Driving down a side neighborhood street called Slaton Drive in the Buckhead community of Atlanta, Georgia, one might notice a relatively small white house, cabin, and rows of planted crops peeking through the trees. Located across from townhomes and adjacent to some of the grandest homes in Atlanta, that seemingly out-of-place feature on the Buckhead landscape is Smith Farm.

Smith Farm was not always located in Buckhead—in fact, for over 100 years, it was located on what is now North Druid Hills Road in DeKalb County, east of Interstate-85, roughly 4 miles from its current location. The farm itself is many things: historical time machine to discussing Georgia before, during, and after the Civil War for people both enslaved and free, a story of historic preservation and women’s volunteer efforts, and most of all, an educational cornerstone of the Southeast’s largest history museum. Smith Farm is celebrating 50 years of being a site of public education on April 10, 2022. Atlanta in 1972 was a much different place than Atlanta today, but the farm nonetheless continues to serve an educational role. Its fate of preservation, though, was not always so certain.

View of Smith Family, including William Berry and Mary Ella Smith and their children, along with unidentified African American farm workers, ca. 1887

Who were the Smiths?

Before diving into the story of how Smith Farm ended up in Buckhead in the first place, the first question must be: who were the Smiths? Robert Hiram Smith, his wife Elizabeth Smith, and their children lived in the Smith farmhouse now located at Atlanta History Center. Prior to emancipation, between eleven and nineteen enslaved people also lived and worked on the farm at any one time, their labor integral to farming such a large plot of land. The enslaved people worked the 600-acre farm, producing cotton, butter, honey, and oats along with hogs, cattle and sheep. The Smiths would be considered equivalent to upper middle class for their time and location within the state.

