Jacques and May Futrelle in a 1909 automobile tour sponsored by the Atlanta Journal and New York Herald in Atlanta. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

In early 1912 Georgia-born author and journalist Jacques Futrelle traveled to Europe to promote his Thinking Machine stories and to gather inspiration for future works. The Thinking Machine was a series of detective stories featuring Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen, a brilliant logician who solved complex mysteries with his superior intellect, often considered an American version of Sherlock Holmes for his deductive prowess and analytical methods.

Traveling alongside Jacques was his wife, Lily May, an author and journalist from Atlanta known for her bestselling novel Secretary of Frivolous Affairs. After securing new contracts with upfront cash advances, the Futrelles yearned to be back at home with their children, Virginia and Jacques Jr.

Days before the couple was to leave Europe, Jacques celebrated his 37th birthday, and in a narrative twist worthy of Jacques' own stories, they were offered passage on the RMS Titanic, an ocean liner making its maiden voyage to New York City. As they embarked on this ill-fated voyage, the Futrelles were unaware that their names would soon be etched in history for their literary achievements and as part of a maritime disaster.

"Titanic Disaster." Globe Film Company, Warner's Features, and Kleine. Library of Congress

As first-class passengers on the Titanic, Jacques and May mingled with members of the American elite, from business magnate John Jacob Astor IV to theatrical producer Henry B. Harris. On the night of April 14, 1912, Jacques and May attended a lavish dinner party with Harris and his wife before retiring to their stateroom. May would later recall that she and Jacques had been "filled with the joy of living" that evening.

At 11:30 p.m., the couple heard a loud sound, but Jacques dismissed the noise as harmless. Soon after, alarms began to sound, and passengers were ordered to begin evacuation procedures. First-class passengers were all told to gather in the saloon to put on life jackets.

The Titanic’s crew began lowering lifeboats, and female passengers and children were allowed to board the vessels first. During the evacuation, the prioritization of women and children led to the painful separation of families, with May being separated from Jacques during the chaos.

Jacques, displaying stoic bravery, insisted that May get on a lifeboat and save herself for their children's sake. Jacques' calm demeanor marked the couple’s final farewell. When May last saw her husband, he was sharing a cigarette with Astor on the promenade deck as the ship sank.

