On Sunday, April 1, 2000, about 1,200 people came together to attend the Millennium Sunday convocation at Morehouse College. The event celebrated the Atlanta Civil Rights Movement and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his legacy. It culminated in the dedication and unveiling of a plaque that has the full text of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. King’s widow, Coretta Scott, and his son Martin Luther King III were in attendance, as were about 200 Freemasons dressed in full Masonic regalia.

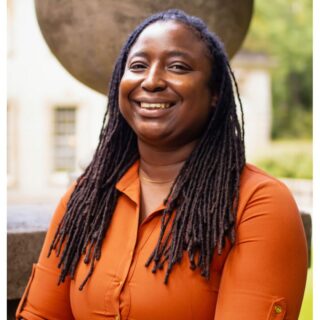

An Americorps VISTA worker poses in front of the Millenium Sunday plaque that contains the full text of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. (Morehouse College VISTA via Twitter)

After the event, a rumor circulated that Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia Grand Master Benjamin Barksdale, who had given remarks during the event, had made Dr. King a Mason at Sight at the ceremony.

A Mason at Sight is a non-Freemason raised to the degree of Master Mason through the authority of a grand master.

The news of King’s alleged appointment to Master Mason after death caused controversy in the Masonic world primarily because a dead person is not able to exercise one of the primary tenets of Freemasonry, which is joining of one’s own free will.

To become a Freemason, aspirants typically must go through a process by which they attain the first three degrees of Freemasonry. First, candidates are initiated and are known as Entered Apprentices. During this stage, they learn some of the secrets of Freemasonry and upon completion are entitled to be called “brother.”

Black and white photographic postcard of Daniel Hendricks wearing Masonic apron and collar. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Robin J. Boozé Miller)

After apprenticeship, they ascend to the next degree, which is called Fellowcraft. At the Fellowcraft stage, suppliants become journeymen of sorts, learning Masonic wisdom, symbolism, and philosophy at a higher level.

Finally, aspirants become Master Masons when they complete the third degree of Freemasonry and are elected to membership in a lodge. Master Masons are full-fledged members of the fraternal order and according to the website, Be a Freemason, “may enjoy both the rights and responsibilities of membership” and “visit lodges throughout the world.”

In an article in The Phylaxis, a magazine from the Phylaxis Society, an organization comprised of Prince Hall Freemasons, Barksdale sets the record straight.

“Dr. King is not a Mason,” Barksdale told the article’s author, Brother Burrell Parmer of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Texas. “You cannot make a dead person a Freemason.”

“Again Dr. King was never a Prince Hall Mason; however, with the permission of Mrs. Coretta Scott King, I was given permission to name a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. scholarship to assist a worthy young man to attend Morehouse College.”

The Prince Hall Masonic Temple on Auburn Avenue. (Wally Gobetz via Flickr)

The rumor started due to a misunderstanding from some in the audience at the Millennium Sunday event, said Past Master Douglas Evans, Past Grand Historian of Georgia, an associate of Barksdale’s who was in the audience during the ceremony.

“I was in the audience as a young five-year-old Mason when an honor was read by P.G.M. Barksdale in the company of Mrs. King and King III along with other Grand Lodge officers while on stage inside the King Chapel and I, as many others, thought that they were making Dr. King a Mason at Sight,” he said.

“I believe that during the ceremony as Mrs. King was on the stage was when P.G.M. Barksdale and the Masons announced that it was ‘honoring Dr. King’s death posthumously.’ I took it as something you might honor the governor or someone with, but the word posthumously made many feel as if Dr. King was being given the honor of being a Mason. I tend to believe that this was not the intent of P.G.M. Barksdale but maybe the wording of the statement was not filtered or edited enough.”

Though King was never made a Freemason, Ed Bowen, a 33rd degree Freemason and former legal advisor to the Prince Hall Masonic Temple on Auburn Avenue, believes it would have been only a matter of time before Dr. King became one, if he had lived.

Bowen said joining a Masonic lodge was a rite of passage for Black professionals.

