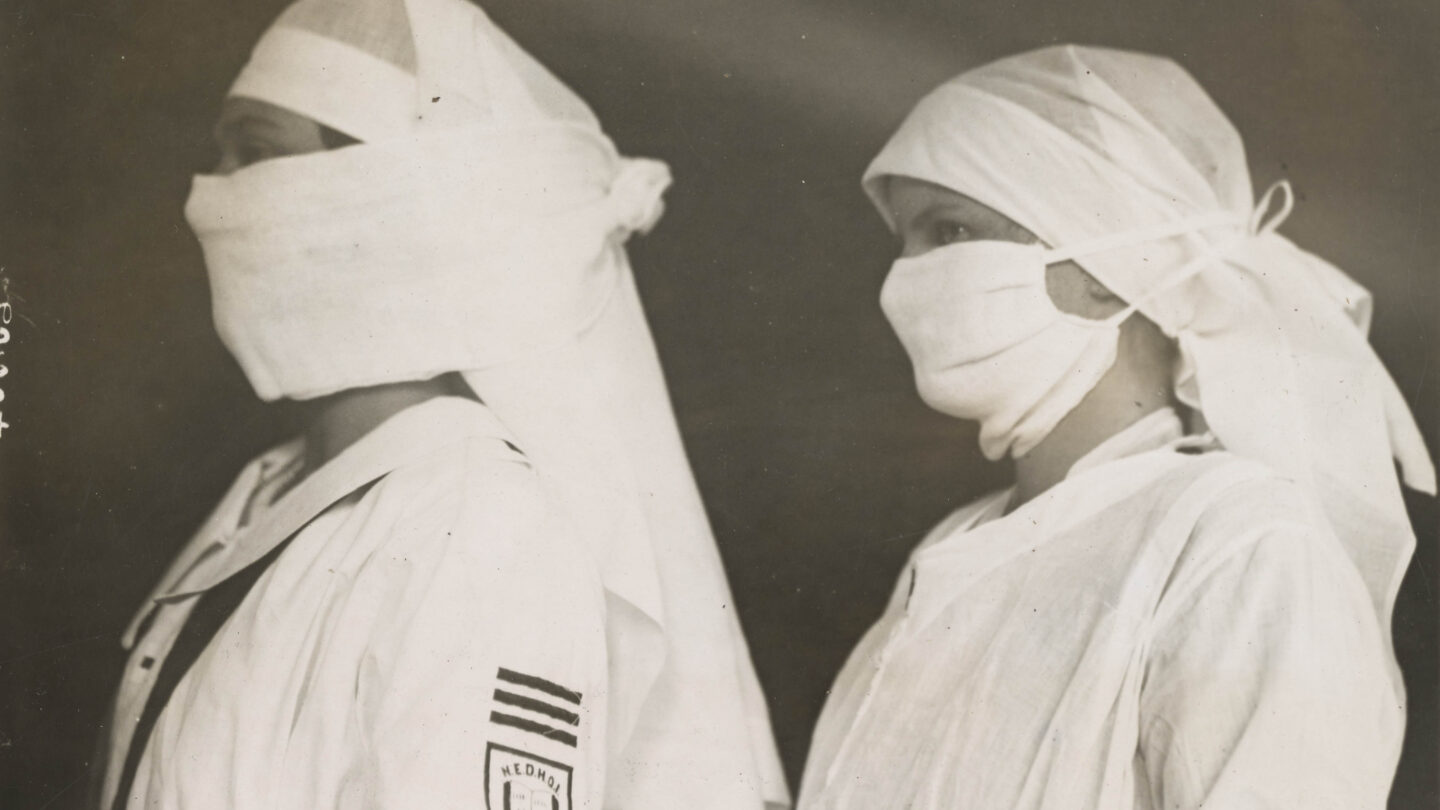

Nurses wearing handmade masks during the 1918 pandemic. | U.S. National Archives

In times of uncertainty, humans look to the past for guidance. It’s no surprise in a new era of public health that we’re digging through our medical history as a species, looking for answers and solace in previous pandemics. Since March 2020, Google searches for “Spanish Flu” and “1918 flu” have reached their all-time peak in the United States. Rising searches—queries with the biggest increase in search frequency during a specified time period, in this case March 2020—include “coronavirus vs Spanish flu,” “how long did Spanish flu last,” “1918 flu pandemic,” “1918 flu deaths,” and “Spanish flu 1918 death rate.”

What sort of results do those searches get? The long and short of it is that the 1918 Influenza was the most severe pandemic in modern history. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—headquartered right here in Atlanta—at least 675,000 Americans contracted the virus. One third of the global population was infected and an estimated 50 million people died.

You could call the 1918 flu living history. According to Drs. Jeffrey K. Taubenberger and David M. Morens, all Influenza A pandemics since 1918 (with a small number of exceptions) have been caused by descendants of the deadly 1918 virus. That includes the H1N1 virus responsible for the 2009 global flu pandemic. For this reason, the 1918 virus is known as “the mother of all pandemics.”

