The Fulton Bag and Cotton Company and the Labor Movement in Atlanta

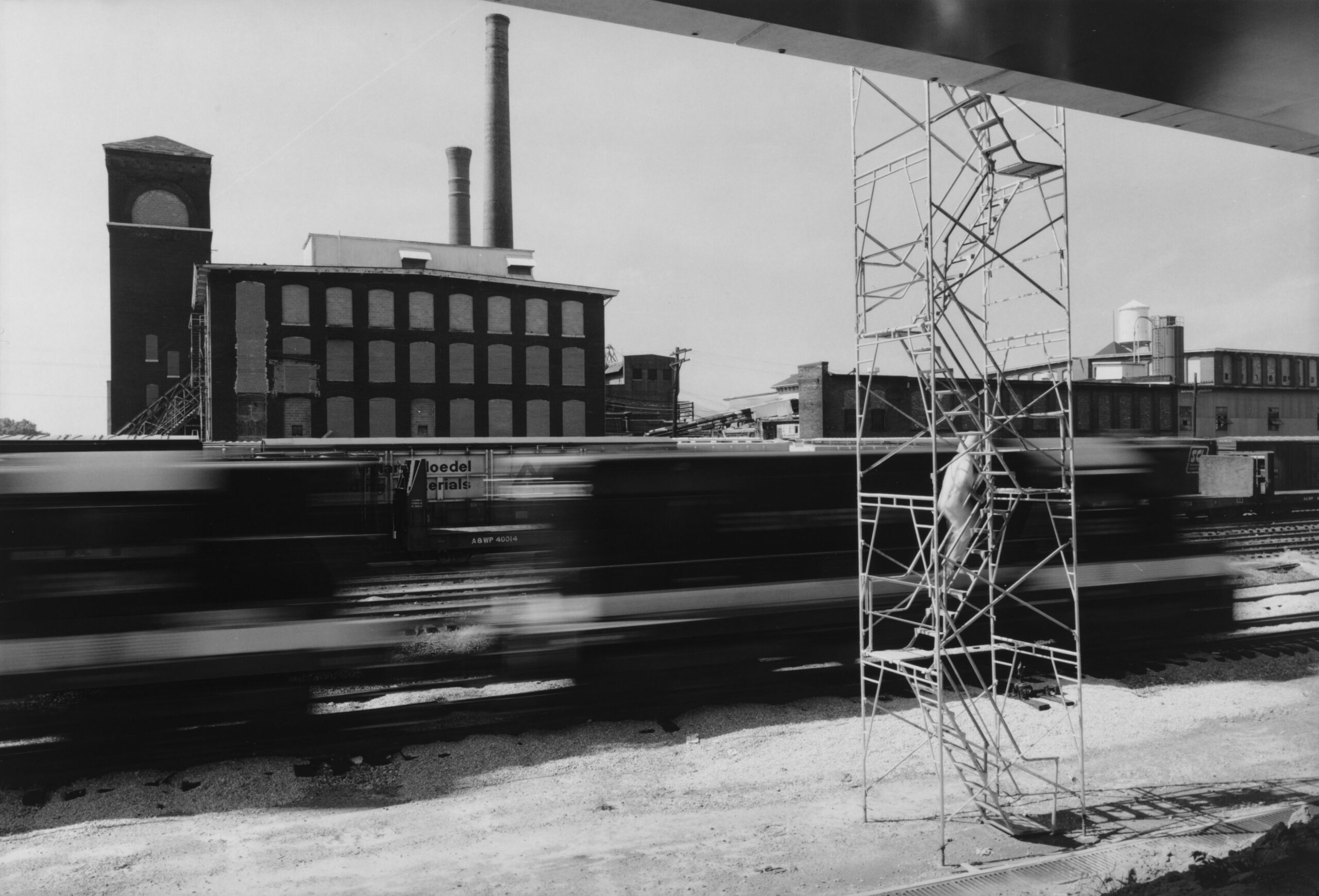

View of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill and trains as seen from the construction of MARTA’s East Line circa 1977 (VIS 115.17.01, Martin Stupich, Martin Stupich Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Depending on who you are and your station in life, the view from a MARTA train can be thrilling or tiresome. While zooming through the city on MARTA, you get snapshots of city life and architecture. One of the buildings that you may pass while riding on the east-west line towards King Memorial Station is the old Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills. The large, reddish brick building framed by smokestacks looks impressive. Like it has a story to tell. And it does. One of the biggest revolves around the labor movement in the South.

