How did the world’s largest Confederate monument end up outside of Atlanta? What should be done, if anything, with it? With these questions in mind, Atlanta History Center explores the controversial history through online resources and an upcoming documentary.

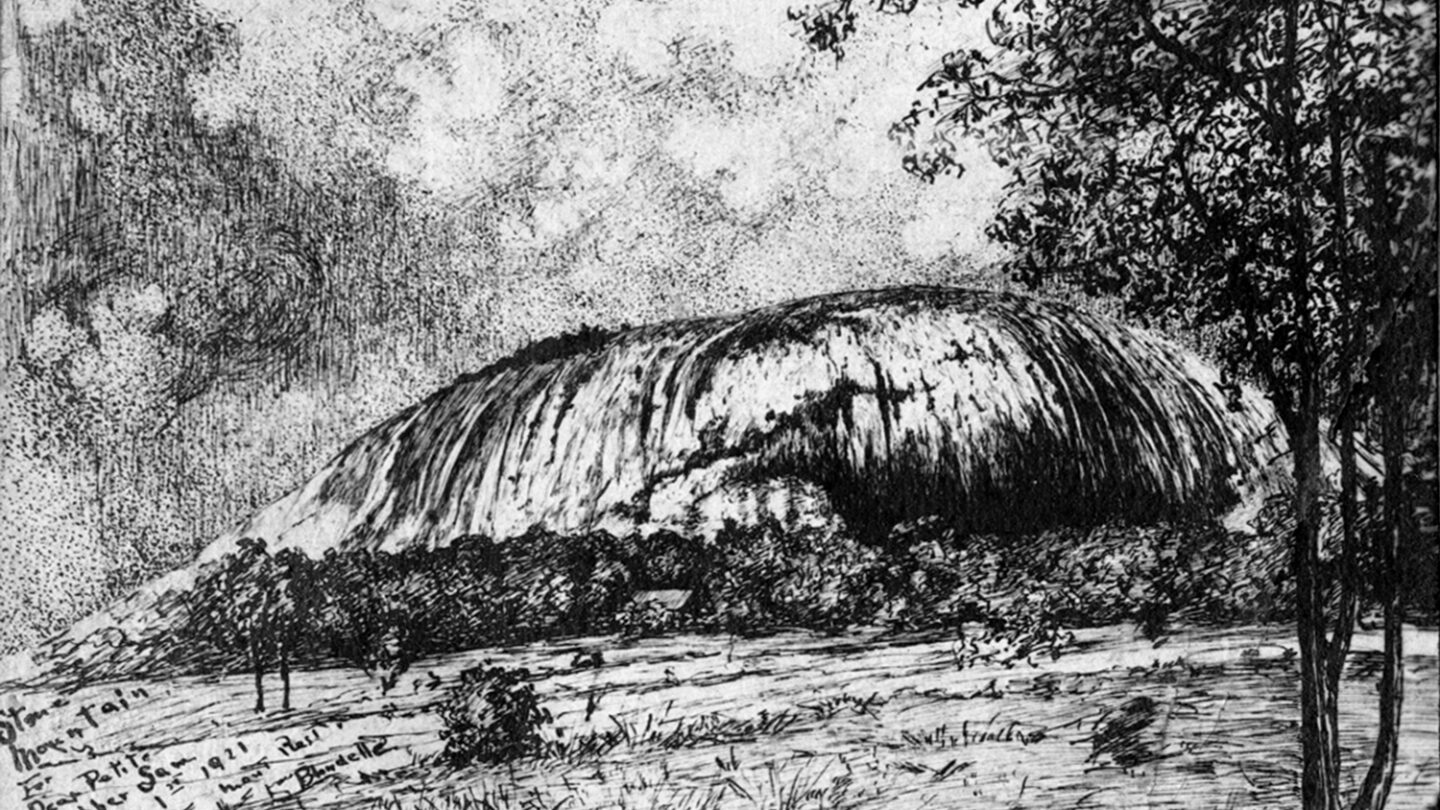

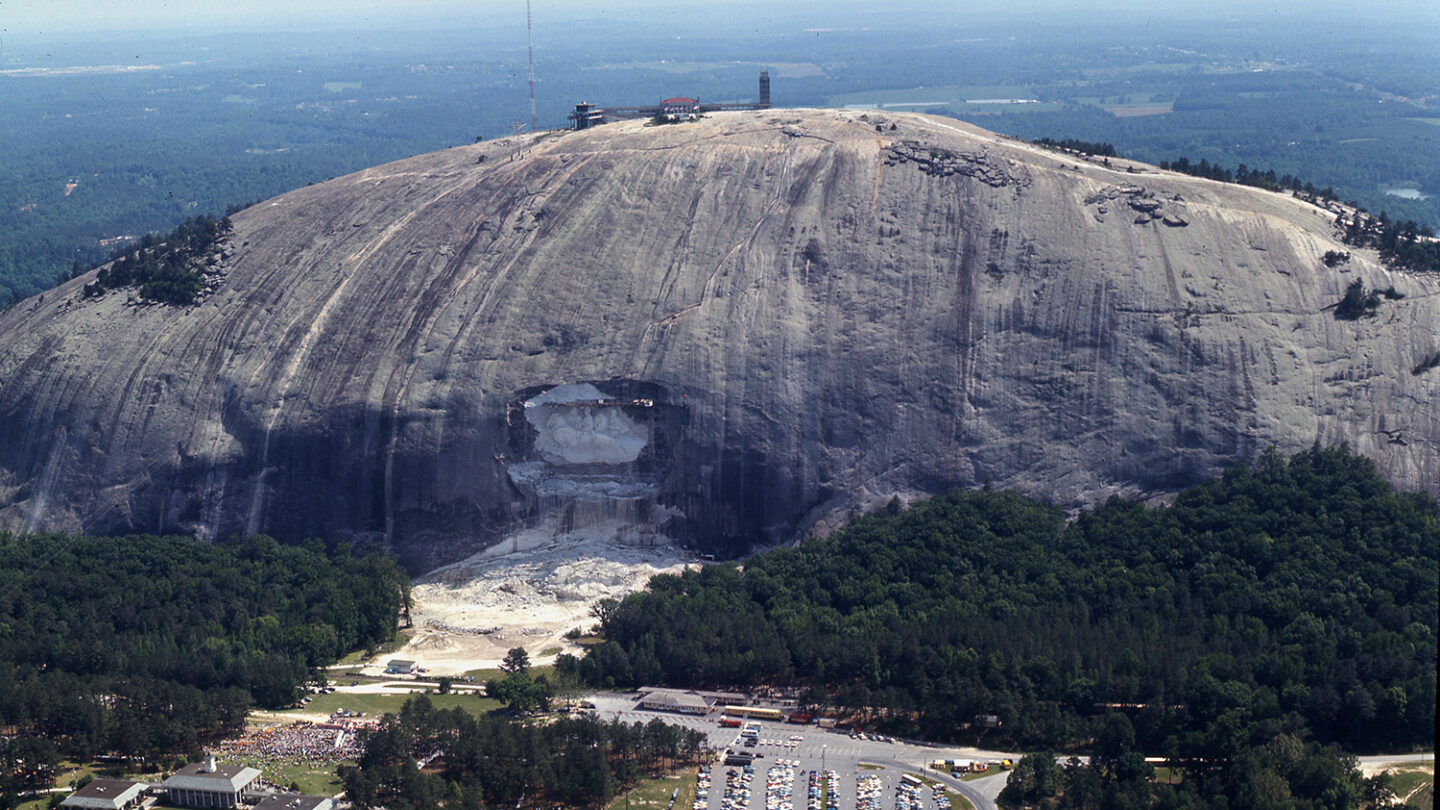

Stone Mountain—the world’s largest exposed granite outcrop—is a natural wonder turned Confederate monument. By Georgia state law, the entire park is designated as a memorial to the Confederacy. The effort to create a Confederate monument on Stone Mountain began in the 1910s. Yet, the monument was only completed in 1972. Spanning multiple efforts and more than 50 years, the carving’s history is full of twists and turns.

The original idea for a carving on the side of Stone Mountain was the idea of Helen Plane, a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and a Confederate widow, who advocated for a memorial featuring Robert E. Lee on the side of the granite mountain. She expressed admiration for the Ku Klux Klan after viewing the infamous film The Birth of a Nation and even mused that a formation of Klan members might be included in the carving along with the Confederate war heroes.

