1/6 Intro to Artifacts

Army of the James Medal for Valor, 1865

This is the only medal created for the U.S. Colored Troops. Major General Benjamin Butler, commander of the Army of the James, personally commissioned 197 of these medals to commemorate the valor of USCT soldiers at the Battle of New Market Heights, Virginia, on September 29, 1864. The silver medal bears the Latin phrase FERRO IIS LIBERTAS PERVENIET [FREEDOM WILL BE THEIRS BY THE SWORD]. We do not know to whom this particular medal was awarded.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2020

Army of the James Medal for Valor, 1865

This is the only medal created for the U.S. Colored Troops. Major General Benjamin Butler, commander of the Army of the James, personally commissioned 197 of these medals to commemorate the valor of USCT soldiers at the Battle of New Market Heights, Virginia, on September 29, 1864. The silver medal bears the Latin phrase FERRO IIS LIBERTAS PERVENIET [FREEDOM WILL BE THEIRS BY THE SWORD]. We do not know to whom this particular medal was awarded.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2020

Private Scott Green’s Discharge Papers and Rifle-Musket, 1st U.S. Colored Infantry, 1865

Born a free man in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Scott Green was 19 when he enlisted near Washington, D.C., on June 30, 1863. Wounded at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, Virginia, on October 27, 1864, Green was hospitalized for the next eleven months. It is believed he took home this British Pattern 1853 rifle-musket when he was discharged on September 29, 1865. It may be the one he carried at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. The lock is a replacement.

Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. William S. Jackson, 1989

Private Scott Green’s Discharge Papers and Rifle-Musket, 1st U.S. Colored Infantry, 1865

Born a free man in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Scott Green was 19 when he enlisted near Washington, D.C., on June 30, 1863. Wounded at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, Virginia, on October 27, 1864, Green was hospitalized for the next eleven months. It is believed he took home this British Pattern 1853 rifle-musket when he was discharged on September 29, 1865. It may be the one he carried at the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm. The lock is a replacement.

Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. William S. Jackson, 1989

Private Scott Green’s Veteran Sword, circa 1885

After the war, 1st U.S. Colored Infantry veteran Scott Green settled in Boston, Massachusetts. There he joined the all-Black Robert A. Bell Post 134 of the Grand Army of the Republic, the national Union veterans’ organization. G.A.R. members wore ceremonial uniforms, caps, and swords; elected positions of leadership were titled by military rank. Green served as Post Surgeon from 1905 through his death in 1917 at the age of 75. The Abiel Smith School which once housed the Bell G.A.R. Post is now part of Boston’s Museum of African American History.

Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. William S. Jackson, 1989

Private Scott Green’s Veteran Sword, circa 1885

After the war, 1st U.S. Colored Infantry veteran Scott Green settled in Boston, Massachusetts. There he joined the all-Black Robert A. Bell Post 134 of the Grand Army of the Republic, the national Union veterans’ organization. G.A.R. members wore ceremonial uniforms, caps, and swords; elected positions of leadership were titled by military rank. Green served as Post Surgeon from 1905 through his death in 1917 at the age of 75. The Abiel Smith School which once housed the Bell G.A.R. Post is now part of Boston’s Museum of African American History.

Courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. William S. Jackson, 1989

Private Ezra Brooks’s Knapsack, 8th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1864

In 1863, soldiers of the newly formed 8th regiment were outfitted with these distinctive calfskin knapsacks imported from France. Private Ezra Brooks, a free African American farmer from New York, wore this one at the Battle of Olustee Florida in 1864. Brooks survived the battle and the war, but the 8th suffered the most combat deaths of any USCT regiment.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2006

Private Ezra Brooks’s Knapsack, 8th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1864

In 1863, soldiers of the newly formed 8th regiment were outfitted with these distinctive calfskin knapsacks imported from France. Private Ezra Brooks, a free African American farmer from New York, wore this one at the Battle of Olustee Florida in 1864. Brooks survived the battle and the war, but the 8th suffered the most combat deaths of any USCT regiment.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2006

Thomas Baker’s Drum, 55th Massachusetts Infantry, 1864

The 55th Massachusetts Regiment was formed at the same time as the more famous 54th (portrayed in the 1989 movie Glory). In October 1864, soldiers of the 55th raised enough money to buy new brass instruments for their drum corps. This one is inscribed with the name of its owner: Drummer Thomas Baker, an 18-year-old farm laborer from Xenia, Ohio. He used this drum during the siege of Charleston and at the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2011