Long before workers at multinational companies such as Starbucks and Amazon began fighting to collectively bargain with their employers to address income inequality and improve working conditions, workers at Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills fought to unionize, creating a blueprint for those who would dare to belong to a union in the present-day.

How it Started

Today many of the buildings that made up Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills have been transformed into lofts, boasting “fabulous amenities” and a “great location.” In the mill’s heyday, however, it was Atlanta’s top cotton cloth and paper bags producer. Bags produced at the mill were primarily used for packaging agricultural products. At one time, the mills were the largest employer in Atlanta and had subsidiaries in other cities such as New Orleans, Dallas, and St. Louis.

Jacob Elsas was the visionary behind the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills. He was an industrial capitalist whose notable contributions to Atlanta, besides the mills, include large donations that helped establish Georgia Institute of Technology, Grady Hospital, and Hebrew Orphan’s Home.

Elsas’ story is very much one of rags to riches. He was a Jewish German who immigrated to the United States just before the Civil War. After a stint selling goods in Ohio, he relocated to Cartersville, where he opened a dry goods store. After noticing that bags for agricultural goods such as salt, flour, and sugar were scarce in Atlanta, Elsas moved there and started a mill with Isaac May. When Elsas bought out May, he established Fulton Cotton Spinning Company, which became Fulton Bag and Cotton Company.

Aerial view of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill in the Cabbagetown area of Atlanta. (VIS 170.102.001, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Fulton Bag and Cotton Company began operations in 1881, shortly after the International Cotton Exposition, on the site of the Atlanta Rolling Mill, which had been destroyed during the Civil War.

Elsas started the company at a time when technological advances made the creation of textiles less of a skilled, artisanal trade and more of an industrial, streamlined endeavor that was less labor-intensive, faster, and more profitable.

Factory Life

Fulton Bag and Cotton Company recruited poor whites primarily from Appalachia to work the machines in its integrated mill, where cotton was separated, straightened, and turned into yarn and cloth that was used to create bags and other goods.

Before working at Fulton Bag and Cotton Company, many of these whites eked out livings as subsistence farmers. When word reached their small towns that textile mills such as Elsas’ had plentiful work, workers willingly traded hoe and spade for “public” or factory work because it paid more.

Forrest Lacock, who went to work at Carrboro Mill in Carrboro, N.C. said, “The trouble with what we call one-horse farming, you can’t have an income sufficient to take care of all your bills. A public job is more interesting because you can meet your bills.”

Others joined the workforce at Southern textile mills because they saw the 60–70-hour factory workweek as less physically demanding.

Dewey Helms, the son of a textile factory worker, recalled that his father “wasn’t worried about the income he made on the farm; he made as much as he cared about. He wanted to get rid of the harder work. Working in the cotton mill was not as hard work as running one of them mountain farms.”

Whether they went to work at Fulton Bag and Cotton Company for financial stability or ease, the newly minted mill workers still had to get used to the differences between factory work and farm life.

Millhands lived in shotgun houses in Fulton Mill Village (now known as Cabbagetown). The village, also known as Factory Town, was infamous for the impoverished quality of life it offered its residents. Instead of amenities, millworkers and their families lived with minimal sanitation, overcrowding, and outbreaks of diseases.

Cabbagetown home circa 1910 –1920. (Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills Digital Collection, Georgia Institute of Technology)

