2/7 After Reconstruction

Retrenchment

By 1870, white Southern Democrats regained control of the Georgia legislature, effectively ending Reconstruction in the state.

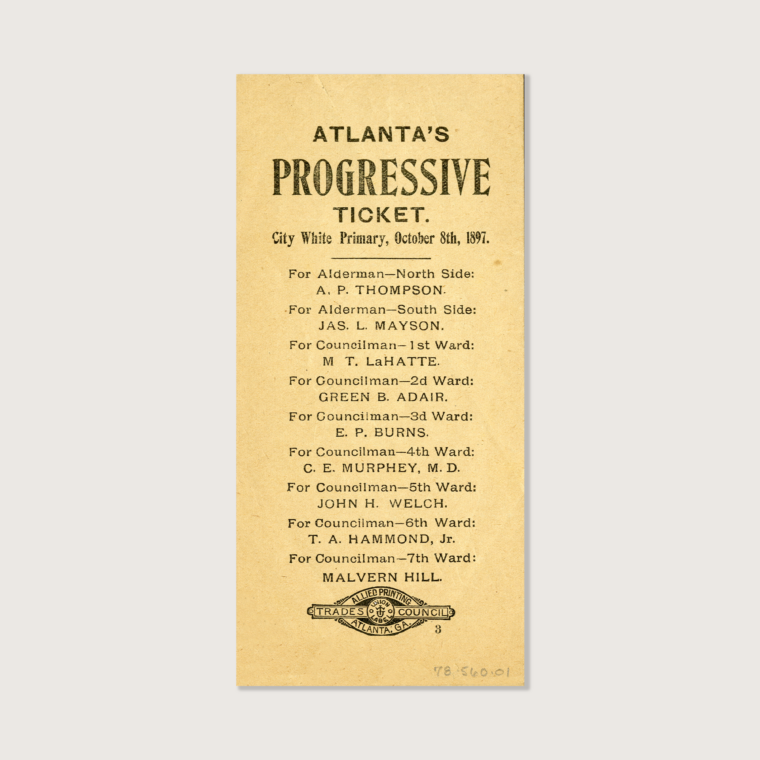

Over the next four decades, Black citizens were deprived of the right to vote beginning with the institution of the poll tax in 1877 by the Georgia Legislature. By 1900, only one out of 10 eligible Black persons remained on the voter rolls.

That same year, the state Democratic Party instituted the white primary barring Black voters from participation. In 1908, the state instituted literacy tests, property qualifications, and the grandfather clause, which exempted white people from two of those restrictions if they were descended from a veteran—essentially requiring a Confederate veteran.

During this period, white legislators at the state and local level passed laws that created an enduring system of racial segregation. Known broadly as Jim Crow laws, this system reinforced the second-class status of citizenship for the Black community. African Americans suffered continuous indignities by the way they were depicted in publications, popular songs, jokes, and cartoons.

Though Black Georgians experienced little political progress under Jim Crow, many did achieve a measure of economic success. While some Black farmers made the hurdle from tenant to landowner in rural Georgia, most Black economic development occurred in urban areas, where a small, but important, class of Black professionals emerged.