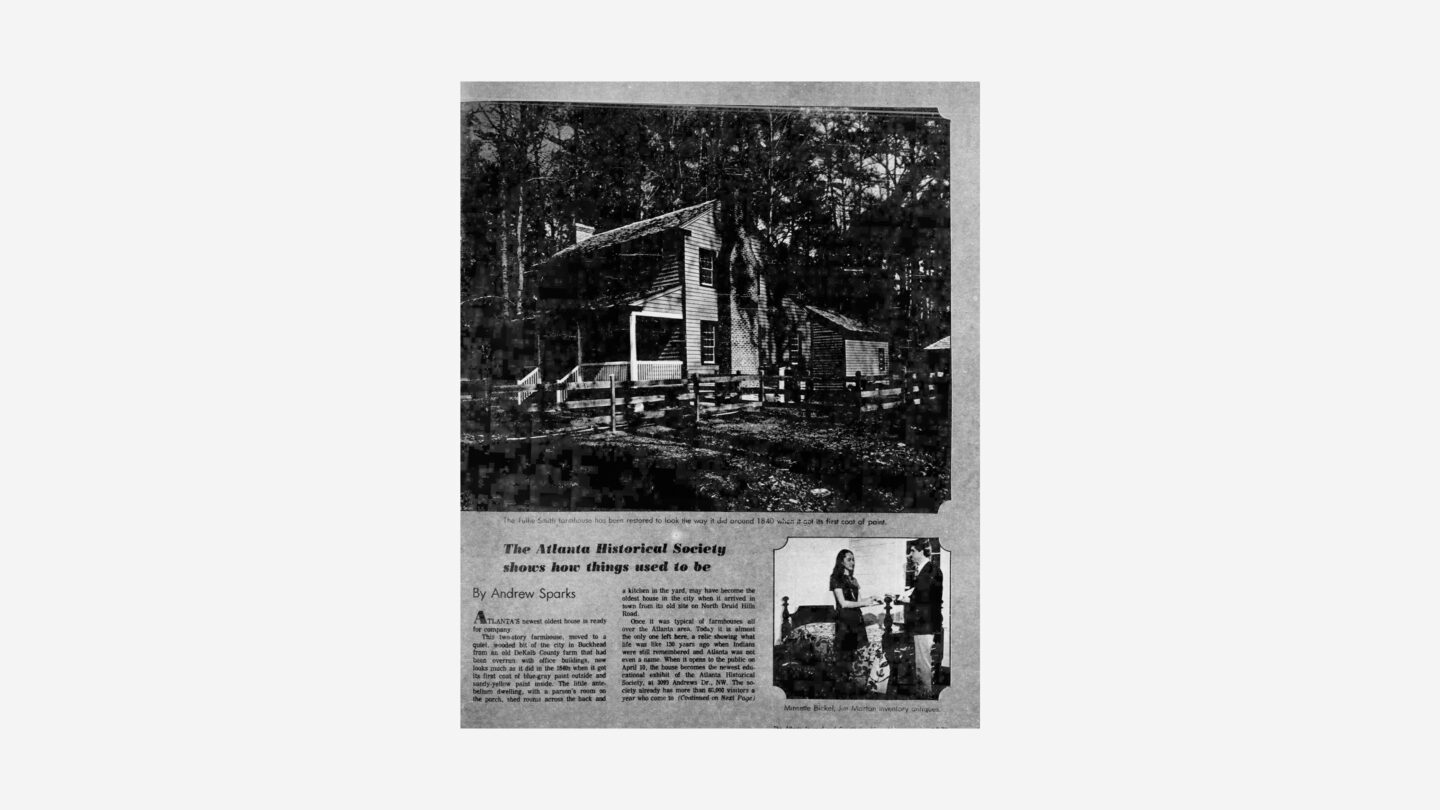

The house itself is a common style of Southern 19th-century vernacular architecture, though few examples exist today.

The house has a two-story front and a one-story rear, doors and glazed windows aligned to provide light and ventilation, and chimneys and fireplaces made of brick (reconstructed on site). The Smith House is also an “I” house, meaning it is two rooms deep, one-room depth, and two stories in height. The detached kitchen located behind the house was constructed around the same time as the house itself.

After the Civil War and emancipation, Robert and Elizabeth Smith retained ownership of the farm until 1875, when Robert died and Elizabeth moved away. A portion of the original acreage, including the farmhouse and kitchen, was purchased by William Berry Smith (Robert Hiram Smith’s grandson) and his wife Mary Ella in 1881. Their daughter, Tullie Vilenah Smith, would go on to live in the house until her death in 1967.