The Klan itself played a large role in this first effort to create the Confederate memorial at Stone Mountain. Inspired by The Birth of a Nation, Alabama native William J. Simmons held a ceremony atop Stone Mountain in 1915 to announce the re-founding of the Ku Klux Klan. The Venable family owned the mountain at the time and granted the Klan easements to use the mountain for its rituals.

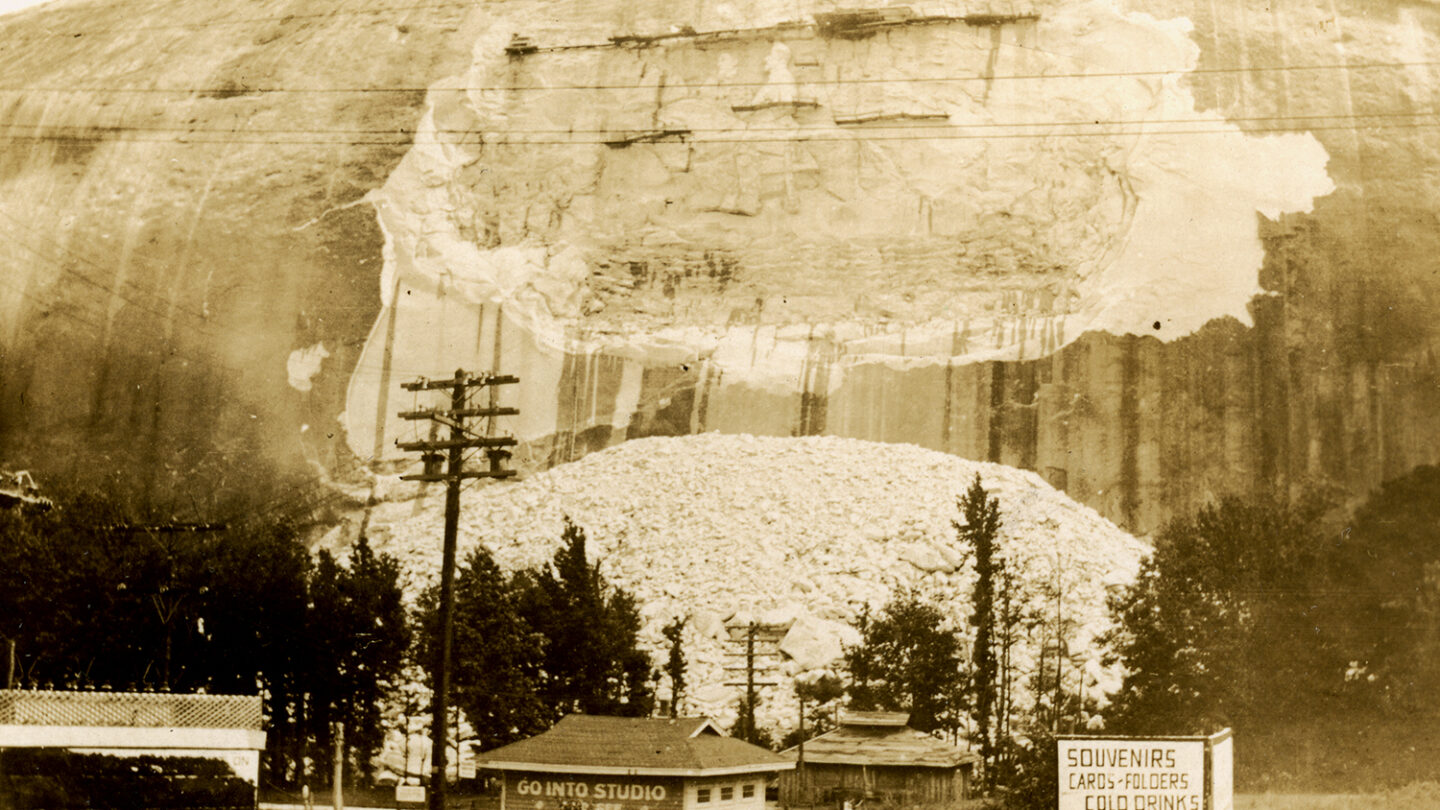

Shortly thereafter, the newly-formed Stone Mountain Confederate Memorial Association (SMCMA) organized an effort to carve a Confederate monument on the side of the mountain and realize Plane’s vision. Initially, the association hired carver Gutzon Borglum, who would go on to carve Mount Rushmore, but relations between Borglum and the association soured, partly due to intra-Klan disputes about new leadership that resulted in members of the SMCMA and Borglum being on opposite sides. After firing Borglum, the SMCMA blasted his work off the mountain. The association then hired American sculptor Augustus Lukeman, who managed to carve Robert E. Lee’s head and part of Lee’s torso into the mountain before funds ran out and the Great Depression set in, stalling the project.

