Our city’s LGBTQIA+ history is nuanced and vast—and too complex to be contained in a single story. While this article provides an overview of more than half a century of activism in our city, it is by no means exhaustive. To learn more about our ATL’s risk-taking change makers and historic moments beyond the Pride Parade, we encourage you to explore the Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing collection, the Georgia LGBTQ Archives Project, the Touching Up Our Roots oral history project, and other resources listed below this article. While we can’t be together this year, Atlanta History Center looks forward to celebrating with our community at 10th and Peachtree next October. Party on Pride.

For half a century, Atlanta Pride has provided a platform from which the city’s LGBTQIA+ citizens can voice their opinions and celebrate their community. Though it’s taken new forms over the years, Pride’s mission has remained the same: to advance unity and visibility amongst Atlanta’s LGBTQIA+ community. This year is no different—Atlanta Pride is once again seeking to amplify the messages of our city’s LGBTQIA+ community, making history by going virtual.

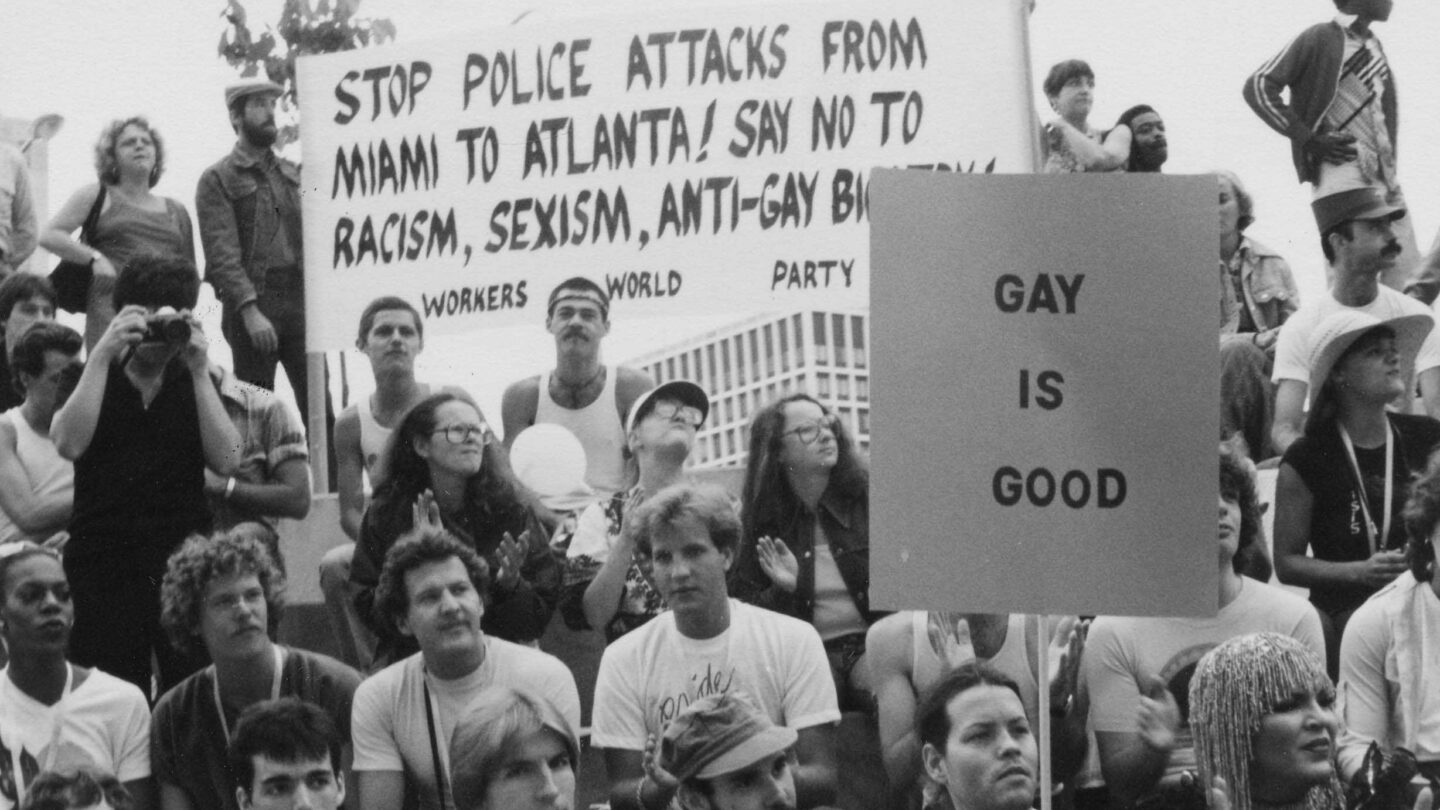

Pride was born from protest. Last year marked the marked the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising, which sparked national media attention for America’s LGBTQ rights movement. The protests in New York on June 28, 1969, proved to be the catalyst for communities across the country, inspiring protest, mobilization, and change. In Atlanta, the Lonesome Cowboys raid of August 1969 sparked similar outrage from the LGBTQIA+ community across the city. That year national tensions were high from the Vietnam anti-war movement and from the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as Atlanta’s central role in the Civil Rights Movement. Within that environment, the city’s LBGTQIA+ organizers saw an opportunity for visibility and change.