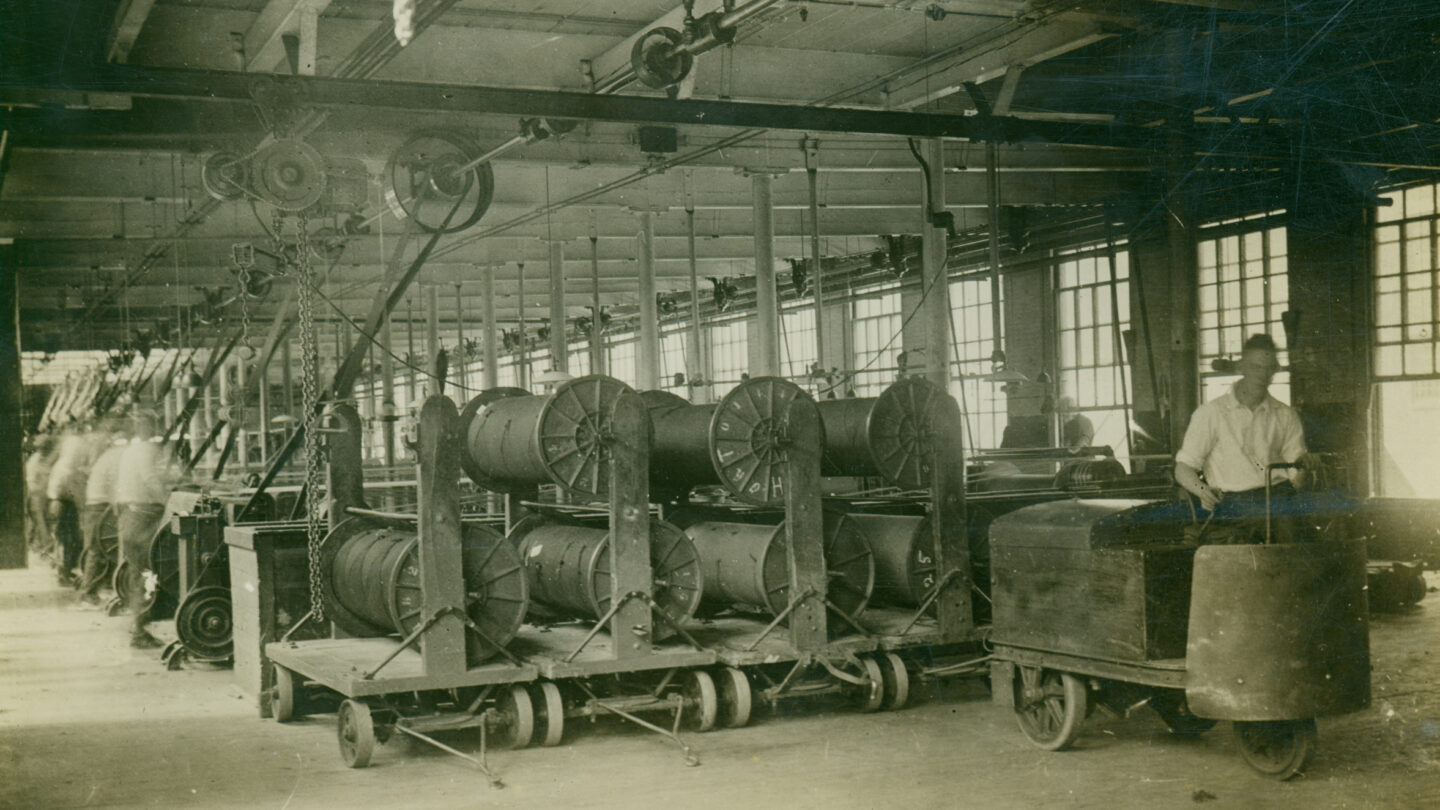

Millworkers labored from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. in Elsas’ mill for meager wages. A 1915 report said the average worker could earn up to $20 a week (about $500 a week in 2022). Family units who worked at the mill could earn a little bit more at up to $65 a week. Every morning, they would stroll down the village’s narrow streets and shuffle to the factory where they toiled at their machines, pulling, stretching, spinning, weaving, and finishing cotton in intense heat and noise. Overseers not only ensured that work was done efficiently and to the company’s standards, but they also reported unproductive workers to higher-level managers so that they could be fined or fired.

Men work inside the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills circa 1910–1930 (Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills Digital Collection, Georgia Institute of Technology)

Chester Copeland, a millworker from North Carolina, called the long, 12-hour shifts that were common at most Southern mills “a robot life.”

“Roboting is my word for it,” he said. “In the mill you do the same thing over and over again-just like on a treadmill. There’s no challenge to it-just drudgery.”

In addition to being monotonous, it was also dangerous work. Mills were filled with cotton dust that not only caused breathing and lung problems that millworker Carl Durham said “killed some folks,” but the machines also sometimes left workers with mangled hands, arms, and bald scalps.

Millworker Alice Evitt said of the speeder frames, “I know one lady-I didn’t see her get it done-but she said she wore wigs [because] she’d got her hair caught and it pulled her whole scalp out-every bit of her hair. Them speeders was bad to catch you.”

When accidents did occur, there was little relief for those who suffered. “Back before now,” Mack Duncan recalled, “if you got hurt on the job, you just was hurt. If you couldn’t work, you had to go home; you lost your pay.”

