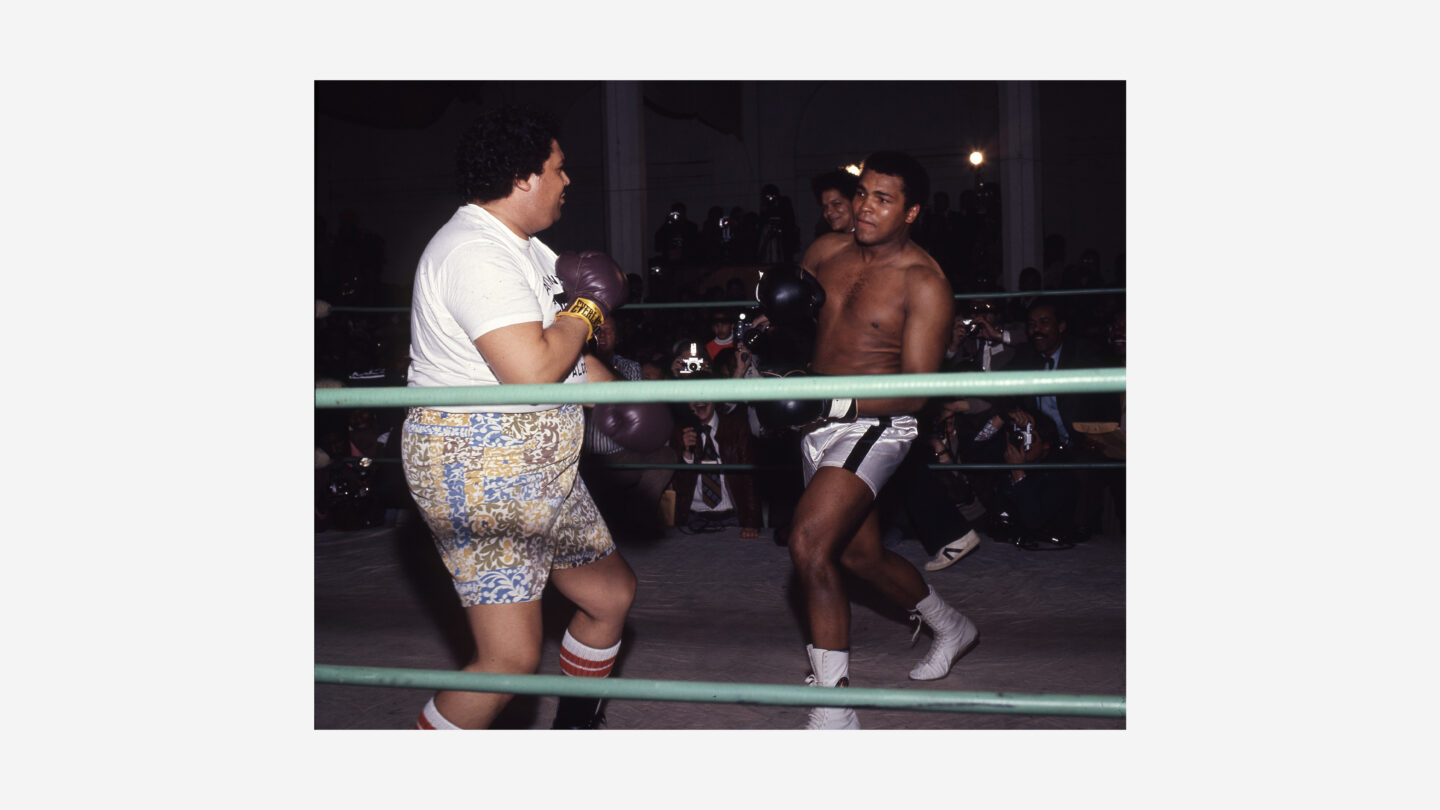

Muhammad Ali is shown in a boxing ring training for a fight with Jerry Quarry, wearing boxing shorts and with his hands in fists, in full length shots. Bettmann/UPI/Getty Images.

For some, Muhammad Ali’s defining connection to Atlanta is the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games where he famously lit the Olympic Cauldron to start the games.

For others, however, this was not the most important moment of Ali’s time in Atlanta, but the culmination of a decades-long relationship that proved to be beneficial to the city and boxer.

Ali’s relationship with Atlanta began with his 1970 comeback fight against Jerry Quarry, a fight that is often relegated to the footnotes of his legacy despite its crucial role in the growth of Atlanta and the rebirth of Ali’s boxing career.

