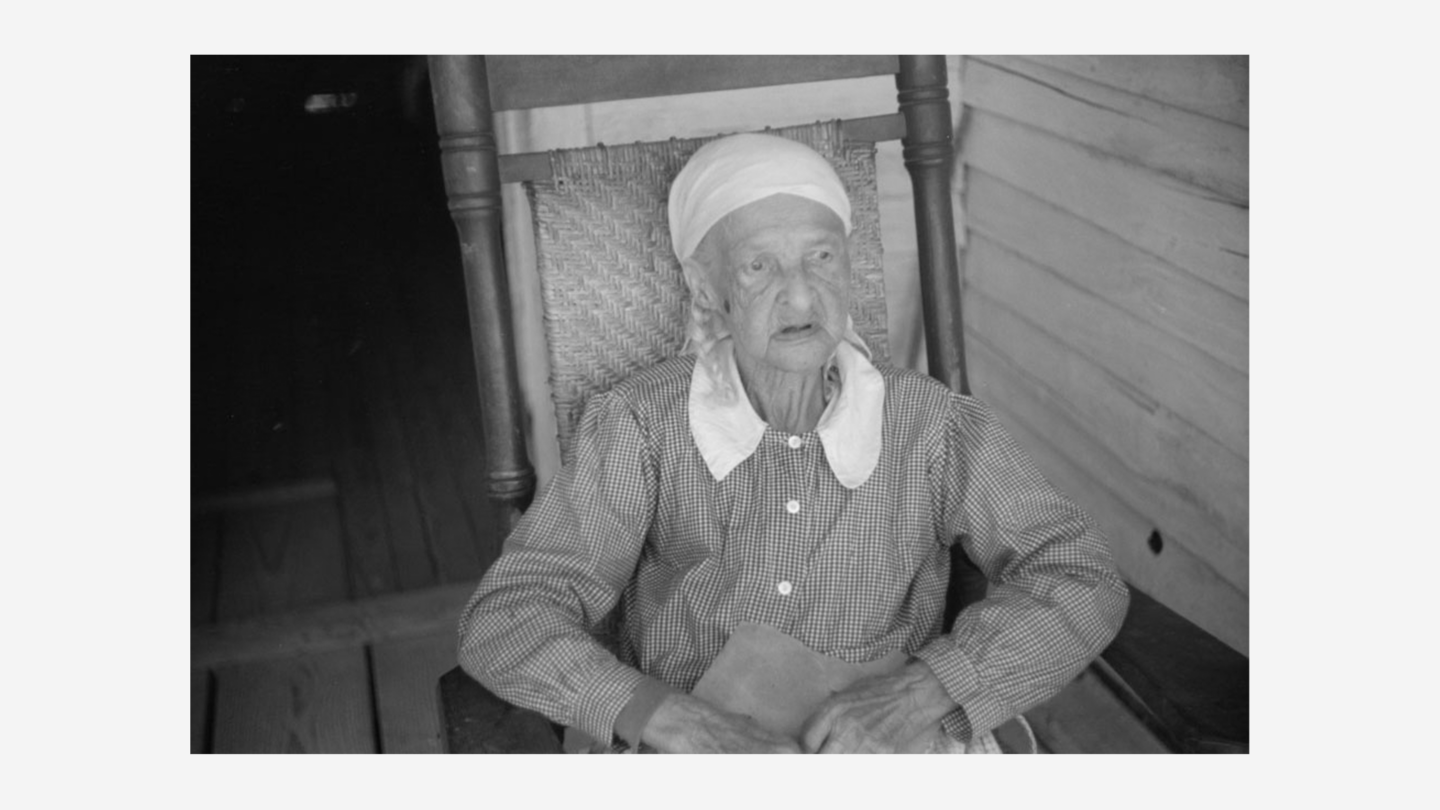

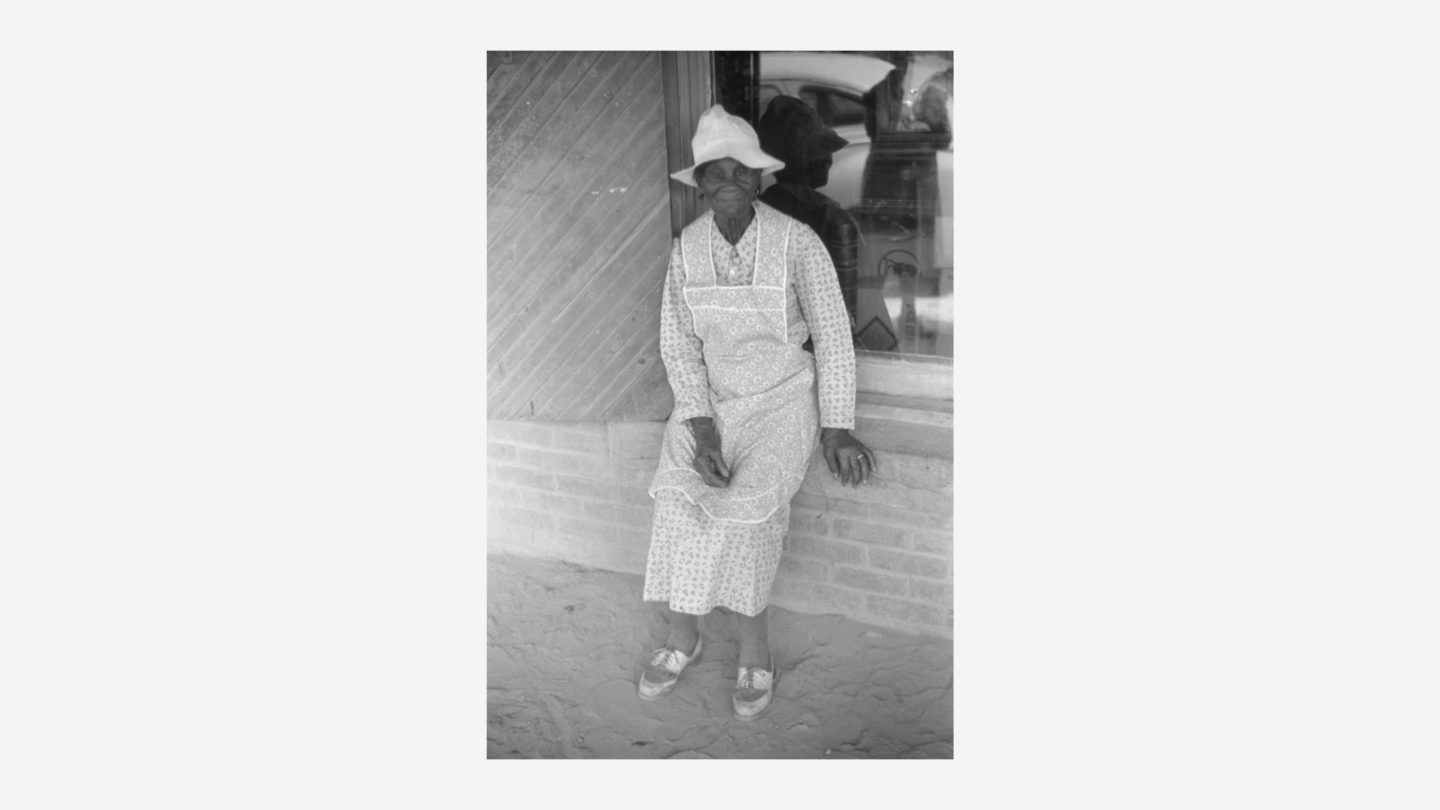

A freedman and his wife on steps of plantation house now in decay in Greene County, Georgia, 1937. Dorothea Lange, Library of Congress

Antebellum Georgia was a hub for the domestic slave trade in America due to the state’s reliance on cotton as a cash crop. Several Georgia cities, including Atlanta, Macon, Augusta, Columbus, Milledgeville, and Savannah, hosted slave auctions. One of the largest slave auctions in the country, where auctioneers sold 429 enslaved African Americans, took place near Savannah in 1859. Only in 2022 did research uncover a larger auction held in South Carolina.

