An aerial view of the World Trade Center collapse following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack. Surrounding buildings were heavily damaged by the debris and massive force of the falling twin towers. (Department of Defense)

After 20 years, trillions of debt-financed dollars, and tens of thousands of deaths, the war in Afghanistan is finally over. President Joe Biden recalled the U.S. military from Afghanistan on August 31, 2021. The conflict in Afghanistan is now America’s longest armed conflict, even though Congress, which has the power to declare war, never officially declared war on the nation.

When the U.S. first entered Afghanistan on Oct. 7, 2001, the country was a different place. It was reeling from the national tragedy of Sept. 11, 2001, and looking to exact revenge on those responsible—al Qaeda and the government that harbored the group, the Taliban.

Never Forget

On Sept. 11, 2001, terrorists hijacked four commercial airplanes flying over the eastern United States. The hijackers, all members of al-Qaeda, a militant Islamist organization, used the airplanes like precision-guided missiles to attack the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, major landmarks in New York City and Washington D.C.

At 8:46 a.m., the first of the four planes, American Airlines Flight 11, slammed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center in Manhattan. Less than 20 minutes later, at 9:03 a.m., a second plane, United Airlines Flight 175, struck the South Tower of the World Trade Center. People in the upper stories of the buildings were trapped as the 110-story edifices crumbled around them.

A short time later, a third aircraft, American Airlines Flight 77, struck the Pentagon, destroying the western wing of the building, which is the headquarters of the U.S. military.

At 10:03, as leaders in the U.S. began to try to make sense of the other three crashes, United Airlines Flight 93 crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers fought with hijackers and tried to regain control of the plane. It is believed the hijackers intended to fly Flight 93 into the U.S. Capitol building.

In all, nearly 3,000 people—246 passengers aboard the hijacked aircraft, 2,606 people in the Twin Towers, and 125 people in the Pentagon—died in what became known as “9/11.”

Aerial view of the Pentagon Building in Washington, D.C. on Sept. 14, 2001, showing emergency crews responding to the destruction caused when a plane crashed into the southwest corner of the building during the 9/11 terrorist attacks. (Department of Defense)

Greg Trevor, Former Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Public Information Officer

Greg Trevor is a survivor of the attacks on 9/11. Trevor, a public information officer for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, was in his office on the 68th floor of the North Tower of the World Trade Center that morning.

He came to the office earlier than usual that day, and it seemed like it was going to be a good day if the weather was any indication.

“It was one of the brightest, sunniest days,” Ihe said. “And I remember standing behind my desk, stretching my lower back. And I looked out the window and I saw the Statue of Liberty and it was glistening because it was such a bright sunny day.”

When American Airlines Flight 11 hit the North Tower, the shockwaves from the impact made the building sway and nearly knocked Trevor to the floor. He looked out of his window and saw a stunning sight.

“I saw this parabola [of] flame come past my window, and then this blizzard of paper and glass, and then silence,” he said.

Skyline of Manhattan with smoke billowing from the Twin Towers following September 11th terrorist attack on World Trade Center, New York City. (Michael Foran)

Immediately after that moment of silence, Trevor said he heard a cacophony of sirens and alarms. It was then that Trevor knew without a shadow of a doubt that something horrible had happened.

Remembering the 1993 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in which al Qaeda operatives detonated a truck bomb below the North Tower, Trevor said he immediately thought that the tremor he felt might have been from a bomb.

It wasn’t until he got a call from a local reporter that he knew that an airplane was the source of the blast.

“It made no sense,” he said. “It was a clear bright day. How could a plane have hit the building? I didn’t think at the time that it was a deliberate attack, [I] thought it was some kind of an accident.”

Once they knew that a plane had flown into the building, Trevor and his coworkers decided to evacuate, heading to the stairwell closest to them.

Because Port Authority officials mandated routine emergency evacuation drills for the World Trade Center, Trevor described the evacuation process as orderly.

There were thousands of people in the stairwells, and they proceeded down the stairs two-by-two. Unless an emergency worker needed to ascend the stairs, the line of evacuees descended at a speed of about a minute per floor.