One-sided employment contracts provided workers with little recourse when injured on the job. These contracts placed all injury liability on the worker and prevented them from seeking financial relief from Fulton Bag Company. Workers could also be fined for damage to equipment.

Despite the tedium, danger, and deplorable labor conditions, for the most part, workers at the Fulton Cotton and Bag Company tried to be content with their situation. After all, Jacob Elsas did offer his workforce benefits uncommon at the time such as a cafeteria, medical and dental care, a library, and nursery services. Consequently, Fulton Cotton Mills employees did not attempt to unionize until August 3, 1897, when Elsas hired 20 Black women to work in the mill’s folding department.

Two Small Strikes

In the folding department, women sorted and folded bags. It was typically seen as work suitable for white women only. Until Elsas’ hiring of the 20 Black female workers, black workers performed the most basic tasks for rock-bottom wages. Black men and women were excluded from production jobs such as spinning and weaving—jobs that had been a Black domain during slavery. They were the laborers who moved bales of cotton and loaded vehicles with finished textiles. They were the truck drivers. They were the people who swept and scoured the floor. They were the people who performed the most menial jobs. They worked in the picker rooms, where they unpacked the cotton from bales and removed such debris as twigs, leaves, and bugs, or the dye house where they dyed and dried cotton. Elsas’ factory was unusual in its hiring of African Americans. Nationally, until 1965, less than 2% of textile workers were Black.

