It’s 2024! As part of our programs this year, Atlanta History Center is bringing back Party with the Past, an event series visiting historic sites around the city to highlight their stories.

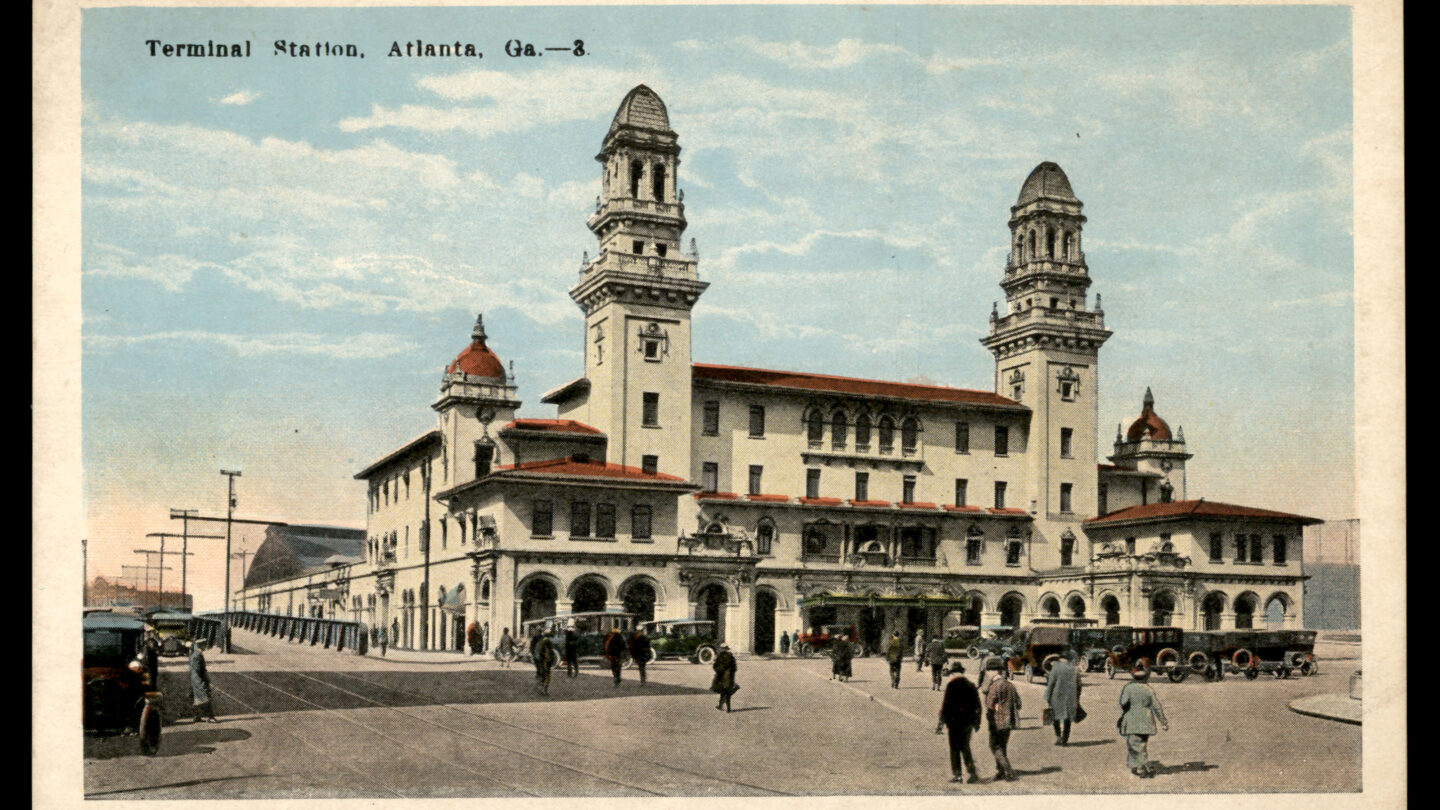

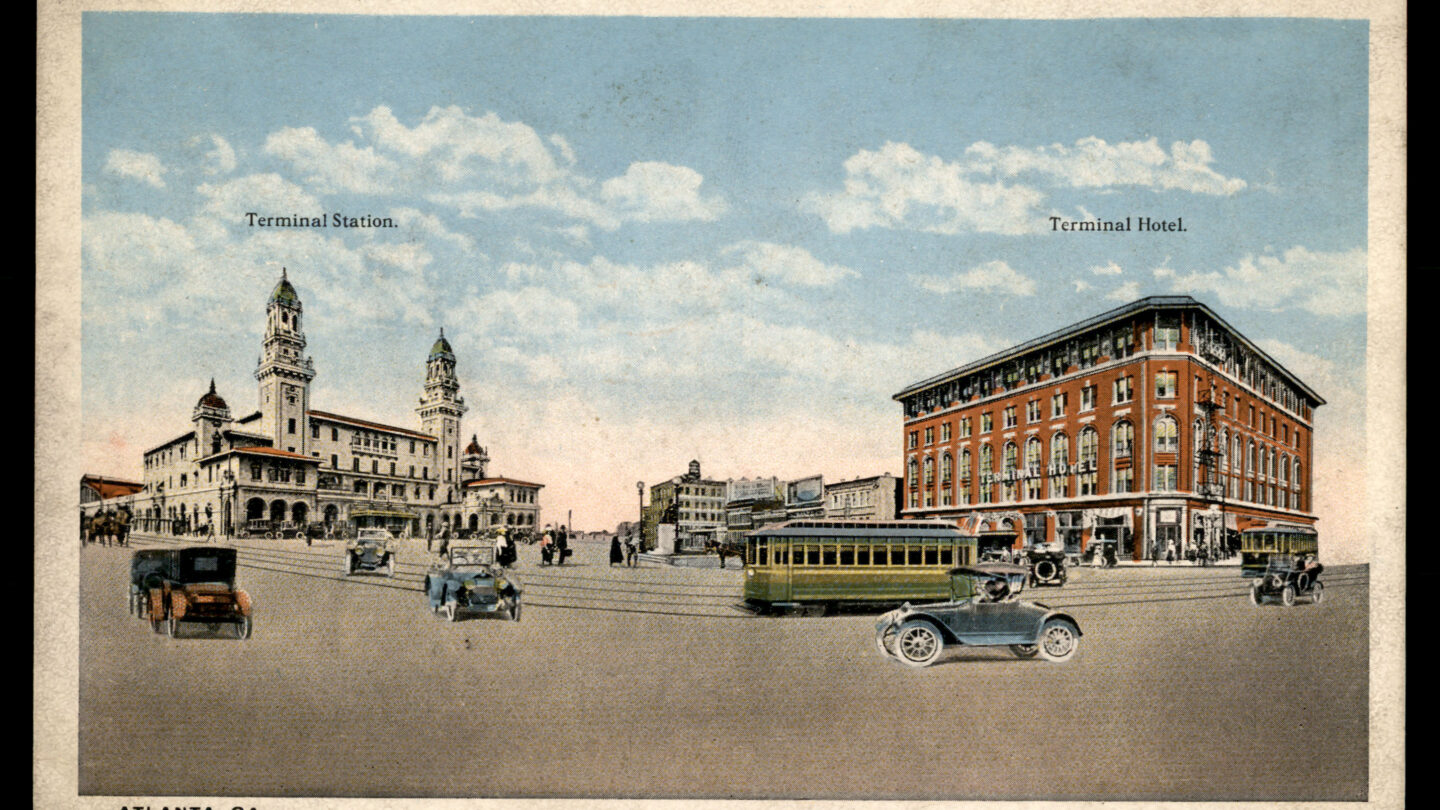

This postcard from the early twentieth century shows Terminal Station alongside the Terminal Hotel, another Atlanta rail hotel on the edge of Hotel Row that was lost in a fire. Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

On Wednesday, September 18th, we’re hosting a block party on Broad Street, in partnership with South Downtown and Central Atlanta Progress. We will be learning about one of the oldest parts of Atlanta through a combination of expert speakers, walking tours, and a one-night-only pop-up exhibit chronicling the history of the neighborhood.