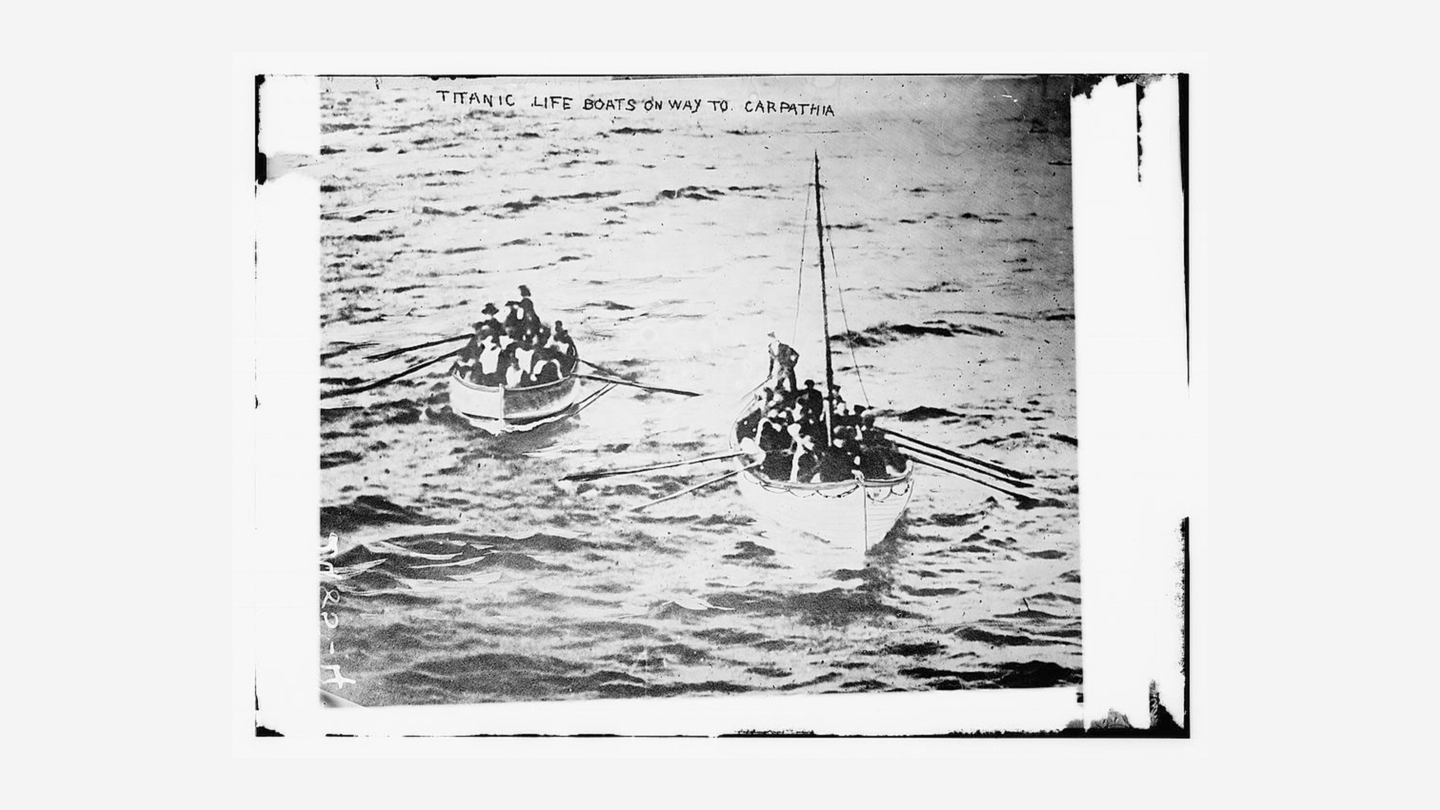

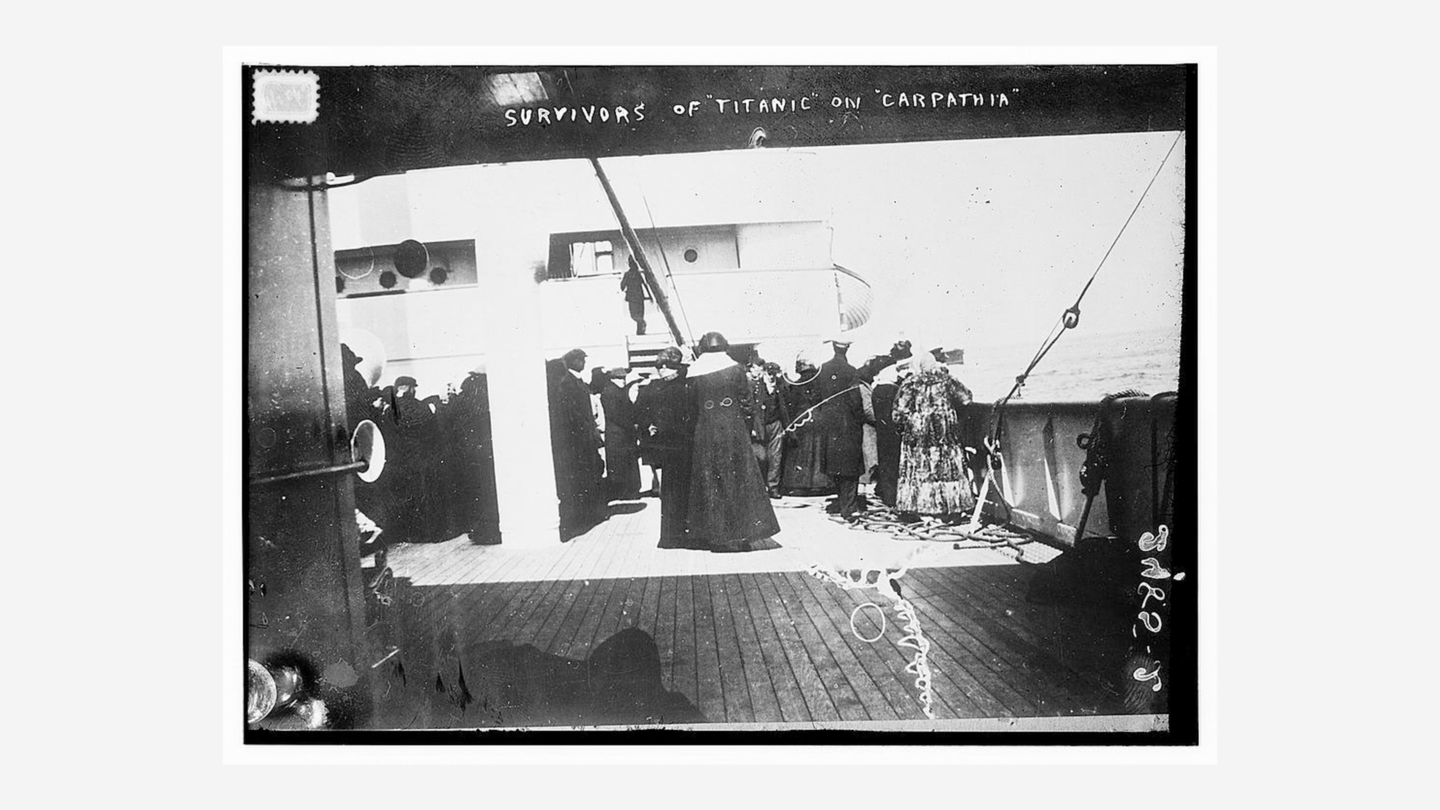

May and those in her lifeboat languished in the Atlantic for four hours until the RMS Carpathia arrived. When the crew on the Carpathia received the Titanic's distress signals, they traveled at full speed from their location 58 miles away to reach May and other survivors. Of the 2,240 passengers and crew on the Titanic, only 700 survived the disaster. The Carpathia was the only ship to rescue surviving passengers.