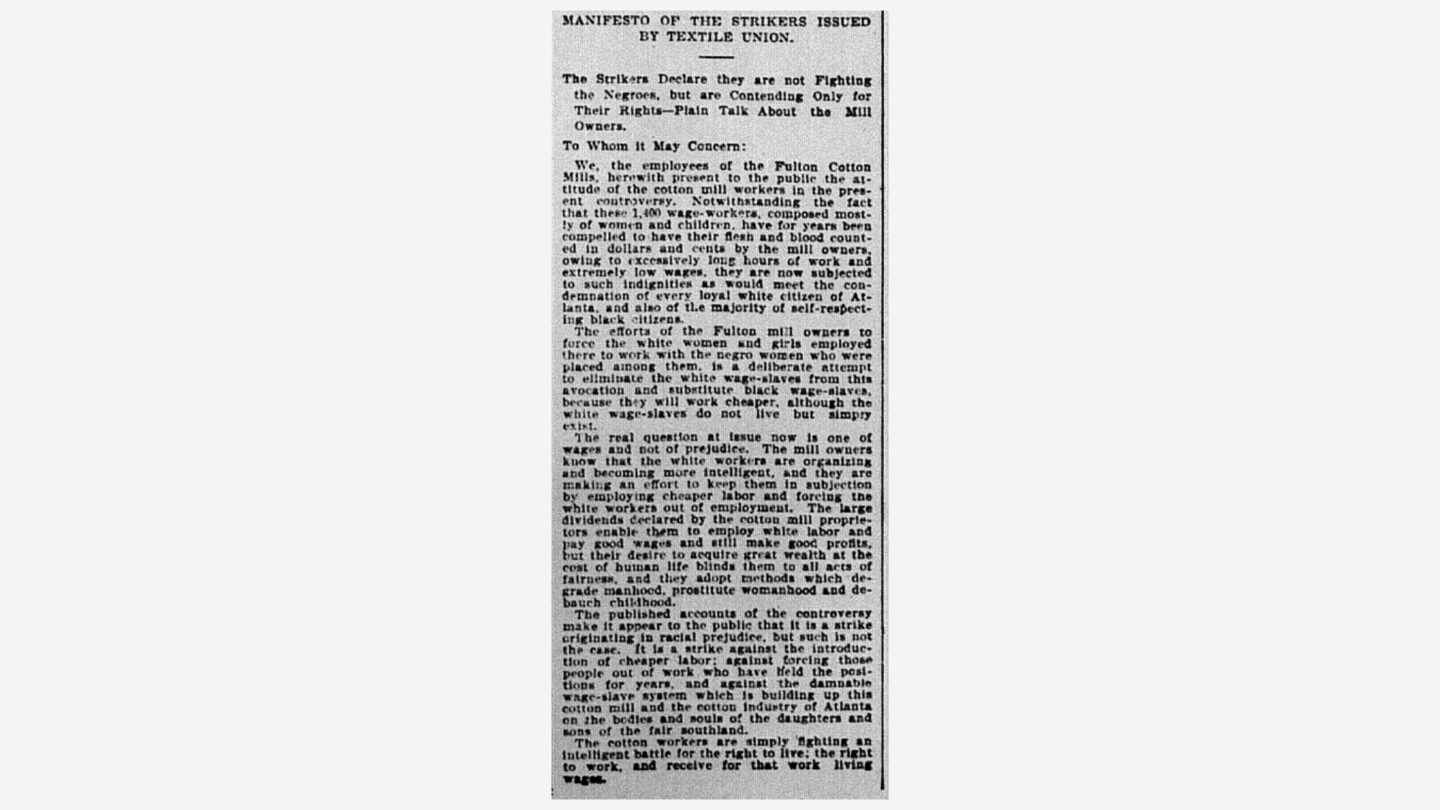

The Black women Elsas hired weren’t replacing white women. They were even required to perform their duties in an area separate from white workers. Nonetheless, white folders walked off the job in protest on August 4. They were joined by many other mill workers, leading to a shutdown of the mill. As the labor movement in the U.S. began to take shape, many workers at the mill also decided to unionize, joining the Textile Workers’ Union.

Excerpt from Executive Committee, Textile Workers’ Union, “Manifesto of the Strikers,” Fulton Cotton Mill, Atlanta, Georgia, 1898, in The People (New York), 6 August 1899.

With the crowd of 1,400 mill workers demanding that Elsas fire the newly hired Black women and all the Black people who worked at the mill, police were called in to keep the peace. Elsas agreed to negotiate with the strikers in the face of deteriorating conditions. Hoke Smith, a former secretary of the interior, was brought in to arbitrate. On August 5, 1897, Elsas agreed to fire the new Black hires but refused to fire his entire Black workforce. The mill resumed hiring Black women by 1900, and by 1914, they made up 11% of the factory’s workforce. Just four years later, in 1918, the mill was the largest employer of Black women in Atlanta.

While Elsas did not immediately fire those who participated in the strike, he did fire some of its leaders a few months later. Elsas’ action triggered another strike as workers believed he had violated the terms of the August strike settlement by firing the strike leaders. On December 7, 1897, most of the company’s 1,200 workers went on strike. They wanted Elsas to rehire the fired strike leaders and provide assurance that Elsas would not lower their wages or replace them wholesale with Black laborers. Elsas refused to rehire the fired strike leaders and performed a lockout, shutting down the factory temporarily and denying the striking workers access to the mill. He then began evicting those striking from their dwellings in Cabbagetown. Strikebreakers joined non-striking workers when Elsas reopened the mill. The strike lasted until January and ended with many strikers losing their jobs. Though workers at the mill remained in favor of organized labor, the union at the mill fell apart a year later in 1898 after an attempted strike by the mill’s weavers. This strike stopped before it could get started because the rest of the unionized mill workers did not support it.

And a Big One

On October 23, 1913, more than 300 loom fixers and weavers performed a work stoppage in protest against the firing of a loom fixer and a new company policy that extended the time needed to give notice of resignation from five days to six days. The work stoppage lasted for less than a week and led the company to alter its policy on giving notice. It did not, however, lead to the fired workers being rehired.

The stoppage caught the attention of the United Textile Workers of America (UTW), a national textile union affiliated with the larger American Federation of Labor (AFL), that was trying to increase its footprint in the South. The union organized a membership drive at the mills. It was a success with hundreds of mill workers joining the UTW. On October 31, 1913, the mill became home to UTW Local 886. The Fulton Bag and Cotton Company did not formally recognize the union or employ union-busting tactics to break up the union. Still, the company did hire undercover investigators to track union activities.

After becoming UTW Local 886, one of the first action items union members wanted to resolve was the Fulton Bag and Cotton Company’s wrongful firing of more than 100 union members from October 1913 to May 1914. Before resorting to a possible strike, local UTW leader Charles Miles attempted to discuss this grievance with Oscar Elsas. Oscar Elsas, who had become mill president after his father, Jacob, retired at age 70 in 1914, rebuffed the complaint and bragged to Miles that he had actually fired more than 300 workers during the contested timeframe.

