Since the early days of flight, women have made their mark in aviation, a domain primarily dominated by men. Katherine Wright, who worked with her brothers, Orville and Wilbur, to create the first motor-powered aircraft, was among the early pioneers of flight.

The international journey of female aviators began when Raymonde de Laroche of France flew solo in 1909, becoming the first woman to earn a pilot’s license. Shortly thereafter, Harriet Quimby became the first American woman to acquire a pilot’s license in 1911 and fly across the English Channel in 1912. Female aviation firsts continued in 1921 when Bessie Coleman broke racial and gender barriers as the first Black and Native American woman to earn a pilot’s license.

Though there were many female aviation pioneers, the journey to the cockpit was perilous. Early flight took the lives of both Laroche and Coleman in plane crashes. Despite the inherent risks of early flight, women worldwide, including those from Georgia, took to the skies. Due to the era’s societal norms, they encountered significant challenges in obtaining pilot’s licenses and securing commercial flying roles. Unfazed, the resilient spirit of these female pioneers drove them forward, paving the way for future generations of women in aviation.

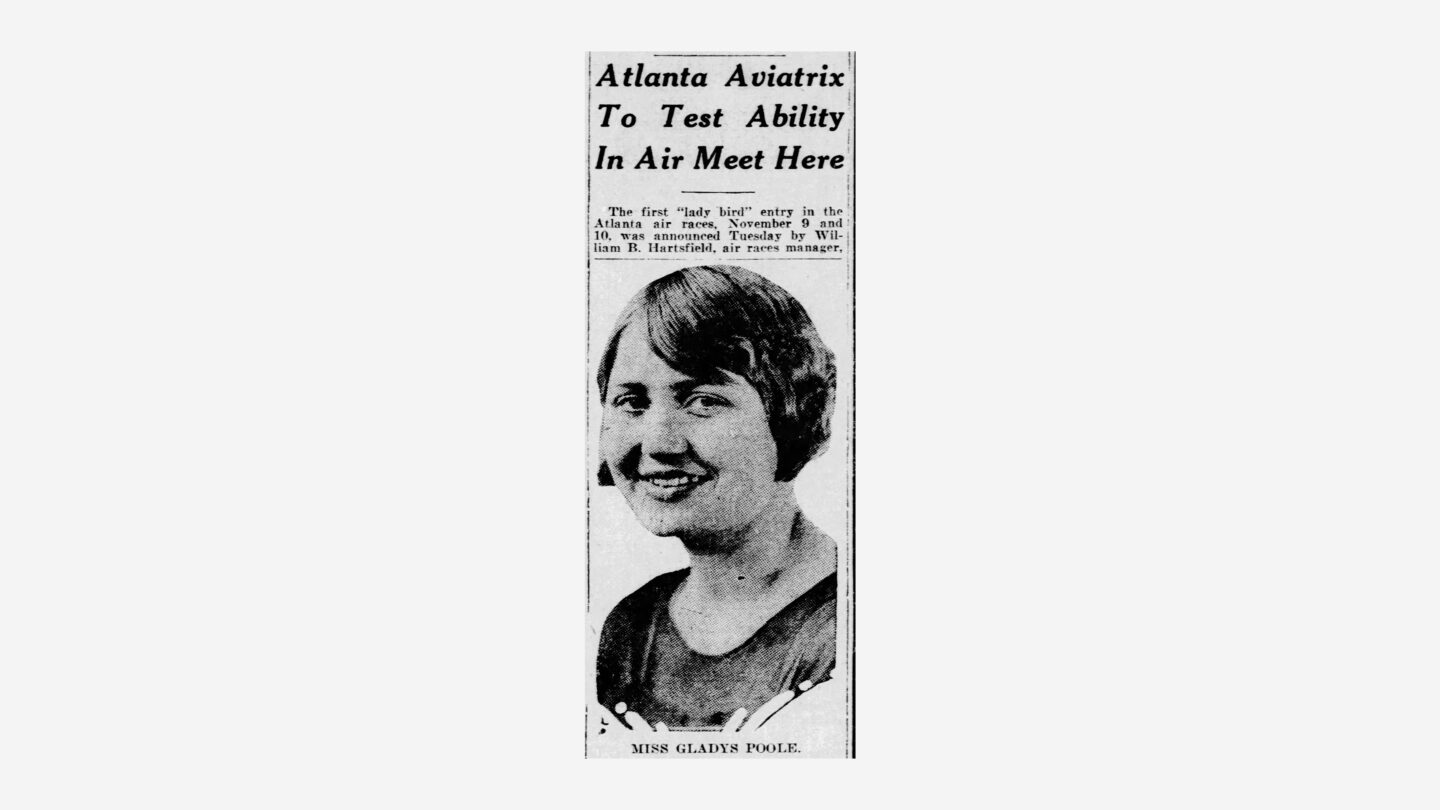

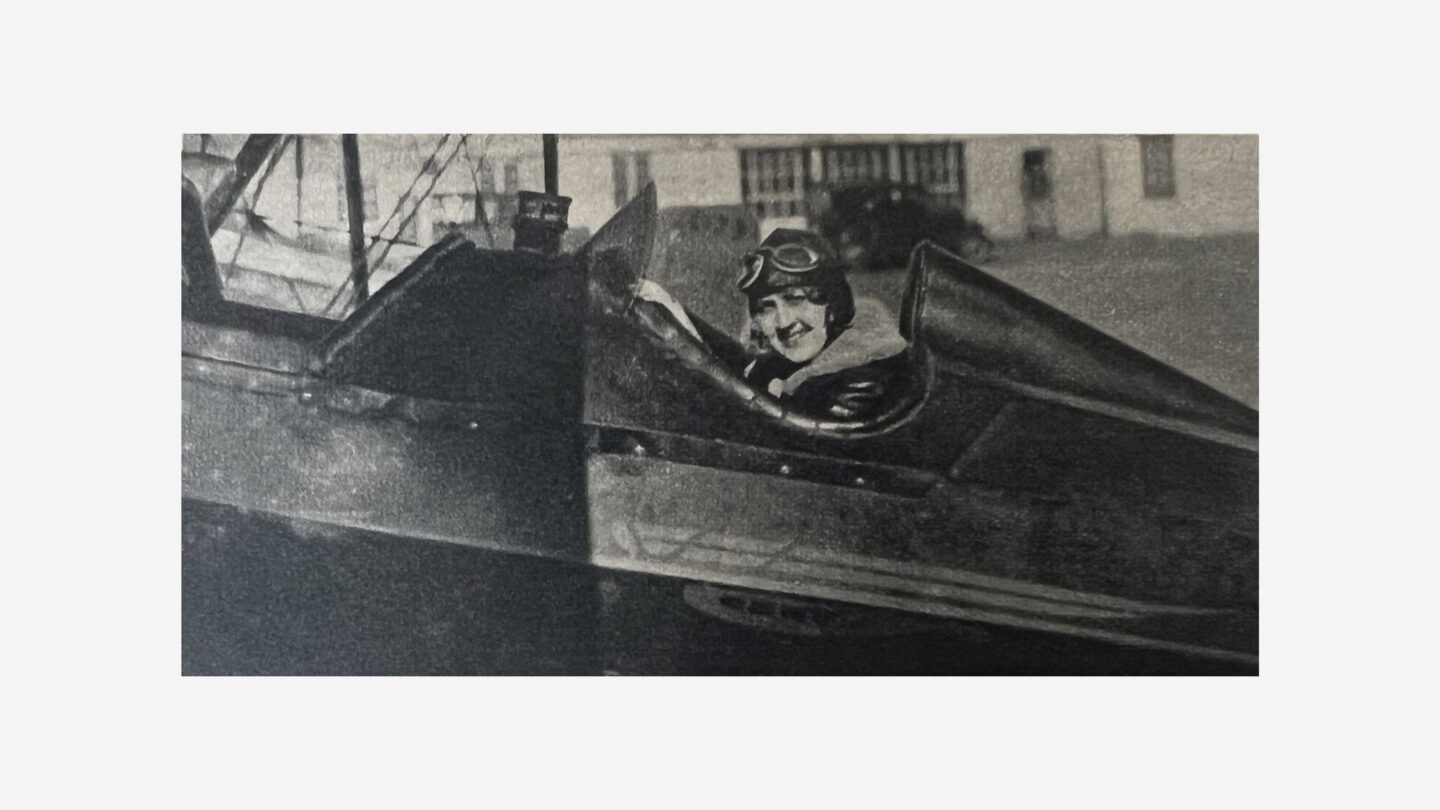

Gladys Poole, undated. Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine, March 22, 1964, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

Gladys Poole (1906–1991)

In 1927, Atlanta’s Gladys Poole joined Doug Davis’s flying school at Candler Field (now Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport). There, Poole discreetly took flight lessons without her family’s knowledge. When Poole’s father found out, he told Davis he’d allow his daughter to continue learning to fly if he could be her first passenger upon her licensure.

After her graduation, Davis invited Poole to work with him professionally as a barnstormer. These pilots would travel, captivating audiences with their aerial shows, though tragic accidents were frequent. Alongside Davis and other male pilots, Poole performed at aerial shows across the South, sometimes earning as much as $500 a week. She was recognized as the first licensed female pilot in Georgia and the South.

Poole had a passion for flying; outside of barnstorming and work, she spent time at Candler Field, piloting any available aircraft.

In 1929, Poole attempted an endurance test with a female-only crew of mechanics. She said this was the first plane prepared and checked by an all-female crew. Video of the event shows Poole and two female mechanics inspecting the plane in high heels before taking off.

