During the summer of 1996, Atlanta hosted the Centennial Olympic Games and the 10th Paralympic Games. People flocked to our city from around the globe to watch the world’s most talented athletes compete for the most coveted prizes in sports. We broke ground on new infrastructure, built arenas and sports facilities, and fundamentally altered Atlanta, transforming it into a host city.

But, how does a city get the Games in the first place? How did Atlanta, a newcomer to the global stage, insert itself into the company of Athens, Tokyo, London, Paris, Rome, and Los Angeles? It all started with a bid.

Atlanta ’84

The 1996 Games weren’t the first Olympic prize Atlanta had its eyes on. In the 1970s, Olympic handball player Dennis Berkholtz campaigned to convince city leaders to bid for the 1984 Games. His efforts made the news. Bumper stickers saying “Atlanta & Georgia Olympics 1984” were speckled around the city. Yet many considered the possibility doubtful. Mayor Maynard Jackson’s office commissioned a study of what a realistic bid would include: possible venues, sources of funding, and risks and benefits.

While the idea of distinguishing Atlanta as a host city was tempting, city leaders also recognized risks. Recent Olympic Games were rife with disaster. Massacre and political unrest overshadowed the Games in Mexico City (1968) and Munich (1972) and the Montreal Games (1976) financially devastated the city. These challenges were fresh in city leaders’ minds.

Atlanta was not the only city deterred. As the bidding process for the 1984 Games closed, Los Angeles remained the lone volunteer. This emboldened the organizers of the Los Angeles bid, who made changes to the standard model of Olympic planning. They planned for Games funded largely through the private sector, alleviating the risk to government budgets. This new model was—pardon the pun—a game-changer.

The 1984 Olympic Games turned a profit and cities across the world noticed.

Quest for an International City

In 1987, Atlanta resident Billy Payne revived Atlanta’s Olympic aspirations. Inspired by a successful fundraising campaign in his church, Payne was on the lookout for another passion project that would impact the city at large. The Olympic Games were the perfect opportunity. Working with influential associates, Payne got his idea in front of Mayor Andrew Young.

In the 1980s, the federal government reduced funding for U.S. cities and the 1984 Olympic Games helped solidify mega events as an investment opportunity. During his two terms, Mayor Young made international investment a top priority. That, coupled with a personal affection for the Olympic Games, helped override much of the skepticism. With the backing of business leaders and city government, the campaign became official.

Payne brought together a group, often called the “Atlanta Nine,” to initiate the process. The team was composed of skilled lawyers, real estate executives, business leaders, fundraisers, and event planners. The affluent, all-white group was hand-picked through professional networks rather than elected to represent the diverse population of Atlanta. The Nine, along with Mayor Young, navigated the politics, cost, and planning of the multi-step Olympic bid, expanding their team with each stage.

Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation staff members celebrate winning the United States Olympic Committee bid, Washington, D.C., April 30, 1988 (Conway Atlanta Photography) | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

First, they competed nationally against Nashville, San Francisco, and Minneapolis-St. Paul. Beating out Minneapolis-St. Paul in a 14-2 vote, Atlanta won the support of the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), now called the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee. Robert Helmick, President of the USOC, and many others considered a U.S. host city for the 1996 Games unlikely since the 1984 Games were so recent. However, those involved knew that the process of a bid, even a failed bid, would help Atlanta in its quest for “International City” status.

Selling Our City

Atlanta’s bid team, the Atlanta Organizing Committee (AOC), faced a monumental task. In order to host the Centennial Olympic Games, the AOC would have to convince the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to accept their candidacy as a relatively unknown mid-sized city. The competition was especially fierce given that 1996 marked the 100th anniversary of the modern Olympic Games and that Athens, Greece—home of the first modern Olympic Games—was one of the competitors.

Atlantans pose as they unpack AOC merchandise at a sporting event, Atlanta, circa 1990 (Unidentified AOC staff photographer) | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

For two years, the AOC team worked to generate buy-in from Atlanta’s residents and government to prove the city’s capability. Thousands of citizens purchased t-shirts, hats, water bottles, pins, and merchandise branded with the popular logo.

Members of the AOC visited dozens of IOC representatives in their home countries; decorated Atlanta with billboards and banners; hosted representatives in groups, promoting Atlanta’s civil rights history and visiting the King Center; planned large-scale sporting events to boost the city’s athletic resume; rode on MARTA, toured venues, and drove across the state to show off satellite sites, such as Savannah.

The AOC even commissioned a song for the city’s bid: “The World Has One Dream.”

Despite the unified vision of Atlanta presented by the AOC, there were local critics of the city’s bid. Most of the opposition was organized by Atlanta’s community support and anti-poverty organizations, as well as other grassroots initiatives. These voices were not as visible or united as in several other candidate cities, but those opposed to Atlanta’s Olympic ideas left a paper trail through distributed newsletters and pamphlets. Some Atlantans were skeptical of the city’s chance to win the bid and extensive media coverage came late in the bid process. As a result, opposition efforts gained little traction.