Thomas Baker’s Drum, 55th Massachusetts Infantry, 1864

The 55th Massachusetts Regiment was formed at the same time as the more famous 54th (portrayed in the 1989 movie Glory). In October 1864, soldiers of the 55th raised enough money to buy new brass instruments for their drum corps. This one is inscribed with the name of its owner: Drummer Thomas Baker, an 18-year-old farm laborer from Xenia, Ohio. He used this drum during the siege of Charleston and at the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2011

A Canteen of the 15th U.S. Colored Infantry, circa 1864

The personalized “15 USCT” inked stamp on this U.S. Army canteen indicates use by the 15th Regiment, which guarded the vital U.S. supply depots in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1864 and 1865. The upholstery fabric cover helped keep the water cool.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2019

Private Curtis’s Musket, 36th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1863

The inscription “JA W.H. CURTIS Co.I” in the stock of this U.S. Model 1816 percussion-altered musket is believed to be that of Private James H. (or W.H.) Curtis of Company I, 36th U.S. Colored Infantry. The formerly enslaved man enlisted at Portsmouth, Virginia, in September 1863. He fought in six major battles before he was mustered out at Galveston, Texas, in 1866. The musket was discovered in a Charleston, South Carolina, antique store in the 1960s.

Courtesy Randall B. Burbage in memory of Manning B. Williams Jr., 2023

Private Curtis’s Musket, 36th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1863

The inscription “JA W.H. CURTIS Co.I” in the stock of this U.S. Model 1816 percussion-altered musket is believed to be that of Private James H. (or W.H.) Curtis of Company I, 36th U.S. Colored Infantry. The formerly enslaved man enlisted at Portsmouth, Virginia, in September 1863. He fought in six major battles before he was mustered out at Galveston, Texas, in 1866. The musket was discovered in a Charleston, South Carolina, antique store in the 1960s.

Courtesy Randall B. Burbage in memory of Manning B. Williams Jr., 2023

A Soldier’s Commemorative Badge, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1865

Soldiers often purchased badges customized with their name and battle record as a memento of military service. This one bears the name of Private Benjamin George Hannan, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry. There is no record of a soldier with this name in the 97th regiment. Like many in the USCT, this man may have enlisted under another name so that if captured he could not be identified and re-enslaved.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2019

A Soldier’s Commemorative Badge, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1865

Soldiers often purchased badges customized with their name and battle record as a memento of military service. This one bears the name of Private Benjamin George Hannan, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry. There is no record of a soldier with this name in the 97th regiment. Like many in the USCT, this man may have enlisted under another name so that if captured he could not be identified and re-enslaved.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2019

An 18-Year-Old Lieutenant’s Sword, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1864

Lieutenant Frederick D. Burnham, a White Harvard student from Newburyport, Massachusetts, carried this sword on December 17, 1864, as he led the charge of Company K, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, across a bridge on the Escambia River in western Florida. A Confederate buckshot round (like shotgun pellets) shattered his left leg. Burnham never fully recovered. He died in 1874 at the age of 27.

Courtesy The Nau Civil War Collection, Houston, Texas, 2023

An 18-Year-Old Lieutenant’s Sword, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, 1864

Lieutenant Frederick D. Burnham, a White Harvard student from Newburyport, Massachusetts, carried this sword on December 17, 1864, as he led the charge of Company K, 97th U.S. Colored Infantry, across a bridge on the Escambia River in western Florida. A Confederate buckshot round (like shotgun pellets) shattered his left leg. Burnham never fully recovered. He died in 1874 at the age of 27.

