An Air Atlanta Boeing 727 at Miami International Airport in Miami, Florida. Perry Hoppe, Wikimedia Commons

Quality product, quality service, and consistency often define a successful company. Air Atlanta exemplified all these attributes and more. This is its story.

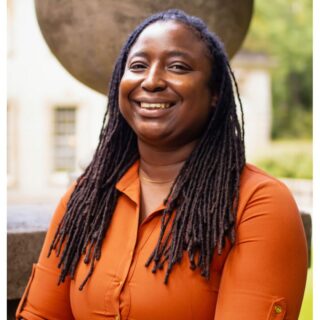

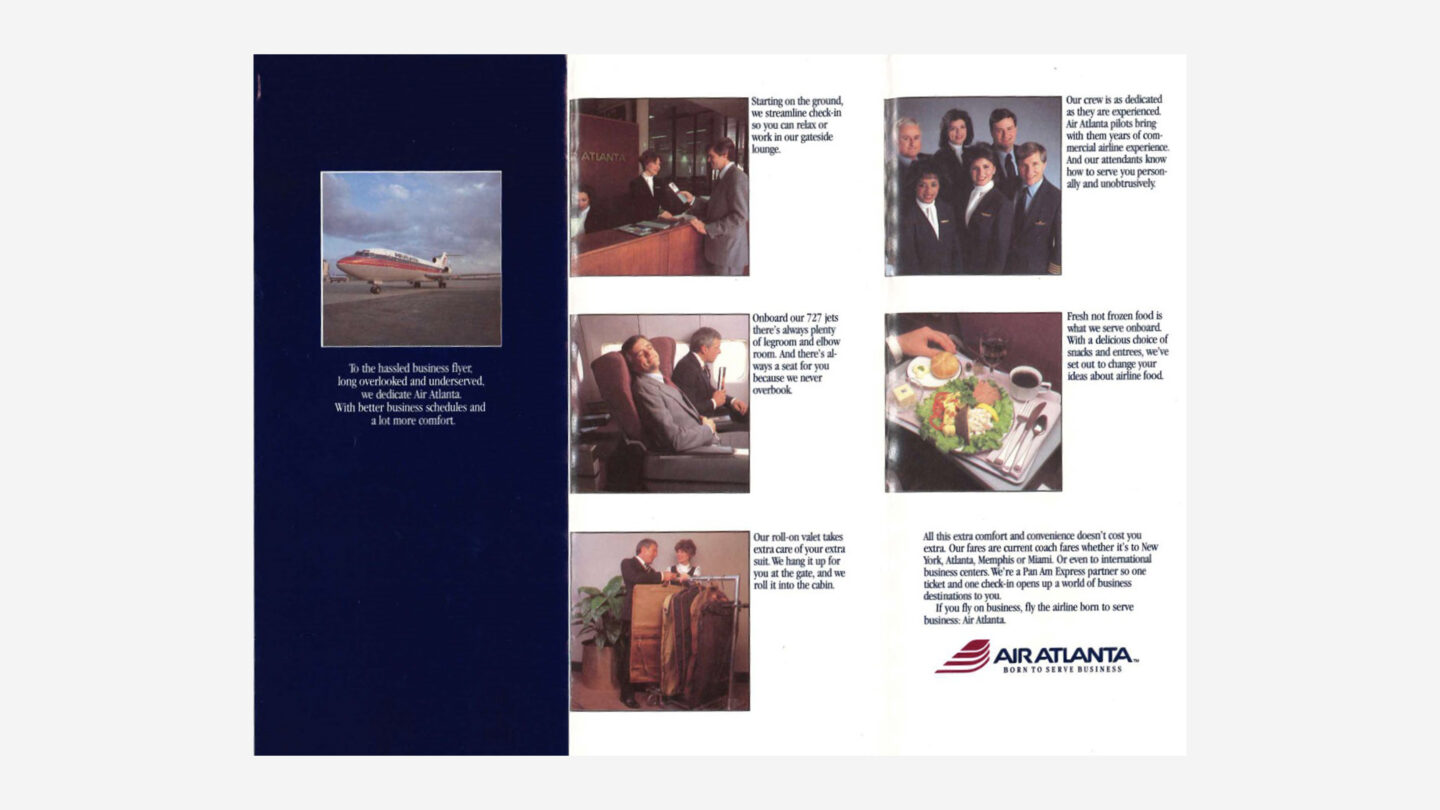

Air Atlanta was an anomaly in the airline industry. It was a low-cost carrier that ferried passengers in its distinctive gray, blue, and burgundy Boeing 727s to major destinations such as Miami, Tampa, Orlando, and Washington D.C. on time and in style. Air Atlanta’s jets sported roomy seats, plenty of legroom, fresh food on fine china, prize-winning wines, and gourmet meals. It was also a national Black-owned airline at a time when there were less than 320,000 Black-owned businesses in the country.

Air Atlanta wasn’t the first Black-owned airline. Warren Wheeler, a Piedmont Airlines pilot from North Carolina, started his own commuter airline, Wheeler Airlines, serving North Carolina and Virginia in 1969. Even though it wasn’t the first Black-owned airline, the scale and ambition of Air Atlanta were unmatched.

Michael Hollis on the cover of “Atlanta Weekly,” July 14, 1985. Air Atlanta Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Thinking Skyward

