The story of any Olympic Games includes the efforts of civic activism on the part of residents of the host city. Atlanta was no different.

Although the mission of the Games is to unify the world through sport, they are highly political for the local communities of the host city as well as participating nations from across the globe. On the local stage, the undertaking consumes economic resources, alters urban landscapes, and impacts labor markets. It also reveals the power dynamics of a host city’s leadership, displaying who is involved in decision-making and who benefits from big decisions.

From the Games’ earliest concepts through their production, residents across communities and economic classes of an Olympic host city find ways to join the conversation about how the experience can shape their future. Many support the Games and use the attention and resources to further their causes. Others voice opposition to the decision-making processes. Some collectively resist the efforts from leadership to change the places in which they live.

In the years leading up to the ’96 Games, national issues such as welfare and housing reform, disability rights, and LGBTQIA+ equality converged with Atlanta’s preparations as host city. As organizers of the Games planned for venues and global attention, residents not included in planning used the public platform to press for different types of change. They directed new attention to longstanding concerns and brought national issues close to home. Residents’ efforts resulted in different degrees of success, yet they serve as examples of how individuals can make their positions known and the ways through which social activism impacts a city and makes steps toward change.

Who wants the games?

As the Games have grown, public opinion about hosting the event has varied from excitement and honor to skepticism and apprehension. Political tensions and economic realities have turned some past Games into lessons for future hosts. At times, success stories have convinced city leadership that the risk was worthwhile. The scale of the Games makes them the most viewed sporting event on the planet. The push to “go bigger,” however, often deters cities from the commitments of being host. At nearly every bid cycle in recent decades, citizens in prospective cities have mobilized to express opposition, apathy, or concerns about their city entering the bidding pool. Their activism often affected the final selection.

There Are Two Sides to Every Medal | Melbourne: Committee to Oppose Holding the Olympic Games in Melbourne, February 1990 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Atlanta entered the candidacy process following the success of the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles. Those were the first Games to turn a profit in decades. The Atlanta Organizing Committee worked to show widespread excitement for the bid to the voting body of the International Olympic Committee. To the committee, public support was as important as a strong financial plan. Yet, Atlanta was not exempt from the opposition that all candidate cities experience.

Some of the earliest voices of dissent came from anti-poverty groups in the city, including Open Door Community, founded by the late Reverend Murphy Davis and her husband Ed Loring. Their position was fostered by a strong community of anti-poverty activism in Atlanta and across the nation from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. Post-World War II urban redevelopment programs were aimed at economic growth and improvements in housing for U.S. cities. Ultimately, these programs had a negative impact on many low-income and Black urban residents.

Murphy Davis standing in front of a list of executions that have taken place in the U.S. since 1977 Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, 1987 | Murphy Davis was born in 1948 and grew up in Louisiana and North Carolina. She was pursuing a career in theology when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Georgia’s law of Capital Punishment in 1976. She has worked for the abolition of the death penalty, housing the homeless, the Movement for racial justice, justice for the poor, and the abolition of war. Davis and her husband are founding partners of the Open Door Community, a diverse residential Christian community in downtown Atlanta. She passed away October 22, 2020. | Southline Press, Inc. Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Redevelopment projects cleared neighborhoods that were deemed slums or blighted to make way for large-scale infrastructure or new styles of residential communities. However, they rarely replaced the need for convenient low-income housing in the urban core. Affected residents found support, advocacy, and services through a series of community aid centers. These centers provided shelter, food, and income opportunities, as well as a united voice for engaging with city leadership and providing ways for members to become civically involved.

With firsthand knowledge of how big urban projects often result in negative impacts for Atlanta’s low-income neighborhoods and homeless populations, Open Door Community members voiced their concerns about Atlanta’s bid. They noted that common preparations for such big events include officials pushing for “vagrant free” zones that impact the homeless or those in need of shelters, and steep rent increases in previously affordable housing due to venue proximity.

They expressed concern that, as a private business enterprise, Olympic organizers were not subject to the oversight required of other city-changing project proposals. Forums for public input were not mandated as they were for projects directed by elected city officials. They also asserted that the projected economic impact of Olympic Games in prior host cities had not typically benefited residents that need it the most. Open Door listed worries about the city’s capacity for hosting large crowds, Atlanta’s summer heat, and the impact of leadership’s constant aim to expand the city’s profile—a uniquely strong sense of boosterism that has been able to cut through barriers to achieve impressive projects for Atlanta, but often leaves public input processes and consideration of effects outside the business community by the wayside.