As it often does, the present echoes the past. The militant actions of Atlanta Police in August 1969 galvanized the city’s movement and led to the foundation of the Georgia Gay Liberation Front, Atlanta’s first gay activist group to gain political traction. They were responsible for the organization of the city’s first Pride demonstration—a small tabling event in Piedmont park where a handful of activists distributed leaflets—held in 1970. In June 2020—National Pride Month—Pride rallies once again responded to police brutality, even though in-person celebrations were cancelled amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement. Throughout Atlanta, marches honoring black transgender and nonbinary people killed by police threaded the city. Protesters carrying “Black Trans Lives Matter” signs joined the Georgia NAACP march, culminating at the State House on June 15, 2020. Marches honoring Tony McDade and Nina Pop superseded annual celebrations, and “Pride was a riot” became a popular refrain among demonstrators.

Demonstrators honoring Tony McDade march past Margaret Mitchell House on June 7, 2020 on their way to rally in Piedmont Park.

In its 50th year, Atlanta Pride, celebrated in October, remains one of the foremost gatherings of LGBTQIA+ activists in the country. As the city gathers (distantly, virtually) to once again to chart its future, we invite you to examine Pride’s past.

Pride for the People: Origins of the Movement

Pride in Atlanta during the 1970s and 1980s focused on forging a path for LGBTQIA+ activists. The aims of parade and rally organizers were to seek out opportunities for policy change, to form a sense of unity within the community, and to build a network of outspoken supporters to serve as a hub for LGBTQIA+ rights in the South. To do this, organizers sought to create new traditions through Pride parades, rallies, and publications.

Atlanta’s first Pride event (though it wasn’t labeled as such) took place in 1970 on the first anniversary of the Stonewall uprising in New York. Organizers worried that, in that inaugural year, too few people would choose to march, so they opted for tabling in Piedmont Park. This small act of protest sent ripples through the city’s gay community. The following year, the Georgia Gay Liberation Front organized Atlanta’s first Pride parade. Around 100 demonstrators—mostly white males—marched down Midtown’s sidewalks carrying “Equal Rights for Gays” posters. The march ended at Piedmont Park where a rally took place.

Fast forward six years to 1976 and the crowd swelled to more than 1,000 people at Atlanta Pride, but it remained predominantly white and male. Mayor Maynard Jackson declared the day of the parade, June 26, to be Gay Pride Day in Atlanta. The following year, Mayor Jackson issued a subsequent proclamation for Civil Liberties Day after facing backlash for his emphasis of Gay Pride in 1976. This galvanized the city’s LGBTQIA+ community in 1977. Attendance of that year’s parade skyrocketed. Activist Larry Laughlin wrote in The Barb, “If the [1977] March did nothing else but show other gays our potential, it was well worth the effort.” (In 1993 Jackson proclaimed the full week of June 21-27 “Lesbian and Gay Pride/Human Rights Week” in Atlanta—the manuscript for which is housed at Atlanta History Center’s Kenan Research Center.)

Local activist Bill Murphy recalled his first Pride experience as a Georgia Tech student in Atlanta in 1976 during an interview with the Atlanta Journal Constitution: “[Marching down Peachtree] was a dangerous thing to do. … All these things were running through my mind: What if one of my classmates sees me? What if a carload of rednecks drives into us?” Despite the fear, Murphy felt hopeful.

“At the same time, it was exhilarating. It was an incredible feeling of not being alone anymore.”

In 1979, Pride went aquatic with the Hotlanta River Expo. Though not a part of the official Atlanta Pride Parade, Hotlanta River Expo’s inaugural year attracted more than 300 gay men rafting down the Chattahoochee River. By 1989, the event had grown into one of the largest gay events in the Southeast. It became so popular that it had to be extended over four days and expanded to include multiple parties, competitions, and the annual Mr. and Miss Hotlanta Pageants.