It was while he was in the stairwell that Trevor learned from a co-worker via interactive pager that planes had also crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Just before 10 a.m., when the South Tower of the World Trade Center collapsed, Trevor said he felt rumbling and was thrust to the opposite side of the stairwell, where he hit his back. He looked up and an avalanche of dust fell into his face just before the lights in the stairwell went out. Then a cascade of water from the building’s water tanks started rushing down the stairs.

“It felt like wading through a dark, dirty river, at night, in the middle of a forest fire,” Trevor said.

As he and others reached the fourth floor, the door was blocked, and couldn’t be opened from inside the stairwell.

When word got out that the door was blocked, tensions began to rise and the relative calm of an orderly evacuation began to turn fearful.

“People were panicking,” Trevor said. “I know because you can tell from the sense of anxiety that people had. It was at that point that I thought I might not make it.”

To calm down, Trevor used breathing techniques he and his wife were taught during childbirth classes. He said a prayer, closed his eyes, and pictured his family.

“I thought to myself, their faces will keep me calm,” he said. “And if I died, they will be the last thing on my mind.”

Shortly after people began to run back up the stairs to exit the building through another stairwell, the fourth-floor door was forced open, and a port authority officer, David Lim, began shouting up the stairs, “Down is good.”

“I could hear him saying that because I wasn’t that far away. I turned around over my shoulder and yelled ‘Down is good,” said Trevor. “And then you could hear like an echo up the stairwell as people were hearing it and saying it to everybody else. And at that point, we all turned around and we all got out.”

As North Tower survivors exited the stairwell and entered the mezzanine of the World Trade Center, their evacuation route took them to an overhang. There, they were stopped by an emergency responder before being allowed to proceed.

“We had no idea why he was doing that,” said Trevor. “We did not know at that point that there were people who were jumping out of the buildings.”

Trevor and his coworkers walked around the perimeter of the World Trade Center before descending a stairwell that is now known as the “survivor staircase.” Then they began to walk uptown.

About 11 minutes later, a police officer instructed Trevor and his group to run.

“When a police officer tells you to run for your life, you listen and we started running,” he said. “This was when tower one was collapsing. And we just ran.”

A fire engine at the site of the World Trade Center collapse following the Sept. 11 terrorist attack. (Department of Defense)

Trevor and his coworkers ran for several blocks until they were about a block away from the Holland Tunnel. When they stopped running, one of Trevor’s coworkers told him that the World Trade Center was gone.

“He[said], they’re gone,” Trevor remembers. “I thought he was talking about a person or people. I said ‘who?’ He[said], ‘No, not who. The towers.’ And I turned around and looked. And the only way I can describe it was it felt like a hole in the sky.”

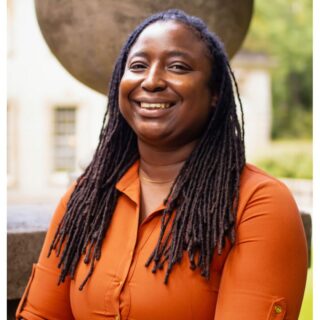

Jessica VanLanduyt, Former Atlantic Southeast Airlines Flight Attendant

Immediately after the attacks on 9/11, civilian airspace was closed. It did not reopen until Sept. 13, 2001, and Jessica VanLanduyt, a flight attendant, had to be ready to fly.

“Entering the airport was surreal,” she said. “I ran into a person I was supposed to fly with that week. And we, you know, just kind of hugged and cried. We were scared.”

Fear made her hypervigilant.

“At that point you didn’t know who was a threat. And who was ready to do something. It was still so new.”

As VanLanduyt’s fear began to subside, she and her co-workers had to relearn how to be a flight attendant in a post-9/11 world.

“Everything’s out the window at this point,” she said. “The TSA is born, so security [and] the airport changes, and [during] the first few days people are trying to figure this thing out. Airlines, the FAA, the federal government [are] figuring out what to do; they are putting out bulletins about how flights should operate. And so we kind of went through this transition period of becoming more safe over time.”

Jessica VanLanduyt poses for a photo outside of a Delta Connection aircraft. VanLanduyt was a flight attendant for the regional subsidiary of Delta before and after 9/11. (Courtesy photo)

In addition to new industry rules about how to conduct emergency operations in-flight, VanLanduyt said things changed physically in the aircraft.