“Most of the ministers on Auburn Avenue at that time were Masons, so were the most prominent doctors and lawyers,” he said. “The Masonic lodge was where you got stuff done.”

Freemasonry was also in Martin Luther King Jr.’s family. King’s father, Martin Luther King Sr., was a Freemason and so was his grandfather Rev. A.D. Williams. Many of King’s closest associates — Andy Young, Julian Bond, Hosea Williams, and John Lewis — were all Freemasons.

Mayoral candidate Andrew Young discusses the Atlanta election with John Lewis, Mayor Maynard Jackson, and wife Jean Childs Young in 1981. Young, Lewis, and Jackson were Masons and members of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia. (Jerome McClendon / AJC Archive at GSU Library AJCP549-016b)

In addition, the headquarters for King’s civil rights organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was located inside the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia on Auburn Avenue.

According to Bowen, another thing that might have enticed King to join the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Georgia and become a Freemason was the organization’s commitment to civil rights from its inception. The organization’s namesake, Prince Hall, was a free Black man who lived in colonial New England. He became a Freemason in 1775. When members of white lodges in Massachusetts wouldn’t admit Hall and fellow Blacks as members, Hall and his compatriots started their own lodge in 1784 with the backing of Freemasons in England. Since that time, the Prince Hall Freemasons have not only become the largest African American fraternal organization, but also the country’s oldest civil rights organization with its members advocating for a host of civil rights, including the abolition of slavery, free education for children, and equal pay for equal work.

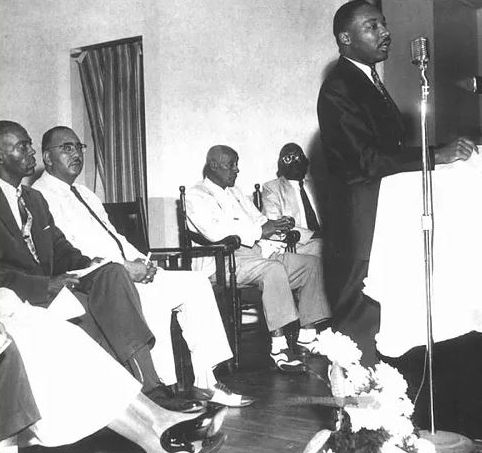

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speaks at the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge in Columbus, Ga., on July 1, 1958. (Columbus Black History Museum)

According to Christopher Hodapp, the author of Freemasons for Dummies, X.L. Neal, the Grand Master of the MWPHGLG, had planned to initiate King when he returned from Memphis in April 1968. King traveled to the area to lend his support to Black sanitation workers who were protesting unfair labor practices in the city.

Barksdale attests to this arrangement: “To the reference that G.M. Dr. X.L. Neal stated that he will make Dr. King a Prince Hall Mason at Sight when he returns from Memphis: The above is true. I was Grand Senior Warden when G.M. Neal made the statement which was in the presence of the Grand Lodge membership in Augusta, Ga.”

Due to an assassin’s bullet, King never made it back to Atlanta alive.

He died in the emergency room on April 4, 1968, at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Memphis, an hour after being shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

