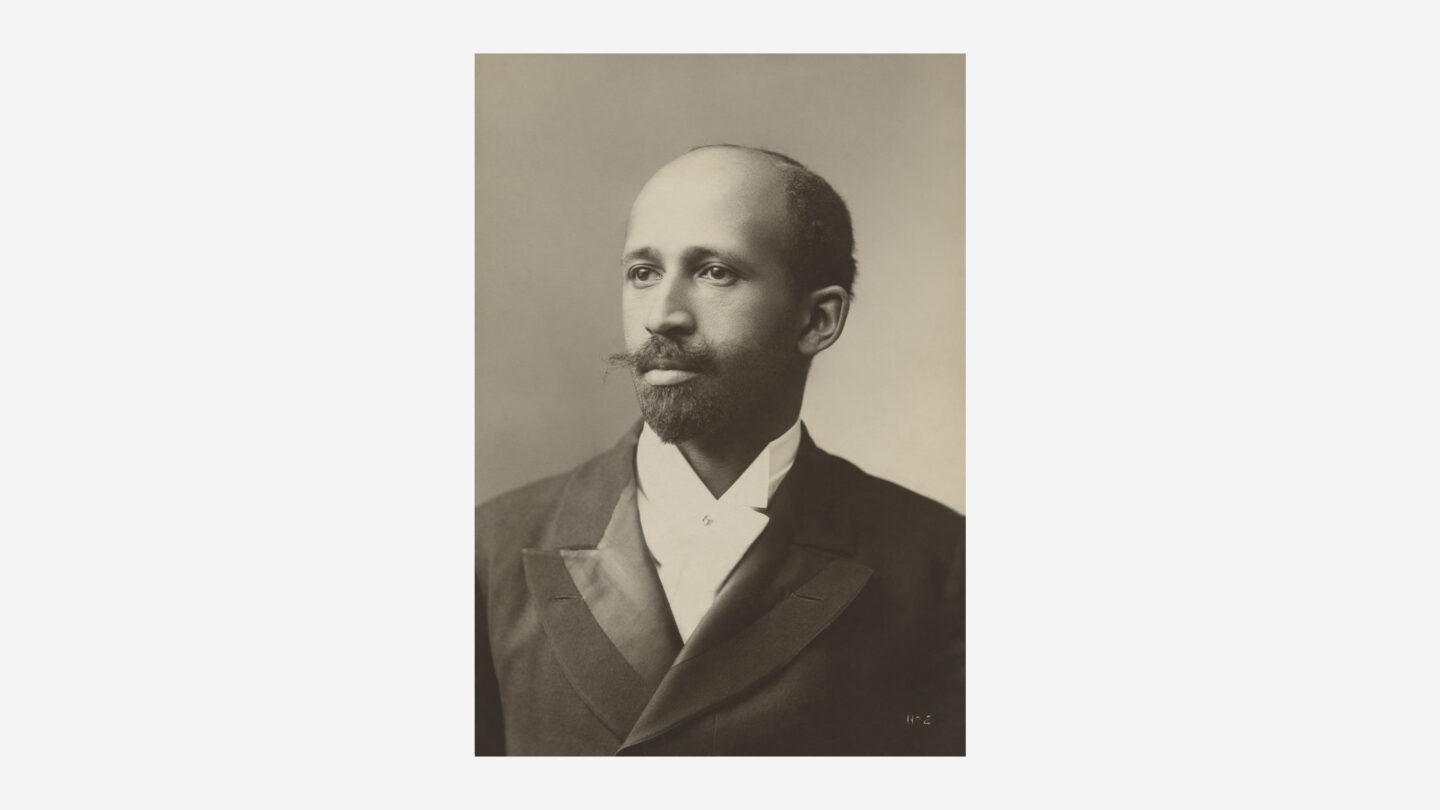

Back in Atlanta, Graves’ explanation for the cause of the massacre also met challenges by African American sociologist, historian, and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois, who taught at Atlanta University, and Jesse Max Barber, co-editor of the Voice of the Negro. In a 1906 article entitled “The Tragedy at Atlanta:

From the Point of View of the Negroes,” Du Bois rejected Graves’ account of the massacre. “The alleged cause of this riot was the raping of white women by Negroes culminating in four cases on the day of the riot. . . The real cause of the riot was two years of vituperation and traduction of the Negro race by the most prominent candidates for the governorship, together with a bad police system and a system of punishing crime which is a disgrace to any civilized state.”

Du Bois concluded his essay by urging that “The Negro must have the ballot. Only in this way can he peacefully defend his life and property . . .”10 [“The Tragedy of Atlanta, November 1906

After Barber read Graves’s letter to the World, he called the newspaper and requested the opportunity to write a rebuttal. The newspaper agreed and promised to publish it as an anonymous letter from a “Colored Citizen.”

In his rebuttal, Barber wrote, “John Temple Graves assumes a grand air of fairness in his letter of two days ago to the New York World. But in all that pageantry of high-sounding phrases, he seeks an excuse for a mob which was as lawless and godless as any savages ever shocked civilization. . . The cause of this riot: Sensational newspapers and unscrupulous politicians.”

Barber’s letter also pointed blame at white elites and suggested that some of the alleged acts of violence had been staged by supporters of Hoke Smith (a candidate for governor in 1906), who were wearing Blackface to pose as African Americans. The anonymous letter caused quite a stir in Atlanta, and one day after he wrote it, Barber got a call from Captain James English ordering him to meet him at his offices.

English had recently been appointed head of the “Committee of Ten” (comprised of white civic and business leaders) and had been given the power to oversee law enforcement in Atlanta.

When Barber met with English, he was informed that the anonymous telegram he sent to the New York World had been traced to his office and that he could either go to the Grand Jury and prove his innocence, leave town, or be sentenced to serve on a chain gain. Barber decided to leave town and continued publishing the Voice in Chicago.

In February of 1907, the Georgian purchased the Atlanta News (which was bankrupt) and was renamed the Atlanta Georgian News. Later that same year, Graves left Atlanta to become editor of William Randolph Heart’s New York American but continued his connections to the city and the Georgian as a special contributor.

And it was in this capacity as a special contributor that John Temple Graves in 1914 first floated the idea in a guest editorial of carving a likeness of Robert E. Lee into the side of Stone Mountain as a memorial to the Confederacy.

In the June 14, 1914 edition of the Atlanta Georgian and News, he wrote, “To the veterans of the dead Confederacy, to the daughters and sons, and to all who revere the memories of that heroic and immortal struggle, I bring today the suggestion of a memorial, perfectly simple, perfectly feasible, and which if realized will give to the Confederate soldier and his memories the most majestic monument, set in the most magnificent frame in all the world.”

The Atlanta Georgian and News was purchased by Hearst in 1912 and continued publication until 1939. John Temple Graves died on August 25, 1925, in Washington, D.C.