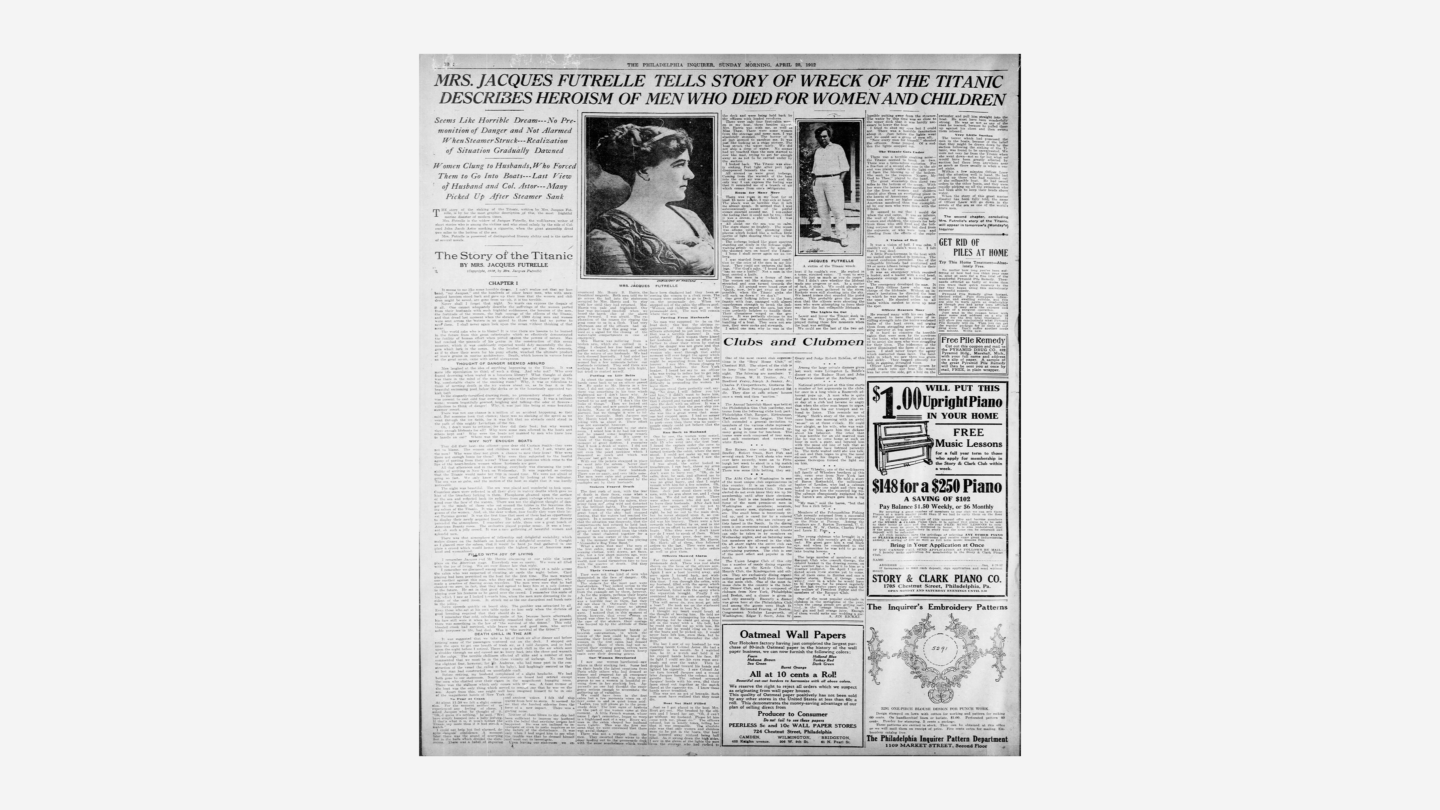

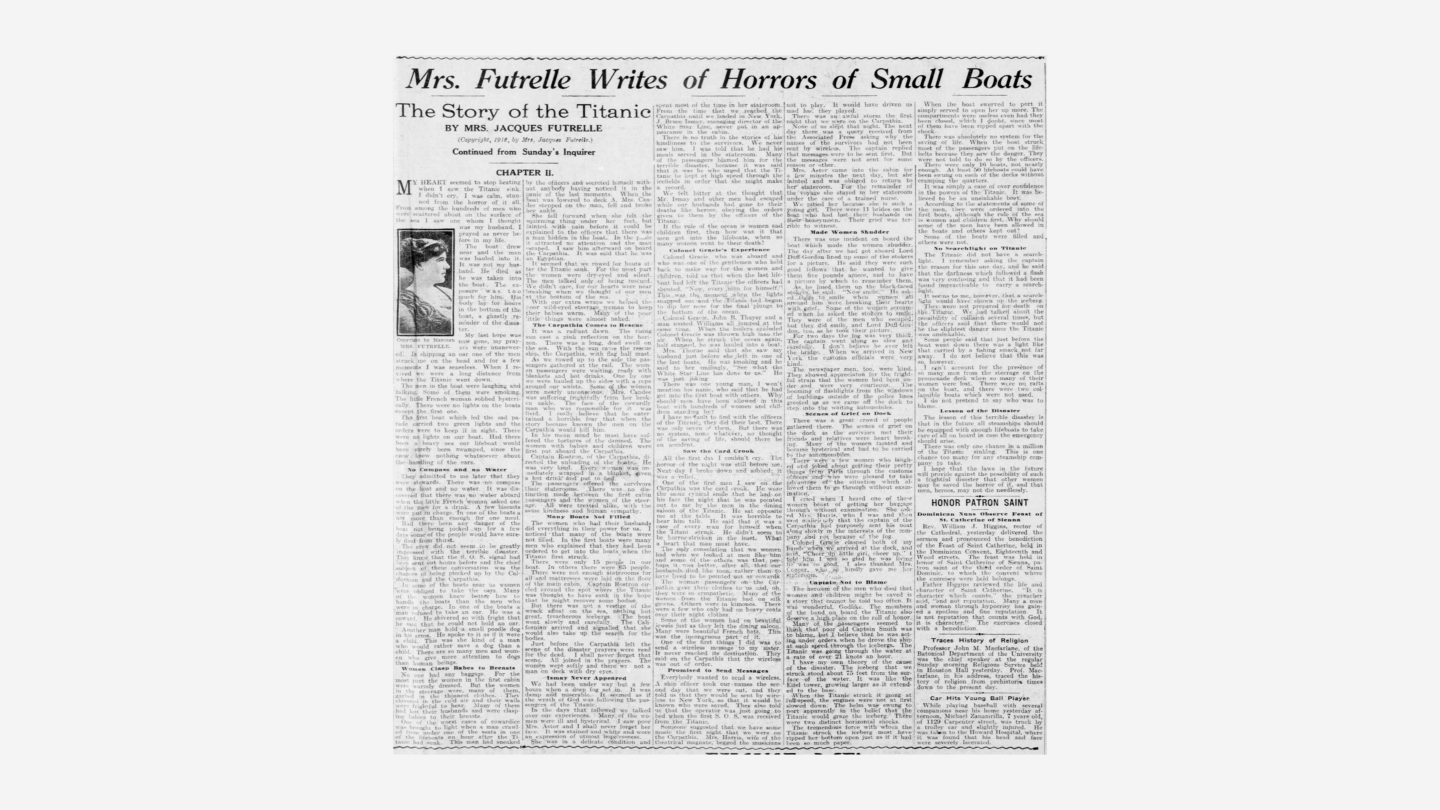

On April 28, 1912, The Philadelphia Inquirer published an article that May wrote about her harrowing experience on the sinking Titanic. Later in life, May gave lectures about the Titanic disaster, even inspiring artists with her descriptions of the sinking ship. Though journalists over the years quoted May in their articles, they missed a crucial detail in her written account: she said the Titanic broke in half before it sank beneath the waters of the Atlantic.

"It was a pitiful spectacle that the great ship presented," she wrote. "Her back was broken in two, she was like a great worm that someone had stepped upon. I had no sooner reached the deck, than she began to list to port—even then there was no panic—people simply could not believe the Titanic could sink."

May was not the only survivor who testified that the ship broke in half as it sank. Other survivors, including Eva Hart, who was 7 years old at the time, recounted this detail when interviewed by the British Wreck Commissioners. However, because most of the survivors were women and children, their words were dismissed as hysterical reactions to a traumatic event.

Today, we consider the fact that the ship broke in half one of the most memorable aspects of the disaster. The scene was even recreated in James Cameron’s 1997 Titanic film. But in the decades between the Titanic’s sinking and the discovery of its remains in 1985, this detail was contested and denied by many official sources, including those that determined the future of nautical safety.

For example, the 1912 Titanic Disaster Report from the United States Senate Committee on Commerce concluded that the ship sank intact while dismissing survivors’ testimonies as conflicting statements:

"There have been many conflicting statements as to whether the ship broke in two, but the preponderance of evidence is to the effect that she assumed an almost end-on position and sank intact."

“Titanic Sinking,” engraving by Willy Stöwer. Willy Stöwer, 1912, Library of Congress

Not all survivors’ testimonies were considered equally. Charles Lightloller, an officer on the Titanic, survived by diving off the boat when an underwater boilerplate exploded and pushed him to the surface near a lifeboat. He insisted that the Titanic sank intact.