Hotel Row is an iconic feature of South Downtown. Located along Mitchell Street at its intersection with Forsyth Street, this block of historic retail and hotel spaces was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1989. For the first half of the twentieth century, its beautifully designed hotels, situated just a few blocks from Terminal Station in one of Atlanta’s most vibrant neighborhoods, provided tourists and railroad employees alike a place to stay while visiting the city. The buildings that make up Hotel Row generally date to shortly after the 1908 fire in the neighborhood but one, an iconic building that did not begin its life as a hotel at all, is significantly older. Concordia Hall was completed in 1892 as an opulent clubhouse and ballroom for one of Atlanta’s oldest Jewish social organizations – the Concordia Association.

The Concordia Association

The Concordia Association was founded in 1866 by brothers Abraham, Sigmund, and Louis Rosenfeld and their friends and business partners. The Rosenfelds came to Atlanta after the Civil War, in which all three had fought – Abraham for the Confederacy and Sigmund and Louis for the Union.1 Soon after his arrival in the city in 1865, Abraham opened a men’s clothing store at 24 Whitehall Street. When Sigmund joined him in business, he changed the shop’s name from Gate City Clothing Store to A&S Rosenfeld Co.2 The brothers were members of several civic and social organizations, including the Hebrew Benevolent Society, and decided to found an organization that would combine cultural interest and their Jewish faith.3 Thus, the Concordia Association was born.

The Association organized a variety of activities for its members and the public, including dramatic performances (its amateur theater troupe was respected throughout the city), literary and musical soirees, balls, card-playing, and debates.4 In its early decades, the Concordia Association was headquartered in several rented locations around Downtown. Their first headquarters hosted not only the Concordia Association but also Abraham Rosenfeld’s wedding to Emilie Baer in 1867 – the first Jewish wedding in Atlanta since the Civil War. Their most notable early clubhouse was, perhaps, the third floor of the Grant Building (confusingly also frequently referred to as Concordia Hall before it was demolished in the late 1960s) at No. 40 Marietta Street, near City Hall.5 The building rented some of its office space to a young lawyer who had recently moved to Atlanta and briefly set up a practice in 1882: future president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson.6

Concordia Hall

The Concordia Association grew as Atlanta’s Jewish community grew. Its members were primarily young businessmen from the German and Hungarian Jewish communities and their families.7 By the early 1890s, it was clear that the Association, which boasted over one hundred members, needed more space, and was successful enough to fund its own expansion.8 Two architectural firms made bids to build the Association a new clubhouse. One, E.G. Linde, proposed a building on the corner of Brotherton and Whitehall Streets, estimating a cost of $60,000. The other, Bruce and Morgan, proposed a building at Marietta and Forsyth Streets with an estimated cost of $40,000. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Association went with the $40,000 plan.9 The new Concordia Hall was, according to The Southern Architect, “first-class,” and completed around 1892.10 It would host a few commercial spaces for rent on the first floor, and the second and third floor would be devoted to the Association. These floors included a banquet room, parlor, library, and an opulent ballroom that could also serve as a theater.11 The outside of the building was just as grand as its interior. It featured all of the fashionable Victorian finishes of the day, including a turret.12

This architectural drawing, published in The Southern Architect and Building News in 1891, shows Concordia Hall as architectural firm Bruce & Morgan intended to build it. The turrets and most of the decorations were removed in the early twentieth century. Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The Concordia Association moved in by early 1893.13 When announcing its opening banquet in March of 1893, the Atlanta Journal noted that “[t]his hall is said to be a marvel of beauty and elegance in finish” and listed the toasts that would “have response from prominent citizens: Concordia, City of Atlanta, State of Georgia, Our new Club, Our Ex-Presidents, Absent friends, The Press, Our Guests, The Ladies.”14 Over the next ten years, the Association and various renters hosted countless events at Concordia Hall. The Zouave Club, for example, gave a rather exciting dance there in August of 1894, in which “five well known young men” were arrested after getting into a fight at the front door in which one was badly injured after three of the men, who didn’t have tickets to the dance, tried to enter after being rebuffed by the door keeper.15

Luckily for the Concordia Association and its headquarters, most of its events were more sedate. In 1895, Samuel Gompers, a prominent union activist and former president of the American Federation of Labor spoke at Concordia Hall, and a few months later, Atlanta celebrated its first Labor Day with a parade march that circled Concordia Hall’s block.16 In 1899, it hosted a two-week Bazaar for the Hebrew Orphan’s Home.17 It continued to host wedding receptions as well. In 1896, Miss Carrie Dann and Mr. Louis S. Byck hosted a banquet and wedding reception there that made it into Atlanta’s society pages.18 In addition to these more specialized events, Concordia Hall hosted regular balls, plays, and Concordia Association events and meetings.