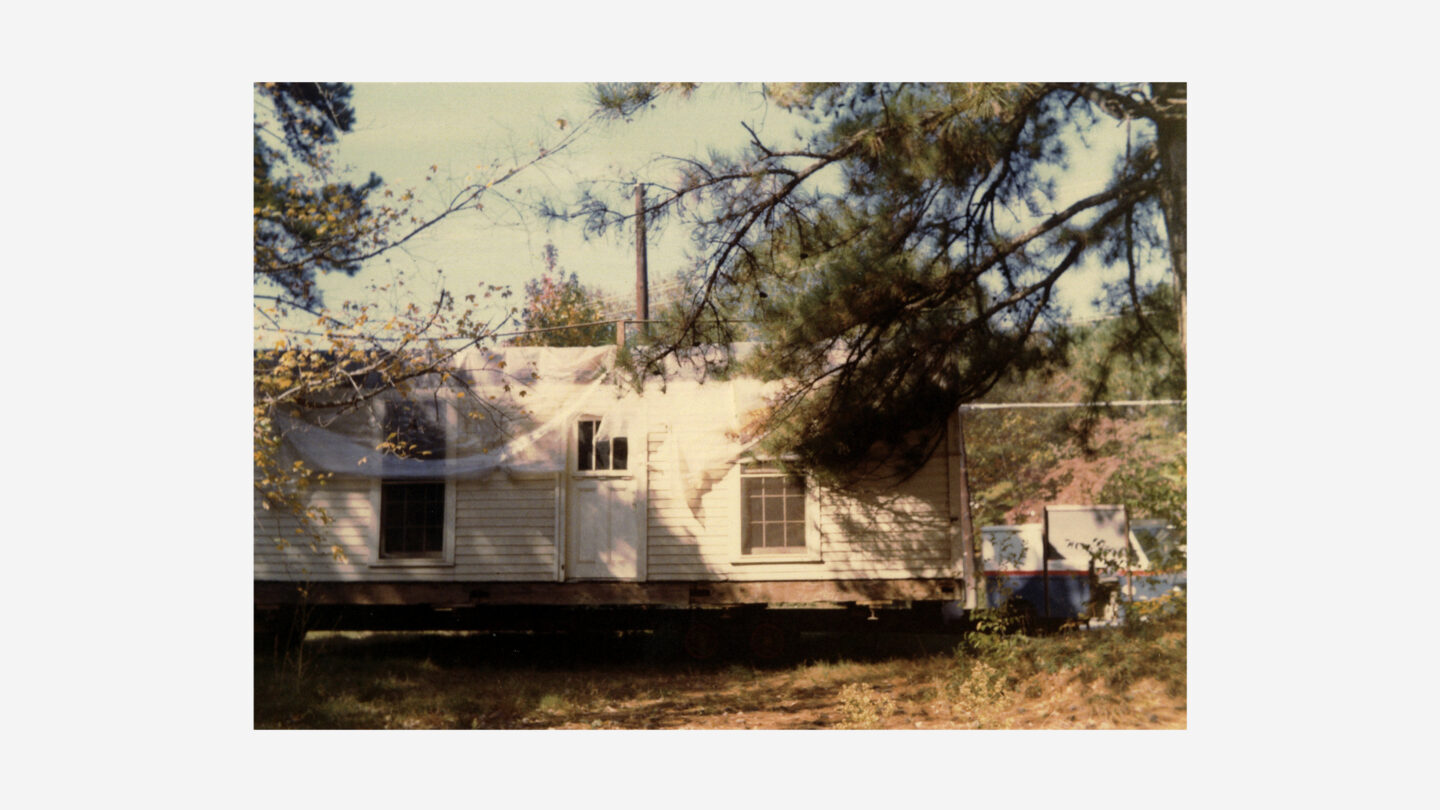

The Tullie Smith House in place at its Druid Hills location prior to its move to Atlanta History Center.

A Home and a Highway

As Atlanta grew following World War II, the Smith House, which had by now become known as the Tullie Smith House given Tullie Smith’s standing in the community, quickly became surrounded by development that threatened its survival. The construction of expressways, office parks, and other expansion was driven by the post-war boom. It also fueled the destruction of historic properties to make way for new development. As highways crept closer to the Tullie Smith House, the fate of the property was uncertain. Though its ailing owner wanted to preserve her historic home, Mrs. Smith did not make provisions before her death.

In 1969, the family of Tullie Smith gave the home to Atlanta History Center (AHC) following Mrs. Smith’s death in the house on July 27, 1967. The family contacted Mills B. Lane, well-known in business and political circles and passionate about historic preservation. Lane was president of Citizens & Southern National Bank (C&S) and a close friend of Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. Eventually, C&S Bank (now Bank of America) provided funds to move the house. Allen’s wife Louise Richardson Allen was highly involved with AHC.

Relocating the structures were no small task, especially the Tullie Smith House itself. The house could not be moved intact since it was too tall to clear power lines, trees, and traffic lights between its original location and its new Buckhead home. Hercules House Movers, working under general contractor Marvin M. Black, separated the first floor of the house from the second and moved the house in two large pieces. The house was stitched back together when it arrived at the Historical Society, after it was placed on a site which had been selected by landscape architects Edward Daugherty and Dan Franklin.

Once the Tullie Smith House and detached kitchen arrived at Atlanta History Center, the responsibility for the house fell to a passionate group of women volunteers. Recalling the day that the charismatic Mrs. Louise Allen asked her to chair a committee on the Tullie Smith House, Bettijo Cook Trawick recalled saying, “I don’t know anything about the 19th century,” given her expertise with 18th century antiques and history. Undeterred, Mrs. Allen informed her, “Well you can learn.”

Eventually, Mrs. Trawick agreed to chair the Tullie Smith House Restoration Committee. Fifty years later, recalling the state of the house, she remembered it being covered in mud and her friends teasing her for taking on such a project. Another volunteer, Sally Hawkins, soon became involved in the project as well after agreeing to conduct research on the house through her involvement in the Junior League of Atlanta. The two were soon joined by Florence Griffin, a former teacher and weather analyst who took on numerous volunteer projects related to antiques, history, and horticulture. “There wasn’t anything that Florence [and her husband] didn’t know,” Mrs. Hawkins remarked when remembering her friend, who died in 2008. Together, the three women tackled getting the house set in context with outbuildings, furnished, landscaped, and ready to open to the public. In a time when developers demolished historical buildings at a rapid clip, both preserving and enhancing such a structure was basically unheard of in Atlanta.

Transforming Tullie Smith House

Following two years of research, (and the listing of the house in the National Register of Historic Places in November 1970), the Tullie Smith House Restoration committee met January 27, 1971, and approved the restoration recommendations of cultural historian and historic preservationist William R. Mitchell, Jr. Shortly afterward, contractor W. Adrian Leavell was hired to complete the restoration work. That restoration work began in March 1971.

