Maynard Jackson, 1974. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

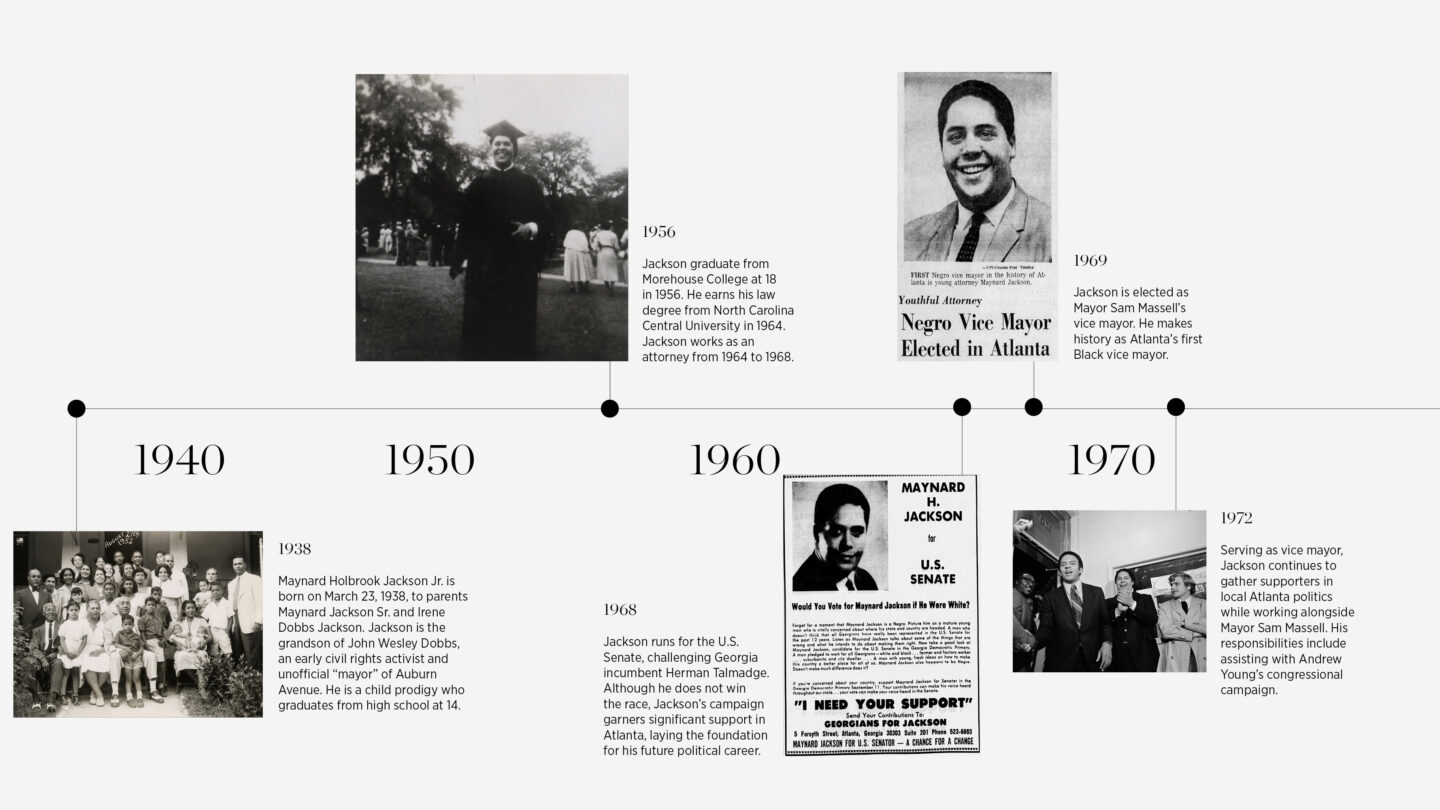

Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr. was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1938, but his life’s journey led him to Atlanta at the tender age of 8, where he established deep roots in Georgia. His family had a significant impact on the state’s history, with his grandfather, John Wesley Dobbs, being the founder of the Georgia Voters League. Notably, his mother made history as the first African American to possess an Atlanta public library card, and his aunt Mattiwilda Dobbs achieved the distinction of being the first African American to perform at La Scala, an opera house in Italy.

