A view of the site when it was being used by Southern Iron Equipment Company, circa 1979. Stephen Goldfarb Photographs, Kenan Research Center.

It’s 2024! As part of our programs this year, Atlanta History Center is bringing back Party with the Past, an event series visiting historic sites around the city to highlight their stories.

A key part of understanding Atlanta today is learning about the industries that shaped it. That’s why in May we will be hosting a party at AlcoHall at Pullman Yards, located in the Kirkwood Historic District. For over a century, this 27-acre plot of land has adapted time and again to suit a variety of industries and characters.

Let’s look at how Atlantans throughout history have used this site to suit the needs of the time. Fair warning: we will be talking about a lot of people named Nathaniel and George.

1904–1926 Pratt Engineering & Machinery Company

The original 5 buildings onsite are from Pratt Engineering and Machinery Company, which primarily made equipment for chemical manufacturing plants. Pratt Engineering was a collaboration between two influential Georgia families: the scientific Pratts and the wealthy Hurts.

One of the inventions patented by George L. Pratt, a new pulverizing machine which was later used in the sugar refinery plants Pratt Engineering and Machinery Company constructed, approved July 17th, 1906. US Patents Office.

Who were the Pratts?

By the time brothers Nathaniel Palmer Pratt and George Lewis Pratt started their company, the Pratts were already a well-known Georgia family. Their father, Dr. Nathaniel Alpheus Pratt, was a chemist and former Confederate who was the Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Nitre and Mining during the Civil War, responsible for securing chemicals necessary for the manufacturing of gunpowder, and later became the State Chemist of Georgia. Their grandfather, Reverend Nathaniel Alpheus Pratt, was an early citizen of Roswell. The reverend officiated the wedding of Martha Bulloch and Theodore Roosevelt Sr., the parents of our 26th President.

The children of Dr. Nathaniel Alpheus Pratt soon established themselves in the southern scientific community. Eldest son Nathaniel Palmer Pratt was the founder and president of N.P. Pratt Laboratory, where he employed his brother George and other members of the family. By 1900, it was one of the largest chemical companies in the South and rapidly expanding into multiple industries.

Their engineering department, led by George, designed the specialized equipment used by other company departments. The brothers soon began selling these machines to other factories. Both men held various patents in chemistry and engineering, which led to early success.