After being drafted in 1966, Muhammad Ali refused to be inducted into the U.S. Armed Forces, citing a conscientious objection to the Vietnam War on religious grounds. In April 1967, days after defending his heavyweight title, the New York State Athletic Commission stripped Ali of his title and boxing license. The World Boxing Association also took away Ali’s boxing title.

In June 1967, Ali was tried and convicted of violating the United States Selective Service laws by refusing to be drafted. Though he was able to maintain his freedom as he appealed the court’s decision—an unusually harsh sentence of five years in a federal penitentiary and a $10,000 fine – Ali was unable to box for three years. Each state he approached to get a boxing license denied him one, effectively ending his career.

Georgia State Senator Leroy Johnson, foreground, and Atlanta Vice Mayor Maynard Jackson, seated next to Johnson, at a meeting between a coalition of Black officials and Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority in 1973. Boyd Lewis, photographer, VIS 101.464.015, Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

Ali’s career remained in doubt until 1970, when Senator Leroy Johnson, Georgia’s first Black state senator after Reconstruction, made it his mission to help Ali make a comeback.

Johnson discovered a loophole in Georgia’s boxing laws that could allow Ali back in the ring. Since the state had no boxing commission, the City of Atlanta could give Ali a license to box. After convincing Atlanta Mayor Sam Massell to allow Atlanta’s city athletic commission to give Ali a boxing license, Johnson went to see Governor Lester Maddox.

Johnson expected Maddox, a staunch segregationist, to attempt to prevent Ali from fighting in Georgia. However, with the help of powerful Black Atlantans, such as future mayors Maynard Jackson and Andrew Young, and Jesse Hill, the then CEO of Atlanta Life Insurance, Johnson was able to get Maddox’s approval.

After receiving permission for Ali to fight in Atlanta, Johnson and his team had to prove that Ali could still box after being sidelined for three years and, more importantly, draw a crowd.

They held an eight-round exhibition match in the Morehouse College gymnasium, September 2, 1970, during which Ali sparred against three opponents. The event was a success, completely packing the small arena and proving Ali could still fight, despite being a bit out of shape.

Alvin H. Darden III, Dean of Freshman Programs at Morehouse College, recalls Muhammad Ali’s exhibition fight at Morehouse when he was a student in 1970. Video courtesy of Daniel Cooley.

Following the exhibition, Ali sought to fight Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title, but was denied. Instead, he opted to fight Quarry, a popular, skilled white heavyweight boxer who had spoken out against Ali’s objection to the Vietnam War. The fight was held in Atlanta Municipal Auditorium, October 26, 1970.

A majority Black crowd excited to see Ali packed the 5,000-seat arena. During the match, Ali proved he had not lost any speed during his hiatus and dominated the bout, rarely letting Quarry get a hit. When one of Ali’s blows caused a large cut over Quarry’s left eye in the third round, officials ended the fight and declared Ali the winner by technical knockout.

Highlights from the Muhammad Ali versus Jerry Quarry fight at Atlanta Municipal Auditorium, October 26, 1970. Video courtesy of Youtube/ElTerribleProduction

While the fight was underwhelming, for many Atlantans the city’s time in the limelight was more than enough. The newly constructed Hyatt Regency hotel became a hotbed for Black wealth with local business owners mixing with Black celebrities from across the country, such as Diana Ross and Sidney Poitier.

Hyatt Regency hotel in downtown Atlanta. Floyd Jillson, photographer, VIS 71.195.06, Floyd Jillson Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

“[There] was a sense of pride seeing all these Black people with dignity coming together to support Muhammad Ali,” said Henrietta Antoinin, an assistant to Jesse Hill. Atlanta also received attention as a location for tourism and hosting more events and concerts, increasing local convention and hospitality businesses with future U.N. Ambassador Andrew Young remarking, “The fight made Atlanta a destination.”

For Ali, the Quarry fight marked the rebirth of his career. His New York boxing license was reinstated and soon after he fought his desired title match against Joe Frazier, the world heavyweight boxing champion at the time. Atlanta gave him a chance when no other city would.

