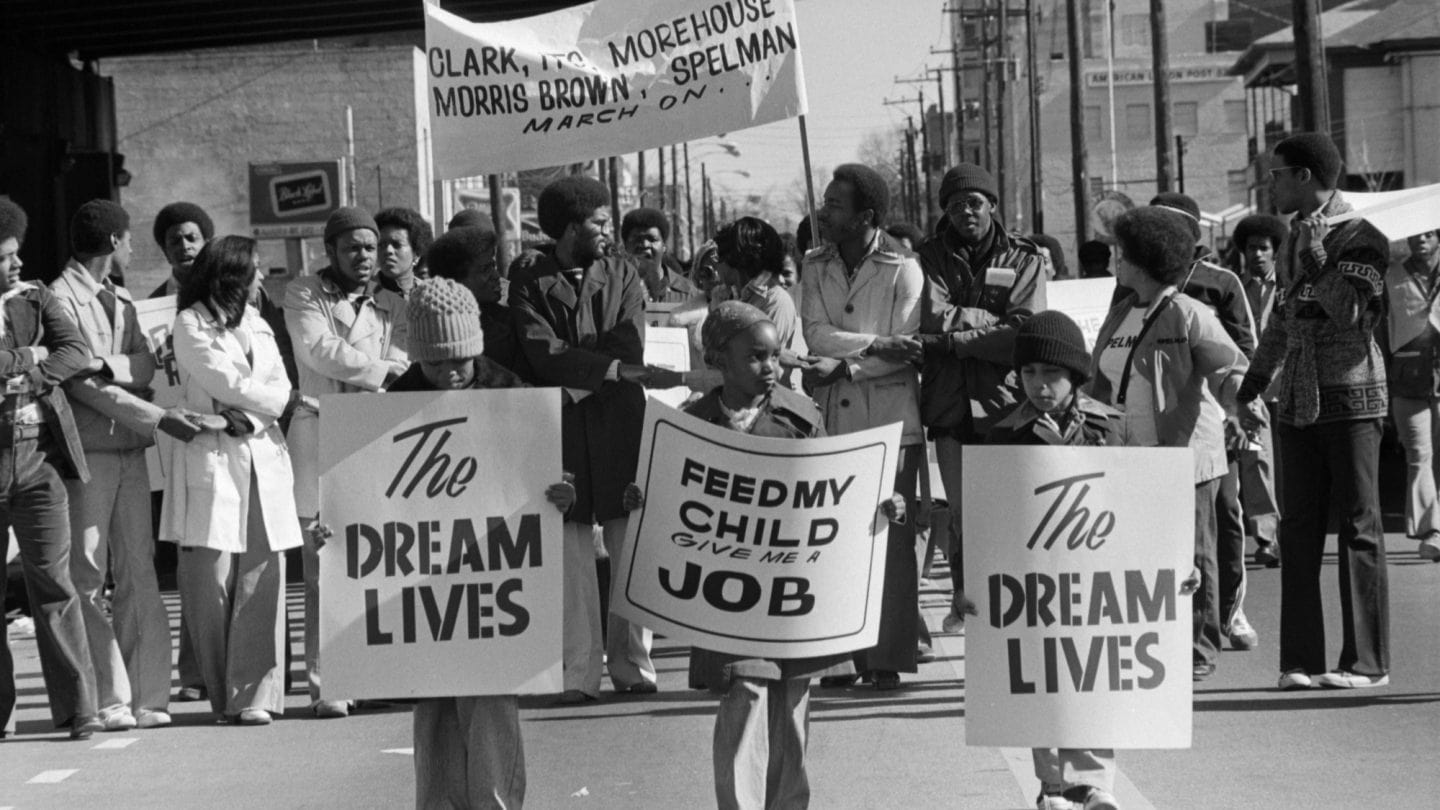

A procession on Auburn Avenue commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 47th birthday.

On the third Monday in January, people across the nation come together in the spirit of civic responsibility and volunteerism to honor the legacy of Atlanta’s most well-known civil rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. While we celebrate unity on this day each year, the path to the holiday’s establishment was fraught with challenges.

Shortly after King’s assassination in 1968, his widow, activist Coretta Scott King, joined forces with members of Congress and popular entertainers to press for a national holiday. Federal legislation designating the third Monday in January as a legal holiday did not pass until fifteen years later. Even then, several states refused to acknowledge its significance. The first year the U.S. officially observed the holiday was in 1986.

For the past 52 years, visitors from across the Unites States have traveled to Atlanta, King’s hometown, to honor the legacy of his work. We invite you to look back at how we arrived at this moment in history as we at Atlanta History Center prepare for our own Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration. Enjoy free admission on January 20, 2020, for a day of immersive performances, programs, and community conversations.