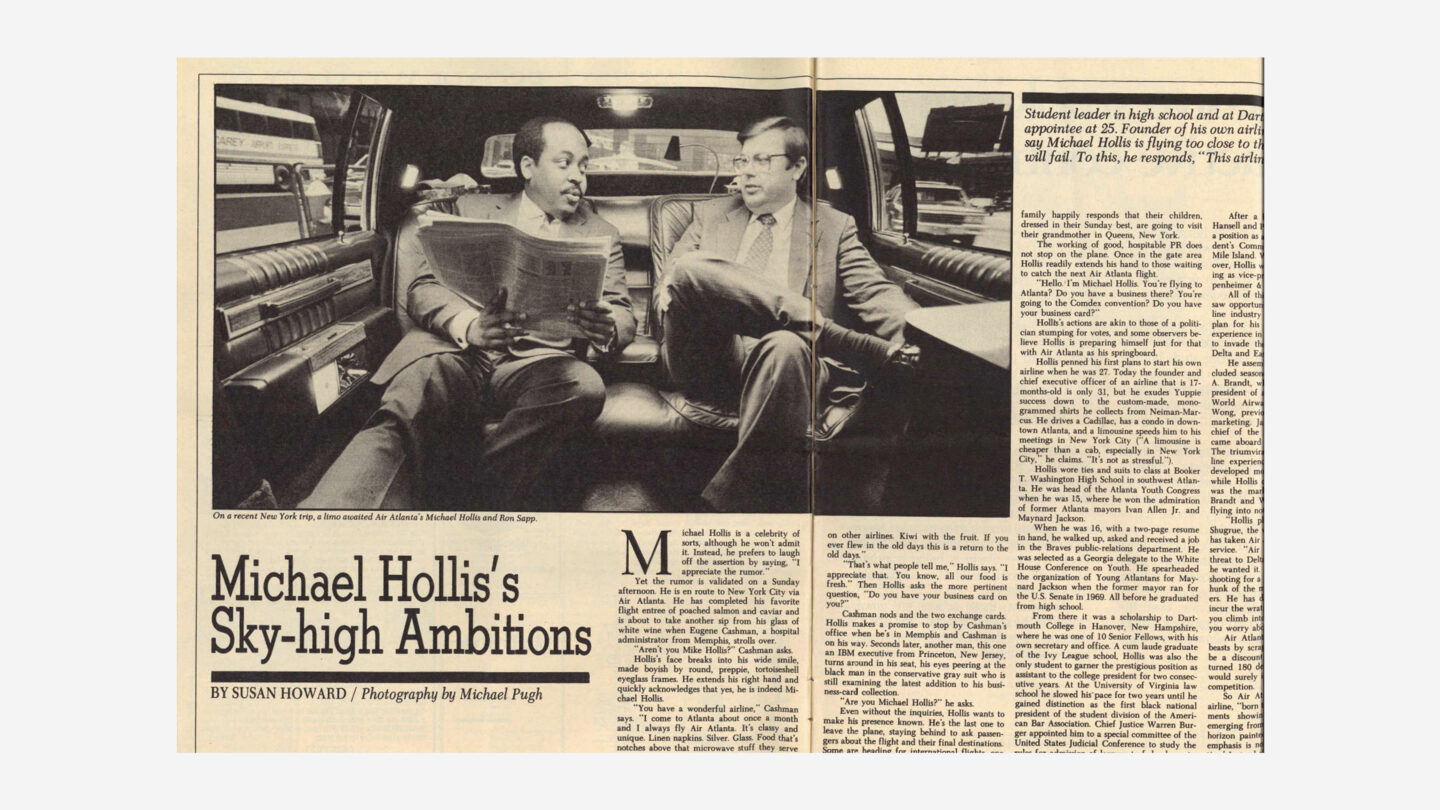

Lawyer and entrepreneur Michael Hollis was the Atlanta-born and raised visionary behind Air Atlanta. He was inspired to start the airline during a unique period in U.S. aviation history: Airline deregulation.

The Deregulation Act of 1978, championed by Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy and signed into law by Jimmy Carter, transformed the airline industry. It removed federal control over airline fares, routes, and the market entry of new airlines in the name of consumer rights.

The act aimed to introduce the free market in the commercial airline industry and increase the number of flights, passengers, and miles flown while decreasing airfares. Before airline deregulation, the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board tightly controlled airline operations, limiting growth and competition.

U.S. Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy signs an autograph for Mrs. Jo Ann Player at the Atlanta airport during a campaign visit in 1964. Kennedy would later go on to sponsor airline deregulation in 1978. Bill Wilson, Bill Wilson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Deregulation sparked a flurry of airline startups and gave Michael an idea.

Julius Hollis remembered a conversation with his brother Michael in the book, “In the Arena: The High-Flying Life of Air Atlanta Founder Michael Hollis,” where Michael shared his ambitious plan with him.

“I’m sitting in my office at the Export-Import Bank. Michael comes into my office, closes the door, and says, ‘Look man, I’m going to run something past you,'” Julius recalls. He said, “‘I’ve done my research, and with the deregulation of the airlines and the CAB, I’m going to put an airline together.'”

If he said he would start an airline, then you could bet he would start an airline.

Michael told his brother he was going to resign from his job at the New York investment firm Oppenheimer & Co. and put all his energy into starting an airline.