Airplane doors were reinforced and cockpit doors were were replaced with bullet-proof doors to keep out threats.

One of the biggest changes to in-flight commercial air operations was that in addition to their regular duties, flight attendants became bodyguards.

“We had secret words that we used to protect the pilots; to protect the cockpit,” she said. “The pilots were protected at all costs.”

Leslie Spencer, Retired U.S. Navy Non-Commissioned Officer

Thanks to the 24-hour news cycle and cable news, most Americans watched 9/11 live on television. Leslie Spencer, a retired Navy veteran from Atlanta, was one of them. Spencer, who was an aircraft mechanic, said she would never forget where she was that day because she has a physical reminder.

“I actually have a dental reminder for life,” she said.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Spencer was in the waiting room at a Navy dental clinic. While she was waiting for the dentist, something caught her eye on the waiting room television.

“I remember the newscaster saying something about ‘We think a small plane has hit one of the towers of the World Trade Center,'” she said. “And I’m watching to try and figure out what happened, and then it says, ‘We have a report of a plane out of Boston that may have been hijacked.'”

Spencer said she knew then that the United States was under attack and that her unit would be mobilized.

“I go to the receptionist because she can’t see the TV” she said. “And I’m like, ‘Hey, we are under attack. I need to get my[dental] filming done because I know I’m not going to be around here for very long.”

A Navy airman signals the pilots of a P-3 Orion aircraft before takeoff. (Department of Defense)

Within 24 hours, Spencer and her squadron were in the air flying Navy P-3 Orion surveillance aircraft, looking and listening for pertinent information to make sense of the chaos.

Brian Stone, Retired U.S. Air Force Officer

Like Spencer, Brian Stone played a role in helping the United States military determine what happened on 9/11. Stone, a Georgia native who retired as a lieutenant colonel, flew Airborne Warning and Control System surveillance aircraft.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Stone was at Tinker Air Force Base, in Oklahoma, for a training mission. As he walked into the operations building to get a weather report, something odd got his attention.

“On the TV was the second plane hitting the second tower in New York City,” he said. “That was the one that was on live television because they had been monitoring the first strike. And we knew…we were aviators…we understood [that] on a clear day one airplane, much less two, does not fly into a skyscraper in a city. Something was going on.”

Stone and his fellow aviators received new orders to patrol U.S. airspace, making sure non-essential flights were grounded.

A page from former Air Force Lt. Col. Brian Stone’s AWACS Surveillance Log Book. (Courtesy photo)

“We were actually up there chasing down small private aircraft, ” Stone said. Small aircraft “didn’t know they weren’t allowed to fly anymore. [We had] F-16s under our control, fighter aircraft. We would vector the F-16s [to the small plane’s location], and we talked to them on GUARD (an emergency radio on both UHF and VHF frequencies) and told them, ‘You’re not allowed to fly anymore.’”

Stone said he was so busy on Sept. 11, 2001, that he missed out on the collective trauma of the day’s events.

“So, it’s interesting, when I tell the story to people, it’s like, ‘I did this great thing that day,’” he said. “I was over my country, but I missed that whole day. People stayed in front of the television all day and absorbed these stories. I didn’t see it happen live on TV. It all came to me as a story.”

A month after 9/11, as part of the Global War on Terror, President George W. Bush announced Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), beginning a 20-year occupation of Afghanistan. The purpose of the invasion, according to the U.S. government, was to root out the mastermind of the attacks, Osama bin Laden, and destroy al-Qaeda strongholds in the country.

Bin Laden greenlit the attacks on the U.S. as a counterprotest of sorts. He opposed U.S. support of Israel, wanted to retaliate for the first war in the Persian Gulf, and hated the U.S. presence in the Middle East.

Both Spencer and Stone supported OEF missions in the war on Afghanistan.

In March 2003, U.S. forces captured Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, bin Laden’s co-conspirator, and took him to a U.S. detention facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where he remains to this day.

Around the same time that the U.S. captured Mohammad, President Bush, convinced that Iraq was an al-Qaeda stronghold that had weapons of mass destruction, authorized Operation Iraqi Freedom, an invasion of Iraq.

