View of the silverback gorilla known as “Willie B.” at the Municipal Zoo (now Zoo Atlanta) in the Grant Park area of Atlanta. (VIS 71.75.05, Floyd Jillson, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

When Willie B. died of heart failure in 2000 at the age of 42, a piece of Atlanta died.

The 400-pound, 6-foot-tall silverback gorilla lived through many pivotal events in Atlanta’s history—from the Civil Rights Movement and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral to the establishment of the Atlanta Pride Festival, the Atlanta Child Murders, Freaknik, and the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games.

And like a faithful friend, Willie B. was a symbol of consistency and a source of comfort, who saw the city through the highs, lows, and growing pains it had to endure to become the international city it is today.

Yes, Willie B. was a gorilla at Zoo Atlanta, but he was much more to those who grew up in Atlanta. He was an Atlanta legend.

Willie B. got his name from Atlanta Mayor William Berry Hartsfield. He was born in 1958 in Africa’s western lowlands. In 1960, he was captured by an animal dealer in Kansas City and brought to Grant Park Zoo in 1961 to replace another gorilla named Willie B. at the urging of Mayor Hartsfield.

Willie B. became a popular attraction at the zoo and a favorite of Mayor Hartsfield, who even nominated the gorilla for Congress.

Children with campaign signs for the Zoo Atlanta gorilla “Willie B.” (LBME3-044b, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.)

Despite his popularity, Willie B. lived a depressing, solitary life in a tiled cage at the zoo. For nearly 30 years, his only companions were a television, which was famously stolen just before the 1979 NFL playoffs, a tire swing, and a caretaker. He never interacted with other gorillas or set foot outside his cage.

Gorilla Willie B. at Zoo Atlanta, Atlanta, Georgia, November 28, 1978. (AJCN022-075a, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.)

In 1984, after the highly publicized deaths of several exotic animals, Grant Park Zoo lost its accreditation and went into crisis mode after Parade Magazine named it one of the worst zoos in the country. The public shaming led many Atlantans to call for reforms at the zoo or for it to shut down. In response, Mayor Andrew Young assembled a task force to set the zoo on the right track.

The old zoo director, Steve Dobbs, was ousted, and Young tapped conservational biologist Terry Maple, then a professor at Georgia Institute of Technology, to turn things around.

“The zoo was depressing and an embarrassment to the city,” Maple said. “No one with any sense would have taken the job as director, but I did. I felt it was my duty after then-Mayor Andrew Young asked me to take the job.”

In 1985, Grant Park Zoo officially became Zoo Atlanta, a private, non-profit entity under the auspices of the Atlanta-Fulton County Zoo, Inc. With funds from the city, community, and corporate donors, Maple was able to revamp the zoo.

Zoo Atlanta redesign concept plan c. 1985 (Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

One of the chief features of the renovated zoo was the Ford African Rain Forest, a gorilla habitat that more closely mimicked natural jungle conditions. This habitat would become Willie B.’s new home.

On May 13, 1988, about 25,000 people came out to see Willie B. take his first steps outside in nearly three decades.

At first, Maple and the zoo staff were not sure how Willie B. would acclimatize to life outside around other gorillas.

“I had hope for him,” Maple said. “I was afraid the girls would beat him up, but they liked him a lot.”

Willie B. with his first mate Kinyani at Zoo Atlanta. (AJCN004-082a, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.)

Willie B. spent the rest of his days in the Ford African Rain Forest, eventually settling down with a female gorilla named Choomba. Choomba would go on to bear Willie B.’s five offspring, Kudzoo, Olympia, Sukari, Lulu, and Kidogo (also known as Willie B. Jr.).

In January 2000, Willie B. caught the flu, then pneumonia. Those maladies caused stress on his heart and led to his death. When he died, “He was surrounded by his gorilla family and the zookeepers who were caring for him,” Gail Eaton, a Zoo Atlanta spokesperson, said.