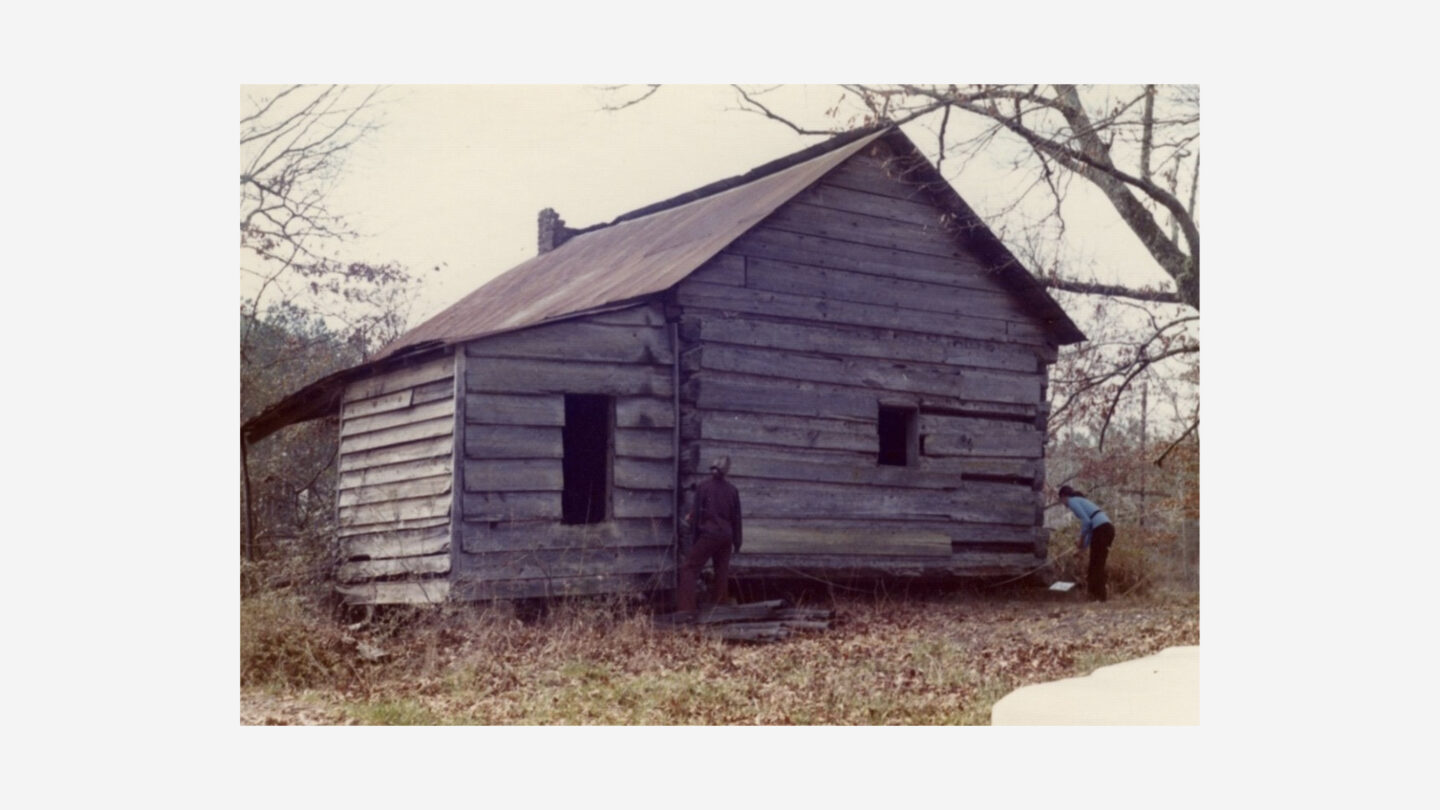

To furnish the house and complete the landscape, Mrs. Hawkins, Mrs. Trawick, and Mrs. Griffin traversed the state looking for suitable buildings, furnishings, and heirloom flowers and other plants for the surrounding landscape. The first outbuildings moved to accompany the house included the barn, originally built near Cartersville circa 1850. The volunteers then located a cabin, also dating from about 1850, and moved it onsite to allow for interpretation of enslaved life on a mid-19th Georgia Piedmont farm. Originally located in the Cliftondale area of Atlanta, the cabin’s architectural style was common in housing for enslaved individuals prior to the Civil War. The cabin briefly served as a craft shop at Smith Farm before that function was moved to the newly-built McElreath Hall. Over the years, the cabin has served as a vital component to supporting an accurate and complete depiction of the time period.