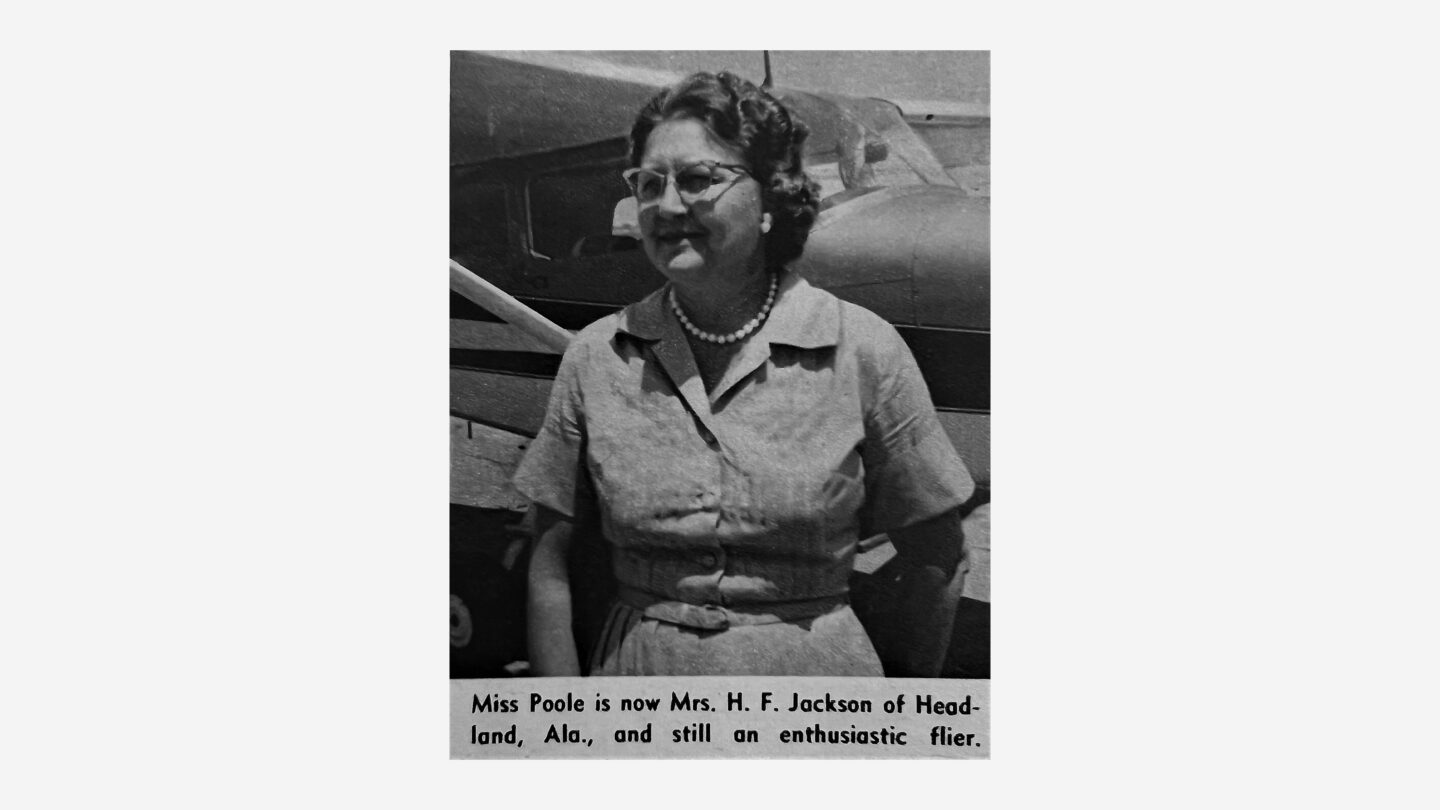

In 1934, Davis’s barnstorming crew disbanded as aviation shifted to passenger flights with an emphasis on safety. Without opportunities to fly for profit, Poole relocated to Miami for employment. There, she met and married Henry Forester Jackson, later moving with him to Alabama.

In 1964, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution Magazine profiled Poole, then known as Mrs. H.F. Jackson. She recounted her life during and after her barnstorming years. By that time, Jackson, in her 50s, only flew enough to keep her pilot’s license. She said flying more would bring back her “flying fever.” She lived out her life in Alabama and died in 1991, buried beside her husband.

Evelyn Greenblatt Howren, 1943. United States Army Air Forces

Evelyn Greenblatt Howren (1917–1998)

Gladys Poole paved the way for female pilots in Georgia. Evelyn Greenblatt Howren, an Atlanta native, was among them. Much like Poole, Howren concealed her interest in flying, taking her first flying lesson in 1939 as a Vanderbilt University student. Despite her parents’ strong opposition to her flying pursuits, Howren obtained her private pilot’s license in 1941.

She began her flying career in 1939, just before World War II. Though opportunities for female pilots were limited in the first half of the 20th century, the need for additional manpower during the war rapidly altered the aviation landscape. Howren was among eight women in the U.S. recruited for air traffic control with the Civil Aeronautics Authority at Candler Field. She soon became a Civil Air Patrol pilot.

From left to right, Eddie Collins, Evelyn Greenblatt, and Marjorie Gray while in WASP, Ellington Field, Texas, 1943. Cradle of Aviation Museum and Education Center

Before World War II, men transported aircraft and military supplies across bases, but when these men were shipped off to combat in Europe, women stepped in. Given Howren’s extensive flying experience, the U.S. Army Air Forces recruited her in its inaugural Women’s Airforce Service Pilots class. She served in WASP from 1943 to 1944. Although part of her service included training Army Air Force officers, Howren couldn’t join the regular Army Air Force because she was a woman.