The Concordia Association was not to occupy Concordia Hall forever. It began to struggle with its finances and member retention as its founding generation died. Though these struggles eventually pushed the Association out of Concordia Hall sometime between 1901 and 1904, it did not end it completely. The Association reorganized in 1904 as the Standard Club, which still exists today in nearby Johns Creek.19

In 1905 Terminal Station opened just a few blocks from Concordia Hall, and the already successful area around it began to boom. Just a few years later, in 1908, the Marietta/Forsyth block on which Concordia Hall sat suffered a setback to its growth: a fire broke out that burned down every building on the block, except for Concordia Hall, which was protected by its thick brick walls.20 When new tenants moved in to replace those that had been lost in the fire, a theme quickly became clear: of the five new buildings that were built after 1908, three were hotels. The Gordon Hotel, the Sylvan Hotel, and the Scoville Hotel, as identified on the National Register of Historic Places, shared the rest of the street with two small commercial buildings, and provided rooms to rail passengers and employees.21

Southern Railway

When the Concordia Association moved out of Concordia Hall, Southern Railway, one of the many railroad companies whose trains pulled into nearby Terminal Stations daily, acquired the building. The company knew just what it would do with its new acquisition. Like the other buildings on Hotel Row, the lower stories of Concordia Hall would remain retail spaces, and its upper two floors would become hotel rooms – referred to as “the Railroad YMCA” – specifically designed for Southern Railway employees who were stopped over in Atlanta.22 Concordia Hall’s already lovely recreational facilities would remain the same in order for guests to make use of them, while the now obsolete ballroom would be converted into over twenty bedrooms.23 Its ostentatious Victorian façade would also be subject to renovations. Most of it – the turret in particular – was removed, making the building significantly more stylish to early twentieth century eyes and matching it to the new hotel buildings popping up down the block.

Southern Railway’s decision to take over Concordia Hall was a profitable one. By January of 1914, 4,396 freight trains and 152 passenger trains stopped in Atlanta daily.24 South Downtown’s proximity to Terminal Station meant that it prospered in the resulting boom. Things only got better in the 1920s when the Spring Street Viaduct was opened, allowing motorcars to reach Hotel Row and its accommodations with ease.25

Hotel Row circa 1940, bustling with cars and businesses. The building at the far end of the street is Concordia Hall, at that point the Railroad YMCA. Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

From the 1920s to the 1940s, Concordia Hall and the area surrounding it continued to flourish. The Hall itself remained an icon in the area. Newspapers often used it (and the building the Association had shared with President Wilson, called “old Concordia Hall”) as reference points for various events and locations around Downtown Atlanta.26 There is no evidence that Southern Railway, upon opening its hotel, changed the name of the building, unlike the other hotels on Hotel Row, which changed names when they changed hands.

After the Railroad

After World War II, as Americans began to travel more by car or airplane than by train, South Downtown and Hotel Row began to change. The area declined throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and Hotel Row was especially hurt by the closure of Terminal Station in 1972, which robbed it, and the Railroad YMCA at Concordia Hall, of its guests. Though the hotel above the retail spaces in the hall was closed, Concordia Hall managed to maintain retail tenants. In the late 1980s, as the center of Downtown Atlanta continued to move north, and the area around Hotel Row continued to decline, Concordia Hall became a significant part of the state of Georgia’s push to have Hotel Row placed in the National Register of Historic Places. The building’s age, its relationship to a significant community organization as well as the railroad, and its distinct architecture were emphasized by the state when it made its bid.