Despite arguments made in early editorials and dissents, resistance to the Olympic bid in Atlanta did not gain considerable public or media attention. Atlanta’s organizers faced little noticeable local resistance. In comparison, fellow 1996 bid cities, such as Melbourne or Toronto, experienced protest groups that communicated early with the International Olympic Committee and fellow candidate cities. The delay in organized opposition was perhaps the result of strong boosterism surrounding the bid or that local activists failed to raise concern, believing Atlanta was too much of an underdog against the favored bid city, Athens, Greece.

Excerpt from Don’t Carry the Torch for World Domination: Oppose the ’96 Games Atlanta: Revolution Books Outlet, circa 1996 | 1996 Olympics Subject File – Criticism, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

After Atlanta won the bid, individuals began to coalesce around shared concerns about the impact of Olympic plans on the city. Members of the Open Door Community, along with Concerned Black Clergy, Emmaus House, and other community-aid organizations began campaigns to share information about the plans with vulnerable communities—including those experiencing homelessness to residents with historical barriers to participation in civic decision-making. Representatives from these and other groups formed the Olympic Conscience Committee to hold organizers of the Games accountable and ask for transparency throughout the process.

As plans continued, local groups aligned with national and international organizations voicing concerns about the impact of Olympic Games on host cities. The organizations regularly distributed leaflets and mailings to the Olympic organizers’ office. A cover letter that an Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) staff member attached to one such mailing stated: “This leaflet will make its mark as a part of the history of the Olympics, no matter how unwelcome it will be in some quarters.”

Continued activism experienced during the Olympic bid and preparations process, has contributed to broader public recognition of concerns about the cost of hosting the Olympic Games. These concerns have translated to media coverage, international coalitions advocating for reform, and increased analysis of the actual expenses. Many economists have analyzed records of past Olympic Games to assess actual costs to the host city and nation. Such assessments combine the organizing committee’s budget for the Games with additional government expenses for preparations. These total numbers have risen and fallen over recent decades due to different funding models, the size and number of existing facilities in a host city, and factors, such as security cost increases in a post-9/11 world. With each approaching Games, the discussions and analysis continue.

Comparative Graph of the Estimated Total Costs of Recent Olympic Games, 1972–2016 | Sources: Baade & Matheson, Flybvjerg & Stewart, Preuss, Zimbalist

Who is involved in planning?

One of the largest demands of the Games is space. Specialized venues require large tracts of land and can permanently change the nature of communities if located in urban or residential areas. Some places in Georgia wanted an Olympic venue to boost industry or add an attraction to their town. Historically, venues are most likely to negatively impact low-income communities that have been the focus of past urban renewal efforts. This is especially true in Olympic cities where organizers must build new venues rather than reuse facilities.

Residents in the Summerhill, Peoplestown, and Mechanicsville neighborhoods in Atlanta had suffered with the construction of interstate highways in the 1950s and with the presence of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium and its neighboring parking lots, built in the mid-1960s. Both projects were concluded with little input from the predominantly Black and low-income residents. These construction projects fractured the communities and forced the relocation of many residents. In addition, economic benefits promised by city officials failed to materialize for local businesses. When it was announced that Centennial Olympic Stadium would be built next to the existing stadium, residents of the nearby neighborhoods were easily doubted promises of economic revitalization and investment for their community.

Poor People’s Newspaper Atlanta: Emmaus House, March 1991 | Muriel Lokey Papers, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, MSS 96

Within one year of the bid selection, a coalition of these neighborhoods formed Atlanta Neighborhoods United for Fairness (ANUFF). Local activist Ethel Mae Matthews founded the coalition based on work as leader of the Poverty Rights Office at Emmaus House. She had also experienced housing loss and displacement during construction of the first stadium. As a longtime welfare rights activist, she was determined to ensure that her community did not suffer in the shadow of yet another stadium, or at least would not suffer quietly.