Excerpt from The Open Door Community’s Hospitality newsletter, “Keep the Olympics Out of Atlanta!,” John Barbour, August 1990 | 1996 Olympics Subject File – Olympic Bid in Atlanta, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

A Pitch for the Centennial

Keenly aware of their underdog status, Atlanta’s organizing committee put extra effort into the materials they prepared for the IOC. The official candidacy submission, often called a bid book, was a specially designed five-volume boxed set. The AOC also partnered with computer scientists at Georgia Tech to produce an interactive video presentation where the viewer flew through a virtual landscape of the city of Atlanta during the proposed Games. The innovative presentation was a feat of early computer-generated animation and companies at the forefront of animation, such as then-little-known PIXAR, were consulted during the planning process.

Atlanta’s Olympic campaign went into the final phase of selection on strong footing. Mayor Andrew Young’s international political connections drew support from IOC representatives in Africa and Asia. Their campaigning highlighted how the Games in Atlanta could align with the history of civil rights, rather than the Civil War and the American South’s history of enslavement. The high-tech nature of Atlanta’s bid positioned the city as a launch site for the future of the Olympic Games, rather than a backward glance.

Members of the AOC Dream Team stand next to protestors of Toronto’s bid on selection day, Tokyo, September 1990 (Unidentified AOC staff photographer) | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

The Selection

September 18, 1990, marked selection day. The Atlanta Organizing Committee, along with city and state leaders and a multi-racial coalition of young supporters, known as the Dream Team, headed to Tokyo for final presentations and election by the IOC. Atlanta was on the ballot with Athens, Greece; Belgrade, Yugoslavia; Manchester, England; Melbourne, Australia; and Toronto, Canada.

Competition was stiff. Athens was the sentimental choice, but some IOC members worried about Greece’s unsteady economy. Toronto gave Atlanta competition as another North American city and a previous Olympic bidder. But protesters of Toronto’s bid accompanied them to Tokyo and their prominent demonstrations impacted the IOC decision. Political unrest and ethnic conflicts were mounting in Belgrade. Manchester lacked sufficient facilities; Melbourne’s time zone posed broadcast concerns.