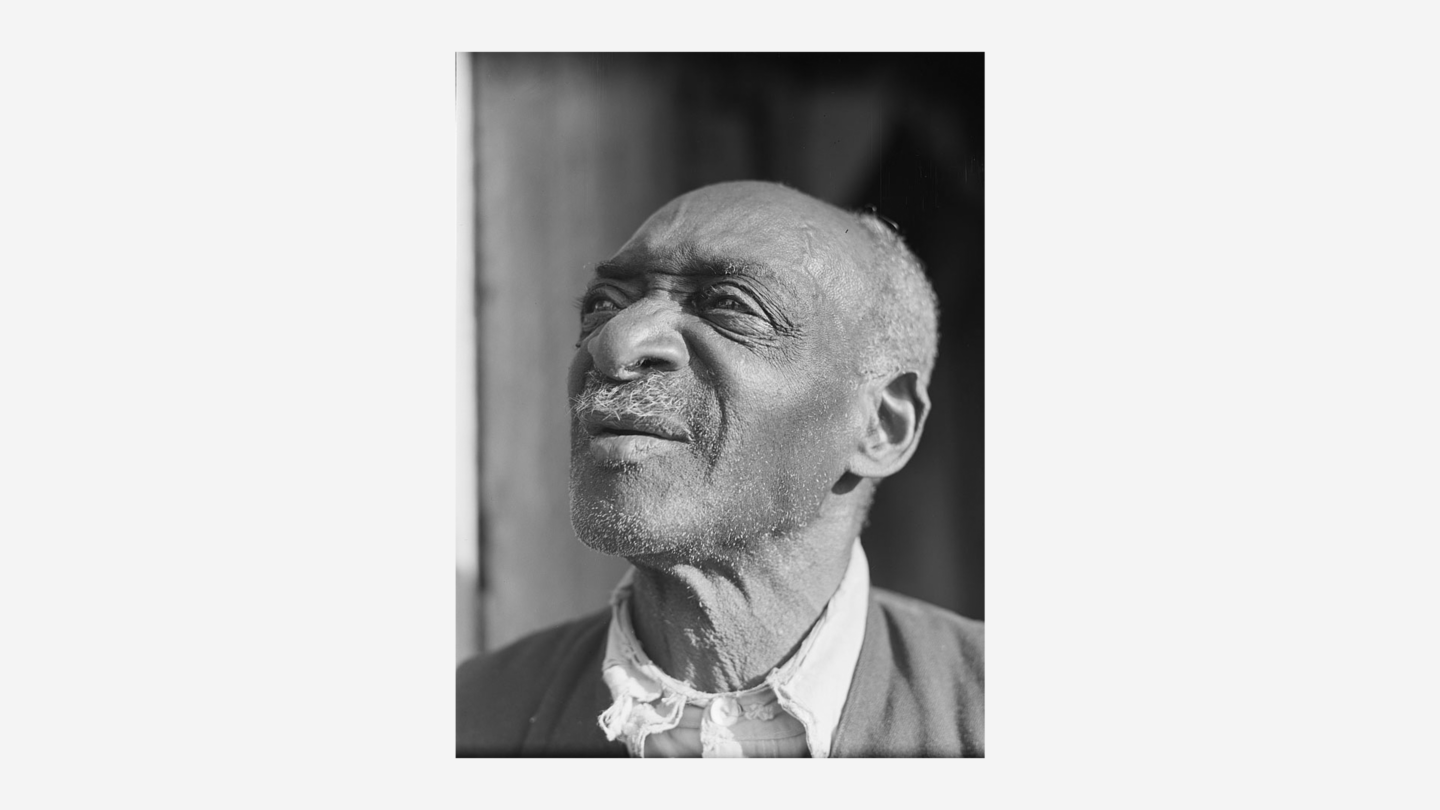

An abandoned slave pen in Thomasville, Georgia. Joseph John Kirkbride, Library of Congress

These auctions were extremely dehumanizing. Enslaved people were held in crowded pens, or “waiting cells,” before being transported to market in chains. They were frequently abused in the pens and during transportation. At auction, sellers or buyers could separate parents from children, brothers from sisters, and husbands from wives. The trauma of familial separation with no guarantee of ever seeing a loved one again was yet another injustice inflicted on enslaved African Americans.