Coretta Scott King flanked by unidentified organized labor leaders, announcing plans for a January 15th birthday observance for her late husband.

Celebrating Dr. King In Atlanta

Four days after King’s assassination in 1968, Congressman John Conyers Jr. (D-MI) introduced federal legislation that would establish recognition of King’s birthday —January 15th—as a federal holiday. The proposal, which he reintroduced year after year, while strongly supported by the Congressional Black Caucus, garnered little support from most of Conyers’s fellow members of Congress and did not make it out of committee for many years. It also did not have presidential support for much of that time.

Some members of Congress opposed the creation of a Dr. Martin Luther King Day from the perspective that it was a logistical challenge. They argued that creating a new federal holiday that honored someone who did not serve as president would create an unsustainable precedent. It also would be expensive to pay workers and create a loss of productivity. Many also were simply opposed to the idea that King was a hero at all. They continued to resist the values and outcomes of the Civil Rights Movement and disparaged the character of the man himself.

Though King is widely embraced as an American icon now, at the time of his death, King was a polarizing figure in American politics. Oral histories and memoirs record two distinct responses when news of his death was shared on national television: everyone in the space breaking down in tears, or everyone in their shared space breaking out into applause. Opinions of him were rarely ambivalent—he was either beloved or viewed as a public enemy. Some news outlets painted King and members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (which King led since its founding in 1957) as “subversive” and “radical,” while many in the growing Black Power Movement feared that he was not radical enough.

Nonetheless, the groundswell of support for a national holiday continued to slowly grow. To combat public misconception and to ensure her late husband’s legacy, Coretta Scott King organized commemorative programs in Atlanta every year on her late husband’s birthday.

On January 15, 1969—less than a year after King’s assassination and what would have been his 40th birthday—a suite of memorial celebrations took place across Atlanta. Organized by Coretta Scott King and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center, the events were attended by thousands of visitors.

During the commemoration in 1969, Harry Belafonte presided over morning prayer service at Ebenezer Baptist Church behind the pulpit from which King and his father both delivered sermons. Speakers included Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, Representative John Conyers, and Rosa Parks, among others. Amidst the celebrations, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Center in Atlanta called for nationwide commemorations and began advocating for a national holiday.

Stevie Wonder and the Court of Public Opinion

Throughout the 1970s, Coretta Scott King, the King Center, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference played an increasingly important role in the creation of a national holiday. Their combined efforts influenced several states, including Illinois, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, to enact statewide King holidays beginning in 1973. King’s own home state of Georgia adopted the January observance in 1984.

In Atlanta, celebrations around King’s birthday grew every year. As part of the King Golden Anniversary Celebration in Atlanta, January 11-16, 1979, Stevie Wonder took the stage at Ebenezer Baptist Church alongside Coretta Scott King, Ambassador Andrew Young, and Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, and declared, “January fifteenth should be a holiday that we all want. If we cannot celebrate a man who dies for love, then how can we say we believe in it? It is up to me and you. We hold the keys to opening the door to a truth we have all known all the time.”

Wonder issued a call to action on the vinyl sleeve for Hotter than July. It reads, “Join us in the celebration of January 15 as a national holiday.”

Following his declaration at the Golden Anniversary Celebration, Stevie Wonder released Happy Birthday—a song calling for the establishment of an official holiday for King. Wonder dedicated his next album, Hotter Than July, to King and embarked on a nationwide tour. The song reinvigorated the public’s interest in a national holiday. On the heels of Wonder’s album, Coretta Scott King traveled to Washington in 1979 to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee and joint hearings of Congress to urge passage of a national King holiday bill. She presented Congress with a petition of over six million signatures collected during the Hotter Than July tour.

In the wake of Coretta Scott King’s testimony and the and the continuing outcry of Wonder’s fans, the House returned to the issue of a King holiday in 1983. They voted to establish the third Monday in January as a federal holiday in King’s honor beginning in 1986. After a lengthy debate in the senate, the bill arrived on President Ronald Reagan’s desk and he signed it two weeks later in October 1983.

Make history with us at our annual MLK Celebration!

Dream Big, Dream Often

We invite you to celebrate Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to honor its namesake, his peers, and those who fought to create a nationally-recognized holiday honoring King in January. On Monday, January 20, 2020 from 10:00am – 5:30pm, enjoy this special community day, featuring inspired performances, programs, and historical simulations that highlight contributions and stories of African Americans in Atlanta. Explore and be a part of the conversation. Admission is free.

Among this year’s highlights is a performance of Walking Through the Valley written by Addae Moon, Atlanta History Center’s Director of Museum Theatre. Set in 1963, a young activist is asked by the “powers that be” to alter the language in a speech he’s written for what will become an historic event. He envisions a conversation with four iconic freedom fighters in an effort to decide whether a compromise will best serve the greater good.

We hope to see you soon!