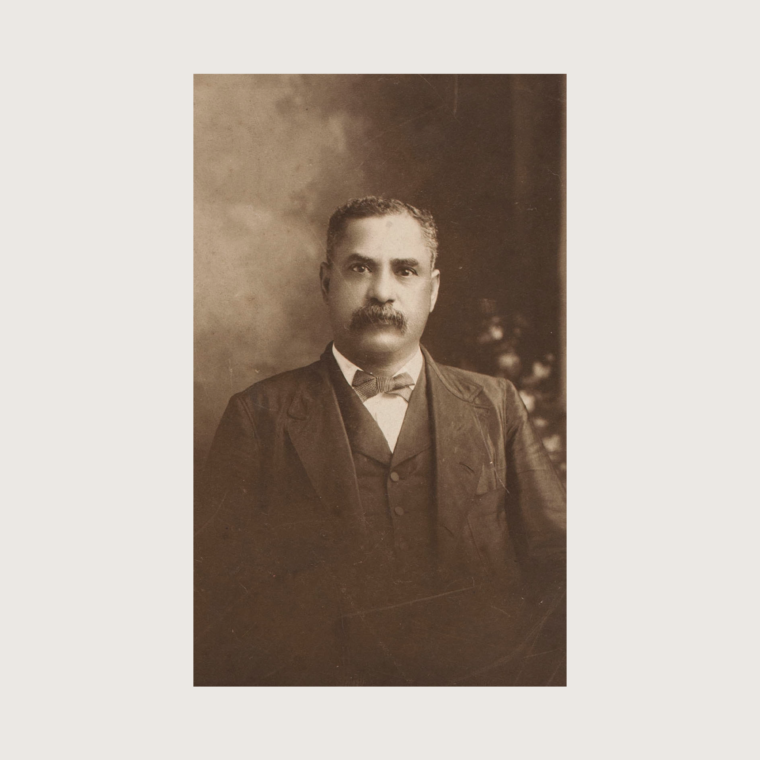

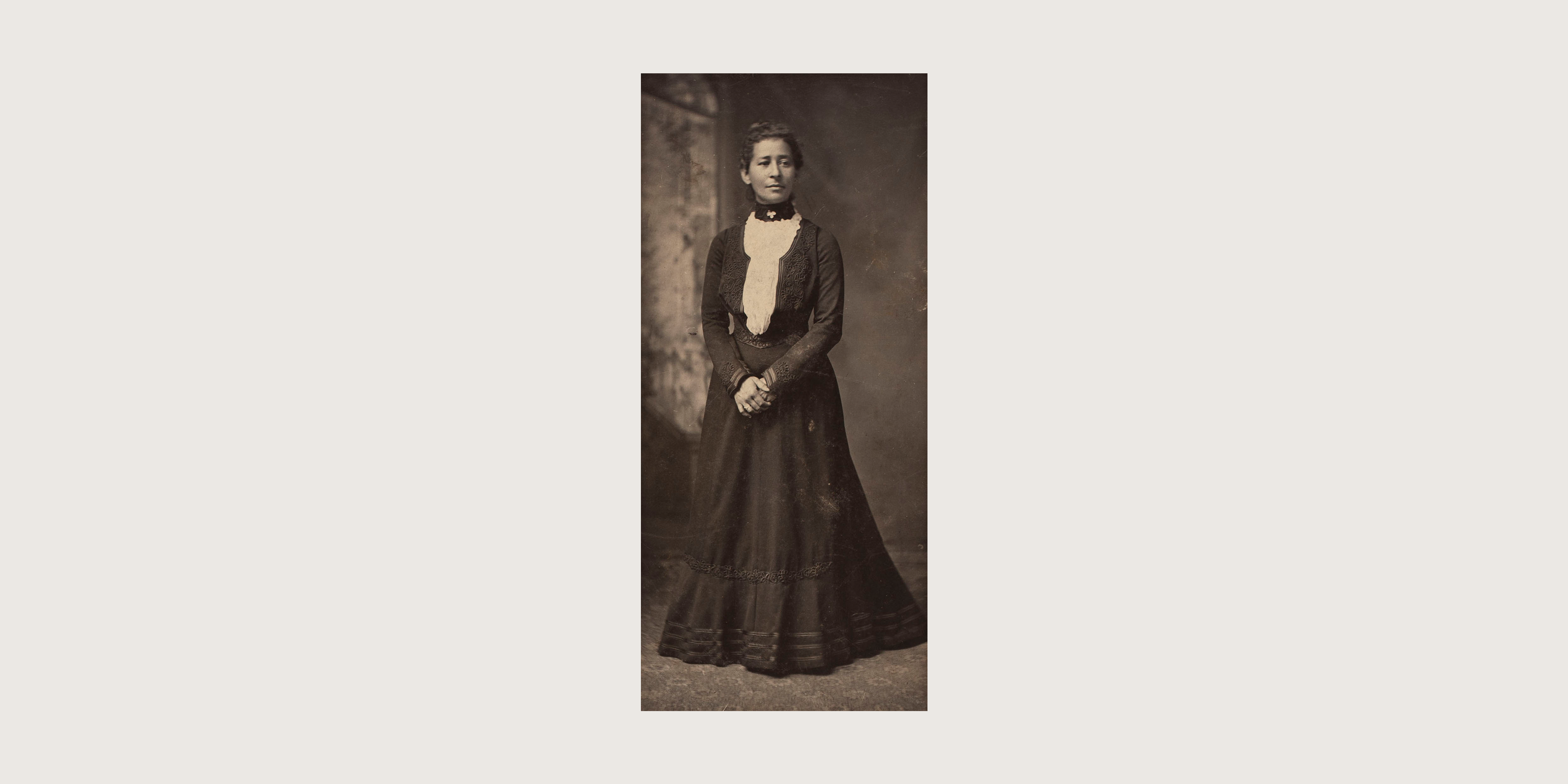

Header Image: African American Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