Finding Lost Friends

After emancipation, the newly freed sought to find lost family members, sometimes continuing their search for decades. The Freedman’s Bureau, a federal agency established to assist formerly enslaved people, held scant records of individuals and proved to be of little help. This is where Black-owned newspapers such as the Southwestern Christian Advocate stepped in. These publications helped reunite African American families by running “lost friend” notices. These ads typically listed the relatives’ names, ages, and last-known locations and requested that any sightings be reported to the address listed in the ad.

The Lost Friends Database has compiled every advertisement from the Southwestern Christian Advocate asking for the location of loved ones separated by the slave trade from November 1879 to December 1900. It began as a digital companion to the Historic New Orleans Collection’s Purchased Lives exhibition in 2015, which detailed the horrors of the domestic slave trade in New Orleans. Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University Library, Bridwell Library, and Southern Methodist University digitized the advertisements.

Atlanta’s Lost Friends

Listed below are “Lost Friends” advertisements from or related to Atlanta. These newspaper advertisements feature stories of Black families taking steps to reunite after enduring the cruelty of the domestic slave trade. Black churches and Black-owned newspapers facilitated these reunions by spreading messages via print and word of mouth, strengthening community ties among Black Americans in the South.

Enslaved children were at high risk of being separated from their families because enslavers would give them away as “gifts.” To slave traders, youth did not diminish an enslaved person’s labor value, so in some advertisements, mothers such as Harriet Williams of Rosedale, Louisiana, searched for their children. Williams was separated from her 4-year-old daughter Mary.

A “lost friends” advertisement from the September 23, 1880, Southwestern Christian Advocate

In other advertisements, petitioners such as Rebecca Anderson in Tyson, Texas, sought their entire families. In her ad, Anderson recounted being separated from her siblings and parents when her enslaver sold her and her brother to another enslaver, who sent them to Texas to be bought by yet another enslaver.

A “Lost Friends” advertisement from the November 5, 1891, Southwestern Christian Advocate

Black churches were critical resources for Black families separated by the slave trade, spreading messages via word of mouth. As more than 500 preachers across the southern United States read the Southwestern Christian Advocate, some petitioners asked local churches for help finding their loved ones. In her advertisement, Jane Moultrie asked church ministers in Atlanta to read her plea for her lost mother and siblings from the pulpit.

A “Lost Friends” advertisement from the July 24, 1884, Southwestern Christian Advocate

Newspaper advertisements were vital when searching for lost loved ones taken across state borders. A.J. Simpson, from Doyle Station, Tennessee, was separated from his sister, Sarah Ann Simpson, at the age of 7, but he still yearned to find her after he was emancipated.

A “Lost Friends” advertisement from the October 1, 1891, Southwestern Christian Advocate.

Isaac Allen’s “Lost Friends” advertisement mentions that his brother Rufus Allen was a member of the 30th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which served the Union during the Civil War. This made Rufus one of the 179,000 Black soldiers who served in the military during the war. The advertisement also notes that Isaac and Rufus escaped slavery with General William Sherman’s army. On the other hand, Isaac’s brother James disappeared after leaving Chattanooga for Atlanta.

A “Lost Friends” advertisement from the November 24, 1881, Southwestern Christian Advocate.

The “Lost Friends” advertisements in the Southwestern Christian Advocate and similar newspapers are an enduring sign of the hope and longing for a better tomorrow that sustained Black Americans, even during the cruelest periods of their history. They stand as monuments of hope, resilience, and community relations.