Courtesy The Nau Civil War Collection, Houston, Texas, 2023

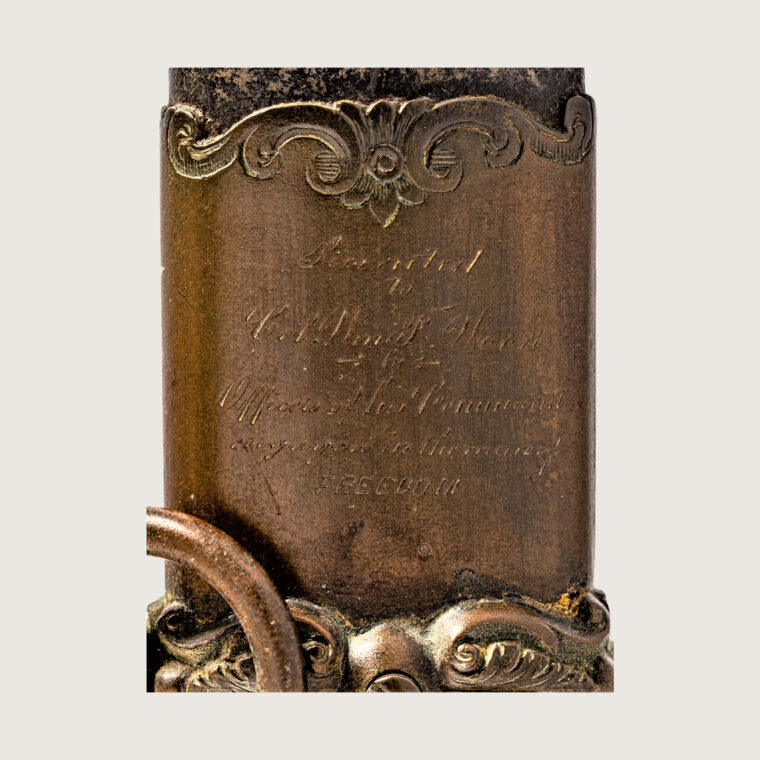

Colonel William F. Wood, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry: “Engaged in the cause of FREEDOM,” 1863

The inscription on the scabbard of this sword tells its story: “Presented to Col. Wm. F. Wood by Officers of his Command engaged in the cause of FREEDOM.” In May 1863, Wood took command of the 1st Arkansas Infantry of African Descent, the first Black regiment raised in the Mississippi River Valley. In 1864 the regiment was re-designated as the 46th U.S. Colored Infantry. Wood suffered wounds, injuries, and illness, but survived the war and lived out his life as a Baptist minister in Cuba and Florida.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2014

Colonel William F. Wood, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry: “Engaged in the cause of FREEDOM,” 1863

The inscription on the scabbard of this sword tells its story: “Presented to Col. Wm. F. Wood by Officers of his Command engaged in the cause of FREEDOM.” In May 1863, Wood took command of the 1st Arkansas Infantry of African Descent, the first Black regiment raised in the Mississippi River Valley. In 1864 the regiment was re-designated as the 46th U.S. Colored Infantry. Wood suffered wounds, injuries, and illness, but survived the war and lived out his life as a Baptist minister in Cuba and Florida.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2014

Colonel William F. Wood, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry: “Engaged in the cause of FREEDOM,” 1863

The inscription on the scabbard of this sword tells its story: “Presented to Col. Wm. F. Wood by Officers of his Command engaged in the cause of FREEDOM.” In May 1863, Wood took command of the 1st Arkansas Infantry of African Descent, the first Black regiment raised in the Mississippi River Valley. In 1864 the regiment was re-designated as the 46th U.S. Colored Infantry. Wood suffered wounds, injuries, and illness, but survived the war and lived out his life as a Baptist minister in Cuba and Florida.

Purchase with funds from Anonymous Donor, 2014

Sweetheart Locket with Soldier’s Portrait, circa 1864

Who was this soldier? Who loved him and wore this locket? During the Civil War, photographers did a booming business making portraits for loved ones separated by the war. An artist highlighted this one with gold paint and added an orange glow to the tip of the cigar. This young man seems ready to speak to us, but since there is no inscription in the locket, we may never know his story.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Sweetheart Locket with Soldier’s Portrait, circa 1864

Who was this soldier? Who loved him and wore this locket? During the Civil War, photographers did a booming business making portraits for loved ones separated by the war. An artist highlighted this one with gold paint and added an orange glow to the tip of the cigar. This young man seems ready to speak to us, but since there is no inscription in the locket, we may never know his story.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Sweetheart Locket with Soldier’s Portrait, circa 1864

Who was this soldier? Who loved him and wore this locket? During the Civil War, photographers did a booming business making portraits for loved ones separated by the war. An artist highlighted this one with gold paint and added an orange glow to the tip of the cigar. This young man seems ready to speak to us, but since there is no inscription in the locket, we may never know his story.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