“We have no objection to your having a democratic primary, but when you have city elections where no politics are involved … we should be recognized. We are all equally interested in good government. In my little residence on Fort Street, I enjoy the fresh air just the same as the richest man on Peachtree Street. Therefore, I think we should be treated as if we were citizens and taxpayers of the great government, not as slaves.”

Convict Lease System

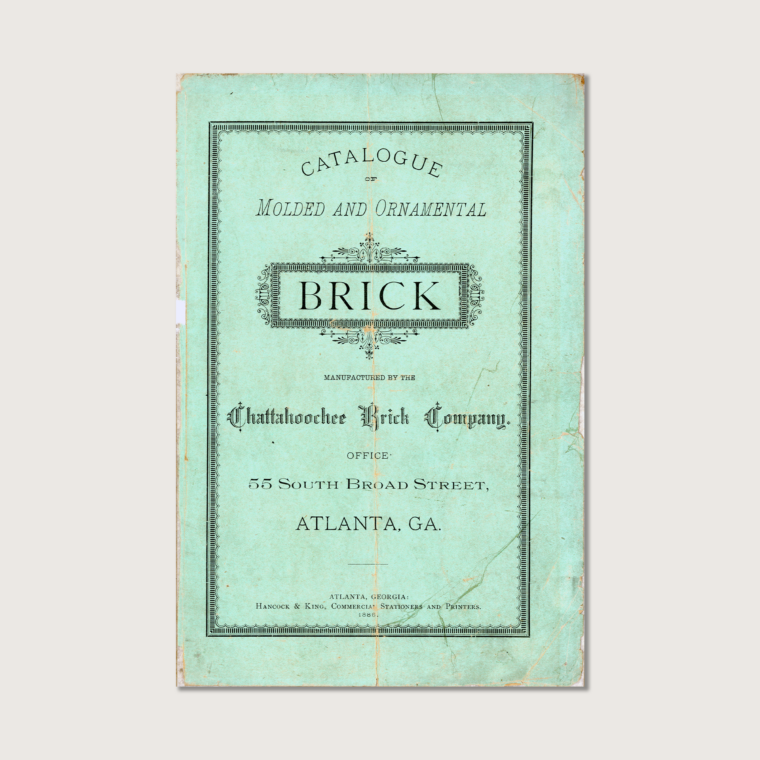

In addition to political exclusion and Jim Crow segregation, the Black population in Atlanta and throughout the South were subject to a system of debt servitude in which laborers are bound in “slavery by another name” to work to pay off their debts.

Beginning in the 1870s in states across the South, a system of convict labor developed wherein corporations, justices of the peace, judges, and sheriffs imprisoned an unknown number of Black individuals for petty and often non-existent crimes and confined them in labor camps.

In the wake of the passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that abolished enslavement, Southern lawmakers remade the legal code of their states to criminalize ordinary activities. For example, several Southern states made it illegal for a Black man to change employers without permission.

Often tried without due process, hundreds of thousands of men and women were pushed into forced labor. Taking advantage of the text of the 13th Amendment that specifically allowed involuntary servitude as a punishment for “duly convicted” criminals, Southern lawmakers created a system of industrial slavery that lasted until the 1940s.