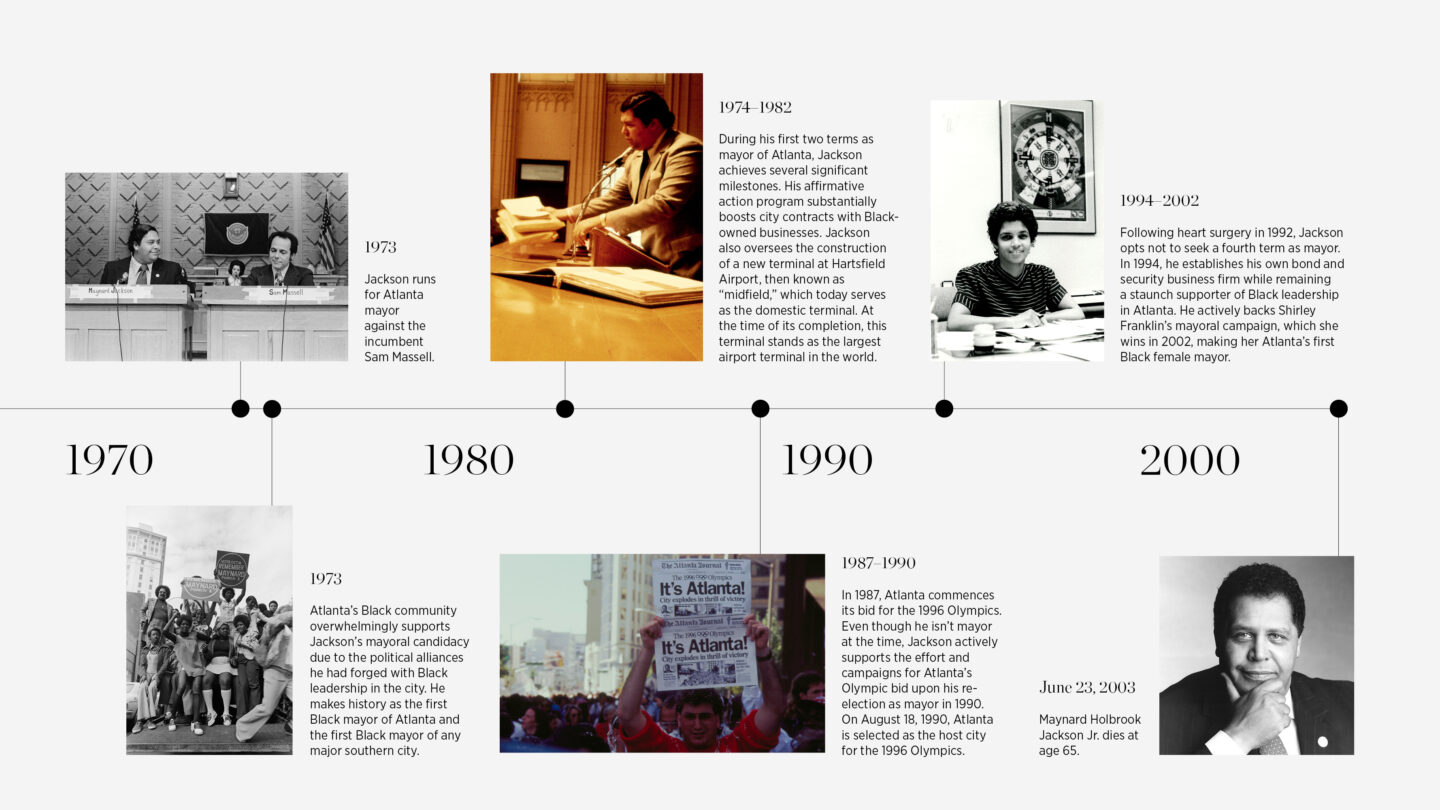

At 30, Jackson ventured into Georgia politics, albeit unsuccessfully, when he ran for Herman Talmadge’s U.S. Senate seat. However, his defining moment came in 1973 when he challenged incumbent Mayor Sam Massell for the mayorship of Atlanta. In a racially polarized election, on October 16, 1973, Jackson emerged victorious with an impressive nearly 60 percent of the vote, making him Atlanta’s first Black mayor at 35—a pioneering achievement for a major southern city. His victory was a result of strong support from a diverse coalition that included white liberals, moderates, and African Americans.