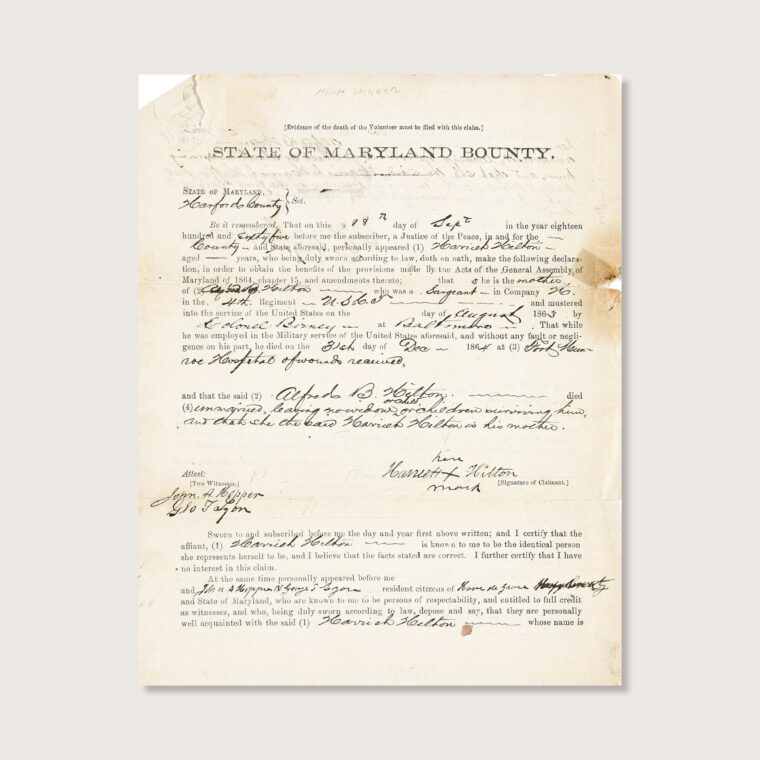

A Mother’s Application for Benefits, 1865

Harriett Hilton was a 58-year-old free woman of color living in Maryland. All three of her sons volunteered for the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry. Alfred, her 26-year-old middle son and the regimental flag-bearer, died of wounds after helping rally his men at the Battle of New Market Heights, Virginia, September 29, 1864. For his actions, Sergeant Hilton earned the Army of the James Medal as well as the Congressional Medal of Honor. For her loss, Harriet Hilton was allocated the $300 “bounty” or enlistment bonus Alfred had set aside in case of his death.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Slave Hire Badges, South Carolina, 1801 and 1817

Charleston authorities required enslaved artisans to wear one of these copper badges as a means of distinguishing between free and enslaved laborers. Wages earned by the enslaved went to the “owner.” The badge for a “Porter” (1801) was excavated on the Isle of Palms; the one for a “Fisher” (1817) was found at the site of a Union Army camp on Folly Island.

Thomas Swift Dickey Civil War Ordnance Collection, 1987

Slave Hire Badges, South Carolina, 1801 and 1817

Charleston authorities required enslaved artisans to wear one of these copper badges as a means of distinguishing between free and enslaved laborers. Wages earned by the enslaved went to the “owner.” The badge for a “Porter” (1801) was excavated on the Isle of Palms; the one for a “Fisher” (1817) was found at the site of a Union Army camp on Folly Island.

Thomas Swift Dickey Civil War Ordnance Collection, 1987

“AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER,” circa 1797

This British abolitionist coin was one of the first mass-produced political symbols, a forerunner of the modern protest badge. Beginning in 1787, English ceramics maker Josiah Wedgwood incorporated the logo into medallions, plates, jewelry, and other products. Benjamin Franklin helped popularize the logo in the United States. Great Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

“AM I NOT A MAN AND A BROTHER,” circa 1797

This British abolitionist coin was one of the first mass-produced political symbols, a forerunner of the modern protest badge. Beginning in 1787, English ceramics maker Josiah Wedgwood incorporated the logo into medallions, plates, jewelry, and other products. Benjamin Franklin helped popularize the logo in the United States. Great Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

“AM I NOT A WOMAN AND A SISTER,” 1838

American abolitionists quickly adopted the powerful logo that Josiah Wedgwood had popularized in Britain. This coin depicting a woman in chains was minted in the United States to commemorate British abolition laws and encourage American efforts toward the same goal.