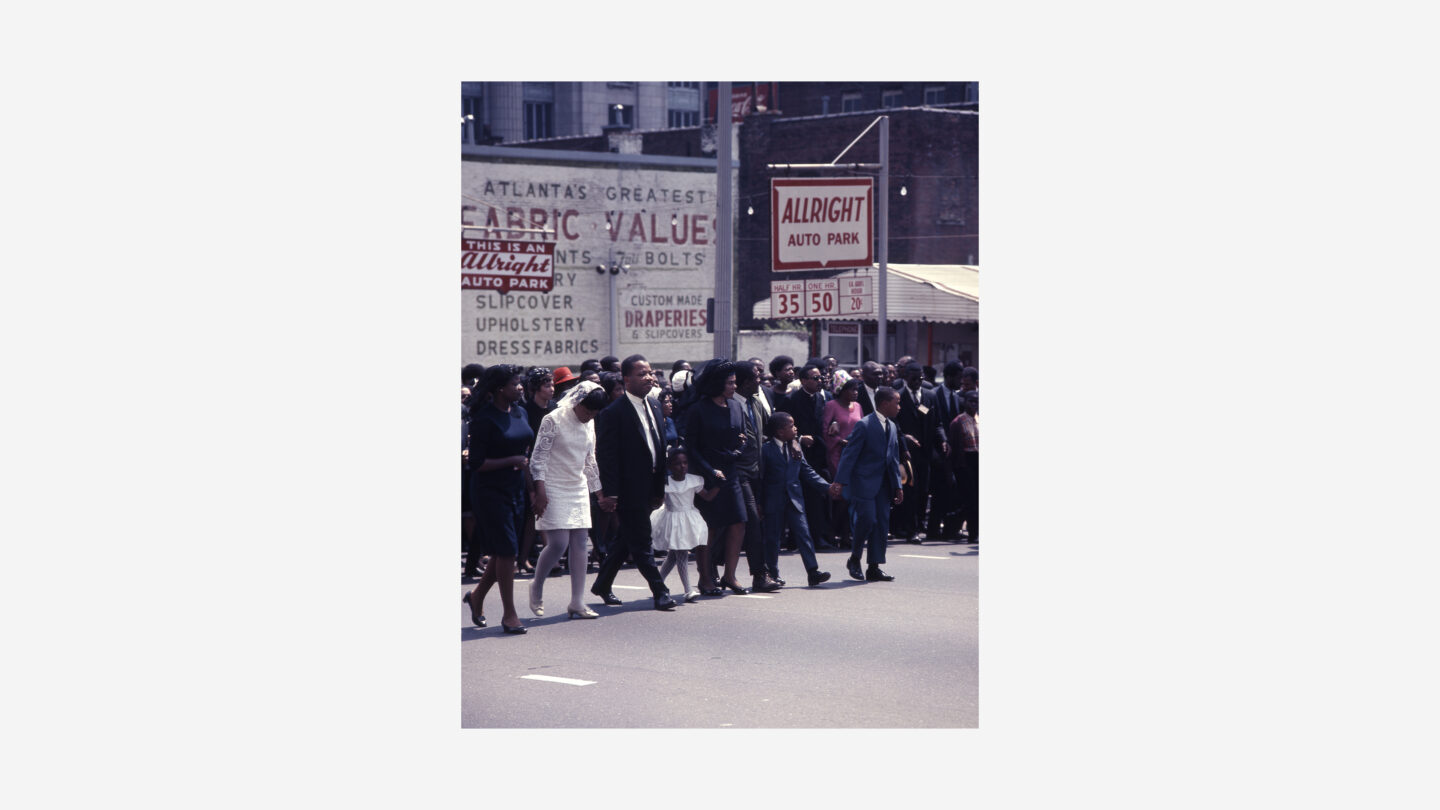

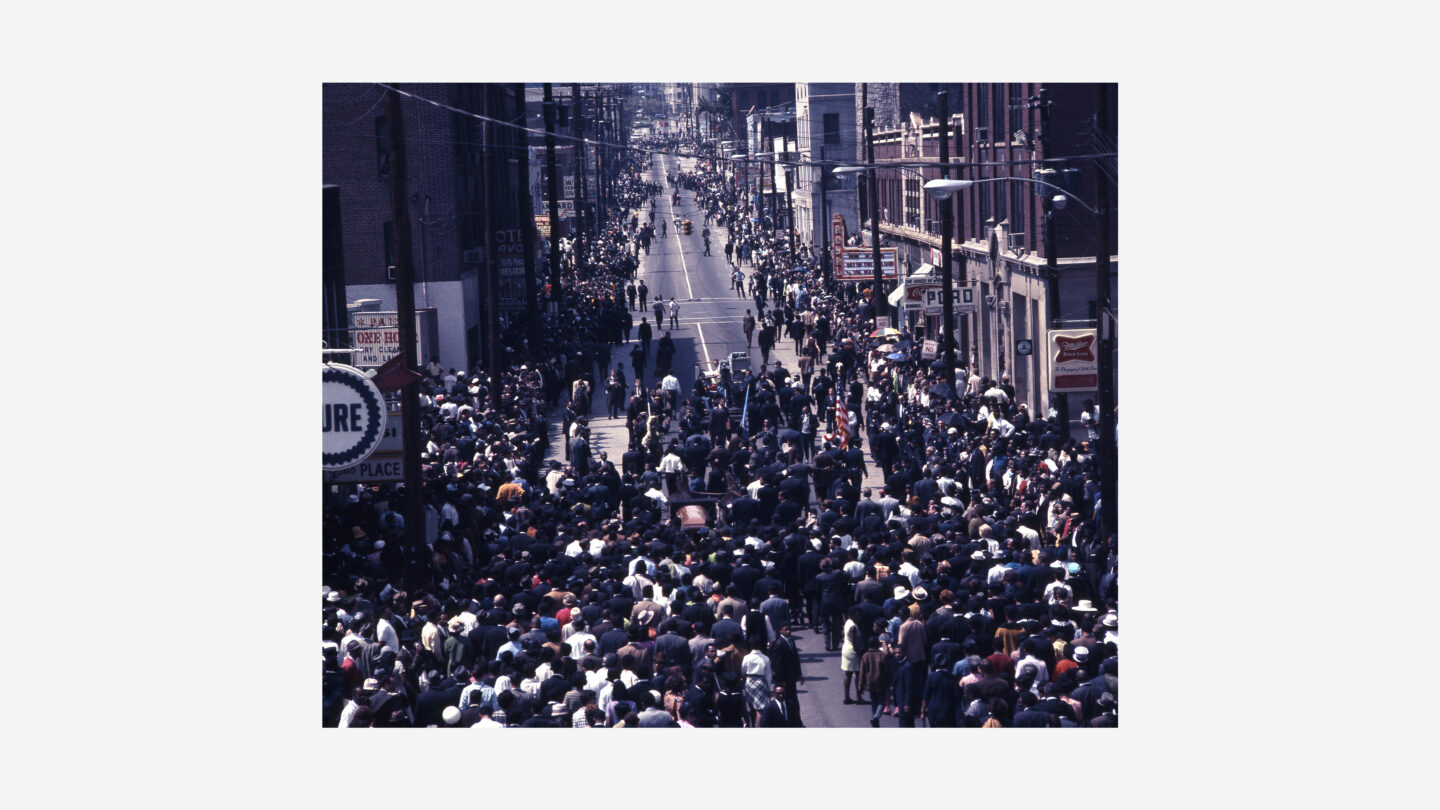

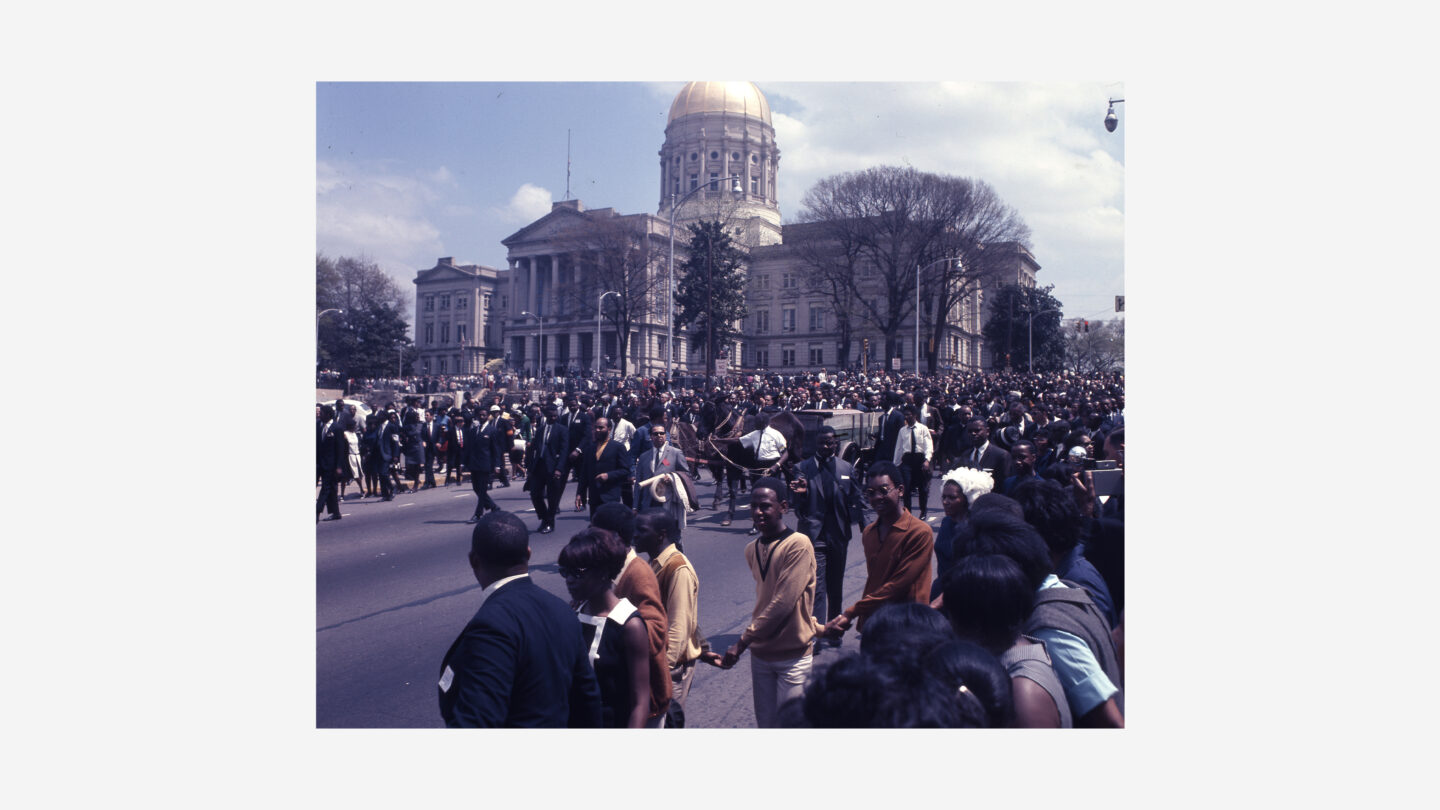

After a private memorial service in Memphis at R.S. Lewis & Sons Funeral Home, King’s body was flown back to Atlanta. Later, on April 9, 1968, family and close friends gathered for a private funeral service at Ebenezer Baptist Church.

A program for the funeral services for Martin Luther King, Jr. at Ebenezer Baptist Church and Morehouse College on April 9, 1968. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