Opening Pratt Engineering and Machinery Company

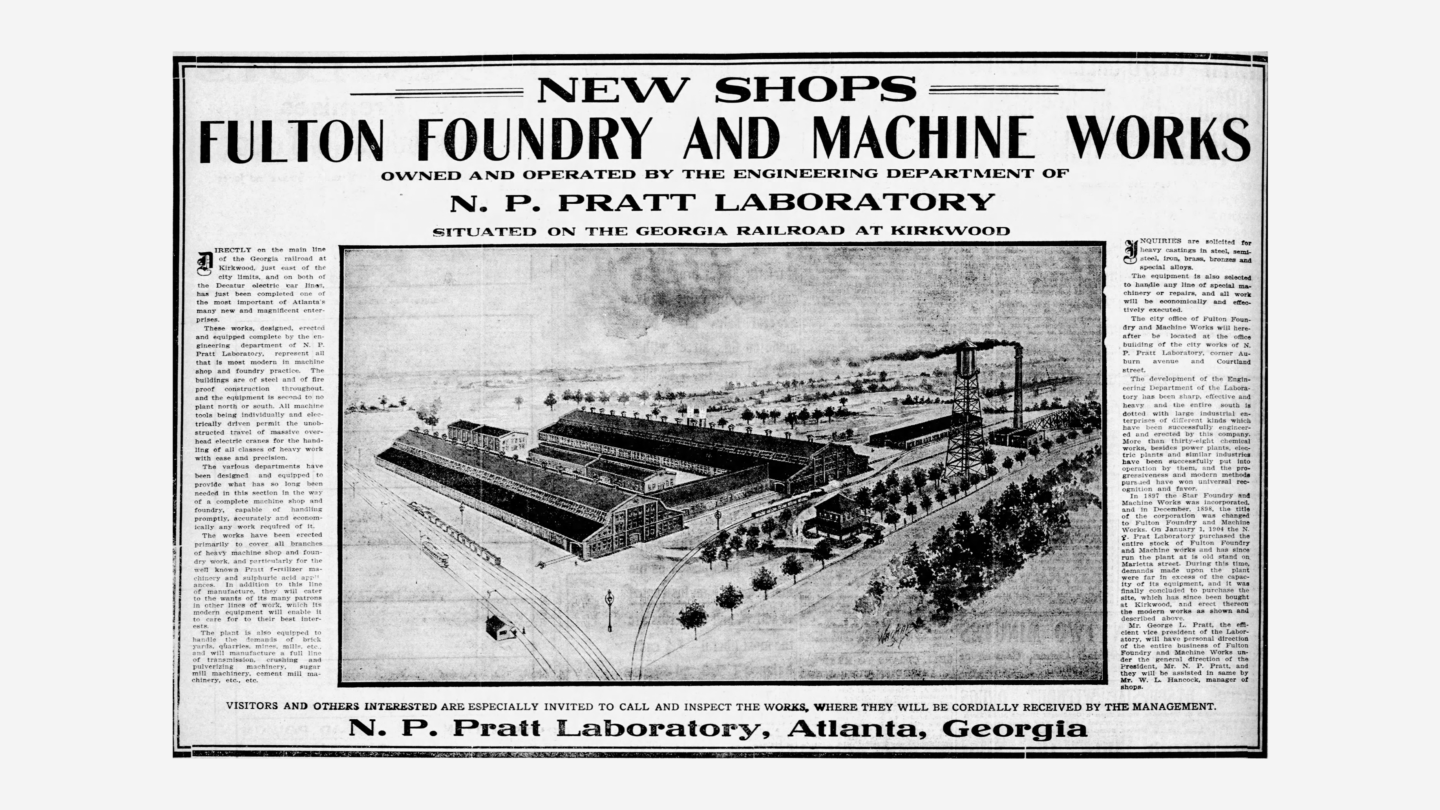

The Pratt brothers bought the future Pratt-Pullman site to expand on George’s work. In 1904, N.P. Pratt Laboratory purchased a controlling interest in Fulton Foundry and Machineworks and moved it from its original location on Marietta Street to a state-of-the-art facility they built in Kirkwood.

Some residents in the then upper-class Kirkwood expressed concern about the investment. Kirkwood was seeking a town charter at around the same time, and according to contemporary newspaper coverage, some of Kirkwood’s residents were motivated to incorporate as a town because they wanted to prevent the construction of the new Pratt factory. In 1904, Kirkwood successfully incorporated—but the Pratt-Pullman site still opened to the public in June 1906 as Fulton Foundry and Machineworks, with George Pratt in charge of the daily operations.