Gift of Frank L. Edwards, 1995

“AM I NOT A WOMAN AND A SISTER,” 1838

American abolitionists quickly adopted the powerful logo that Josiah Wedgwood had popularized in Britain. This coin depicting a woman in chains was minted in the United States to commemorate British abolition laws and encourage American efforts toward the same goal.

Gift of Frank L. Edwards, 1995

![“Commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage,” [Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery] 2007](https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/app/uploads/2021/11/16-1_USCT_NewObjects-760x760.jpg)

“Commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage,” [Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery] 2007

The French-speaking West African nation of Ivory Coast used Josiah Wedgwood’s famous abolitionist logo to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the end of the British Trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807. The 2500-franc silver coin is worth about 25 U.S. dollars.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

![“Commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage,” [Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery] 2007](https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/app/uploads/2021/11/16_USCT_NewObjects-760x760.jpg)

“Commémoration de l'abolition de l'esclavage,” [Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery] 2007

The French-speaking West African nation of Ivory Coast used Josiah Wedgwood’s famous abolitionist logo to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the end of the British Trans-Atlantic slave trade in 1807. The 2500-franc silver coin is worth about 25 U.S. dollars.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Commemorative Figurine of John Brown, 1860

In October 1859, militant abolitionist John Brown and 21 armed men seized the U.S. Armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an unsuccessful effort to spark a war against slavery. Tried and executed two months later, Brown was the very embodiment of the slavery debate. This ceramic figurine made in Staffordshire, England, depicts Brown as northern anti-slavery and abolitionist activists preferred to see him: a kindly, paternalistic savior of enslaved children.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2022