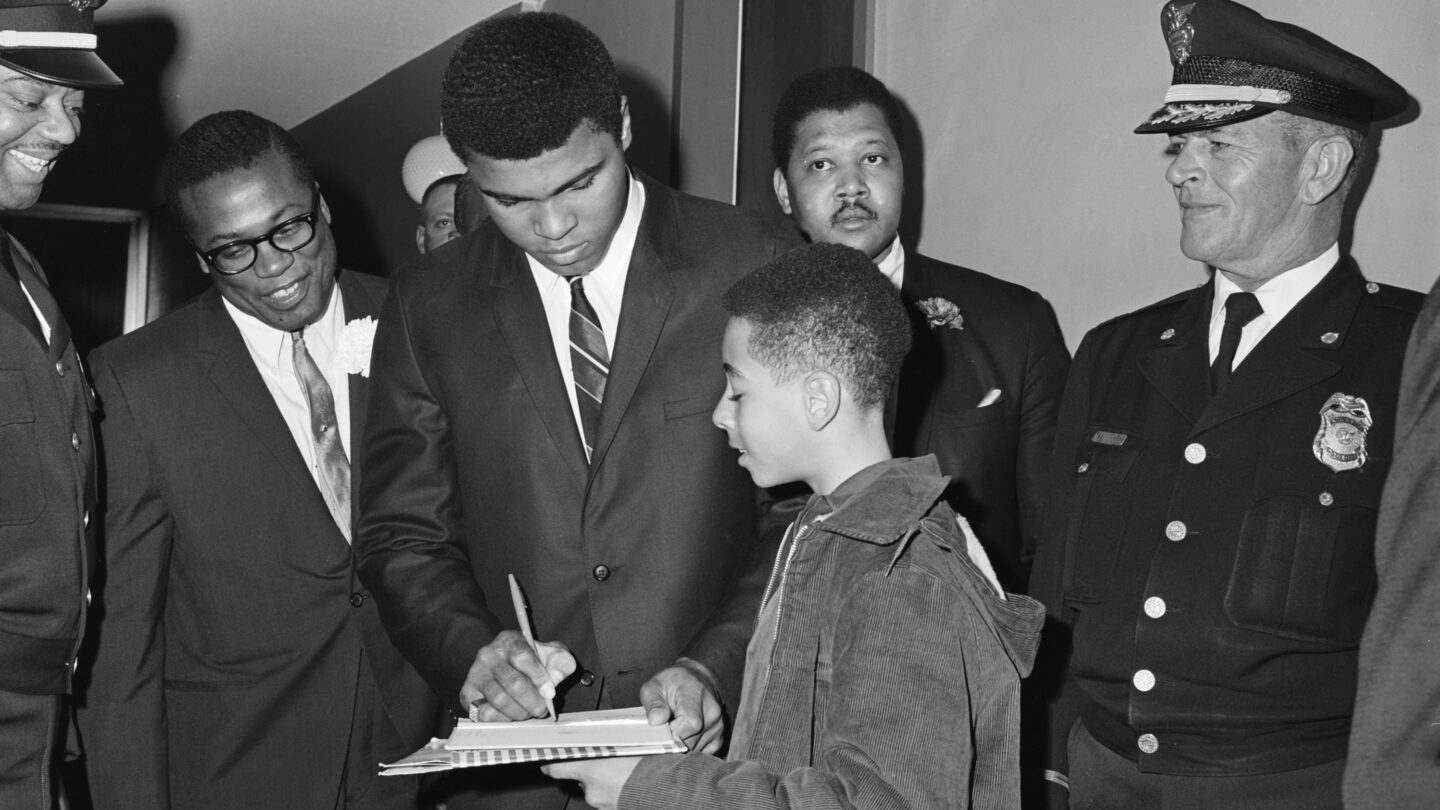

Boxer Muhammad Ali signs an autograph in Atlanta before his boxing match with Jerry Quarry. Joe McTyre, photographer, VIS 106.02.19, Joe McTyre Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center.

In the years following his comeback fight, Ali continued to interact with the Atlanta community, making appearances, speaking at local colleges, and interacting with the people he met at those events.

“He was a cult hero everywhere he went,” said Andrew Young. “He hugged and kissed all the women, signed autographs, and took pictures with all the children and anyone else who wanted a picture.”

Ali also became heavily involved in Atlanta’s political scene, remaining friends with Senator Johnson, Young, and others involved with the planning of his fight. He also supported Maynard Jackson’s mayoral campaigns through benefits and donations.