Although Michael had a good job at the time, according to attorney Daniel Kolber, a close friend and business partner of Michael’s, he had less than $500 in the bank and no airline industry experience.

Still, Kolber believed in Michael’s wild idea.

“But by that time, I knew Hollis well and what he was capable of,” Kolber said. “If he said he would start an airline, then you could bet he would start an airline.”

After sharing his vision with family members, Michael’s mother and godmother gave him their $35,000 life savings to jump-start his airline dream.

“That was the heaven-blessed seed money that he used to attract the first serious investment,” Julius said. “So, we couldn’t fail because that would be risking the life savings.”

In total, the Hollis family invested $100,000 into Air Atlanta.

After raising funds from family, Michael was able to attract investment from larger organizations such as the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees (NAPFE), a union founded in 1913 that initially represented African-American workers for the railway mail service. NAPFE invested $500,000 in the startup for 400,000 shares of stock.

A feature story on Michael Hollis in “Atlanta Weekly,” July 14, 1985. Air Atlanta Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Despite Michael’s limited experience in the airline industry and resources, his determination was unwavering. Air Atlanta was officially incorporated in Delaware in May 1981, with Michael leading as chairman and chief executive officer.

With the objective of building a trusted and credible airline, Air Atlanta welcomed experienced industry professionals into its fold. Notably, Roden Brandt from Pan American World Airways (Pan AM) joined as CEO in November 1981, Robin H.H. Wilson of Long-Island Railroad and Trans World Airlines (TWA), and James Purcell, a former official with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). These additions to the Air Atlanta family boosted the airline’s reputation, paving the way for major investments and CAB route approvals.