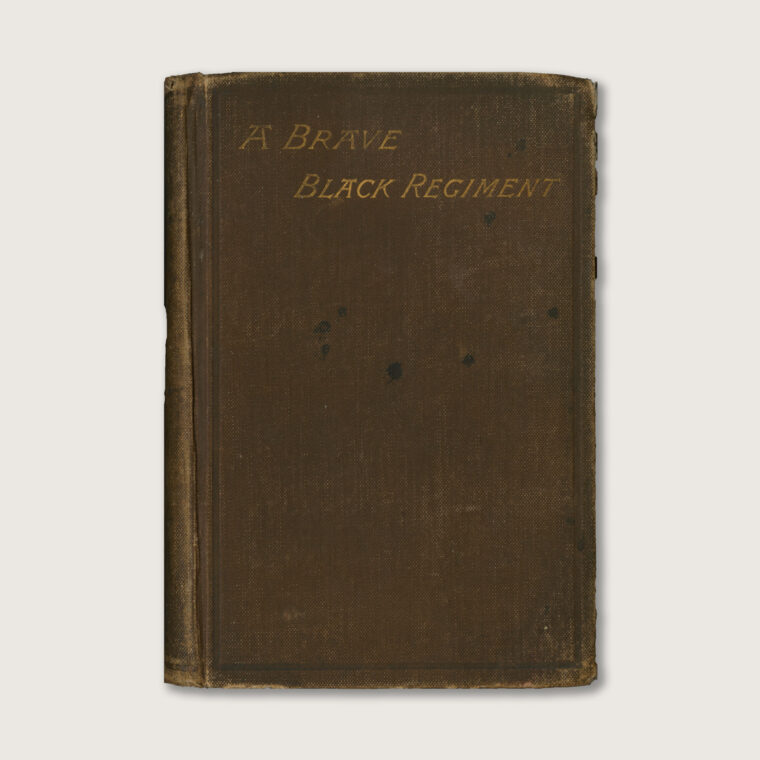

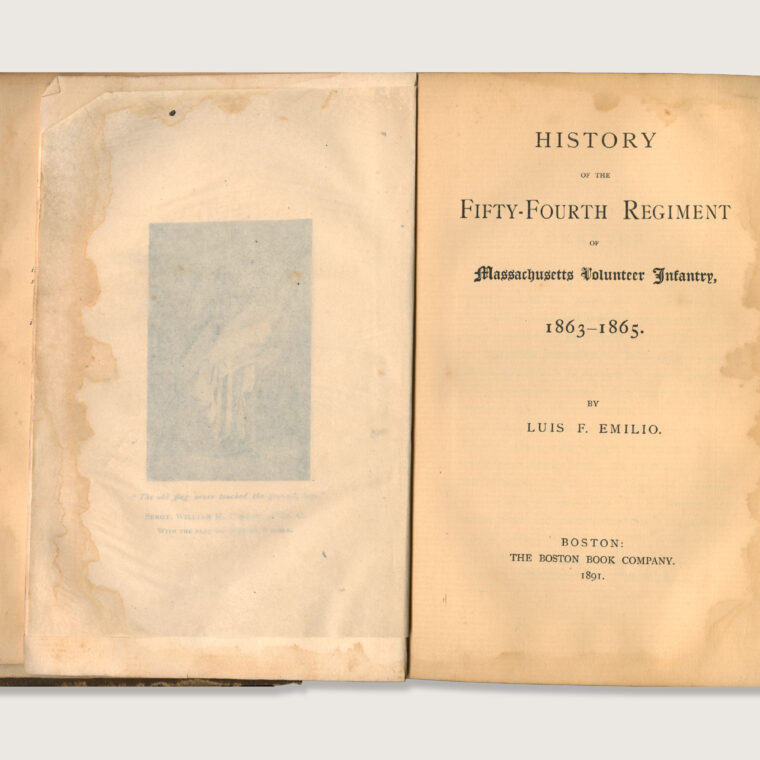

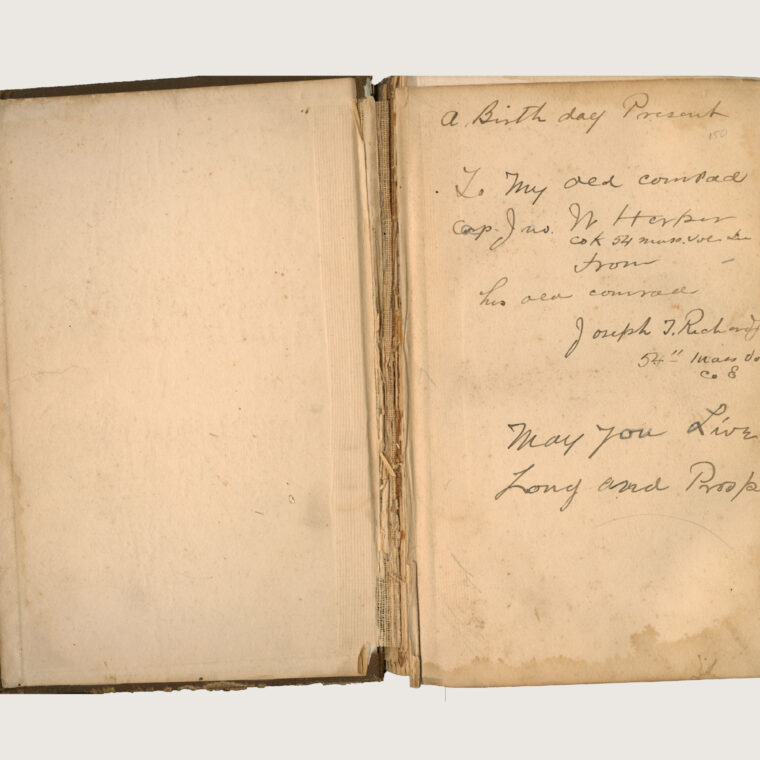

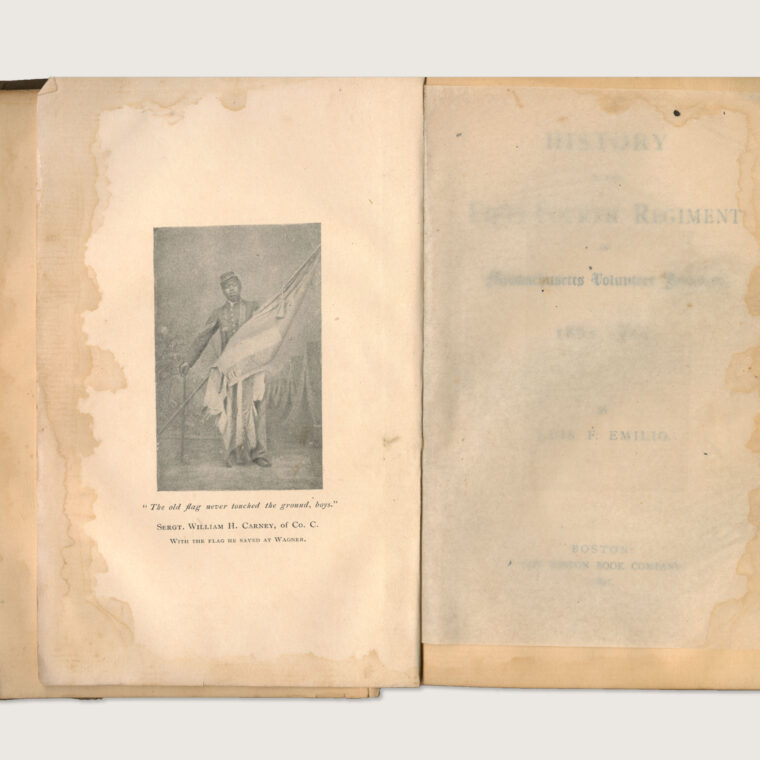

Brothers in Arms: “May you live long and prosper,” 1891

In 1863, the 54th Massachusetts became the first Black regiment raised in the North. In 1891, 54th veteran Joseph J. Richardson, a successful tradesman in Chicago, purchased a copy of the new regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment and presented it as a birthday present to “my old comrade,” ex-54th corporal John W. Harper, now a sergeant major in the 25th U.S. Infantry (“Buffalo Soldiers”). Richardson added a simple heartfelt wish: “May you live long and prosper.” Richardson died in a veterans’ home in 1915 at the age of 70. Harper retired from the Army in 1895 and died in 1920 at the age of 80.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Brothers in Arms: “May you live long and prosper,” 1891

In 1863, the 54th Massachusetts became the first Black regiment raised in the North. In 1891, 54th veteran Joseph J. Richardson, a successful tradesman in Chicago, purchased a copy of the new regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment and presented it as a birthday present to “my old comrade,” ex-54th corporal John W. Harper, now a sergeant major in the 25th U.S. Infantry (“Buffalo Soldiers”). Richardson added a simple heartfelt wish: “May you live long and prosper.” Richardson died in a veterans’ home in 1915 at the age of 70. Harper retired from the Army in 1895 and died in 1920 at the age of 80.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Brothers in Arms: “May you live long and prosper,” 1891