“Her stern was gradually rising out of the water, and the propellers were clear of the water,” he testified to the British Wreck Commission.

“The ship did not break in two; and she did eventually attain the perpendicular, when the second funnel from aft about reached the water. There were no lights burning then, though they kept alight practically until the last. Before reaching the perpendicular when at an angle of 50 or 60 degrees, there was a rumbling sound which may be attributed to the boilers leaving their beds and crashing down on to or through the bulkheads. She became more perpendicular and finally absolutely perpendicular, when she went slowly down.”

While this issue may seem trite from a modern perspective, it must be emphasized that the British Wreck Commissioners were holding an inquiry to assess what caused the Titanic to sink and how to prevent future disasters. By prioritizing Lightloller’s account over the accounts of others, including women and children, the commissioners sabotaged their own efforts to increase nautical safety.

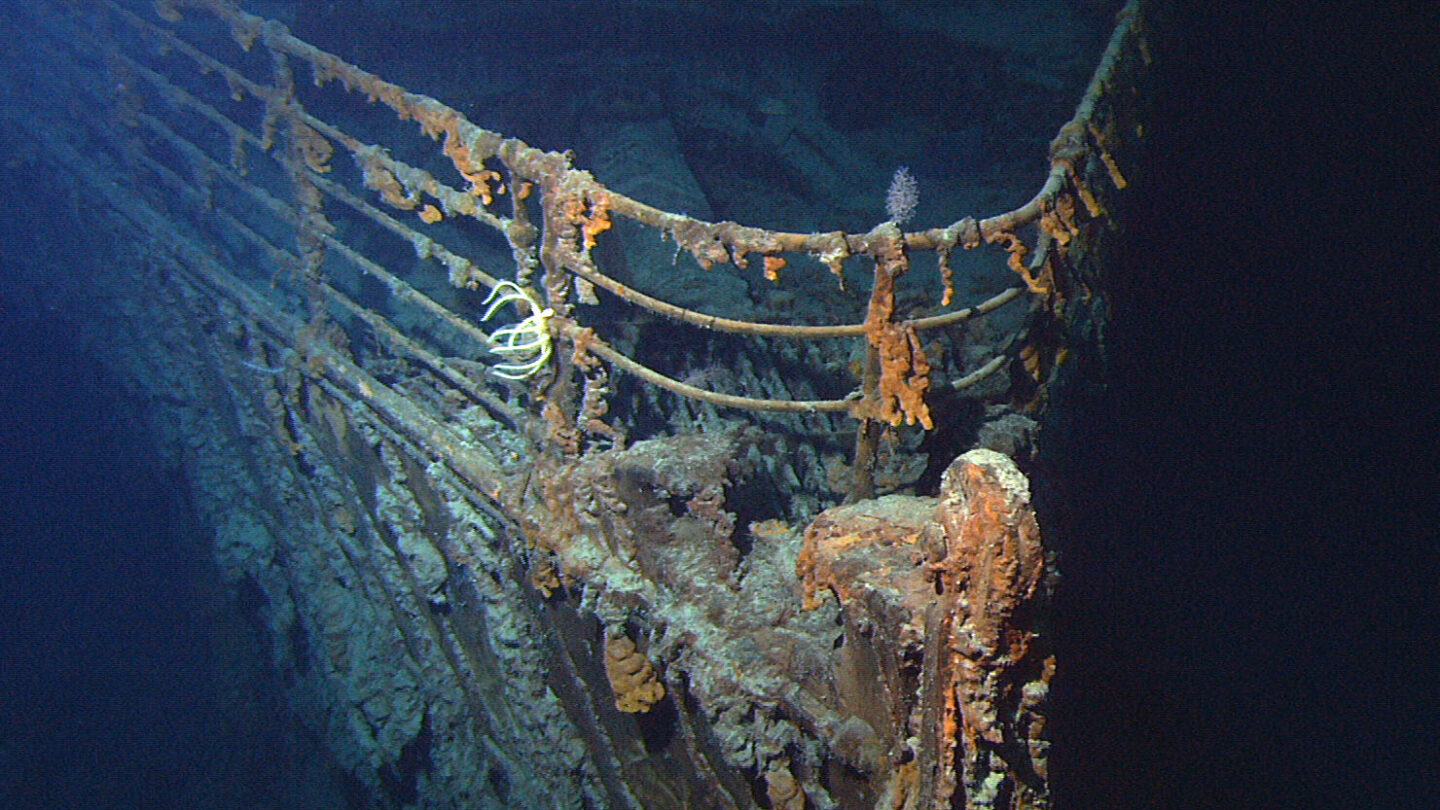

View of the bow of the RMS Titanic photographed in June 2004 by the ROV Hercules during an expedition returning to the shipwreck of the Titanic. NOAA/Institute for Exploration/University of Rhode Island

The issue was settled once and for all on September 1, 1985, when Robert Ballard and Jean-Louis Michel located the wreckage of the Titanic. The ship split in two as it sank. However, this didn’t mean that May or other survivors would immediately be given their rightful due. In fact, in the onslaught of newspaper articles that followed this historical discovery, only a few of them acknowledge that survivors had already known what happened to the ship before Ballard’s and Michel’s discovery. The only one that refers to any survivors by name (in this case, Eva Hart) was a 1995 Standard Star article that reviewed film depictions of the Titanic disaster.

How and why the ship broke in half puzzled researchers for years. In 2008, Brad Matsen published his nonfiction novel Titanic’s Last Secrets. One of the mysteries the book sought to answer was why the ship split in half the way it did.