At the time, the United Daughters of the Confederacy was a highly influential organization, and played a key role in reshaping popular memory of the Civil War. The Civil War is one of the most consequential events in American history. It began as an effort by Southern states to secede from the United States and establish a new slaveholding republic. For the Northern states, a fight to keep the United States intact eventually transformed into a referendum on the morality of enslaved labor.

After the war, former Confederates sought to rationalize their devastating loss—and in that process, developed Lost Cause ideology. This set of beliefs posit that the war was fought over anything but slavery, and instead places emphasis on state’s rights and tariffs as the supposed causes of the conflict, and the overwhelming military power of the Union army as the primary rationale for defeat. The United Daughters of the Confederacy eagerly advanced this view of the Civil War, choosing favorable history textbooks for schools, hosting Confederate memorial day ceremonies, and building scores of monuments across the South (and in some cases, the North.)

Though the beginnings of the monument came during the heyday of The Lost Cause in the 1910s and 1920s, it was not completed until after a campaign promise from gubernatorial candidate and segregationist Marvin Griffin restarted the effort in the 1950s. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education overturned the legal basis for segregation in public schools. Fifty-seven days later, Griffin pointed to the mountain at a campaign rally and promised to finish the carving as a salute to those who fought for the South’s “way of life,” a “polite” way of saying preserving segregation.

With the election of Marvin Griffin, Georgia’s state and local governments joined the “Massive Resistance” political movement, trying to deny Black Georgians the right to vote, fighting school integration, and doing their best to maintain the racial status quo of white supremacy. Griffin and state legislators changed the Georgia state flag in 1956 to add the Confederate battle flag design and purchased Stone Mountain in 1958 to build a Confederate memorial, fulfilling his campaign promise.

In the 1960s, as Black people and allies organized during the Civil Rights Movement, the carving was slowly completed. Martin Luther King Jr. had just been awarded his Nobel Peace Prize as workers finally finished carving “Stonewall” Jackson’s face in 1964. As Alabama state troopers beat future congressman John Lewis and his fellow protestors in Selma, Alabama, workers put the finishing touches on Jackson’s torso. In 1970, the carving was officially unveiled. Vice President Spiro Agnew spoke at the dedication—a snub to many white Southerners who felt that President Richard Nixon himself should have been there. Details were added to the carving until 1972.

The continued presence of the carving stands in stark contrast to the removal of the Confederate battle flag from the State of Georgia flag in 2001.

Pieces of legislation that made both possible were passed during Marvin Griffin’s four-year administration. Yet, more than two decades later the Stone Mountain carving remains effectively rededicated each day by state law as a Confederate memorial. In the years since, these laws have been reaffirmed and even strengthened. O.C.G.A. § 12-3-192.1 establishes the Stone Mountain Memorial Association as one to “maintain an appropriate and suitable memorial for the Confederacy,” while the more recent § 50-3-1 states: “the memorial to the heroes of the Confederate States of America graven upon the face of Stone Mountain shall never be altered, removed, concealed, or obscured in any fashion and shall be preserved and protected for all time as a tribute to the bravery and heroism of the citizens of this state who suffered and died in their cause.”

The history of the Stone Mountain memorial is one that is often unknown or misunderstood—understanding the origins and intention of the carving, as well as its meaning to our lives today, might be one way to have a constructive conversation about the future of the carving and the designation of Stone Mountain Park as a Confederate memorial.

Atlanta History Center explores the puzzle of the Stone Mountain carving, its history, and what’s at stake for our future in online resources under the Confederate Monument Interpretation Guide and in the documentary Stone Mountain, coming soon.

For a more detailed history and sources on the Stone Mountain carving, please read Atlanta History Center’s “A Condensed History of the Stone Mountain Carving”.