In 1863, the 54th Massachusetts became the first Black regiment raised in the North. In 1891, 54th veteran Joseph J. Richardson, a successful tradesman in Chicago, purchased a copy of the new regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment and presented it as a birthday present to “my old comrade,” ex-54th corporal John W. Harper, now a sergeant major in the 25th U.S. Infantry (“Buffalo Soldiers”). Richardson added a simple heartfelt wish: “May you live long and prosper.” Richardson died in a veterans’ home in 1915 at the age of 70. Harper retired from the Army in 1895 and died in 1920 at the age of 80.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

Brothers in Arms: “May you live long and prosper,” 1891

In 1863, the 54th Massachusetts became the first Black regiment raised in the North. In 1891, 54th veteran Joseph J. Richardson, a successful tradesman in Chicago, purchased a copy of the new regimental history, A Brave Black Regiment and presented it as a birthday present to “my old comrade,” ex-54th corporal John W. Harper, now a sergeant major in the 25th U.S. Infantry (“Buffalo Soldiers”). Richardson added a simple heartfelt wish: “May you live long and prosper.” Richardson died in a veterans’ home in 1915 at the age of 70. Harper retired from the Army in 1895 and died in 1920 at the age of 80.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

A Long Friendship, 1862–1899

This 1862 Colt pocket revolver was presented to Charles R. Cox, a self-emancipated Black man from southeastern Virginia, by Robert G. Taylor, a White lieutenant of the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry. Taylor was seriously wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, Virginia, in 1862; Cox is believed to have cared for him in the hospital. In 1863, Cox and Taylor settled near each other in southwestern Pennsylvania and remained friends for the rest of their lives. Both men died on same day in 1899; Cox at the age of 100. His name is inscribed on the bottom of the grip.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