Michael Schlitz, Retired U.S. Army Ranger

Michael Schlitz was one of the soldiers sent to fight in Iraq. The Army veteran from Illinois joined the military because he was “kind of floating through life at the time,” and did not really know what he wanted to do with his life. His father and his brother were both veterans, so Schlitz decided to join the military as well. Though slight of stature at 5 foot 6, he became an Army Ranger, one of the Army’s elite soldiers, who are typically tasked with special operations duties. Schlitz and his unit deployed to Iraq in August 2006 as part of a U.S. troop surge in the country.

Their job in Iraq mostly consisted of patrolling and capturing ground in the Sunni Triangle on the Southwest side of Baghdad. According to Schlitz, the area was appropriately nicknamed the “Triangle of Death” because it was notorious for improvised explosive devices and ambushes.

Though Schlitz knew the hazards of his job, he performed it dutifully until Feb. 27, 2007. Schlitz said that day started off normally, but things changed when he and his platoon had to double back down a path on which they had previously traveled.

“Typically, when you plan your route, you never cover the same spot more than once because if you do, you get blown up because they can predict you,” he said. “Unfortunately, with a dead-end road, there’s one way down, [and] one way back.”

Although Schlitz and his fellow soldiers took their time going back across the road, his fears came true when he heard an explosion.

“I can remember hearing the boom. And before I could even get a choice four-letter word out, I’m hitting the ground,” he said. “I can remember hitting my head and my shoulder on the ground when I got thrown from the vehicle.”

Schlitz realized that he was on fire.

“They always say your life flashes in front of you. I really didn’t have that, but I definitely was like, ‘Okay. This is it for me. This is where my life ends. I’m going to die here face down in the ground in Iraq. What am I going to do? I can’t move. I’m on fire.”

Retired U.S. Army Ranger Michael Schlitz, a veteran who was burned over 85 percent of his body by an IED, speaks to soldiers at Al Asad Air Base, Iraq about suicide prevention. (Department of Defense)

Quick thinking from members of Schlitz’s platoon saved his life. He was taken to a medical facility in Belat and then airlifted to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany. He was later transported to Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas, where he spent more than 10 months in the hospital, six of them in intensive care where he endured multiple skin grafts and reconstructive surgeries.

When Schlitz left the hospital, he bore the scars of the war in Iraq. His hands were amputated; his torso and face were badly scarred; and he was deeply depressed. He considered ending his life, but the people who rallied behind him during his ordeal helped him find the will to live.

The “Tribute in Light” memorial in remembrance of the events of Sept. 11, 2001, in honor of the citizens who lost their lives in the World Trade Center attacks. The two towers of light are composed of two banks of high wattage spotlights that point straight up from a lot next to Ground Zero. (Department of Defense)

Where are They Now?

Though the terrorist attacks on 9/11, the deadliest terror attack in U.S. history, disrupted the lives of many Americans, it is a thread that binds Trevor, Van Landuyt, Spencer, Stone, and Schlitz. And instead of letting tragedy overwhelm them, all have gone on to do even greater work for the public good.

Trevor, who moved to Georgia in 2016, is now the associate vice president of Marketing and Communications at the University of Georgia. He is also an advocate for mental health and speaks to people about the importance of destigmatizing mental illness.

Van Landuyt went back to college and obtained her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. She was hired here at Atlanta History Center in 2007, resigned from Atlantic Southeast Airlines, and left her career as a flight attendant behind. She currently serves as the senior vice president of Guest Experiences at AHC.

Towards the end of her career in the Navy, Spencer became a recruiter, where she helped directionless young people find purpose in the armed forces. After she retired from the Navy, she went back to school to pursue her passion for history. She is currently pursuing a doctorate in historic preservation at Georgia State University.

Stone retired from the military in 2012, moved back to Georgia, and went to work for Operation Military Kids, a Department of Defense-sponsored camp for the children of deployed service members. Operation Military Kids showed Stone that he had a gift for working with kids and he now works at Summer Academy, an organization that hosts academic summer camps.

Schlitz, after his medical retirement from the Army, became a public speaker and advocate for those who suffered physical and mental injuries in the military. He travels all over the country, inspiring and motivating people.

He returned to Iraq with a program called “Operation Proper Exit” to see where he was injured and how the country has changed for the better.