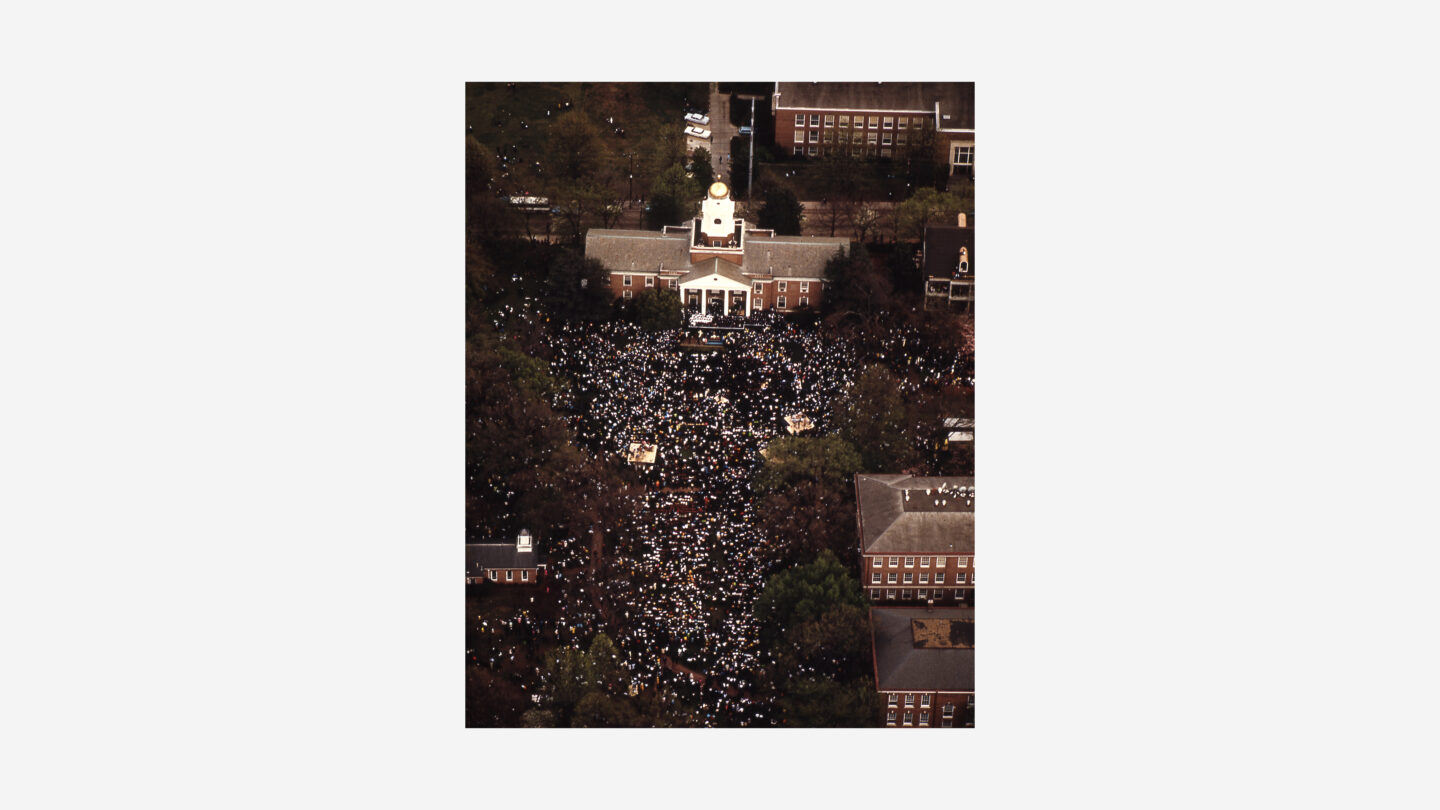

A public memorial followed the private funeral. King’s casket was loaded onto a simple mule-driven cart. The mules, Belle and Ada from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, led the procession. As the wagon began its four-mile trek from Ebenezer Baptist Church to its destination, thousands of people, including King’s family, acolytes, friends, and supporters, fell in line and joined the procession. They walked slowly, quietly, mournfully behind his casket, as it made its way to Morehouse College. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy officiated at the public service. King’s mentor, educator Benjamin Mays, delivered a eulogy entitled, “No Man is Ahead of his Time.” Other distinguished speakers paid their respects and Gospel legend Mahalia Jackson sang King’s favorite hymn, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.” King’s last words were reportedly a request for the song.

After those gathered sang “We Shall Overcome,” a popular anthem of the Civil Rights Movement, King’s casket was taken to South-View Cemetery, the oldest African American cemetery in Atlanta. There, he was laid to rest until his body was moved to a tomb at the King Memorial in 1982.

Though King never became a full-fledged Freemason, Bowen said he thinks King already embodied the spirit of Freemasonry.

“Everything it means to be a Mason, he was doing all along. … Setting a good moral example, charitable work, being a good citizen. He was already doing that,” Bowen said.

“He already represented what was best in the character of a man.”