This desire to understand our shared past in order to build a better future is the cornerstone on which institutions like Atlanta History Center are built. To answer these common questions and to better prepare our community for the days ahead, we’re examining the impact of the 1918 pandemic on our city.

The Infirmary at Camp Gordon during its completion in 1917. | U.S. National Archives

Origins of the 1918 Virus in Atlanta

In 1918, with the world near the end of the WWI, American military training camps were churning out soldiers as fast as they could. With the high volume of humans in close and constant contact, diseases spread rapidly throughout the barracks. Unsurprisingly, the first documented cases of Spanish Flu in Georgia occurred just a few miles north of Atlanta at Camp Gordon in Chamblee, Georgia.

Under orders from the camp commandant on September 18, 1918, camp officials began isolating soldiers if they showed symptoms of the flu. Two days later, over half the camp was put under quarantine. On September 27, the Atlanta Constitution noted that even though it wasn’t confirmed as Spanish Flu, it looked and acted like Spanish flu, so it was almost certainly Spanish Flu.

Call to action in the Atlanta Constitution requesting gauze masks be sent to Camp Gordon.

When one soldier became sick, his entire unit was put into quarantine. Two days later there were 1,893 reported Spanish Flu cases at Camp Gordon. Of those cases, 962 patients were hospitalized and 120 contracted Pneumonia.

Chief Surgeon Frank T. Woodbury seated at his desk at Camp Gordon ca.1919. | US National Library of Medicine

Chief surgeon Colonel Frank T. Woodbury handled the Camp Gordon outbreak. To limit the spread of disease, he ordered soldiers to wear gauze masks, sleep outside 50 feet apart, and gargle and nasal rinse several times a day. In addition, visitors were firmly restricted, an antiseptic oil was applied to roads, and for two weeks soldiers could not congregate in the hall or amusement areas. Soldiers were further quarantined if they spiked a fever.

To help the sick, the camp requested additional nurses from the Red Cross and the Atlanta Registered Nurses’ Club in late September and early October. Like today, medical professionals pushed their limits to care for the sick in an effort that was nothing short of heroic.

Nurses in front of the infirmary at Camp Gordon in 1918. | U.S. National Archives

On October 17, the Constitution reported that Camp Gordon would undergo a “greatly modified” quarantine. The modification lifted the need for regular gargles and nasal rinses, except for new recruits, who were also required to remain separated for 10 days and to wear a mask. Recreation areas across the camps were reopened, but men were required to wear a mask when in these spaces.

Because of the strict quarantine rules, Camp Gordon suffered a smaller percentage of infections than the City of Atlanta. By November, more units were let out of quarantine. News outlets reported that the total cases number of reported flu patients at Camp Gordon hovered around 6,000. According to the Constitution, 93% of influenza cases did not require hospitalization. There were an additional 627 cases of pneumonia and 166 deaths.

Care and Prevention

As it is today, personal protective equipment was in short supply in 1918. Misconceptions about how germs and disease spread, which lead to some unusual design choices of PPE. Newspapers issued calls for handmade masks to be sent to facilities like Camp Gordon. The Constitution issued a call for 100,000 handmade masks from female readers. A subsequent article gives simple instructions on how to make a “flu mask” at home:

“Masks are made easily at home. A piece of gauze the size of a full letter sheet folded twice; tape or string attached long enough to reach around the head and tie, attached to corners is all there is to it.”

The Red Cross issued calls for new nurses. Emergency calls exhausted doctors across the city. Communication was heavily impacted when Southern Bell switchboard operators began falling ill.

Southern Bell Telephone placed this ad in the Atlanta Constitution encouraging “patriotic co-operation” from customers.

Some newspaper advertisements use aggressive language, certainly as a scare tactic, to persuade consumers to buy their product as a preventative measure or cure for the disease. Whisky was even discussed (and debunked) as a preventative measure or cure. Ad slogans such as “Influenza: more deadly than war” put the pandemic on the same level as the global conflict which had claimed so many American lives already.

Excerpt of an article from the Atlanta Constitution debunking whisky as a treatment for the flu.

On the more reputable end of the spectrum, the Constitution also detailed preventative measures issued by the Board of Public Health and the U.S. Health Service. Dr. William Brady issued short, daily articles on various topics with Q&As at the bottom; they were called “Health Talks.” He was a regular contributor to the paper, and even though he didn’t always talk about the flu, a majority of his 1918 articles center around the epidemic.

Citizens are encouraged to keep their windows open as a way to fight the flu. | U.S. National Archives

Social Distancing + Quarantine in Atlanta

Though the term “social distancing” is new, the concept isn’t. Isolation of healthy people from sick people occurred long before the 1918 flu. Though the average person’s understanding of germ theory was relatively limited, respiratory illnesses were understood as “spittle diseases” that could be transmitted through close contact.

