In 1971, John and Betty Sanford were denied a marriage license in Georgia—despite interracial marriage being legal nationwide since Loving v. Virginia (1967). Refusing to accept injustice, they contacted the U.S. Justice Department, triggering federal intervention that forced Georgia to comply with the law. Just 18 days later, they became the state’s first legally married interracial couple, helping to dismantle Georgia’s last active anti-miscegenation policy.

In the late 1960s, Indiana University’s Bloomington campus buzzed with youthful ambition. It was there that Betty Byrom, a focused graduate student from Georgia, met John Sanford, a tall, lanky sociology student from Indiana. Betty, petite, brown-skinned, and poised, served as a resident assistant in an undergraduate dormitory but often sought quieter moments in the graduate residence hall, where John lived.

Their introduction came through Betty’s friend Madeline, who made sure Betty met everyone in the canteen, including John. What started as small talk turned into an hours-long conversation. By the time they looked up, they were the last two in the room.

“We talked and kept talking,” Betty recalled. “It must have been close to midnight. And it was winter, so it was dark.”

John eventually asked, “May I call you?” Betty agreed, but days passed without a call. Then, a week later, the phone rang.

“I’ll never forget that voice,” she said. “Hello, Betty, this is John.”

An Unconventional Courtship

Despite differences in age, race, and background, Betty and John connected over a shared intellectual curiosity. Betty studied guidance and counseling, while John struggled to stay interested in sociology. Their conversations often tackled questions of purpose, growth, and life itself.

“I felt challenged by this lady—someone smart enough to make me think,” John said. “We argued, but nobody ever won. Though she probably won more often — she knew what she needed to be doing.”

Betty Byrom and John Sanford at John Sanford’s family home in Indiana in 1970. Photo courtesy Betty and John Sanford.

Their dates often involved university theater. Betty, unfamiliar with some plays, used CliffsNotes to follow along.

“What I learned, and what felt so real to me, was that music,” Betty said. “‘I am I, Don Quixote, the Lord of La Mancha.’ It stayed with me.”

Their bond remained strong through a summer apart, when Betty worked for the Upward Bound program in Chicago. John visited often. They explored the city, shared meals, and talked deep into the night. Their love grew in simple, meaningful moments.

Love in a Divided America

As their relationship deepened, so did awareness of the social resistance they might face. John’s parents were accepting but warned of future difficulties. Betty’s parents, too, expressed concern — not out of opposition, but out of love.

“My parents wanted me to be sure,” Betty said. “They could foresee hardship. But we assured them we were committed. And so, they gave us their blessings.”

When Betty met John’s mother, her nerves melted away. “She walked over to my side of the car and greeted me. That was a very welcoming, wonderful feeling.”

A Fight for Justice

In 1971, at ages 25 and 32, John and Betty decided to marry. But when they tried to apply for a marriage license in Georgia, they were denied. Despite the Supreme Court’s Loving v. Virginia decision four years earlier, Georgia’s anti-miscegenation laws were still enforced.

“We didn’t even know such a law was still on the books,” Betty said.

They refused to hire a lawyer. “Georgia was in error, not us,” she said. “I knew without a doubt— I was not going to spend one penny to correct this.”

Instead, they turned to the U.S. Justice Department. Federal attorneys were dispatched to Atlanta, but legal intervention didn’t come fast enough.

On May 8, 1971, with no license in hand, the couple wed anyway. Betty’s brother-in-law, Rev. Ernest Bradford — a minister with civil rights roots — officiated their ceremony at Danforth Chapel at Morehouse College.

Betty Byrom and her father at Betty’s wedding at Danforth Chapel at Morehouse in Atlanta in 1971. Photo courtesy Betty and John Sanford.

“It was a beautiful spring day,” Betty said. “And the photographs show what we felt.”

“She was beautiful,” John added simply.

A friend from Morris Brown College sang Bridge Over Troubled Water. Betty’s best friend stood as maid of honor. Surrounded by love, they celebrated their union despite legal denial.

Weeks later, the state issued their marriage license — backdated to May 8, as Betty had insisted.

“Married on May 8,” John confirmed. “But the license came later — maybe the 23rd or 26th.”

Building a Life Together

After the wedding, the couple joined the structured environment of the U.S. military.

“We didn’t experience much discrimination,” Betty said. “We attribute that to entering the military community, where interracial marriages were more common.”

They moved frequently — Fort Hood, Seoul, Germany — creating home wherever they landed. Their first son, Jawara, was born in 1972.