Gearing up for opening the farmhouse to the public, the institution and Mrs. Trawick hired Minnette Bickel (later Boesel) to serve as the first paid staff member to work at the farm. Mrs. Boesel got the job at Atlanta History Center right after completing her undergraduate degree in art history. She busied herself writing a detailed docent manual, learning crafts and trades for demonstrations that would take place on the farm, and developing educational tours for elementary school children (a key part of our visitors to the farm even today). Other volunteers and organizations pitched into the massive project, including notably the Poppy Garden Club, which Mrs. Boesel recalled providing high-quality costumes for the docents and Mrs. Trawick remembered also providing fresh plant material for holiday décor.

Mrs. Hawkins, Mrs. Trawick, and Mrs. Griffin also took on the furnishing of the farmhouse with 1840s furniture and led the creation and planting of a swept yard with heirloom flowers. At the end of a long day, the three women occasionally relaxed on the porch of the Tullie Smith House and enjoyed a glass of wine.

On April 10, 1972, Smith Farm opened to the public in a highly publicized event during Atlanta’s Dogwood Festival. A unique project, especially in its time, Smith Farm attracted widespread media attention in both local and national press.

Looking back at the massive undertaking and rapid speed of the Smith Farm project, President & CEO Sheffield Hale notes matter-of-factly, “Of course they did it in a few years. It was all led by women.”

After the Smith Farm opening, volunteers and staff members gradually began to move on to the next project. Mrs. Boesel pursued a master’s degree in historic preservation at Columbia University, later serving as the first Executive Director of the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation and beginning a long career in historic preservation. Mrs. Trawick became deeply involved in the Fox Theatre Preservation campaign, while Mrs. Hawkins and Mrs. Griffin assisted in creating the landmark Neat Pieces exhibition at Atlanta History Center. Even in 2022, though Mrs. Griffin, Mrs. Allen, and many others are gone, the remaining women who united behind the effort to move, preserve, and create the first iteration of Smith Farm’s interpretation still keep in close touch—a friendship now also celebrating 50 years.

Today, Smith Farm continues to serve as an educational and historical site.

50 Years Later

Smith Farm is a centerpiece of education on Atlanta History Center’s campus. The landscape now features live animals—heirloom breeds of Gulf Coast sheep, Angora goats, standard bronze turkeys, and Rhode Island red hens—as well as carefully curated gardens and landscapes, including the swept yard, kitchen garden, field, and enslaved people’s garden. That garden, located outside of the enslaved people’s cabin, features crops and planting styles reflective of those some enslaved individuals were allowed to plant to supplement their food rations. In a 2021 Garden & Gun article about that garden and its importance to telling the full story of farms, such as Smith Farm, James Beard Award-winning author and culinary educator Michael Twitty remarked, “It’s one of the most fantastic botanical landscapes, curated landscapes, in the South. … This is a shared history, and the way the Center tells these stories is revolutionary.”

As for the farmhouse and other outbuildings, Atlanta History Center staff continue to maintain and make appropriate changes to best preserve the structures and reflect the most historically accurate architecture, decoration, and construction, in both large and small ways. Most recently, a new fence installed in April 2022 more accurately depicts a similar type of fencing to what the Smith’s would have had on their property, while replacement of rotting roof timber and similar maintenance continues on a regular basis.

Even as the structures stay the same, interpretation and education continue to evolve on the farm, as well as at the entire institution. Fifty years provides a natural reflection point as Smith Farm—the first addition to the original Swan House property—enters a new era at a time when history is equal parts contested, questioned, and commemorated.

Recognizing the importance of the farm and its outbuildings—as well as its ongoing role in educating Atlanta residents and visitors to our city—on December 30, 2021, the Atlanta Urban Design Commission designated the Smith Farm as a City of Atlanta Historic Building Site.

When the Smith House was built approximately 180 years ago, Atlanta was a dot on a map, enslavement of humans was the law of the land, and the country was careening toward a bloody and violent Civil War. Fifty years ago, when the historic house opened, Atlanta was grappling with the recent assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., growing at a rapid pace and losing its historic structures in the process, and in the midst of a bloody, controversial war in Vietnam. These contexts for Smith Farm’s notable moments are a poignant reminder of all that our historic structures have seen, but also all that Atlantans have witnessed.

Place-based history has a role to play in ongoing deliberations over our history and future.

Through educational school tours, thoughtful curation of plants and animals, and continuous research through which new evidence is uncovered and new understandings are reached. As a result, we consistently update the interpretation of Smith Farm, allowing the landscape to serve as an immersive historical resource for people of all ages. The landscape also reminds us of how active and engaged community members can make a difference through a project, such as historic preservation. Historic preservation and studying the full, complex, sometimes difficult history of our community are ways that we can build a solid foundation for our shared future.