Black Professionals

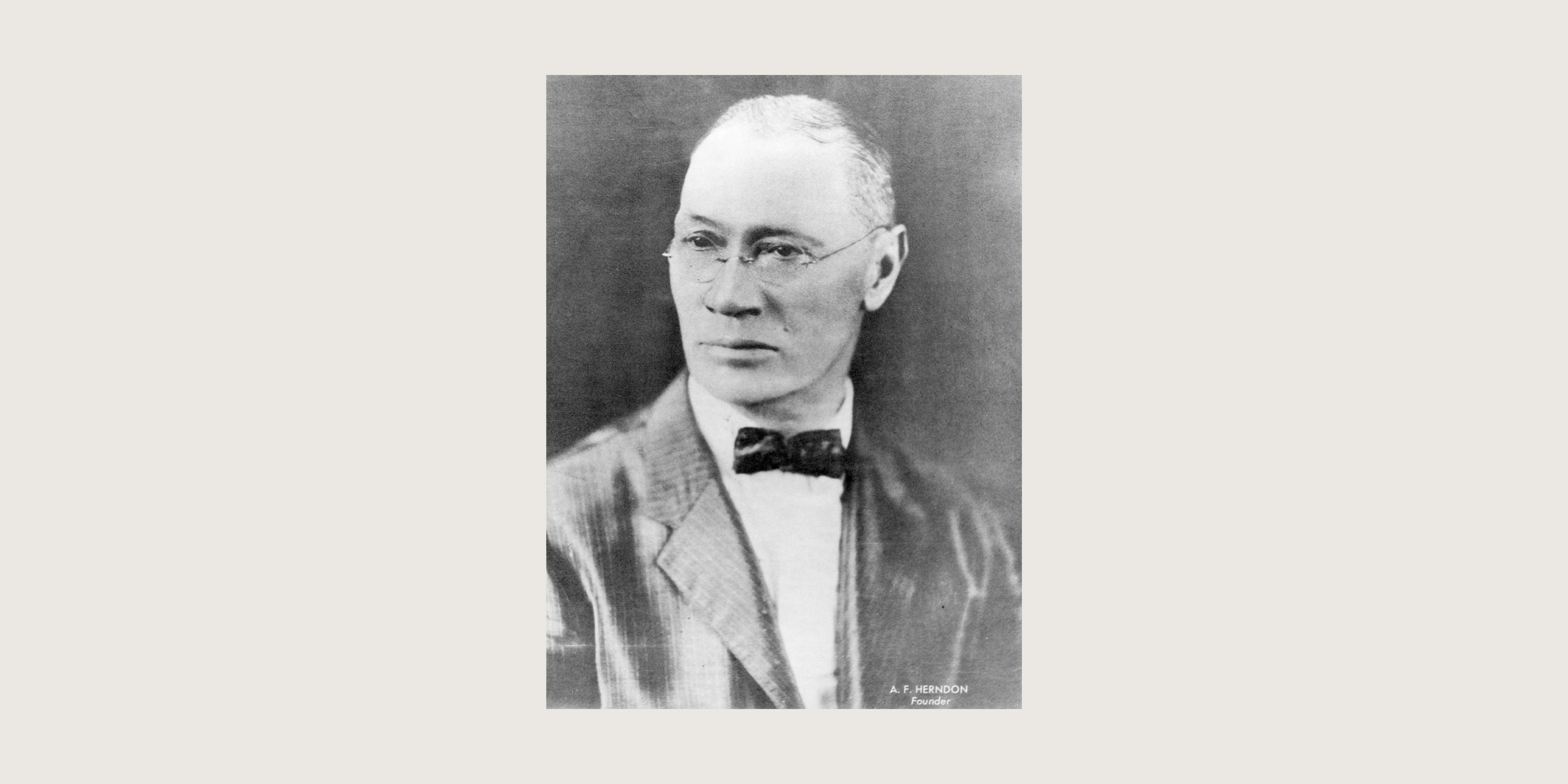

In spite of voter suppression and Jim Crow laws, Atlanta Black residents, many of whom had been born enslaved, made significant progress in promoting prosperity and economic development for the city’s Black community. African Americans established businesses, formed financial organizations, and made capital available for real estate investment and other endeavors.

The growing professional class also included small business operators, civil servants, ministers, and educators. These established the upper echelon in the African American community in the late 19th century.

Their economic success was based largely on a surging Black population in Atlanta that grew from approximately 9,000 in 1880 to 35,000 by 1900. The increasing Black population and the rise of the Black professional class in Atlanta created racial fear in the white population. Stoked by the use of such anxiety as a political issue and accompanying sensationalist newspaper coverage, those fears culminated in the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906.

Atlanta Race Massacre

White Atlanta’s impulse to suppress Black economic power and political participation—which had been ongoing for 40 years—hit a violent peak in the Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906.

Throughout that year, former Atlanta Journal publisher and gubernatorial candidate Hoke Smith raised fears of Black political domination and openly called for lynching Black people. Such alarmism led to widespread violence as mobs of white men attacked and killed approximately 25 African Americans over three days. Black residents fought back, and community leaders emerged from the violence to spearhead the ongoing fight for justice.