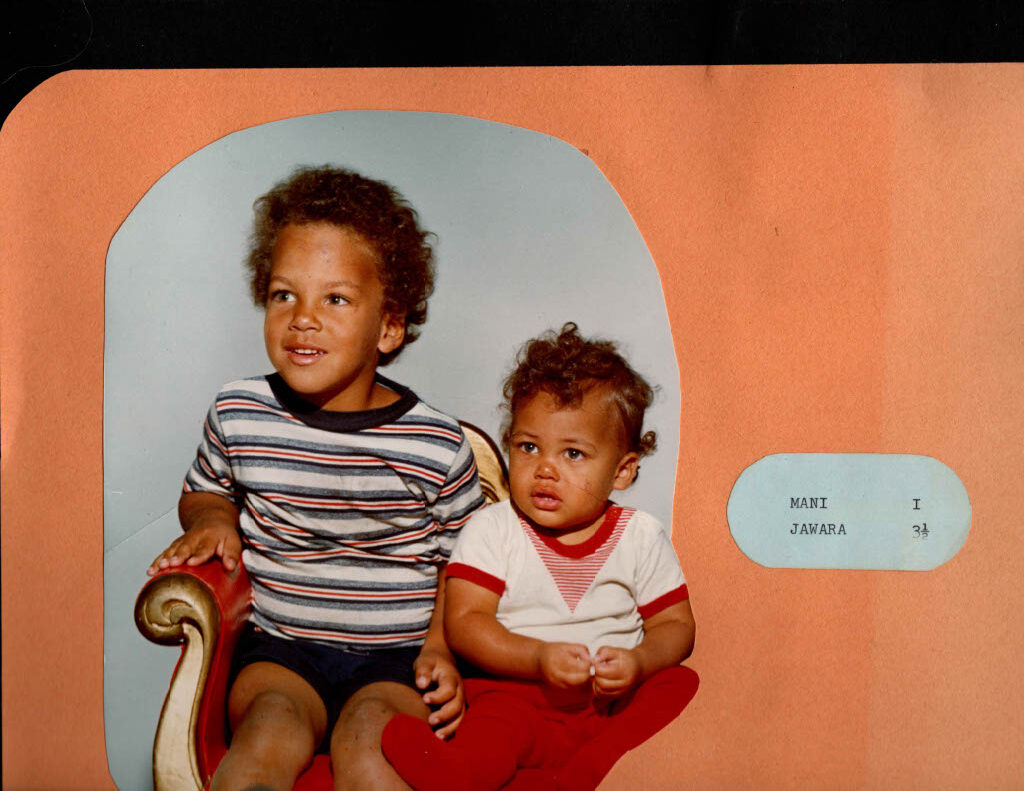

Jawara and Mani Sanford. Photo courtesy Betty and John Sanford.

“Jawara cost us $7,” Betty said with a smile.

Mani followed in 1974, born in South Korea.

“Mani cost $17,” she said. “Each felt like a million-dollar baby in a five- and 10-cent store.”

Still, racism occasionally pierced their insulated world. Once, dining out with baby Jawara, an older white couple sneered, “Disgusting.” Betty didn’t let it linger. “I told John, ‘This is what I meant about the challenges we might face.’”

Prejudice came from all sides. A Black passerby once shouted, “Looks like you picked from the bottom of the barrel.”

“I was sure they meant me,” John said. “But Betty thought they meant her. We never agreed — but we found a way to laugh about it.”

Raising biracial children in a shifting world wasn’t easy. Betty reflected on her regrets.

“They’re socialized Black and white,” she said. “But I wish I had taught them more Black history.”

John agreed. “I could have done a better job learning — and teaching — that myself.”

Despite challenges, their sons thrived, embodying the values their parents lived by: adaptability, pride, and resilience.

“We built a life together, no matter where we were,” John said. “We knew we could rely on each other. That made all the difference.”

A Love That Endures

By 2021, Betty and John Sanford had celebrated 50 years of marriage. Though pandemic restrictions canceled their party plans, they quietly commemorated the milestone with a labor of love—a pictorial history of their life together.

“We’re working on telling our story,” Betty said.

John and Betty Sanford at Kenan Research Library in McElreath Hall at Atlanta History Center, September 27, 2023. Photo courtesy Tiffany Harte.

Their marriage endured thanks to shared values, mutual respect, and compromise.

“Marriage isn’t all roses,” Betty said. “It’s trials and compromise — and the willingness to understand another’s point of view.”

John put it simply: “Concentrate on your spouse’s positives. Try to give them what matters to them — even if it seems silly to you. What matters is that you gave it.”

After 52 years, their affection remains evident.

“Hey, babe. I love you. Thank you. For 52 years,” John said.

Everywhere they went, they challenged societal norms—simply by being together.

“Love knows no boundaries,” John said. “I’ve always been proud to say, ‘This is my wife.’”

As Betty put it, “Our marriage wasn’t just about us. It was about the message we sent: that real love can transcend anything.”