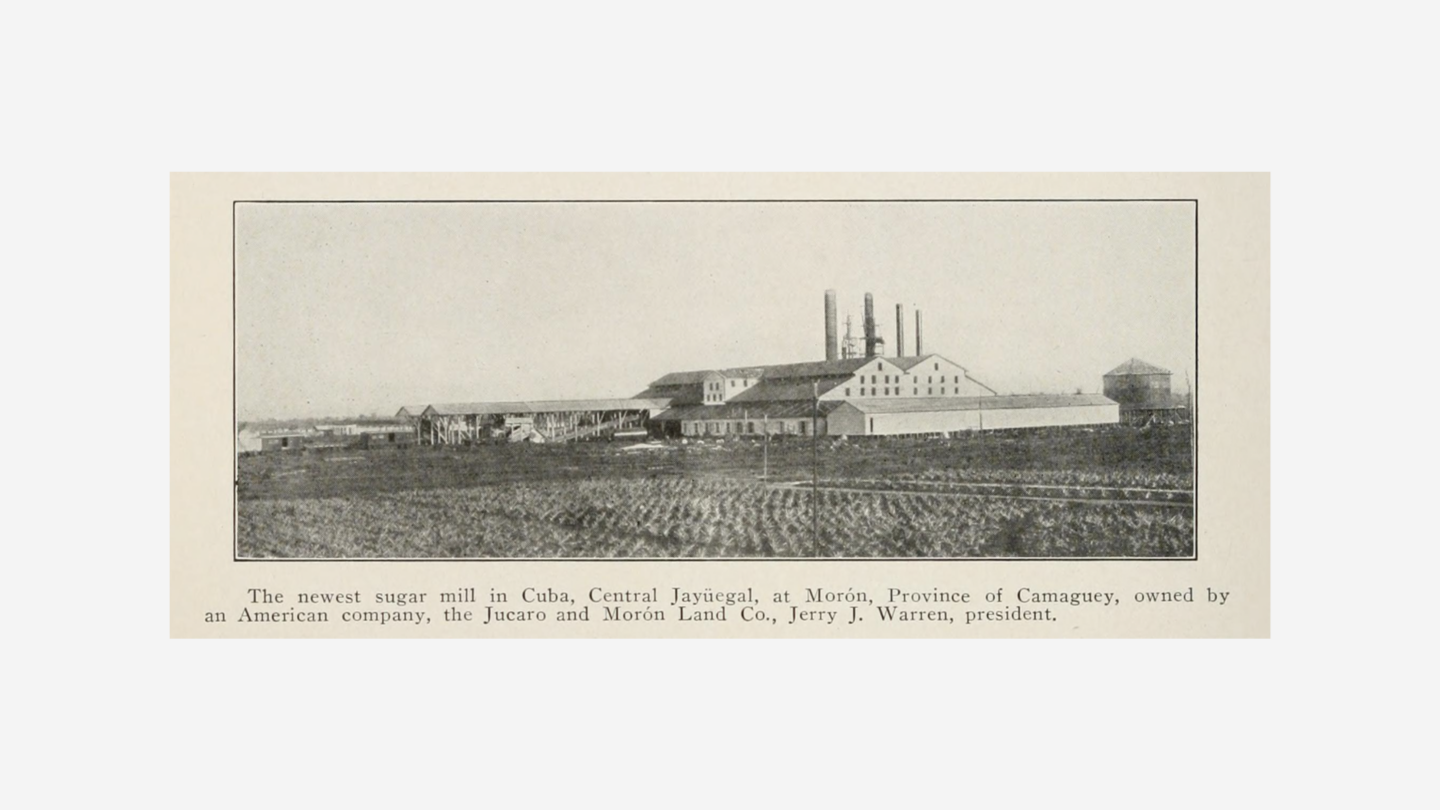

Within two years of the site opening, the foundry received a lucrative multi-million-dollar contract from the New Jersey-based Júcaro and Morón Sugar and Land Company to build a sugar factory in Cuba. After the conclusion of the then-recent Spanish-American War, Cuba was dominated by U.S. business, and the Pratt brothers saw an opportunity to get involved. At the time, The Atlanta Constitution hailed the deal as “one of the most important contracts of the kind ever made by an Atlanta firm”.

It was at this point that the Hurts became interested in the business. The Hurts were a powerful and wealthy family best known for their patriarch, Joel Hurt, an early Atlanta developer. Hurt was involved in many of the prominent industries that dominated Georgia at the turn of the century, including electric power, banking, convict labor (until the 1908 ban of the practice), and real estate. Real estate consumed most of his time, as two of his companies, the East Atlanta Land Company and Kirkwood Land Company, developed Inman Park and Druid Hills into the neighborhoods they are today. The latter company is also where his son, engineer George Fletcher Hurt, sold 27 acres of unused farmland in Kirkwood to the Pratts to build their foundry, and now wanted to be more involved.

In December 1908, George Hurt bought the engineering business from N.P. Pratt Laboratory for $290,000 and brought the prospect to his father’s attention. On January 6th, 1909, Joel Hurt and the East Atlanta Land Company agreed to invest in the newly named Pratt Engineering and Machinery Company for $500,000 worth of stock. A copy of the contract documenting the transaction is in Atlanta History Center’s archives.