The front doorway of Concordia Hall in 1970. Its elaborate decorations are remnants of the building’s original façade. The lyre that formed the centerpiece of the Victorian decorations that remained on Concordia Hall after its early twentieth century renovations was the symbol of the Concordia Association. Courtesy of Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

In 1989, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources’ bid to place Hotel Row – and Concordia Hall – on the National Register of Historic Places succeeded. The buildings were designated historic landmarks for their architecture and their role in a significant period of Atlanta’s history. Hotel Row’s place on the National Register helps to ensure that the community is aware of its significance – listing on the Register comes with a plaque – and makes it eligible for federal funding to renovate or maintain the site to ensure its future preservation.27

Today, Concordia Hall continues to serve as a retail space in South Downtown. The building, which was long owned by the Teilhaber family – owners of longstanding Atlanta business Friedman’s Shoes – was recently sold to South Downtown Atlanta, our partner in hosting this Party With the Past. Concordia Hall is now home to several businesses: Atlanta Cleaners, Swift Bail Bonding, and Friedman’s Shoes, which opened in 1929, and has been a tenant of Concordia Hall since the 1960s. Much like the railroad, Friedman’s has continued to bring all sorts of interesting people into Concordia Hall’s orbit. They count numerous sports stars, including Shaquille O’Neal and Charles Barkley among their clients, and have sold shoes to several members of the Rolling Stones.

Concordia Hall is just one of many landmarks whose rich history we will explore this month. Party with the Past: South Downtown Block Party will be Wednesday, September 18th, from 6:30-9:30pm. Our party features a temporary exhibit that dives into the history of the rest of the neighborhood, walking tours, and more. We hope you will join us.

Notes

- Dorothy Loring Eisman-Kaufman, “Typed History of the Rosenfeld Family,” April 22, 1981, Rosenfeld Family Genealogy File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

- Eisman-Kaufman.

- Eisman-Kaufman.

- Eisman-Kaufman.

- Atlanta Historical Society, “Notes on the History of Concordia Hall,” circa 1968, Concordia Hall: Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center; “Town Topics,” The Atlanta Constitution, April 4, 1877, 03, https://www.newspapers.com/image/26777885/.

- “Town Topics”; Atlanta Historical Society, “Scan of an Article Titled ‘Woodrow Wilson’s First Law Office Occupied by Ivan Allen,’” 1918, Concordia Hall: Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places,” August 29, 1989, Subject File, Hotel Row, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center; Atlanta Preservation Center, “Concordia Hall: Icon of Jewish Contribution to Early Atlanta,” 2017, Concordia Hall: Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

- Atlanta Historical Society, “Scan of an Article from The Southern Architect,” September 1892, Concordia Hall: Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

- Atlanta Historical Society, “Notes on the History of Concordia Hall”; Atlanta Historical Society, “Scan of a Page from ‘The Southern Architect,’” September 1892, Concordia Hall: Subject File, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

- Atlanta Historical Society, “Scan of a Page from ‘The Southern Architect.’”

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places,” 12.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places.”

- Atlanta Historical Society, “Notes on the History of Concordia Hall.”

- “To Open the New Club: The Elegant Concordia Hall’s Opening,” The Atlanta Journal, March 25, 1893, https://www.newspapers.com/image/969476026/.

- “Five of Them Fought At a Ball at the Concordia Hall Last Night,” The Atlanta Journal, 1, accessed August 21, 2024, https://www.newspapers.com/image/969461031/.

- “Labor’s Great Pageant: Extensive Preparations for the Celebration of Labor Day in Atlanta,” The Atlanta Constitution, August 25, 1895, https://www.newspapers.com/image/26840523/.

- “Brilliant Bazaar for Orphan’s Home,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 26, 1899, 26, https://www.newspapers.com/image/34209974/.

- “Gossip of People and Events,” The Atlanta Journal, February 6, 1896, 06, https://www.newspapers.com/image/968841721/.

- “Club History – The Standard Club GA,” accessed August 28, 2024, https://www.standardclub.org/club-history.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places.”

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

- “Railroad Y.M.C.A. Now in New Quarters,” The Atlanta Constitution, November 23, 1917, https://www.newspapers.com/image/34141969/.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places.”

- Jackson McQuigg and Claire Haley, “Railroads At Your Service,” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 9, 2022.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources, “Announcement of Listing in the National Register of Historic Places.”

- “It’s Good Business To Tour Downtown,” The Atlanta Constitution, May 5, 1979, https://www.newspapers.com/image/398947947/; “Railroad Y.M.C.A. Now in New Quarters.”

- “FAQs – National Register of Historic Places (U.S. National Park Service),” accessed August 29, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/nationalregister/faqs.htm.