Back on land, Atlanta Pride officially became Atlanta Lesbian, Gay, and Transperson Pride in 1980. The following year, Lesbian, Gay, and Transperson Pride Week was celebrated locally by an estimated 3,500 participants. Programming expanded beyond the traditional parade and rally to include a live concert, radio show, art show, film festival, history symposium, block party (on 7th Street between Piedmont Avenue and Juniper Street), voter registration drive, and an open house for the city’s Atlanta Gay Center and Atlanta Lesbian Feminist Alliance headquarters.

By the late 1980s with the rise of the AIDS epidemic, Pride’s mission began to pivot toward public health. The theme for Atlanta’s 20th annual Pride in 1990 was Be There, Be Aware, Be Counted. Over 10,000 people marched for 15 blocks to join another 20,000 at a rally in Piedmont Park. Around 500 people attended a mass candlelight vigil for Atlantans who had died of AIDS.

It was a landmark year for Atlanta Pride in terms of attendance and press coverage. Both the Atlanta Journal Constitution and Creative Loafing featured cover stories on the week’s events, including a mass commitment ceremony joining 83 LGBTQIA+ couples. The celebration’s first craft market and the Gay Pride Run/Walk were included in 1990.

By 1994, an estimated 150,000 attended Atlanta Pride, making it the fifth largest in the nation.

Although a gathering of African American lesbians and gay men in Piedmont Park had been a tradition for more than a decade, 1997 marked the first official Atlanta Black Gay Pride event. Today, Atlanta Black Pride is an entire week of performance, demonstration art, college fraternity reunions, as well as a film festival, literary café, and health and lifestyle expo.

Celebrating in the New Millennium: Pride in the 2000s

The 2000s ushered in a new generation of Atlanta Pride participants. The celebrity of headlining music acts at the annual concert in Piedmont Park increased over time. Athens locals, The B-52s, played at the 30th annual Atlanta Pride celebration in 2000. The Indigo Girls headlined in 2005 and played to a crowd of over 320,000.

Corporate involvement also grew. In 2000, Coors, Pepsi, Jose Cuervo, Stolichnaya, and Showtime donated an aggregate $250,000 to cover festival costs. Today, Atlanta Pride’s sponsors range from hometown companies Coca-Cola and Delta Air Lines, to international brands, such as Smirnoff.

In 2009, the organizing committee elected to reschedule Pride from its traditional date in June to October. The decision was made to keep crowds out of the heat and have the celebrations coincide with National Coming Out Day on October 11.

Be a Part of History

While we can’t physically come together this year, that doesn’t mean we can’t celebrate. Atlanta History Center invites you to be a part of history by sharing your stories with the Atlanta Corona Collective. We are collecting materials that illustrate how people are experiencing and responding to all aspects of life in Atlanta during the COVID-19 crisis—including the ways in which you protest, party, and show Pride. No matter where you are in the Atlanta region, we want to hear from you. Learn more about how to share your stories, images, and objects with us at the Atlanta Corona Collective submission page.

Curious to know more about our city’s LGBTQIA+ history? We’ve got you covered. Atlanta History Center is proud to host the Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing, the city’s first repository for queer history and the cornerstone of our LGBTQIA+ collection. The ALGHT is a collection of papers and publications related to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community of Atlanta. It includes the personal papers of Atlanta activists as well as local gay newspapers and magazines, public health pamphlets, travel guides, and community publications. The collection is housed onsite in Atlanta History Center’s Kenan Research Center, at our Buckhead location. To start your search through our plethora of LGBTQIA+ collections, browse our finding aids online.

We also recently digitized The Barb, one of Atlanta’s first LGBTQ newspapers. The entire publication (1975-1977) is fully text-searchable and provides invaluable insight into the daily lives of our city’s queer pioneers.

We invite you to explore the collection and learn more firsthand history for yourself.

All are welcome.

Interested in further reading?

- Out in Atlanta: Atlanta’s Gay and Lesbian Communities Since Stonewall: A Chronology, 1969-2012 | Wesley Chenault

- Gay and Lesbian Atlanta | Wesley Chenault and Stacy Braukman

- Terry Bird Collection of Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing, Inc. Records | Georgia State University

- Richard Rhodes Papers | Georgia State University

- GLBTQ encyclopedia entry for Atlanta | Tina Gianoulis

- From Whence We Came: Our LGBTQ ATL History | Berlin Sylvester

- Portrait of a community: An LGBT Atlanta timeline | GA Voice

- Celebrating 44 years of Atlanta Pride and who we are | GA Voice

- Pride: Atlanta festival celebrates its 37th year | Atlanta Journal Constitution

- Annual Atlanta Pride Festival: The Early Years | Atlanta Journal Constitution