In 1974, Jackson began his term as Atlanta’s 54th mayor. He served in the role from 1974 to 1982 and later returned as the 56th mayor from 1990 to 1994. A dedicated member of the Democratic Party, Jackson’s enduring leadership spanned three terms, placing him second only to the six-term Mayor William B. Hartsfield in the annals of Atlanta’s mayoral history.

Jackson’s legacy extends far beyond his election. During his tenure as mayor, he increased the representation of Black police officers, championed minority contractors to receive more city business, and achieved the on-time and under-budget completion of a new terminal at Hartsfield International Airport. As Atlanta celebrates the 50th anniversary of Maynard Jackson’s historic mayoral election, we invite you to join us in paying tribute to his enduring legacy on this momentous occasion.

Maynard Jackson graduates from Morehouse College, 1956. Amistad Research Center, Tulane University

Drawing from exclusive interviews and archives, we present Maynard Jackson’s own words on the influences that shaped him, his remarkable journey to becoming mayor, his deeply held beliefs, and the wisdom he imparted throughout his life. Through his own words, we can gain a profound understanding of the man behind the historical milestones, offering a unique and intimate perspective on his enduring legacy.

Early Influences.

On upbringing and decision to get involved politically, 1988.

“I am descended from three generations of Baptist ministers, and if anything, I felt I may have been destined to go in the ministry. In fact, I think I had almost decided to do that before my father died when I was 15. I had gone to Morehouse when I was 14 as a freshman [in] an early admissions program for the Ford Foundation Scholarship. And [my father] died when I was 15, and luckily, I was surrounded by the value system that my father and mother felt was important. I decided not to go [into] the ministry. I began to think about what I could do to apply what I felt were certain talents in another direction that might have a similar benefit. And I decided to become a lawyer because I could use [my] skills as a lawyer to change the law to make things better that way. And I did so as an attorney for the poor for many years. Friends of mine in Cleveland, where I waited tables in the late ’50s and sold encyclopedias door-to-door, tell me that they remember my saying then that I intended to run for mayor of Atlanta. I have no recollection of that. But I will tell you that whatever may have been my feelings early on, I’ve always known that I was destined for some sort of public service.”

Political Journey.

“Youthful Attorney, Negro Vice Mayor,” October 8, 1969, Courier Post via Newspapers.com

Becoming first Black mayor of Atlanta and running against Sam Massell, 1988.

“Being the first Black mayor is what you wish on your enemy, okay? And I say that with tongue in cheek. A great pride to be mayor of Atlanta, and every Black mayor who’s been the first Black mayor of America, I’m sure, has felt the same thing. But it truly is part hell. You, first of all, start with exaggerated Black expectations that overnight, Valhalla will be found, heaven will come on earth, and it’s all because the Black mayor’s been elected. And things just don’t work that way. The obligation that I felt was to try, with everything in my power, in every legal and ethical way that I could, to move things as quickly as possible in that direction. But meanwhile, having to explain to somebody who called me from Ludowici, Georgia, that no, I really was not their mayor. I’d be very pleased to help if they didn’t mind my waiting a little while because we’re getting 450 phone calls a day. Right? Even from out of state. All of a sudden, I became the mayor not just of Atlanta, but of Black people in Georgia and even some neighboring states. That was an extraordinary burden.”

Core Beliefs and Principals.

Congressional candidate Andrew Young, center, enters his campaign headquarters on election night as Atlanta Vice Mayor Maynard Jackson, second from right, looks on, 1972. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

“This is an America where the most perfect revolutionary act in this democracy is voting. Black elected officials have all of the challenges that white elected officials have, with a major overlay in addition. That overlay is to prove–we shouldn’t have to do this, it’s not fair that we’re asked to do this, it’s not fair that we’re expected to do this– ourselves more than others. Not just to white, the white community but to the Black community as well. There is an undercurrent in Black America that fears that Black elected officials will embarrass the Black community. One of the things that I’ve sworn I would never do is to do anything that would embarrass my city. Anybody, Black or white, but especially the Black community.”

On electing people who know what prize they are after, 1988.