A news clipping mentioning Air Atlanta’s first flight in the Atlanta Constitution, January 30, 1984, Page 33, Newspapers.com

Taking Flight

Air Atlanta’s inaugural flight took off on February 1, 1984. The airline quickly garnered positive attention, with President Ronald Reagan praising it as a beacon of free enterprise.

It also earned enemies.

On the surface, both Delta and Eastern Air Lines tried to maintain an image of neutrality, avoiding direct opposition to Air Atlanta. However, their refusal to integrate interline features—which would combine schedules, ticketing, and baggage systems for a streamlined customer experience—suggested otherwise.

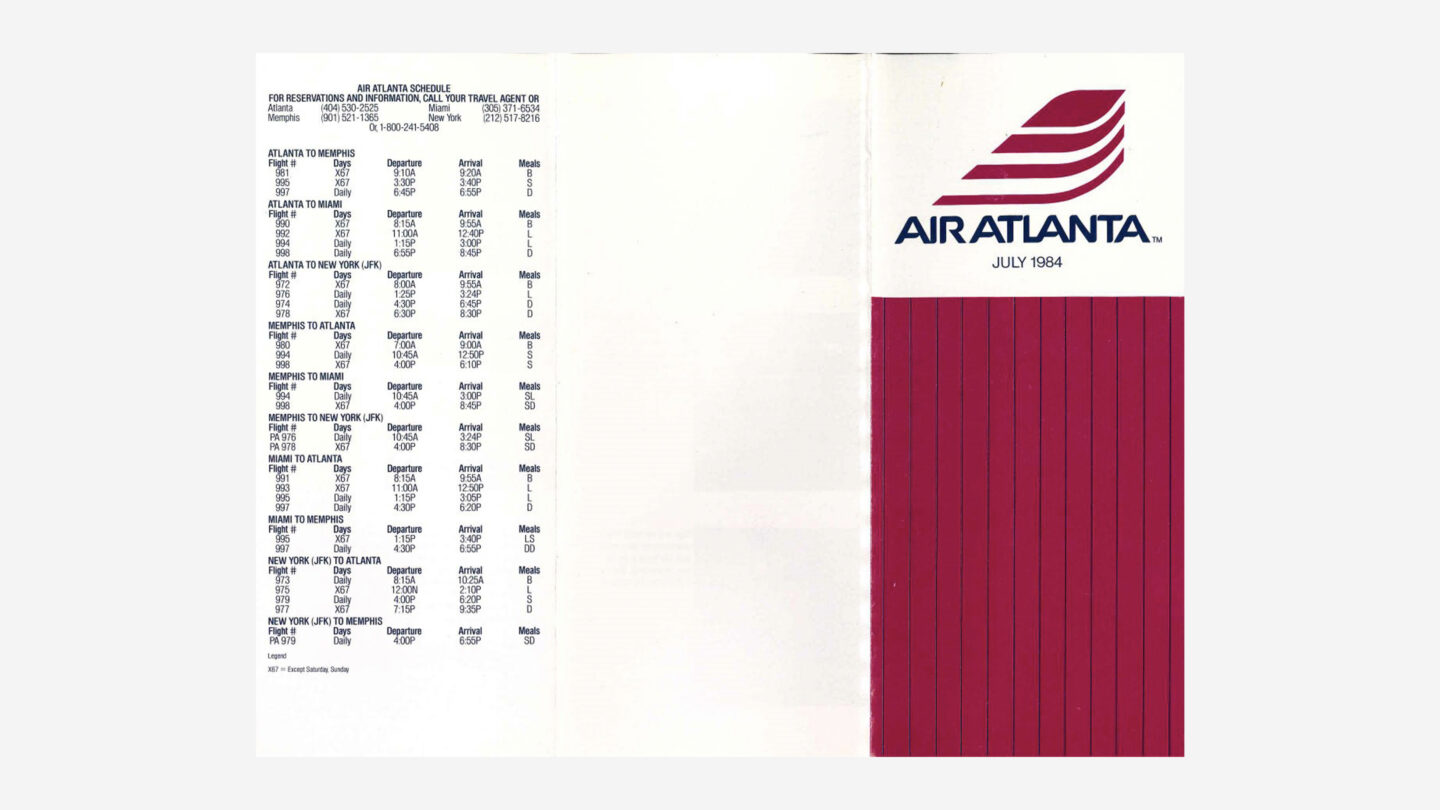

Air Atlanta timetable. Air Atlanta Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Delta, in particular, viewed Air Atlanta as encroaching on its territory. According to “In the Arena,” Delta, often referring to itself as Atlanta’s “hometown airline,” was unhappy with Michael’s decision to name his airline after Atlanta, a territory Delta considered uniquely theirs. Delta’s discontent was further exacerbated by the fact that Mayor Maynard Jackson, one of Michael’s childhood friends, endorsed Air Atlanta.

Delta’s influence extended to crippling Air Atlanta’s local fundraising efforts; notably, none of the major businesses in Atlanta showed a willingness to support the emerging airline financially. Mayor Jackson pointedly commented on this disparity in the Atlanta business landscape, suggesting that while the city’s white business elites might publicly celebrate diversity, their actions often revealed a contrasting narrative.

Losing Altitude

Despite a promising few years, 1987 proved to be a challenging year for Michael and Air Atlanta.

The tragic crash of a Midwest Air DC-9, similar in size to Air Atlanta’s 727s, was a stark reminder of the risks associated with aviation. Although Air Atlanta was not directly involved, such incidents often have ripple effects on the public’s perception of smaller carriers.