Nathaniel and George Pratt initially stayed on to manage the technical side as President and Vice-President, respectively, with George Hurt serving as Treasurer. Joel Hurt remained as an investor, but slowly took on a more prominent role and would later serve as the company’s president.

From there, the company experienced success. Pratt Engineering and Machinery Company continued their efforts to build factories in Latin America, including another sugar mill in Cuba, which was reported at the time as “the largest sugar concern in the world”. At its peak, Pratt Engineering had offices in New York City, Chicago, and Havana, Cuba.

The company also ran into legal trouble. In 1909, Kirkwood resident Emma Trotti sued the company for $2,500 after the factory dumped refuse into a brook that ran through her property. When the company’s attorney did not show up for the suit, the sum was awarded to Mrs. Trotti. She later consented to a second trial to allow for the company to present a defense but upped the damages. She was awarded an additional $500. The Pratt company appealed this decision all the way to the Supreme Court of Georgia, who sided with Trotti.

In 1917, the United States entered World War I, and the Pratt Company came with it. In addition to contracts to produce shells for the Allied powers acquired before US entry into the war, the company designed factories for the Canadian and US governments. In June 1918, possibly the first event ever hosted on the site occurred when a rally was held to promote Kirkwood War Savings Stamps.

The company focused on its government contracts until the end of the war, when journalists for The Atlanta Journal captured the sentiment on Armistice Day.

Employees of the big industrial plants who reported to work early in the morning were among the first to start celebrating. At least two big war plants, the Pratt Engineering works and the American Machine and Manufacturing Company, closed for the day and turned loose their workers to mingle with the downtown crowds.

(The Atlanta Journal, November 11th 1918)

“Government Sues for $283,500”, seeking to recover funds after Pratt Engineering files for bankruptcy and accuses the company of using those funds to cover other expenses, July 7th, 1922. The World News via Newspapers.com

Despite these opportunities, within a few years of the end of the war the company declared bankruptcy. The company later operated under different names, often with the same basic leadership, until the land was sold to the Pullman Company in 1926.

Atlanta Pullman Shops

Then-Governor of Georgia Eugene Talmadge and his wife using a Pullman Sleeping Car to attend President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 3rd inauguration, January 1941. Kenneth Rogers Photographs, Kenan Research Center.

What was the Pullman Company?

In 1926, the Pullman Company acquired the land to build their sixth and last sleeping car overhaul facility. Founded in 1862 by George Pullman, by the 1920s Pullman was one of the most powerful companies in American industry.

A Pullman sleeping car provided overnight accommodation for long train rides. Over time, the sleeping car model evolved from simple open section berths to additional accommodations, such as private compartments and drawing rooms for wealthier clients.

Pullman Porter at Union Station, Chicago, Illinois. January, 1943. Jack Delano Photographs, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Today, Pullman is best known for the porters that staffed these cars. Each Pullman sleeping car was staffed by one porter who handled their luggage, made up berths, and assisted passengers to their compartments. Passengers were encouraged to refer to this porter as “George” after the company’s founder, regardless of whether that was the porter’s actual name. Also on the most deluxe trains were the Pullman maids, who worked on Pullman cars to assist women and child passengers and juggled additional responsibilities like childcare and upkeep.

Pullman porters and maids were largely Black. This made the Pullman Company one of the largest employers of Black workers in the United States, and some individuals were able to use these positions to build a comfortable middle-class life for themselves and their families. Porters were paid relatively low wages and relied on tips to maintain a steady income. With seniority, Pullman porters and maids could bid on the most lucrative runs, staffing sleeping cars on trains which traveled between large business centers.

These employees often faced discrimination during their tenure. For maids, sexual harassment from male passengers was common. In addition, beyond seniority, there was no potential for advancement within the organization after a certain point, since conductor jobs were exclusively reserved for white employees.