The U.S. Surgeon General advised using caution, but let the burden of responsibility fall to state governments. Atlanta, like many other cities across the globe, temporarily closed schools, theatres, places of worship, and businesses. On October 8, 1918 the Constitution proclaimed, “Public Gathering Places Closed By City Council for Two Months.” Indoor public gatherings were banned, and people were encouraged to minimize contact with everyone who wasn’t immediate family. (Sound familiar?) It was believed that being outdoors—regardless of group size—helped prevent the spread. Though some medical professionals argued against it, outdoor events and festivals were not cancelled.

Article from the Atlanta Constitution with instructions on how to make gauze masks at home.

The 1918 Southeastern Fair, held in Atlanta, was permitted to remain open under the conditions that people practice social distancing. Police patrolled the event to enforce mask usage. The event’s organizers cited sunshine and fresh air as the justification for remaining open.

Other businessowners weren’t happy with the city’s decision to keep outdoor festivals running while their own arts and entertainment venues withered. The Atlanta Theater Managers Association took their protests to the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce on October 15, 1918, demanding stricter limits at the fair’s midway, and fewer restrictions on movie theatres. The Association asserted that even the President of the United States was patronizing theatres—Woodrow Wilson had attended a movie the past weekend which “must have been crowded on account of his presence.”

For the record, Wilson contracted Spanish flu.

Facing pressure from local businesses, Mayor Asa Candler cut short the order for a two-month quarantine, deciding to “reopen” Atlanta after just two weeks. The reported number of cases had started to decline. Like other cities that ended the measures prematurely, the virus swept through the city in a second, far deadlier wave.

The infirmary at Camp Gordon, taken on November 12, 1918. | National Archives

How many deaths occurred in Atlanta as a result of the flu?

According to the Census Bureau, the estimated death toll for the 1918 influenza was 829 Atlantans. There are myriad reasons why we don’t have an exact count of the number of fatalities associated with the pandemic: health officials stopped reporting numbers; paperwork has been lost over time; misdiagnosed and undiagnosed casualties abounded across the state; many believed that it was a resulting case of pneumonia, and not the influenza virus itself that was deadly, skewing the curve. Echoing today’s pandemic, there was no accurate or reliable testing available at the time—scientists weren’t able to correctly identify the Spanish Flu strain until 1933.

Morbidity Report from the Georgia State Board of Health 1918 Annual Report | Georgia Archives

The Georgia State Board of Health 1918 Annual Report details the state’s response and provides a Morbidity Report. 30,768 influenza deaths are reported for the state of Georgia in 1918. Gonorrhea and syphilis are the next two deadliest diseases in that year with 3,658 and 3,347 deaths respectively. Though giving a total number, the report explicitly states that they don’t have reported numbers on “how many succumbed to the disease [influenza] in Georgia, but the death rate has been high.” Pneumonia deaths are listed separately—937 in total—and there’s no way of knowing how many of those cases resulted from the flu.

That fact, like so many stories from the 1918 pandemic, is lost to time

Recording Current History

When future generations look to the past (and our present), what story do you want them to hear? We’re living through history which makes you the primary source.

Historians have a saying—“that which is most common shall be least common.” Meaning the things we see as commonplace or disposable today are the things future generations will wish had been saved. Atlanta History Center is collecting materials that illustrate how people are experiencing and responding to the COVID-19 crisis. That includes journal entries, iPhone photos, Zoom screenshots, emails, and anything else that captures your experience as an Atlantan during the COVID-19 outbreak.

We invite you to learn more about what kinds of items to submit (including physical objects) to help us better tell this story for future generations. Submission guidelines and the official form are available now.

Further. Reading.

- Wednesday Morning Study Club Records, MSS 580

- Sarah Huff papers, MSS 120

- Minutes of the … annual convention Georgia Division United Daughters of the Confederacy

- The City Builder

- Atlanta Metro Chamber of Commerce records

- Living Atlanta oral history recordings

- Veterans history interview of John Talbot Allan

- Veterans history interview of Raymond Gilbert Davis

- 1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics | US Department of Health and Human Services

- 1918 Pandemic | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Camp Gordon Photographs | National Archives Catalog

- Everyone wore masks during the 1918 flu pandemic. They were useless. | Washington Post

- For coronavirus-hit Atlanta, echoes of 1918 Spanish flu pandemic | Atlanta Journal Constitution

- Historian William Mann On How the 1918 Spanish Flu Changed Hollywood Forever & How COVID-19 Might Too | Deadline

- In 1918, the Spanish flu infected the White House. Even President Wilson got sick. | Washington Post

- Influenza Encyclopedia – Atlanta, Georgia | University of Michigan

- Reconstruction of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic Virus | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- “There Wasn’t a Lot of Comforts in Those Days:” African Americans, Public Health, and the 1918 Influenza Epidemic | US National Library