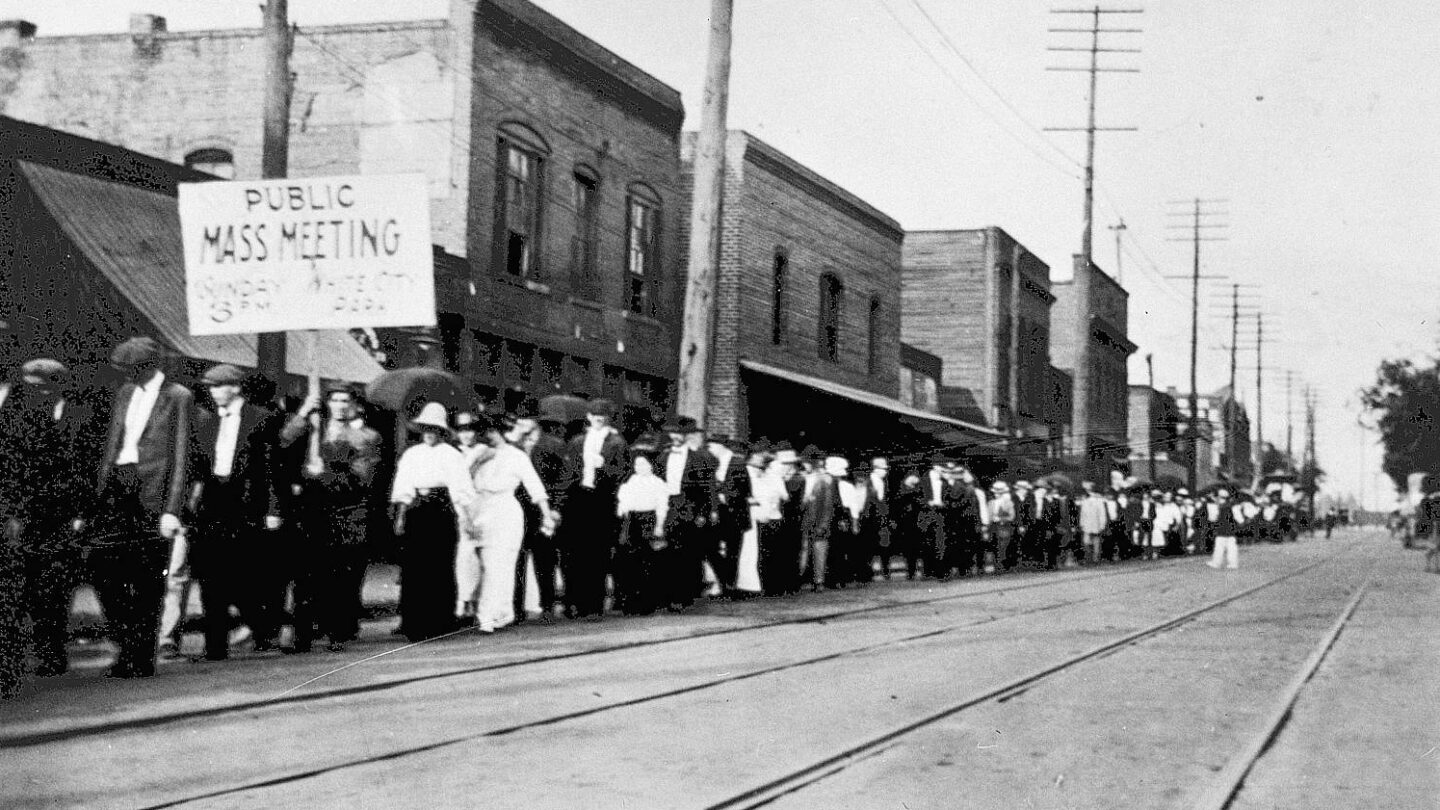

Faced with Elsas’ opposition to negotiation, union members voted to go on strike. On the morning of May 20, 1914, loom fixers and weavers in the union walked out. They set up picket lines in various locations in Atlanta, including railway stations and the underpass on Boulevard that is an entryway to the mills.

Strikers walking down Decatur Street. Sign reads: “PUBLIC MASS MEETING SUNDAY 3PM WHITE CITY PARK.” (L1983-38_06, Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill Strike Photographs, Southern Labor Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.)

Strikers hoped that their absence would cause a work stoppage and shut down operations. They also hoped the strike would force Elsas to end the fines and deductions stipulated in the company’s employment contract, institute better working conditions, establish a shorter workday, and offer workers increased pay. The striking workers also demanded an end to child labor at the mills. There were approximately 1,300 people employed at the mills, 12 percent of whom were children under 16, at the time of the strike.