To try to address these and other issues, a group of Pullman porters organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids in 1925, one of the first African American led labor unions. Its leader, A. Phillip Randolph, fought for and won a collective bargaining agreement in 1937. That union, and Randolph’s leadership, became an important forerunner of the American Civil Rights Movement, with Randolph becoming the organizer of both the 1941 March on Washington and, with Martin Luther King Jr. and Bayard Rustin, one of the principal organizers of the subsequent 1963 March on Washington.

Opening the Atlanta Pullman Shops

By the 1890s, Pullman built most railroad sleeping cars, leased them to the railroads, staffed them with their personnel, and maintained them when needed. When tourism in the Southeast began to increase in the early 1920s, Pullman sought a more central location in the Southeast so their cars in need of major repair did not need to go all the way to facilities in Delaware or Missouri. As often happens when a key rail location in the South is needed, Atlanta was a natural fit.

In the January 1927 edition of Atlanta’s The City Builder, columnist Paul Hinde promoted the new shop as a major win for the city, as Pullman would be turning the site into a state-of-the-art overhaul facility on the site that would employ “seven hundred to a thousand men and women”. Among those developments included complete first aid facilities, a graduate nurse on the clock during working hours, and a complete restaurant on site “where the noon-hour meal can be conveniently secured”. The shop opened officially that August, with F.H. Geiger appointed as its first manager.

Once opened, the shop handled heavy repair for the sleeping cars. As The Pullman Company’s Pullman News advertised it:

Sometimes, cars will be rebuilt from the ground up, more often they receive a thorough overhaul. In an overhaul job, everything in the car gets a going over and the car is repainted inside and out. Greater passenger comfort is the aim of the shop program.

(Pullman News, January 1953 edition)