A Long Friendship, 1862–1899

This 1862 Colt pocket revolver was presented to Charles R. Cox, a self-emancipated Black man from southeastern Virginia, by Robert G. Taylor, a White lieutenant of the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry. Taylor was seriously wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, Virginia, in 1862; Cox is believed to have cared for him in the hospital. In 1863, Cox and Taylor settled near each other in southwestern Pennsylvania and remained friends for the rest of their lives. Both men died on same day in 1899; Cox at the age of 100. His name is inscribed on the bottom of the grip.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

A Long Friendship, 1862–1899

This 1862 Colt pocket revolver was presented to Charles R. Cox, a self-emancipated Black man from southeastern Virginia, by Robert G. Taylor, a White lieutenant of the 85th Pennsylvania Infantry. Taylor was seriously wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, Virginia, in 1862; Cox is believed to have cared for him in the hospital. In 1863, Cox and Taylor settled near each other in southwestern Pennsylvania and remained friends for the rest of their lives. Both men died on same day in 1899; Cox at the age of 100. His name is inscribed on the bottom of the grip.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2023

A Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in Louisiana, 1871–1874

The “L.S.M.” stamp on the trigger-guard of this rifle-musket identifies it as property of the Louisiana State Militia, a pro-Republican national guard unit comprised mainly of men of color. In 1871, the U.S. War Department issued 4,500 surplus Civil War arms to the L.S.M. to help defend the Republican governor and legislature in New Orleans from pro-Democratic “White League” paramilitary groups. This Belgian-made copy of a British Pattern 1853 rifle-musket may have been used previously by Union or Confederate forces.

DuBose Civil War Collection, 1985

A Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in Louisiana, 1871–1874

The “L.S.M.” stamp on the trigger-guard of this rifle-musket identifies it as property of the Louisiana State Militia, a pro-Republican national guard unit comprised mainly of men of color. In 1871, the U.S. War Department issued 4,500 surplus Civil War arms to the L.S.M. to help defend the Republican governor and legislature in New Orleans from pro-Democratic “White League” paramilitary groups. This Belgian-made copy of a British Pattern 1853 rifle-musket may have been used previously by Union or Confederate forces.

DuBose Civil War Collection, 1985

A Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in Louisiana, 1871–1874

The “L.S.M.” stamp on the trigger-guard of this rifle-musket identifies it as property of the Louisiana State Militia, a pro-Republican national guard unit comprised mainly of men of color. In 1871, the U.S. War Department issued 4,500 surplus Civil War arms to the L.S.M. to help defend the Republican governor and legislature in New Orleans from pro-Democratic “White League” paramilitary groups. This Belgian-made copy of a British Pattern 1853 rifle-musket may have been used previously by Union or Confederate forces.

DuBose Civil War Collection, 1985

A Breechloading Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in South Carolina, 1870–1876

The “S.C.” stamped into the buttplate of this Remington breechloading rifle-musket indicates ownership by the Black pro-Republican South Carolina State Militia. Governor Robert K. Scott, a former Union colonel and veteran of the Atlanta Campaign, obtained the guns in 1870 to defend his government against pro-Democratic paramilitary forces such as the Ku Klux Klan and, later, the “Red Shirts.” The six militiamen murdered in the Hamburg Massacre of 1876 were using these Remington arms. This example has the initials “B O” carved on the stock.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2022

A Breechloading Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in South Carolina, 1870–1876

The “S.C.” stamped into the buttplate of this Remington breechloading rifle-musket indicates ownership by the Black pro-Republican South Carolina State Militia. Governor Robert K. Scott, a former Union colonel and veteran of the Atlanta Campaign, obtained the guns in 1870 to defend his government against pro-Democratic paramilitary forces such as the Ku Klux Klan and, later, the “Red Shirts.” The six militiamen murdered in the Hamburg Massacre of 1876 were using these Remington arms. This example has the initials “B O” carved on the stock.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2022

A Breechloading Rifle-Musket Used by Black Militiamen in South Carolina, 1870–1876

The “S.C.” stamped into the buttplate of this Remington breechloading rifle-musket indicates ownership by the Black pro-Republican South Carolina State Militia. Governor Robert K. Scott, a former Union colonel and veteran of the Atlanta Campaign, obtained the guns in 1870 to defend his government against pro-Democratic paramilitary forces such as the Ku Klux Klan and, later, the “Red Shirts.” The six militiamen murdered in the Hamburg Massacre of 1876 were using these Remington arms. This example has the initials “B O” carved on the stock.

Purchase with funds from the Michael and Thalia Carlos Foundation, 2022