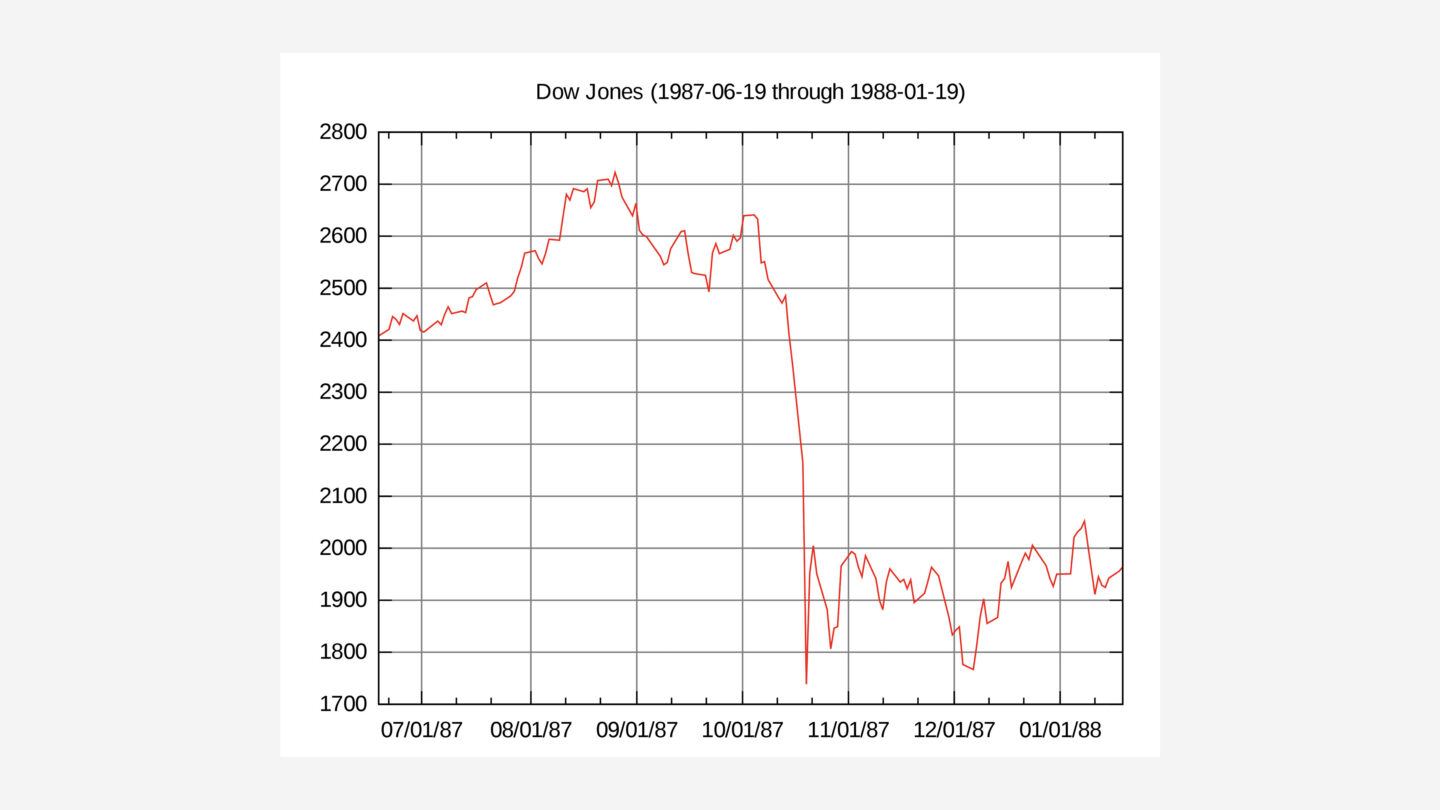

An image illustrating the 1987 stock market crash. Wikimedia Commons

Further complicating matters, the stock market crash of 1987, often referred to as Black Monday, created a volatile economic environment. It affected businesses across various sectors, and the airline industry, already grappling with thin margins, felt the strain.

Financial troubles for Air Atlanta came to a head when, despite having raised $80 million throughout its operation, Air Atlanta couldn’t secure an additional $10 million necessary for its survival. One of Air Atlanta’s early investors, Equitable, stipulated that Hollis and his board would need to resign in exchange for critical funding—a demoralizing proposition.

To add insult to injury, baseless rumors began circulating that Air Atlanta was involved in drug smuggling. These claims, though unfounded, tarnished the airline’s reputation at a time when public trust was paramount. In contrast, established airlines like Pan Am, Delta, and Eastern had employees convicted of smuggling operations worth billions, emphasizing the double standards new entrants such as Air Atlanta faced.

Amidst these challenges, personal tragedies beset Hollis. The murder of his socialite girlfriend, Lita McClinton Sullivan, by her estranged husband, was a painful blow. While not directly related to the airline’s operations, such personal traumas can affect decision-making and leadership at the helm of a company.

“Air Atlanta is Scratching Just to Pay the Rent,” Business Week, November 18, 1985. Air Atlanta Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Facing this insurmountable pile of challenges—from financial difficulties to a tarnished reputation—and lacking the support needed to weather the storm, Air Atlanta was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1987.