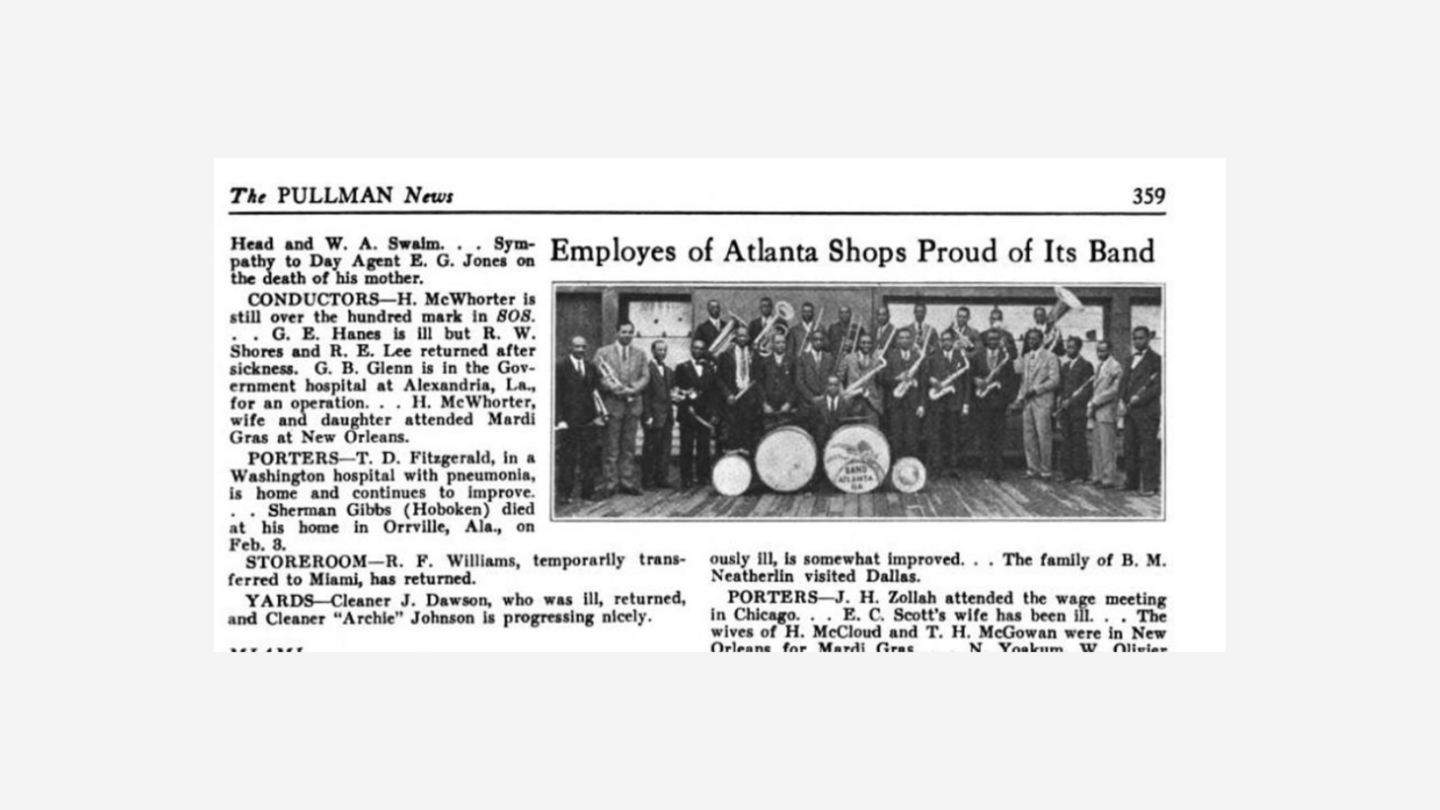

The staff of the shop included electricians, painters, typesetters (for an on-site printing press for company publications), upholsterers, and others responsible for making old cars look brand new.