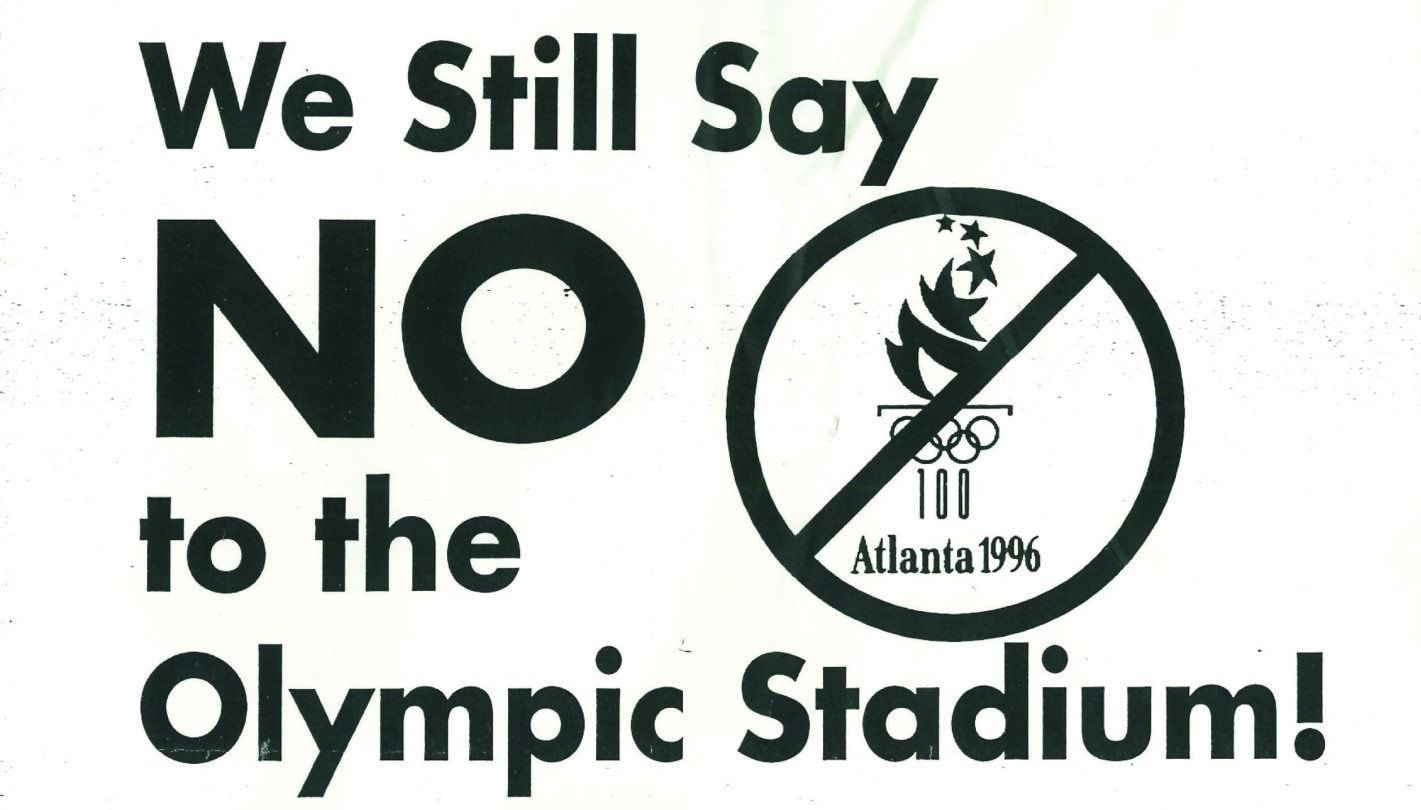

ANUFF organized pickets and protests at Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games headquarters and communicated with International Olympic Committee President Juan Antonio Samaranch. Their initial goal was to change the location of the planned stadium. They built a tent city at the stadium’s construction site and protested the official groundbreaking. This tactic ensured that organizers and city officials could not miss the concerned residents, and that their demands would need to be addressed before organizers could regain a clear construction site. With construction moving forward, many members of ANUFF began to meet with Olympic organizers and city officials to advocate for ways the stadium’s presence could benefit their neighborhood, from parking income to labor agreements.