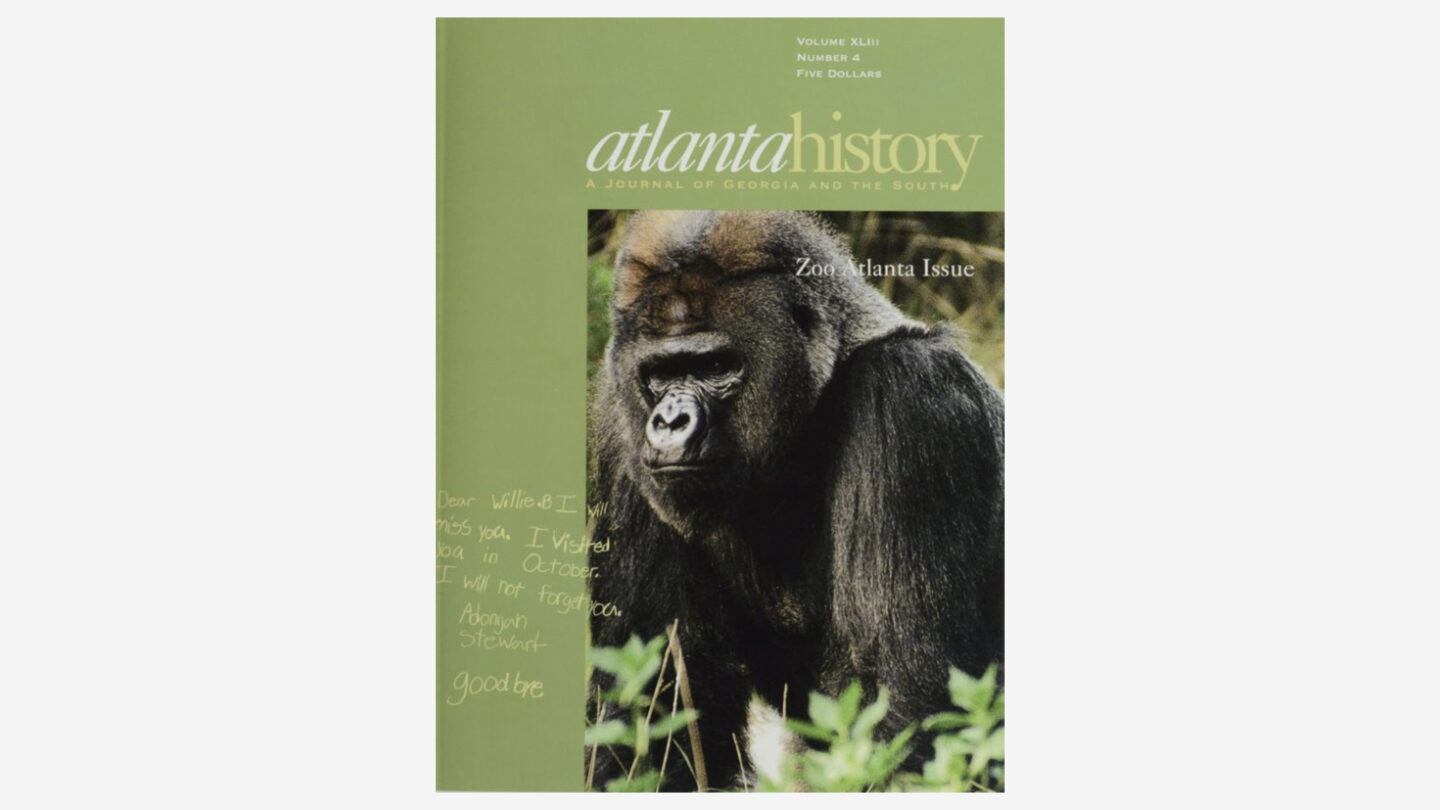

Cover of the Winter 2000 edition of Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South with a message to Willie B. (Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

More than 5,000 people attended Willie B.’s memorial ceremony. He was cremated. Eighty percent of his remains are inside a life-size bronze statue bearing his image outside the gorilla habitat. The other 20% of his remains were dispersed in the jungle in Africa, where he was born.

Maple said Willie B’s death was like “losing one of your closest friends. This was a magnificent animal, a great ambassador for the city, a great father. This will always be his zoo. He built it.”