The dream that Hollis had nurtured, which had once soared high, was grounded.

New Horizons

Despite Air Atlanta’s demise, Michael’s spirit of entrepreneurship did not wane. He ventured into new businesses from radio stations (Hollis Communications along with Atlanta builder H.J. Russell) to petroleum retail (Blue Sky Petroleum Co.) and even a partnership with JP Morgan Chase (Nevis Securities). Michael also played a pivotal role in the Atlanta community, sitting on the boards of esteemed institutions such as Emory University and Atlanta University.

In 2012, Michael Hollis died at 58, leaving behind a legacy of ambition, determination, and innovation. The Michael R. Hollis Innovation Academy, a K-8 school in the Vine City/ English Avenue community, opened in August 2016 and was established in Michael’s honor.

The story of Air Atlanta is a testament to the tenacity of the human spirit. As Vice President of Properties at Atlanta History Center Jackson McQuigg pointed out, Air Atlanta faced impossible odds in the deregulated era. Its existence and brief success in such a competitive space is remarkable.

“My soapbox: Air Atlanta was amazing and had an amazing product. It also, in retrospect, never had a chance,” said McQuigg.

“Deregulation created openings for startups like Air Atlanta but also created the impossible odds of successfully building up a new airline to last,” he said.

“Scores of airlines have started up and failed in the wake of airline deregulation in 1978. It’s a very tough business, especially since deregulation allowed so many of the carriers to merge. Today there are only five major domestic airlines in the United States (eight if you count Spirit, Frontier, and JetBlue—which are somewhat smaller)—deregulation brought us that, too.”