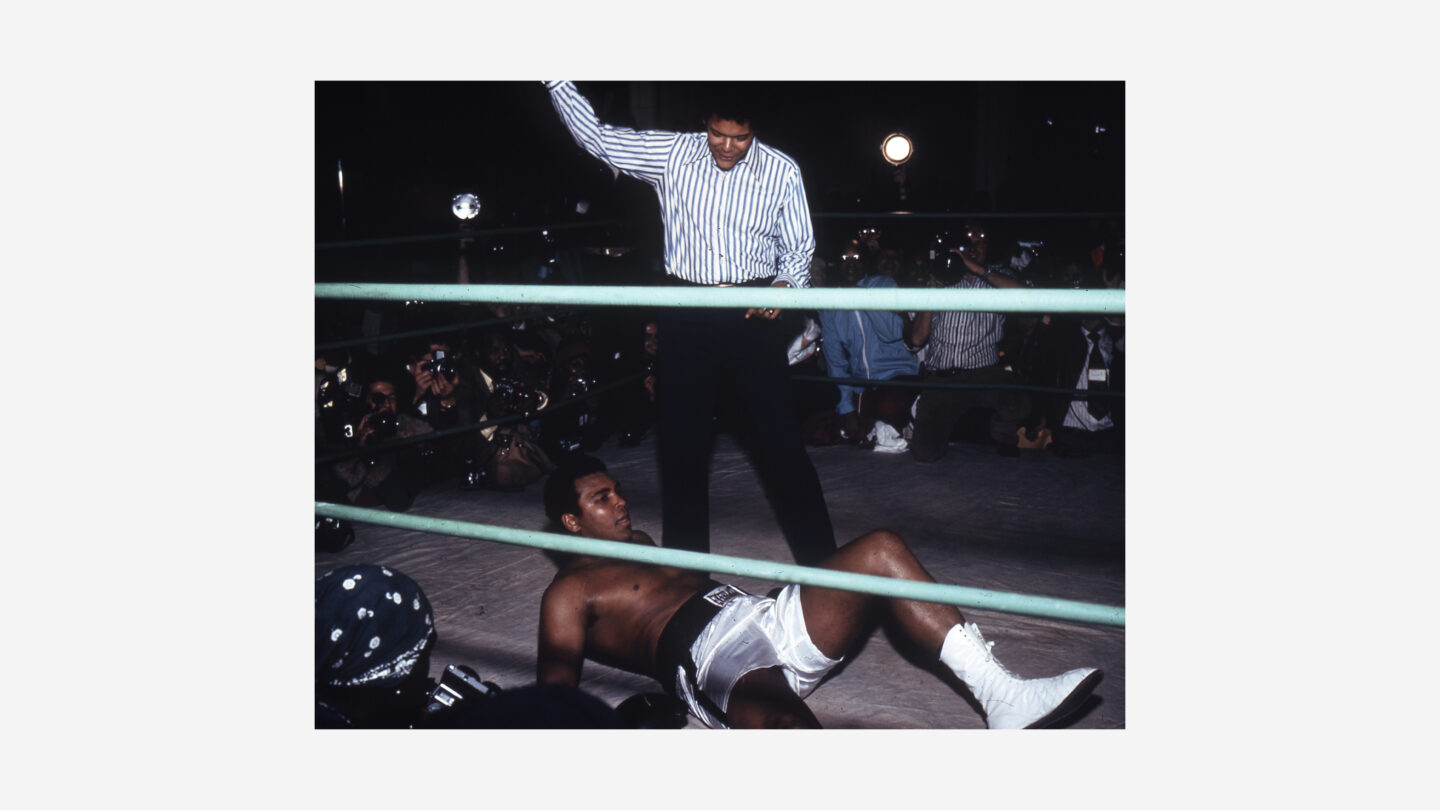

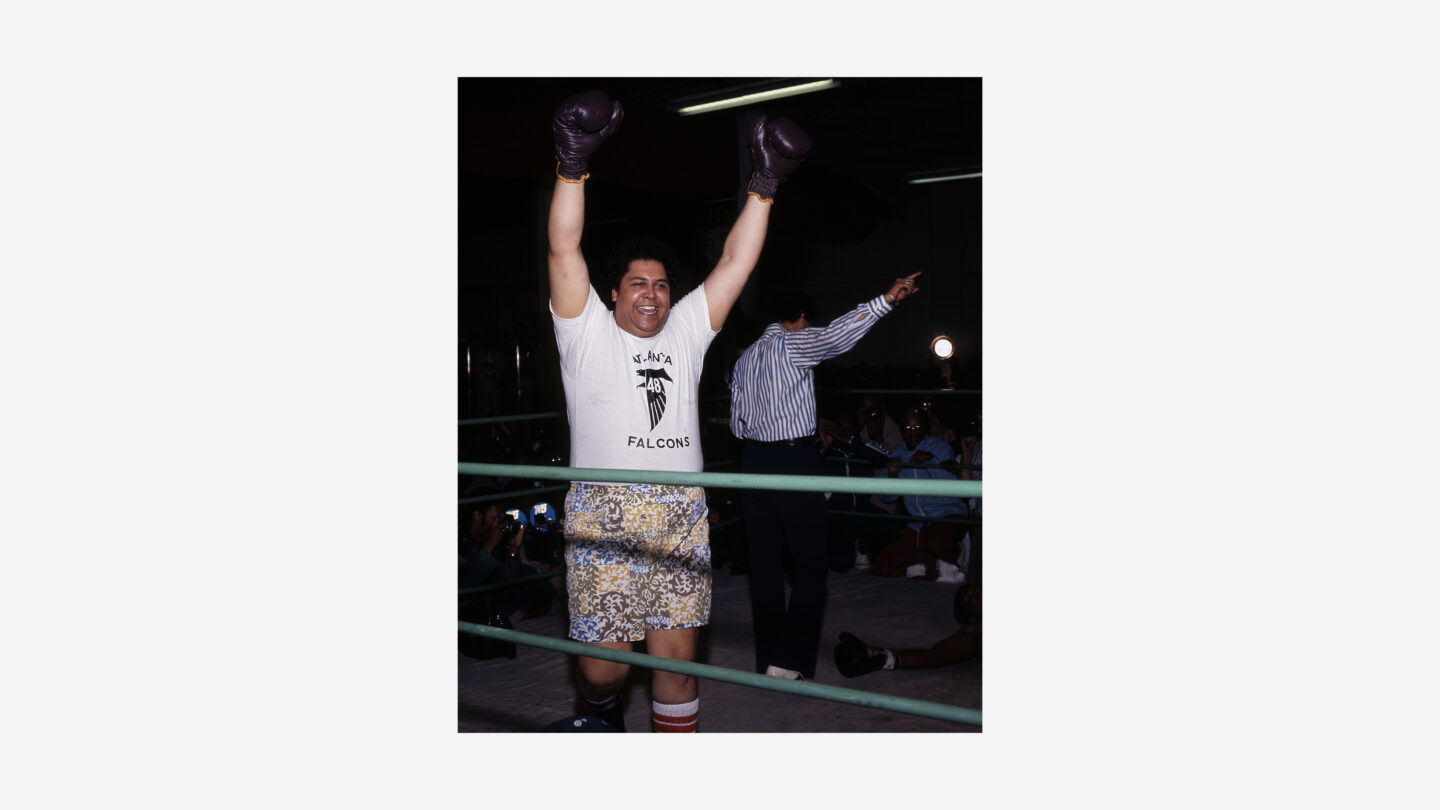

One of the most memorable displays of Ali’s support was his 1975 exhibition “fight” against Mayor Jackson, a charity event to raise money and awareness for local Black businesses. The three-round mock fight set the two massive personalities to collide with Ali demanding Jackson apologize for even dreaming about hitting him.

Civil rights leader Julian Bond officiated the match. Jackson came out in a bold pair of floral shorts and threw a few half-hearted punches, while Ali mercifully pulled his punches and took dives on those he received, so that the mayor won by TKO. The crowd loved the comedic affair, making the event a smashing success and further cementing Ali’s legacy in Atlanta.

Finally, after all he had done for Atlanta, Ambassador Young invited Muhammad Ali to light the Olympic flame for the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games held in Atlanta. Young and a few others planned his appearance in secrecy, which was executed to immense success.

Muhammad Ali lights the Olympic Cauldron at the Atlanta 1996 Olympic Games. Video courtesy of Youtube/SJT Sports

“[When I saw] it was Ali, I instantly said they got the right person,” said Evander Holyfield, heavyweight boxing champion. “He brought all these people together.”

As Ali emerged to light the flame in Centennial Olympic Stadium, the crowd erupted in applause for the Olympic gold medalist boxer, who stood as a strong figure despite his battle with Parkinson’s disease at the time.

Ali lighting the flame has now become part of the iconography of Atlanta, representing not only his athletic achievement, but his continued support and gratitude toward the City of Atlanta.