We Still Say No to the Olympic Stadium Atlanta: Emmaus House, circa 1994 | Associations Subject File – Emmaus House, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

With all eyes on Atlanta, neighborhoods, including Summerhill, received more attention than they had previously received and as redevelopment projects created new housing stock and various groups pledged to direct money into the communities. Nevertheless, Centennial Olympic Stadium was built as planned in the parking lots adjacent to Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. The structure stands today under Georgia State University’s ownership. The stadium’s most recent transition once again revised neighborhood activism and participants used many of the same tactics to create a platform for their voice. Longtime residents of the area were quick to note that many of the promises of revitalization and community partnership by new ownership and development companies matched the promises made previously in the neighborhood’s history.

Meeting of Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games, Stadium Neighborhood Outreach Columbus Ward addressing the room, Atlanta, circa 1993 Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Debates over Olympic venue locations also occurred in affluent, white neighborhoods in Atlanta. Residents in North Brookhaven learned that Olympic organizers proposed their neighborhood’s Blackburn Park for tennis events. Many became concerned about resulting traffic, future commercialization of the venue, and the decision-making process that left out the neighborhood. A member of a Blackburn Park area neighborhood association commented to the Atlanta Constitution for an article on October 4, 1990:

“They never asked us if we wanted it here. We’re all for Dekalb getting a tennis center and being part of the Olympics, but just not right in the heart of a residential neighborhood.”

Homeowners banded together to pressure Olympic organizers to find another location despite Blackburn Park’s designation in the official bid proposal with the International Olympic Committee, an agreement that is known to be hard to change. Since there were several other options on the table for tennis locations, Olympic organizers were amenable to the concerns of the residents. The plans at Blackburn Park called for augmenting an existing tennis facility to increase it to Olympic scale. The revised plans located a standalone facility in the Stone Mountain area, which came to fruition for 1996, but lacked use after the Games.

What do we want the world to see?

Other communities in the Atlanta area seized the media attention of the approaching Games to add pressure to decision-making officials. This strategy was successful for Olympics Out of Cobb, a grassroots LGBTQIA+ organization that partnered with other advocacy organizations to challenge an anti-gay resolution adopted by the Board of Commissioners in Cobb County.

In the summer of 1993, a controversy about scenes of same-sex relationships in a local theater production led the Cobb County commissioners to adopt a resolution condemning the “gay lifestyle.” They also reduced the county’s arts budget for the 1994 fiscal year. Concerned residents organized the Cobb Citizens Coalition to fight the bigotry of their county leadership. A few months later, Cobb County received more attention when ACOG announced the Cobb Galleria as a venue for volleyball events.

Cobb Galleria Centre | Unidentified photographer, Cobb County, circa 1993 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Atlanta area activists Pat Hussain and Jon-Ivan Weaver considered the Olympic announcement to be an opportunity to create tangible consequences for the county’s resolution. They founded Olympics Out of Cobb to fight the selection of Cobb County as a recipient of Olympic attention and pressure the commissioners to rescind the resolution. Olympics Out of Cobb argued that allowing the county the participate in Olympic festivities would broadcast throughout the world the Games’ tacit endorsement of bigotry.

After officially forming in February 1994, Olympics Out of Cobb began a series of disruptive protests to generate media attention as part of the growing Olympic promotion. In addition to standard letter writing campaigns, Olympics Out of Cobb protestors organized a roadblock on I-75. They then appropriated the 1996 Olympic mascot, Izzy, to further place their efforts in the spotlight, dressing the character in a Ku Klux Klan robe to illustrate their message that if the Olympic presence remained in Cobb, the Games would be complicit in the county’s bigotry.

Izzy a Bigot? Olympics Out of Cobb pamphlet picturing appropriated Olympic mascot dressed in Ku Klux Klan robe Atlanta: Olympics Out of Cobb, circa 1994 Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing Papers and Publications, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, MSS 773

In July 1994, Olympic organizers relented, moving preliminary volleyball matches to the University of Georgia’s campus in Athens and out of Cobb County. In July 1995, there was brief uproar regarding potential plans to route the Olympic torch relay through Cobb County. With pressure from Olympics Out of Cobb members, Games organizers announced that Cobb County would not be included as part of the Torch Relay , avoiding more controversy.

Olympics Out of Cobb stickers and demonstration poster Atlanta: Olympics Out of Cobb, circa 1994 Atlanta Lesbian and Gay History Thing Papers and Publications, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center, MSS 773

How do we make space for everyone?

Other groups used the Olympic spotlight to advance longstanding causes and ensure the project of preparing for the Games was completed with considerations for equity and accessibility.