After WASP disbanded in 1944, Howren’s flight career continued. Her father purchased a plane for her in Atlanta, and she worked as a flight instructor at Atlanta Municipal Airport. She teamed up with aviator Hillman V. Howren, who later became her husband, to open Flightways Inc. They ran the school from 1947 to 1968. Howren competed in the All Women’s Transcontinental Air Race in 1951. That year, she also earned the rank of captain in the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

Evelyn Greenblatt Howren photographed by Joann Vitelli, circa 1983. South Florida Sun Sentinel, November 11, 1983, via Newspapers.com

Because the U.S. government viewed former WASP members as civilian employees, they did not receive honorable discharges or veteran’s benefits. Howren and other former WASPs successfully lobbied Congress to grant all WASPs an honorable discharge in 1979. Howren was inducted into the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame in 1994. She died in 1998.

Janet Harmon Bragg, circa 1930. Smithsonian Institution Archives, RU 9545

Janet Harmon Bragg (1907–1993)

While WASP advanced opportunities for female aviators in the U.S., it excluded Black aviators, such as Janet Harmon Bragg.

A Griffin, Georgia, native, Bragg, attended segregated schools and later enrolled at Spelman College to study nursing. After graduating from Spelman’s nursing program in 1925, Bragg moved to Chicago, where she worked as a nurse. In Chicago, she noticed a billboard for the Aeronautical School of Aviation, which was also segregated.

She enrolled in the night school program at the Aeronautical School of Aviation while working as a nurse during the day. She was the only Black woman in a class of all Black men. Bragg faced sexism from her classmates but ultimately earned their respect.

Janet Harmon Bragg, Smithsonian Institution Archives Videohistory Collection, RU 9545 Black Aviators

After completing classroom training, she and her classmates needed flight practice to get their pilot’s licenses but lacked access to a training field. Bragg and her peers built a hangar in Robbins, Illinois, a Black community southwest of Chicago, to remedy this. She purchased an airplane for the training field with her earnings from nursing. Bragg wanted to join WASP when World War II began, but the organization denied her because of her race. She then sought a commercial pilot’s license; a certification no Black woman had achieved. She studied at Tuskegee Institute under Chief Anderson.

Bragg took her flight exam with T.K. Hudson, a white flight examiner. After landing, Hudson told Anderson, “She gave me the best ride I’ve ever had, [but] I’ve never given a Black woman a commercial license, and I don’t intend to.”

After being denied her commercial license, Bragg returned to Chicago, where she was able to obtain one in 1943, becoming the first Black woman to do so. She maintained her license for 35 years, flying regularly into the 1970s. She also championed aviation education and worked to expand educational and career opportunities for aspiring Black pilots.

“Aviator Janet Harmon Bragg, 86,” Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1993, via Newspapers.com

In addition to her efforts to expand access and educational opportunities for African Americans in aviation, Bragg and her husband, Sumner, managed two nursing homes in Chicago until their retirement to Tucson, Arizona, in 1972. In 1990, Bragg attended the inaugural symposium for Spelman Messenger magazine, where she discussed her experiences as a Black woman in aviation.

“The story of American Blacks in airspace largely remains untold,” Bragg said at the symposium.

“It mirrors American society, reflecting breakthroughs against a backdrop of [race and] exclusion. I’m not afraid of tomorrow because I’ve seen yesterday, and today is beautiful.”

Bragg died in 1993, but her legacy as an aviation trailblazer endures. The Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame inducted her in 2022.

The Pioneering Continues

Though women have been active in aviation for more than 100 years, they represent less than 20% of aviation-related jobs outside flight attendants. Women also constitute less than 5% of pilots in the U.S. Most of these female pilots are white. Black women account for only 3.4% of the 155,000 women employed as pilots.

However, flight continues to propel progress. In 1973, Bonnie Tiburzi became the first female pilot for American Airlines, a major American commercial airline. Cheryl Faye Peters became the first female pilot hired by Piedmont Airlines in 1974. She also captained a flight with the first all-female crew out of Atlanta in 1983. In 2019, Captain Andrea Lewis became the first Black female pilot in the Georgia Air National Guard. In a 2019 interview with the Black News Channel, Lewis said she hoped to inspire young minority girls to pursue piloting.