Milton Nunley, former child worker at Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill (L1985-34_006, Labor Photographs, Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill, Strike of 1914-1915 collection, L1985-34, Southern Labor Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.)

Miles, Sara Agnes Mclaughlin Conboy, Mary Kelleher, Ola Delight Smith, and H. Newborn Mullinax, led the strike. The UTW and the Atlanta Federation of Trades (AFT), Atlanta’s organization of local unions, began a campaign to raise funds to support striking workers, with the UTW adding $500 per week to the strike fund and the AFT levying a $0.15 weekly tax on its members. The groups also raised money from those sympathetic to the strikers’ plight.

Though Elsas publicly refused to acknowledge the strike, calling it a “little disturbance,” he leased skilled workers from other mills in the area so that Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills was operating at pre-strike production levels. Elsas also ordered the eviction of the striking workers and their families who lived in the mill village.

Eva Steven’s family with furniture in the street. Sign reads: “PUT OUT BY MILL OWNER.” (L1983-38_20, Fulton Bag & Cotton Mill Strike Photographs, Southern Labor Archives, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.)

These evictions were photographed and used as propaganda to engender public sympathy. Some of the men hired to evict striking families were Black. The UTW used images of the Black men evicting the strikers to evoke feelings of white racial solidarity thereby garnering support from whites. Additionally, strikers created and exhibited movies showcasing their living and working conditions. The UTW rented a boarding house to house the evicted workers. It also provided free food for strikers via a commissary it established.

Organizations such as Men and Religion Forward Movement, a progressive Christian organization that was affiliated with many of Atlanta’s Protestant churches, rallied around the strikers. The group criticized Fulton Bag and Cotton Company for the unsanitary living and poor working conditions to which it subjected its employees. On July 7, the Men and Religion Forward Movement petitioned the Commission on Industrial Relations to send representatives to Atlanta.

When a team from the commission arrived in Atlanta to investigate the strike, they spent a week gathering extensive research and testimony at the mill. They met with Oscar Elsas on July 16 and 21. The commissioners urged him to submit to arbitration in both meetings, but Elsas refused. Elsas maintained that the mills were fully functional and there was nothing he needed to negotiate with the strikers.

The commissioners later submitted a report to the U.S. Department of Labor that commiserated with the strikers but acknowledged that there was little that they thought the agency could do. Mill owners and local politicians actively worked to block the release of the report and its accompanying testimonies as they did not want to face public backlash or further governmental intrusions into commonly accepted business practices in the South.

During the strike, UTW Local 886 continued to accept new members, many of whom were day laborers who joined the union to access its benefits. By mid-July, the union changed its membership rules to prohibit freeloading. At the time, more than 1,600 people were using the union commissary, costing the union $1,000 a week.

At the end of July 1914, Fulton Bag and Cotton Company announced that it would never rehire those involved with the strike, and by August, with production levels the same as those before the strike, Elsas proclaimed that the strike was over. Additionally, citing financial difficulties and a lack of optimism about the strike’s progress, the AFT pulled its support, leaving the UTW to carry on with the strike alone. With a reduced cash-flow due to the decrease in financial support, the union began housing strikers in a tent city near the mills.

After a change in leadership, the UTW hoped to reinvigorate the strike effort by carrying out reforms such as banning alcohol in the tent city, covertly sending union agents into the mills to recruit more strikers, and evicting non-strikers. By December 1914, only 35 original strikers remained of the 200 people who lived in the tent city.

Textile workers gather at the mess tent during the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill strike. (L1985-34_111, Labor Photographs, Fulton Bag and Cotton Mill, Strike of 1914-1915 collection, L1985-34, Southern Labor Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University, Atlanta.)

Despite the actions taken by the UTW, the next several months saw no real progress in winning the strike. A failure to recruit additional strikers from the mill in addition to a labor surplus and an inability to organize the nearby Exposition Cotton Mills, led to many seeing the strike as a hopeless situation.

On May 15, 1915, 360 days (about 12 months) after it began, the strike ended. The tent city was dismantled, the commissary shuttered, and the union arranged for the remaining strikers to return to their homes or to their new places of employment.

Though the 1914–1915 Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills strike was not successful in the end, it led to greater national scrutiny of working conditions at southern textile mills and several of the recommendations made by the U.S. Commission on Industrial Relations were put into law in the years following the investigation. It also laid a blueprint that later strikes in the South would follow, such as the 1929 Loray Mill strike and the 1934 Textile worker’s strike.