“The prize is equal opportunity. It is good management. It is a better way and a better day. It is a change from the status quo. And the prize also is to serve well and to serve fairly, to serve honestly, but to make a difference. And if the only thing one is doing is holding office, saying, ‘Hi, look at me, I’m a Black elected official,’ and then not taking care of business. If they’re not using the power they have to change things for the better, they are a waste. The prize is a better way and a better day for all people, especially those who are oppressed.”

“Politics is not an end; it’s a means to an end. It is a means of changing public policy, and public policy controls almost every aspect of our lives. And we are the change agents. It is through us the people speak, ‘We want this, we want that, this kind of life, this kind of quality of life.’ And we must deliver. Honestly, fairly to all people, but we must deliver.”

Triumphs and Trials.

Mayoral candidates Jackson and Massell in run-off debate, 1973. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

1968 Jackson conceding to Talmadge.

“My candidacy, if it has done nothing else, has shown clearly that in Georgia, there is a chance for a change. It is a change from the old politics, the unresponsiveness, to setting an example of possibility for the entire nation.”

“I think there has been a very significant victory here tonight in Georgia. It is a victory because we have set an example of possibility for the entire nation by showing that here in Georgia, a race can be run by a man who had no prior political experience, by a man who is Negro, a man who campaigned throughout the entire state, who was well received, who was shown respect wherever he went.”

“It was, in most cases, with teeth gritted and doing not more than the letter of the language required. And even then, there was resistance in every conceivable way by certain contractors. Not by all of them. Some contractors said this is a reality; whether I like it or not, I’m going to deal with it, make the best out of it, and establish relationships, so they were willing to do so. We had a company that resisted—I mean, it just became their passion to fight this all— they threatened us with everything they possibly could think of and went on. And we just said, ‘Okay, you know, if you want to do it, you want to go to court, fine. We’ll see you in court, but we’re not going to back off on this policy because it’s right and because it is a means and the most effective means we can think of at this point, by which we can correct the wrongs of the past.’ That does not mean extra compensation. It means if the law and if the policies and the practices leading up to the time that we came into office were wrong, racist, unfair, and all the other kind of stuff, all the other kinds of negative descriptions, that had to be corrected. And not just—when we say ‘the whites,’ just be sure that you understand, I keep bringing it back to this point, it’s important to remember this: The white community was not and is not monolithic.”

Affirmative action success, 1988.

“When I became mayor, 0.5 percent of all the contracts in the city of Atlanta went to Afro-Americans. In a city which, at that time, was 50-50 and today is about 70 percent Black. There were no women department heads. This was not only a question of race, it was a question also of sexual discrimination and, you know, all the typical isms. If there’s one, normally there is a whole bunch of them, and they were all there. We had to change dramatically how the appointments to jobs went, normal hiring practices in city government went, the contracting process. Not to reduce the quality, by the way, ever. We never, ever, ever set up a lower standard. And those who say, ‘Well, affirmative action means you’ve got to lower the standard,’ that’s a real insult, in my opinion, to African Americans and other minority Americans. We never did it, didn’t have to do it. We built the Atlanta Airport, the biggest terminal building complex in the world, ahead of schedule and within budget, and simultaneously rewrote the books on affirmative action. Atlanta airport alone accounted for 89 percent of all of the affirmative action in America, in all of America’s airports, and the FAA told us that.”

Behind the Scenes.

Supporters hold up campaign signs for Maynard Jackson, 1973. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

“I would go, and I would—well, I’d—just almost every legislative session; I think I missed maybe a couple of them, but I mean, the opening day that I was at every legislative session at one time or another while I was in office, and say ‘hi’ to people, let them know that we very much appreciated what they were doing. We beefed up our lobbying action, hired, for the first time, a full-time lobbyist over there, had a table set up in the state capitol to handle the problems of legislators, whatever they were, okay? And you know, they wanted tickets for 30 school kids to go to Atlanta Zoo; they got them for free.”

What Jackson was like behind the scenes meeting with business leaders, 1988.

