Reverend Fred Bennett, Mr. Isaac Farris, Mrs. Christine King Farris, Reverend Ralph D. Abernathy, Dr. Roy C. Bell, Mrs. Clarice Wyatt Bell, and Mr. and Mrs. King enjoying a meal at Paschal’s Restaurant in 1962. Photo retrieved from paschalsatlanta.com and Dr. Clarice Bell via Flickr.

Football teams. Religion. Politics. There’s not a lot that Southerners agree on. The one exception is food. Cooked well and seasoned just right, a crispy piece of fried chicken, a warm, buttery biscuit, or a side of creamy macaroni and cheese not only fills you up physically, but it can also affect you on a spiritual level.

Perhaps this is the reason some of Atlanta’s most beloved restaurants serve up “soul food.” In addition to being a balm for the soul, soul food and soul food restaurants served as a backdrop for Atlanta’s civil rights movement, and many of the great, seemingly impossible things civil rights icons did or endured can be traced back to modest tables and booths in bustling restaurants.

Throughout the civil rights movement in Atlanta, soul food restaurants were hubs of change where civil rights leaders could convene, converse, and strategize, and in times of terror and violence, these places were retreats where leaders could plan their next tactical moves, giving many of these spots a legacy beyond good cooking.

James and Robert Paschal pose for a photograph inside Paschal’s Motor Hotel and Restaurant. (Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive.)

Paschal’s Restaurant | Originally at 837 West Hunter Street; Now at 180 Northside Drive SW

Brothers James and Robert Paschal started Paschal’s Motor Hotel and Restaurant in 1947. At its original location on West Hunter Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Drive), the restaurant was conveniently located on the route to work for many politicians and civil rights leaders. Sometimes they would stop by the restaurant for a quick bite to eat, but other times they visited Paschal’s for meetings that lasted long into the night. The comfort food that Paschal’s served civil rights freedom fighters included Creole dishes such as gumbo, catfish etouffee, and a fried chicken recipe created by Robert that is still top-secret to this day. In the 1950s and 1960s, civil rights movement icons such as Andrew Young, John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and Jesse Jackson were frequent diners. John Lewis described the restaurant as a haven to which he could retreat after “arrests, death threats, and beatings.”

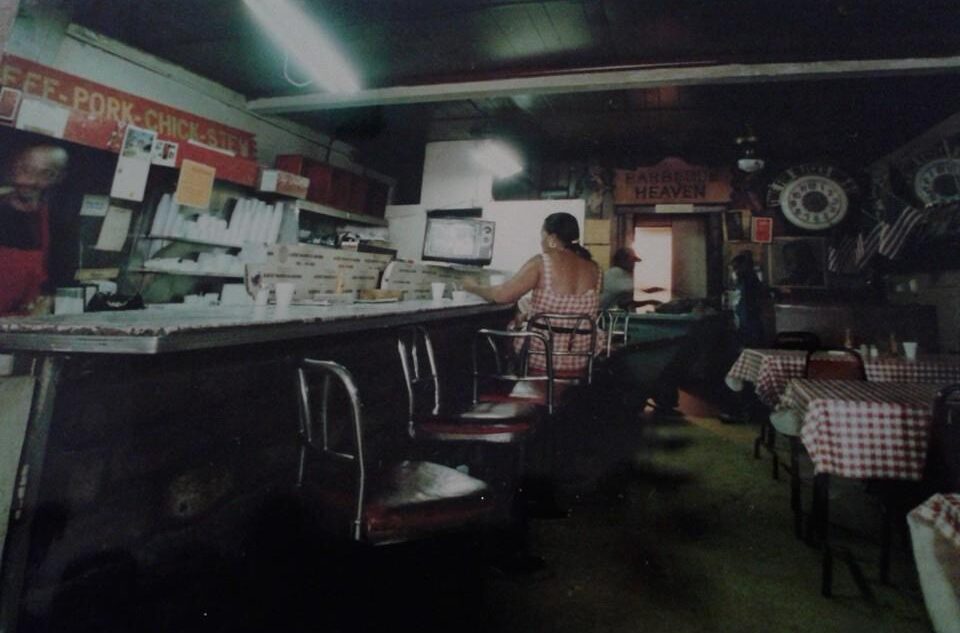

An interior view of Aleck’s Barbecue Heaven. (Photo courtesy Pam Alexander)

Aleck’s Barbecue Heaven | 783 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive

While in business, Aleck’s Barbecue Heaven served up the best of its name. Ernest Alexander founded Aleck’s Barbecue Heaven in 1942 and kept guests returning with his smoked barbecue and famous “Come Back” sauce. One of those loyal guests was Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the restaurant was reportedly one of his favorite restaurants. Aleck’s was located near the West Hunter Street Baptist Church, where Rev. Ralph Abernathy, one of Dr. King’s closest advisors and friends, preached. When Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, the restaurant erected a shrine in honor of the leader in his favorite booth. Unfortunately, the City of Atlanta demolished Aleck’s to make way for a Publix (now a Walmart) in the late 1990s, taking its sacred history with it.

President Joe Biden poses with patrons outside of the Busy Bee Café. (Adam Shultz, Biden for President)

Busy Bee Café | 810 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive

The Busy Bee Cafe buzzed to life in 1947, thanks to founder Lucy Jackson. Jackson, who was affectionately known as “Mama Lucy,” specialized in home cooking and earned her moniker due to her founding intent to feed everyone who walked through the café’s doors. Paschal’s Restaurant and the Busy Bee Café were both on West Hunter Street due to Jim Crow laws that restricted where black-owned businesses could be established. Despite this constraint, there were more than enough patrons in the area for Paschal’s and the Busy Bee Cafe, and Jackson became a successful business owner. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., visited the café frequently and was said to have been a fan of the ham hocks. Ownership of the café has changed throughout the years, but Tracy Gates has owned the café since 1987. Presidents Obama, Biden, and Sen. Bernie Sanders have visited in recent years.

View of Maj. Howard Baugh of the City of Atlanta Police Department and State Representative E. J. Shepherd at Shepherd’s restaurant at 11 Butler Street (now Jesse Hill Jr. Drive) in Atlanta, Georgia. (Boyd Lewis Photographs, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

Shepherd’s Home Cooked Foods | 11 Butler Street

Opening a bit after the 1954-1968 civil rights movement, Shepherd’s Home Cooked Foods was an important spot to local politicians of the 1970s. Shepherd’s bridged the worlds of politics and food through its owner, E.J. Shepherd, who was a Georgia State representative and restaurateur. Shepherd represented District 28 of Fulton County in the Georgia House of Representatives from 1969 to 1974. During his term, he opened Shepherd’s Home Cooked Foods on Butler Street (now Jesse Hill Jr. Drive) in 1971, and the restaurant became a favorite of politicians such as Ben Brown and Arthur Langford. Shepherd’s struggled financially during its existence, not for lack of taste – the Atlanta Constitution lauded their grits as some of the best in Atlanta — but because Shepherd was a good Samaritan first and a businessman second. “He gave away as much food as he sold,” some remarked in the Atlanta Constitution, speaking of how Shepherd fed hungry people who came to the restaurant. The restaurant closed in 1984.