Map of Cuba, showing the Bay of Pigs. Zleitzen, Wikimedia Commons

“We were taken to Havana on buses,” said Albert Bolet. “The people in the towns would come out and bang on the side of the buses, and they would yell, ‘Paredón! Paredón!’ That means ‘to the wall!’ So, they wanted the government to execute us, and I told my brother, ‘That’s what they do with political prisoners, so better get ready for that because that’s going to happen to us.'”

In January 1959, Albert was just 17 when his parents sent him and his younger brother to Miami to escape the increasingly repressive policies of Fidel Castro’s government in Cuba. His parents knew young people who disappeared or were jailed for protesting the Batista regime, and when Castro came to power, the same things were happening to those who opposed his policies.

When his parents’ home and business were seized during Castro’s “Reforma Urbana,” the rest of Albert’s immediate family fled Cuba for Miami as well, joining the largest refugee flow in U.S. history.

Almost 60 years later, in his September 21, 2020, Atlanta History Center’s Veterans History Project interview, Albert remembered graduating high school in Miami and being admitted to the University of Miami’s school of civil engineering. He attended on a scholarship provided to political refugees from Cuba. There, he joined the Air Force ROTC program, and it seemed that life in his adopted country had stabilized somewhat.

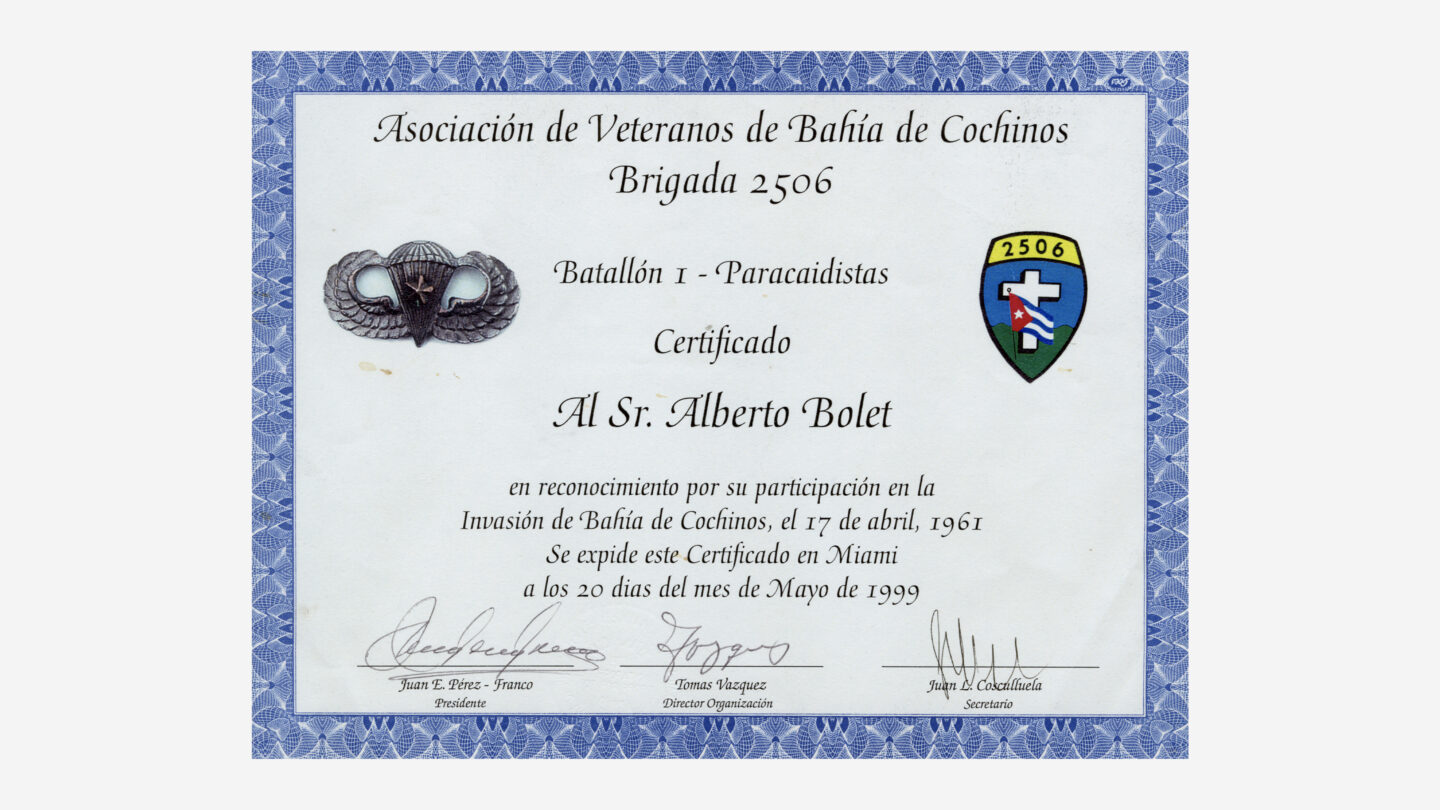

Albert Bolet shares his experiences as a Cuban refugee serving in the Bay of Pigs invasion. He discusses his family, the history of Cuba and the Cuban government, and the Cuban revolution. Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

But one night, his younger brother, Armando, announced that he and two friends had volunteered to join a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA)-backed military unit that intended to liberate Cuba.