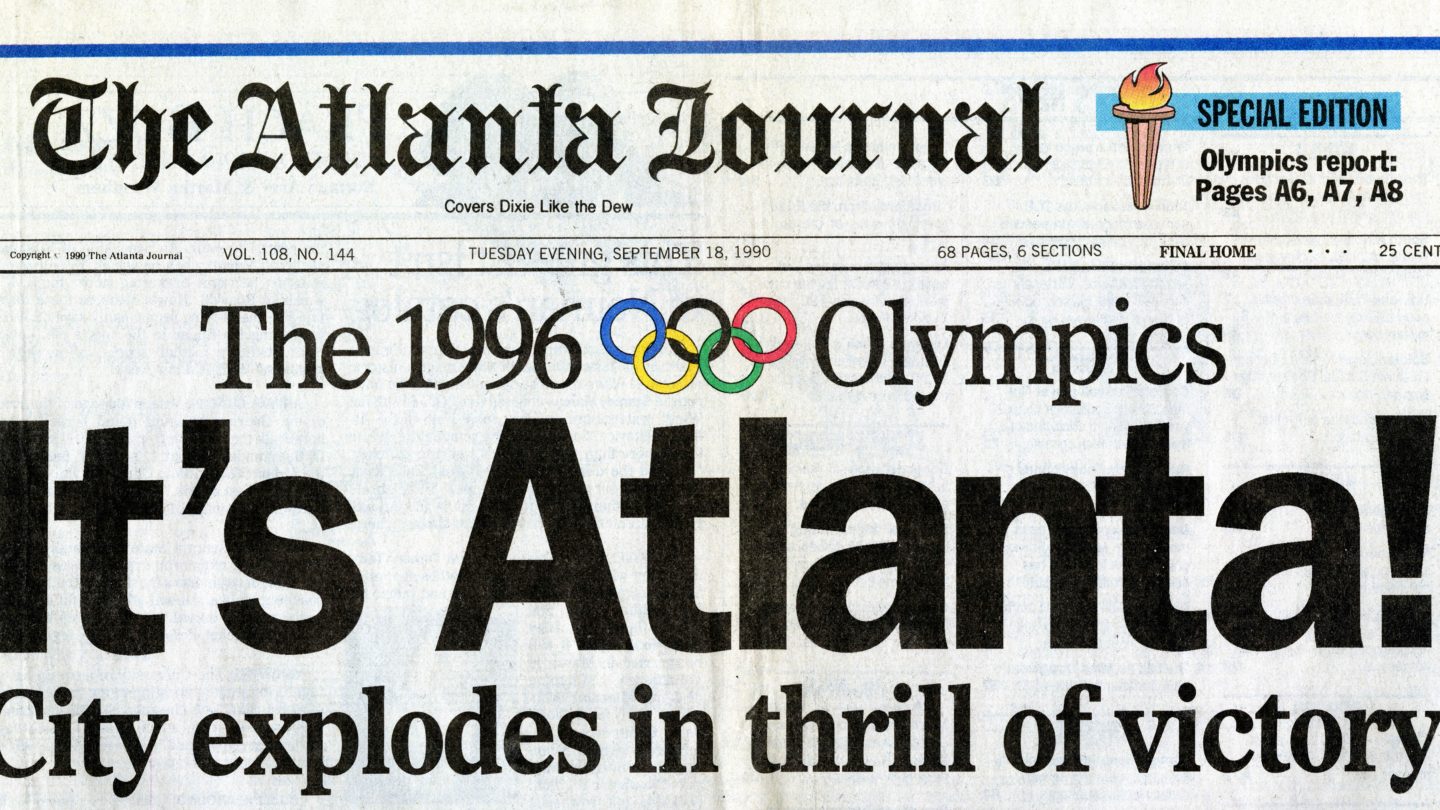

Atlanta’s strong campaign outweighed its status as a lesser-known city. IOC president Juan Antonio Samaranch announced the win in a moment still remembered by many Atlantans today. The announcement sparked celebration in Georgia and a famous front page from the Atlanta Journal.

“It’s Atlanta: City explodes in thrill of victory,” Tom Oder, Atlanta: The Atlanta Journal, September 18, 1990 | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

Private donations and some government support funded Atlanta’s bid process. But the price of the bid was a drop in the bucket to the cost of making the Games happen. Atlanta’s win meant the city had to quickly turn its attention to fulfilling the promise of the bid.

Alana Shepherd and Juan Antonio Samaranch shaking hands, circa 1996 (Unidentified photographer) | Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

A Separate Selection

The Paralympic movement gained steam after the first gathering of British World War II veterans at the 1960 Games in Rome. Bids for these games became increasingly formalized but remained separate from the Olympic process. While the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG) began preparations for the major event, the 1996 Paralympic Games did not have a host.

Atlanta’s Olympic predecessors, Seoul (1988) and Barcelona (1992), hosted both Olympic and Paralympic Games in the same city. This unity elevated the Paralympic movement and instituted a precedent for future hosts.

With Atlanta’s bidding process focused solely on the Olympic Games, ACOG was unprepared and reluctant to support preparations for an additional major event on top of the Olympic planning schedule. Local Paralympians and disability-rights advocates presented proposals to ACOG for funding and accommodations but secured only an agreement to share venues. Atlanta’s Shepherd Center became an early financial and operational supporter, helping to submit a successful bid to the International Paralympic Committee at the Winter Paralympic Games in Tignes, France, in 1992. These early supporters assembled the Atlanta Paralympic Organizing Committee to plan the world’s second largest sporting event of 1996 in Atlanta.

Still an afterthought to Olympic planning in the early 1990s, the separate nature of the Paralympic bid process in Atlanta helped push the international Olympic and Paralympic agencies to unify their planning efforts for the Games after 1996.

A Bid for Change

Looking back, the story of Atlanta’s bid for the 1996 Games shines light on why cities put their hat in the ring for major events. Like the Games themselves, the Olympic bidding process mirrors global economic and political changes as countries and cities vie to be worthy of host status. As a local history, it illuminates the tactics city leaders used to shape Atlanta’s image.

Since the 1996 Games, bidding processes have changed, adopting new approaches, reducing barriers and costs, and reacting to increasingly prevalent stories of public coalitions that object to the use of city resources for such events.

Atlanta’s 1996 bid may have been a one-time event for the city, but the results of the years-long process connect to citywide initiatives we see today. Whether it’s the Super Bowl or the NCAA Final Four, Atlanta has become a major destination for sporting events, new corporate headquarters, and national conventions. The city we inhabit still feels the effects of the 1996 Games.

Atlanta is always shaping itself for the next big pitch. What do you think it should be?

Additional resources.

Archival Material + Articles

- Chicago Tribune | About That Atlanta Bid for 1996 Games: It’s No Joke

- Georgia Amateur Athletic Foundation Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

- Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine, Vol. 73, No. 1 1996 | High Tech Games

- The New York Times Archives | Olympic Notebook; Maneuvers Start For Future Games

- Paralympic Games | Atlanta 1996 Paralympic Games

- Research Atlanta, Inc. Reports (Georgia State University Library) | The 1984 Summer Olympics in Atlanta: An Analysis

Scholarly Articles + Books

- Andrew S. Zimbalist | Circus Maximus: the economic gamble behind hosting the Olympics and the World Cup

- Geography Compass, journal | Olympic Cities: Regeneration, City Rebranding and Changing Urban Agendas

Major support of this exhibition has been generously provided by the James M. Cox Foundation, Marine and John Fentener van Vlissingen, Bank of America, The Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation, The Coca-Cola Company, Martha and Billy Payne, The UPS Foundation, Martie and Dennis Zakas, and The Rich Foundation.