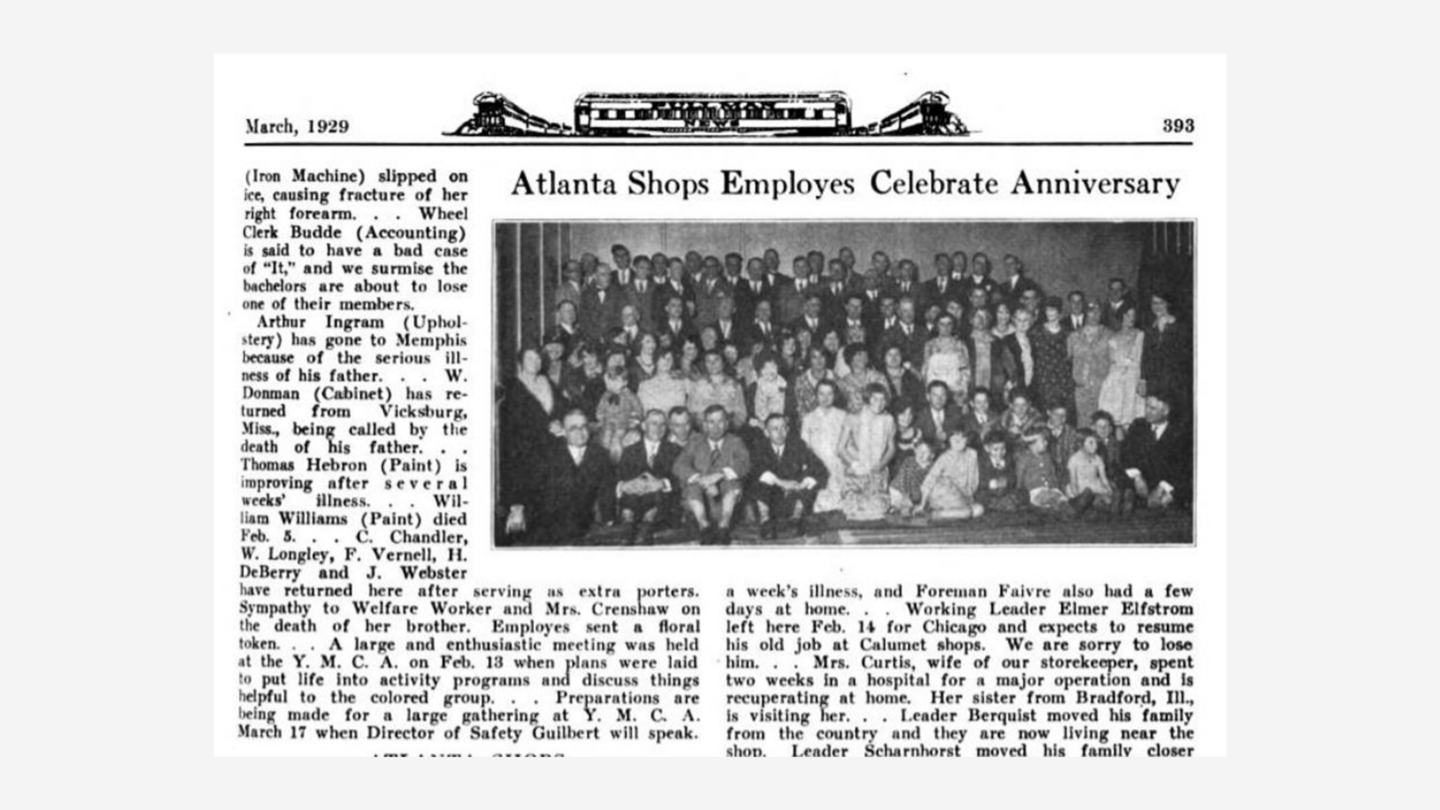

The Atlanta Pullman Shops employed Black workers who worked side by side with white employees, but segregation was enforced in other ways. In addition to segregated amenities, most of the higher paying jobs would go to white employees often with family connections resulting in departments often being divided along racial lines.

Most of the repair shops had an official social club and other outside of office activities that would be regularly shared in the Pullman Company’s newsletter, but in Atlanta these activities were segregated. Official social club events were usually hosted at segregated institutions.

The Pullman Shops continued to operate in Atlanta for the next 28 years. In that time, the shop won the Annual Safety Contest for Shop in the Railroad Employees National Safety Contest five times and had nine accident-free years.

Modern Day Site

Pullman Yards, courtesy Atomic Entertainment

Following World War II, the Pullman Company faced increasingly hard times. The federal government broke up the company on antitrust grounds in 1948. Passenger rail became less popular with the traveling public, especially as Federal investment in commercial aviation and superhighways was on the rise. As the railroads reduced the number of passenger trains, fewer Pullman sleeping cars were needed.

Pullman closed its Atlanta Shops in March 1954. In their February 1954 announcement, Pullman stated that the closure was due to a decrease in demand for luxury passenger cars, though they left their 5 other major repair shops open around the nation. For the next several decades the site operated as other railroad-centered businesses, such as Southern Iron and Equipment Company and Evans Railcar.

In 1990, the Georgia Building Authority purchased the site and utilized it to maintain locomotives and passenger cars for the New Georgia Railroad, a state-run tourist train that operated from Stone Mountain to the Zero Mile Post in Atlanta, but by 1997 the project had been shut down. From then, the lot was closed to the public.

In 2017 Atomic Entertainment, a film production company, bought the site from the state of Georgia. It soon became featured in several major motion pictures as the film industry came to Atlanta. Franchises such as The Hunger Games, Fast and Furious, and Bad Boys took advantage of the site’s industrial look to tell their stories, and major film and television productions still use the site to this day.

Starting in 2019, Atomic Entertainment began to use the site as an entertainment district renamed Pullman Yards. The buildings that once housed factory equipment are now event spaces. This includes the “drinks hall” AlcoHall with individual drink vendors, located in building one onsite. During the Pratt era it was the floor of the factory; during the Pullman era it was the upholstery shop.

Party with the Past: Pullman Yards will be hosted on Wednesday, May 15th, from 6:30–9:30 pm. We will get a chance to use the site’s new role as an event space to learn about the old roles it has held throughout our city’s history. We hope you will join us.