In the 1970s and 1980s, advocacy for independent living for disabled individuals progressed toward federal legislation. An active disability rights community formed in Atlanta to push the city to adapt public transportation for disabled access and advocate for equal opportunities for disabled citizens. Passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 created additional federal support for this work. The selection of Atlanta as Olympic host set in motion a quest for the Paralympic Games as well as action to ensure that disabled populations would be adequately considered in all the planned events and new venues.

Meeting of Atlanta Committee for the Olympics Games, Committee on Disabled Access L to R: Gene Dew, Dew Enterprises; Shirley Franklin, Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games; Zebe Schmitt, Governor’s Council on Developmental Disabilities Unidentified photographer, Atlanta, circa 1992 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Atlanta’s Olympic organizers established a volunteer Committee on Disability Access to consult about the needs of the disabled community. Frustrated with the level of attention Olympic organizers gave their recommendations, they joined with activists from other disability rights movements in Atlanta to stage a series of demonstrations in December 1993 at ACOG headquarters and the Georgia Dome to make their concerns known.

The protests highlighted ACOG’s limited record of employing disabled people, as only two of nearly 500 staff members were disabled. They also lobbied for labor agreements and documented the failure in planning accommodations for deaf spectators and ticket purchases.

The activists continued to work with the Olympic organizers, and many found positions with the Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee, as disability rights advocacy became a major mission of the 1996 Paralympic Games. In advance of the Games, the organizing committee planned the Third Paralympic Congress, a multi-day conference that held talks and workshops on advancing political and economic empowerment for the disabled community.

Scot Hollonbeck, Paralympian, speaking about the impact of Atlanta’s Games and disability rights advocacy Excerpt from an oral history interview, 2005 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Different facets of the same city

The project of hosting the Olympic Games is one with great impact on urban communities, regardless of the city or nation. With the short timeline, influx of resources, and long list of requirements and preparation commitments, planning regularly takes place in a top-down fashion. Despite this ever-present power structure, stories of everyday citizens are woven into Atlanta’s chronicle as host city. Being an active citizen can come in many forms, including disagreeing with and speaking out against local policy or leadership.

For some, securing the Olympic Games was an opportunity to change the face of Atlanta for the better. Nevertheless, residents across the city who disagreed with either the plans or process made their dissent known.

Movements for change are often built from the ground up and rely on individuals who speak out. What can we learn from stories of dissent? How can we still hear them today?

Learn more about the social activism surrounding the Games in Atlanta ’96: Shaping an Olympic and Paralympic City. Our new signature exhibition tells new stories and expands on memories of the Games, placing Atlanta’s Olympic and Paralympic histories in the context of the city itself. Drawn from Atlanta History Center’s distinctive collections, the exhibition creates a visitor experience coupling iconic and unexpected objects, archival materials, and still and moving images along with specially developed touchless interactive experiences. The exhibition invites visitors to examine the people, events, and decisions from recent history that shaped the Atlanta we know today.

Additional. Resources.

In memoriam: Murphy Davis (1948-2020)

Articles + Exhibitions

- 90.1 WABE | As Atlanta Grew, Rev. Murphy Davis Ensured City’s Homeless Stayed In View

- Christian Science Monitor | Can Paralympics advance disability rights in Brazil?

- Georgia State University Library, Out In The Archives Exhibition | Cobb Citizens Coalition and Olympics Out of Cobb

- Los Angeles Times | Olympian Test of Atlanta’s Mettle : Summer Games: The elation of being named host of 1996 event has been dampened by bickering, power struggles and protests over venue sites

- The Washington Post Magazine | The Price of Gold

- WBUR Boston | How The Olympics Changed Atlanta, And What Boston Could Learn

Books + Scholarly Publications

- The Americas, journal | Showcasing the ‘Land of Tomorrow’: Mexico and the 1968 Olympics

- Jules Boykoff | Activism and the Olympics: Dissent at the Fames in Vancouver and London

- Southern Spaces, journal | Whatwuzit?: The 1996 Atlanta Summer Olympics Reconsidered

- The New School | Acts of Olympic Dissent

Major support of this exhibition has been generously provided by the James M. Cox Foundation, Marine and John Fentener van Vlissingen, Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, The Coca-Cola Company, Martha and Billy Payne, The UPS Foundation, Martie and Dennis Zakas, and The Rich Foundation.