“He came home one day, and he said, ‘We’re going to go and fight with the American army and overthrow Fidel Castro,’ and I said, ‘Wait a minute! What are you talking about?’ I was perfectly happy doing what I was doing. My brother and I had very close ties, so I said, ‘OK, I’ll go with you.’ I loved my country, I didn’t like Fidel Castro, I had many other reasons to do it, but the primary reason, practically when you come down to it, was to protect my brother and make sure that he made it through that. I wasn’t going to let him go by himself.”

The brothers left home without telling their parents. They met in a nearby Miami neighborhood with members of the Frente Revolucionario Democrático, known as “El Frente,” an anti-Castro, anti-communist, and anti-Batista group. They were asked questions about their backgrounds and political beliefs and met the group’s recruiting criteria, for they soon found themselves on an unmarked C-54 aircraft on their way to Guatemala.

The cover of Dark Nights in the Castle of the Prince, Albert Bolet’s memoir.

Albert donated a copy of his memoir, Dark Nights in the Castle of the Prince, to Atlanta History Center following his interview. In it, he describes his training in Guatemala and recalls that his paratroop instructor was a U.S. Army veteran of the Normandy invasion during World War II. The instructor had also been an adviser to French troops in Vietnam. Albert described his combat experiences in detail, including capturing San Blas, running out of ammunition on the third day, and retreating to the beach where his unit was ordered to the Escambray Mountains in hopes of joining guerrilla forces there.

He reflected on the invasion, including the many tactical and strategic errors that led to its failure, principally the lack of promised U.S. air support.

Albert and Armando were captured and spent 20 months in captivity, 18 of them in the Castillo del Principe, a fortress well known for housing political prisoners since 1767. They were fed with whatever surplus food happened to be available.

He remembered eating pumpkin every day for weeks. He recalled heightened tensions among his captors in Fall 1962. He had no idea that the United States and the Soviet Union were on the brink of war in what would become known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, but he remembered Castro’s troops drilling holes in the prison walls near the ceiling.

When the prisoners asked the troops what they were doing, they were told, “Si vienen los yankees, ustedes son los primeros que se mueren,” which means, “If the Yankees come, you will be the first to die.” The guards filled the holes with explosives.

In December 1962, the prisoners were released and returned to Miami in exchange for $53 million in baby food and medicine in a deal brokered by well-known diplomatic negotiator James Donovan.

When asked how he feels about the United States’ handling of the invasion, Albert said,

“Because of this failure to depose this person when we had an opportunity to do so, the people of Cuba have been subjected to poverty, to horrendous lack of freedoms and human rights, and just economic devastation. They continue to risk their lives to ride rafts to the United States. They continue to do that. So, it was an opportunity lost. My primary feeling is one of sadness that that opportunity was lost.”

Albert and Margarita Bolet. Gift of Albert J. Bolet, 2020, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Albert and his wife, Margarita, settled in Atlanta in 1970, and he reflected on his life here, including meeting two individuals who fought with Castro’s forces opposing the invasion in 1961.

“These people were my enemies,” he recalled. “They were there to kill me. It turned out that 20 years, 30 years later, they were my best friends.”

Albert’s love for Cuba and for his adopted country is palpable. He became a United States citizen in 1967. He concluded his interview saying, “I am an American. I am an American citizen. This is an American flag,” pointing to an American flag emblem above his left-hand coat pocket, “I wear this all the time. There is an American flag that flies in front of my house every day.”

Atlanta History Center’s Veterans History Project collects, preserves, and shares oral histories of American veterans who served in World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Persian Gulf War, the Global War on Terror, and civilians who supported them. These personal stories enable future generations to hear directly from veterans and gain a deeper appreciation of the realities of war and the sacrifices made by those who serve in uniform.

The interviews are created in partnership with the Veterans History Project, an initiative of the Library of Congress American Folklife Center. AHC is a founding partner and has collected more than 800 interviews with veterans, with the invaluable assistance of the Atlanta Vietnam Veterans Business Association and the Atlanta branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

To participate, contact Sue VerHoef, Atlanta History Center’s director of oral history and genealogy, at (404)814-4042 or sverhoef@atlantahistorycenter.com.