“I made my share of mistakes. I must tell you that I am not limitless in my patience… And after a while, I feel like I’m running after folks to, hey, you know, say, ‘Hey, look at me.’ But if it gets to a point that I feel like I’m kind of beginning to scrape and bow to be accepted, I’m not prepared to go that far. I was right at the edge on that, right up at the edge. I’ve bit my tongue many a time. It’s all about pride, many a time. But never wrote off the business community. But some of them believe that I did. Never, ever, ever did I do it because my obligation was to serve them like it was to serve anybody else in Atlanta.”

Vision for the Future.

“Maynard H. Jackson for Senate” advertisement. June 23, 1968, Atlanta Journal via Newspapers.com

When reflecting back on white business resistance to Black leadership in Atlanta, 1988.

“I hope that as we look back in time, we’re not going to be caught up in hatred and caught up in vitriolic retribution. And even as low-down as some things were that happened, the future belongs to those who are going to be able to put it behind us and to say, ‘I may not like what you did, you may not like what I did, but each of us was groping for the right way to deal with each other.’ And I think that Atlanta today, relative for all of our problems, historically, still, compared to every other major city in this country, is ahead, without question.”

Future of Atlanta Public Schools, 1988.

“We’re 92%. Now, what does that say? What it does say is there’s been a tremendous disinvestment by many whites and by a substantial number of middle- and upper-income Blacks in the Atlanta public school system. Now, our schools are better than they used to be, but I’ll tell you this, if all of a sudden, the Atlanta school system becomes one of the top two, three, four school systems in the nation in excellence of education, there’ll be a massive return of people who don’t want to pay taxes for public schools and pay money to private school, also. Mark my word.”

C-Span Interview on what the future of Democratic party needs to be, 2001.

“The Olympics in a two-thirds colored world never would have come to Georgia, to Atlanta specifically, if we’d not been able to show that we have a history in Atlanta of acting inclusively. Not perfect race relations, but we’re always in pursuit of perfect race relations. Many cities don’t try. We work at it constantly, and so inclusion is going to mean that we’re going to find a way to organize to be sure that everybody is under the same tent and on the same agenda.

Influences and Inspirations.

Mayor Maynard Jackson conducts business at Atlanta City Hall, 1975. Boyd Lewis, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

On how his family influenced his beliefs on integration, 1988.

I’m an integrationist, philosophically. I was trained that way. And I had a family that believed in and worked for it. Integration is not the usual. If it were, you wouldn’t have to pursue it; it would just be there, right? So, my parents and grandparents have worked at it for years in terms of personal relationships and the broad societal compact, politics, economics, the whole thing. It’s been a way of life in our family. I feel the same way.”

Family policy on segregation, 1988.

“When I was growing up as a boy in Atlanta from the age of 7—we moved here from Dallas, Texas, where I was born, but Atlanta’s my mother’s native home—it was hardcore segregation, all the way. But we never bowed to it; it was against the family policy. We never walked in anybody’s back door, ever. And I even dated a young lady one time who wanted to go to a movie at the Fox Theatre, which at that time had a buzzard’s roost, as we called it. So, Black people were expected to go around the side of this theatre, and walk up all these steps. So, back in the ’50s, she wanted to go and see this movie. I asked where was it playing, and she said it was playing in the Fox Theatre. I said, ‘I’m sorry, but we don’t go to the Fox Theatre.’ So, we talked about it, she, Well, this is the only movie I really want to see tonight. I said, ‘But do you understand my policy?’ She said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Well, I want to try to accommodate you, but I can’t go.’ She said, ‘Well, I don’t really understand that. ‘I said, ‘Fine, let’s go.’ So, I took her to the theatre. I bought one ticket, gave it to her, and told her I’d come back and pick her up when the movie was over. So, she got a little upset, but she went on and saw the movie, came out, I was there waiting. I took her home and never called her again. I’ve walked into shoe stores with my father and my grandfather to be fitted for shoes. We would sit down, and then they would ask us to move to the back of the shoe store. And we’d explain, if we’re going to spend our money, we’d sit anywhere we wanted to. They said, ‘Well, you gotta go to the back.’ We said, ‘I’m sorry, no, we don’t have to go to the back.’ If our choice was to go to the back or leave, we’re leaving.

Words of Wisdom

Speaking at his youth foundation, 1996.

“Nobody is going to come riding down Peachtree Street in a chariot with a sword in hand to tap us on the shoulder and free us. We must do everything we can for ourselves.”