“Contrary to all accepted theories, [naval forensic experts] concluded that the Titanic’s stern did not rise out of the water at a steep angle and then break apart. The Titanic flexed near mid-ship after hitting the iceberg, they concluded because the structural integrity of the ship was not what it should have been. […] The ship broke in half on the sea’s surface, then it sank. The materials were neither of the quality nor mass required by a ship of the Titanic’s size. The original specifications of its designer, Thomas Andrews, were not followed in order to reduce the cost of building the ship, they suggest.”

The fact that the ship split in half turned out to be a crucial part of how ill-conceived the Titanic’s construction was. Imagine how much faster these conclusions could have been reached had survivors such as May been believed from the start. With this information, White Star Line might have been forced to acknowledge much earlier the part that their negligent business practices played in the Titanic disaster.

Portrait of Lily May Futrelle. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Decades after her death, May's contributions to the Titanic's narrative were largely overlooked in media coverage. Few articles acknowledged her significance. One piece mentioned her in the context of passengers whose personal belongings were found at the Titanic's wreck site. Another article recounted the stories of Titanic passengers from Atlanta, referencing May's Philadelphia Inquirer article but omitting her controversial observation of the ship splitting in half. Yet another article mentioned her legal battle with the White Star Line over her husband's death and their lost possessions, but again, her broader influence on the Titanic's legacy was neglected.

May's references in media were typically tied to her husband's tragic death, yet her broader impact deserves recognition. Unlike Eva Hart, May did not witness her account being publicly validated. Her story is often excluded from discussions about Titanic survivors with disputed narratives. Nonetheless, May's bravery stands out. She firmly maintained her account of the events and shared her perspective in a newspaper, contributing significantly to the historical understanding of the Titanic's fate.

Further Reading

Jacques Futrelle Papers—This collection of papers at Kenan Research Library at Atlanta History Center consists of manuscripts and published copies of stories, programs for plays, information about Jacques and May Futrelle, and some family information.

Project Gutenberg —Works by Jacques Futrelle showcasing popular titles such as The Problem of Cell 13, Elusive Isabel, and The Chase of the Golden Plate.

LibriVox—Free public domain audiobooks of some of Jacques Futrelle’s works.