As a cultural institution in one of the most diverse cities in the country, Atlanta History Center recognizes our responsibility to use our tools and platforms to center stories of communities not often given the space to do so. The need to both collect and preserve these stories as well as to share them was underscored in the wake of the murder of eight people in Metro Atlanta on March 16, 2021, including seven members of the Asian American community.

In line with this imperative, we’re asking members of the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community to consider sharing stories, photographs, signs of protest, and presence with us. In doing so, we can come together to tell a more complete history of our city. Please get in touch with our Museum Collections team to share your stories.

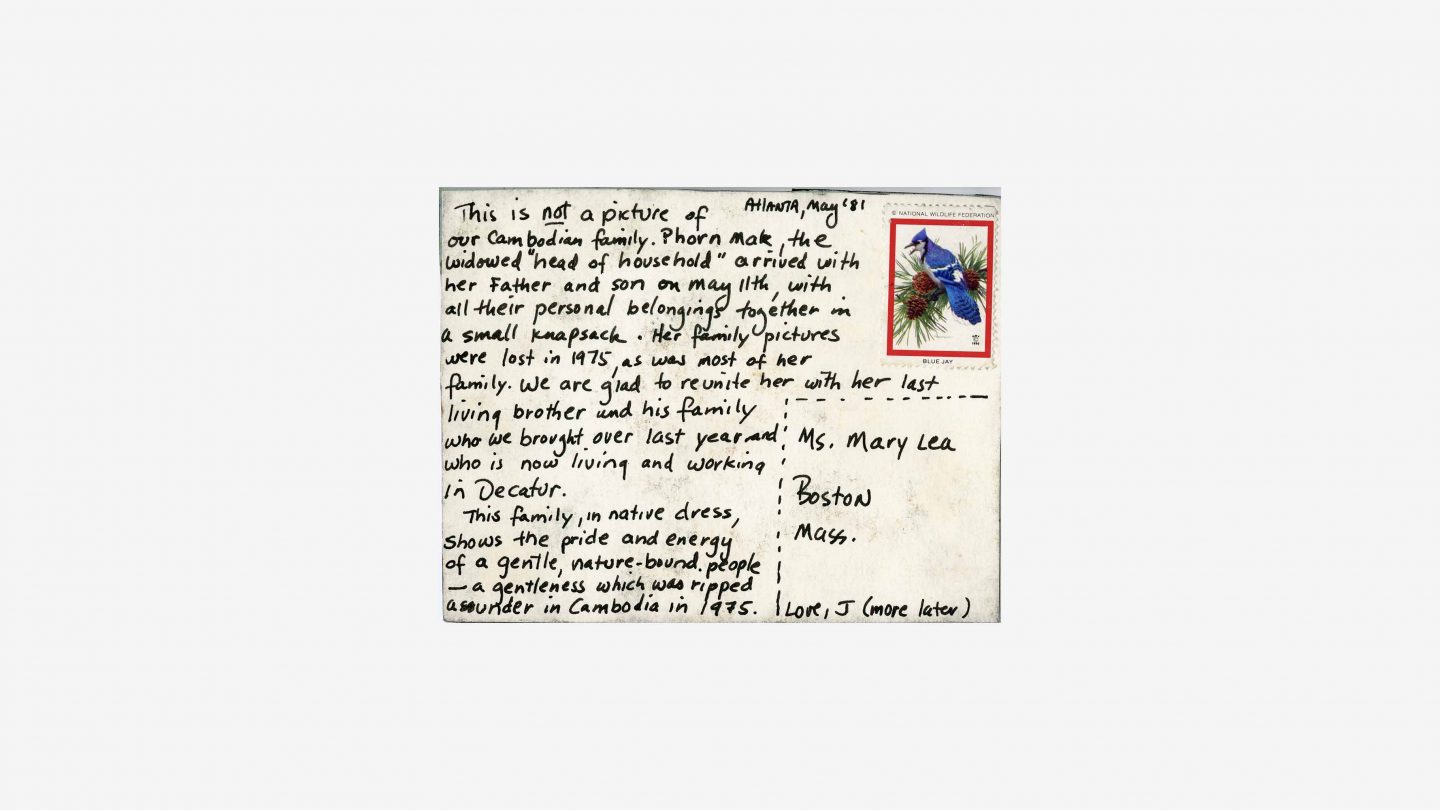

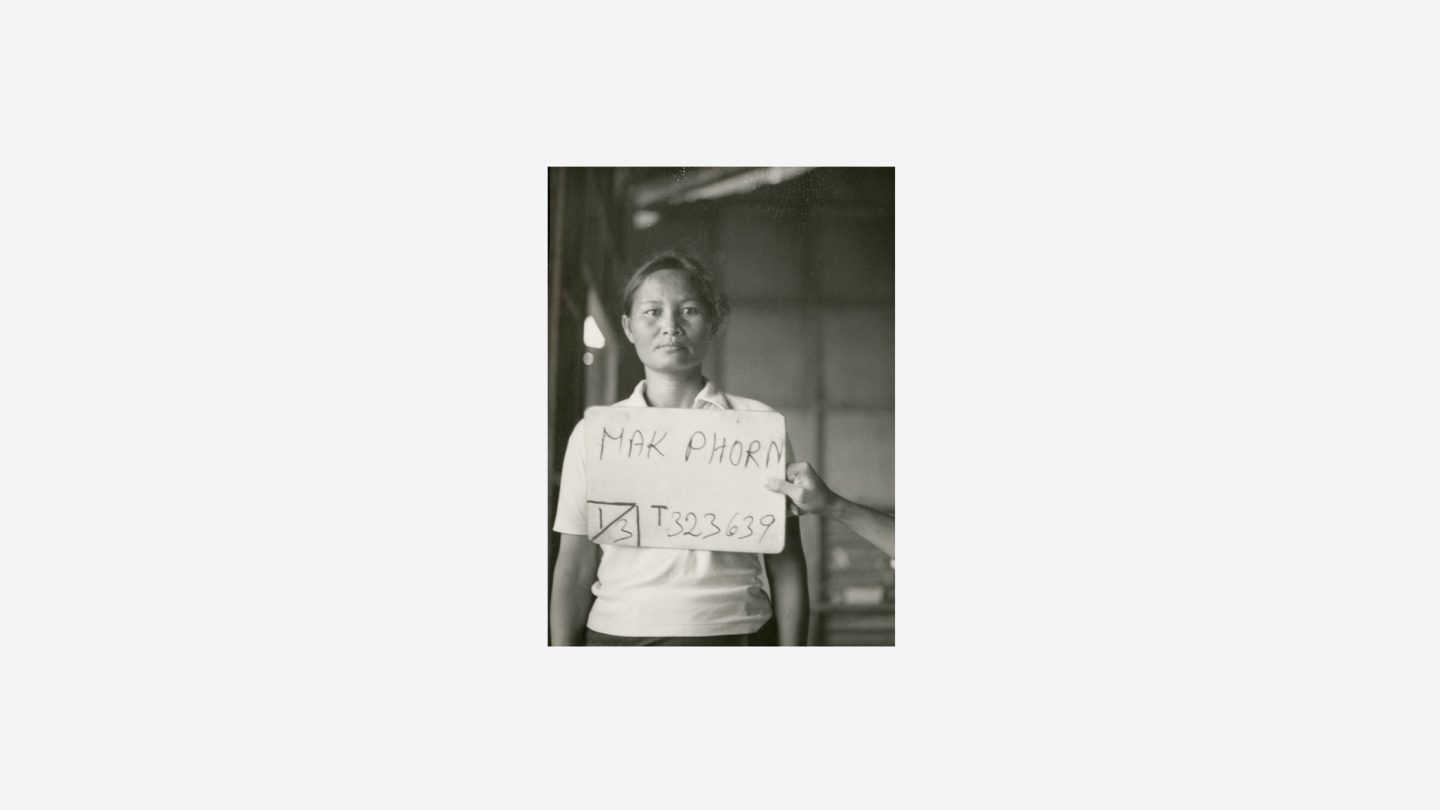

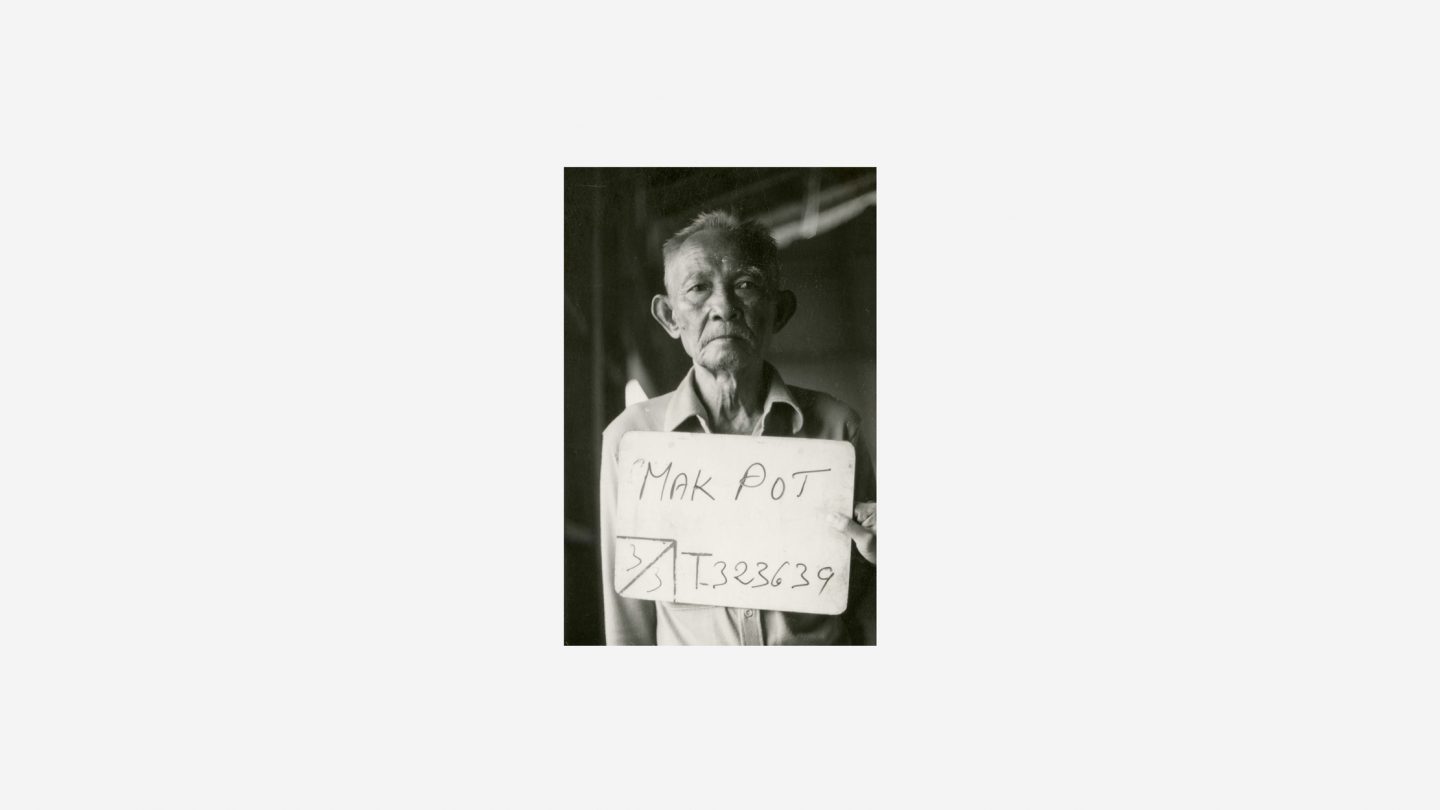

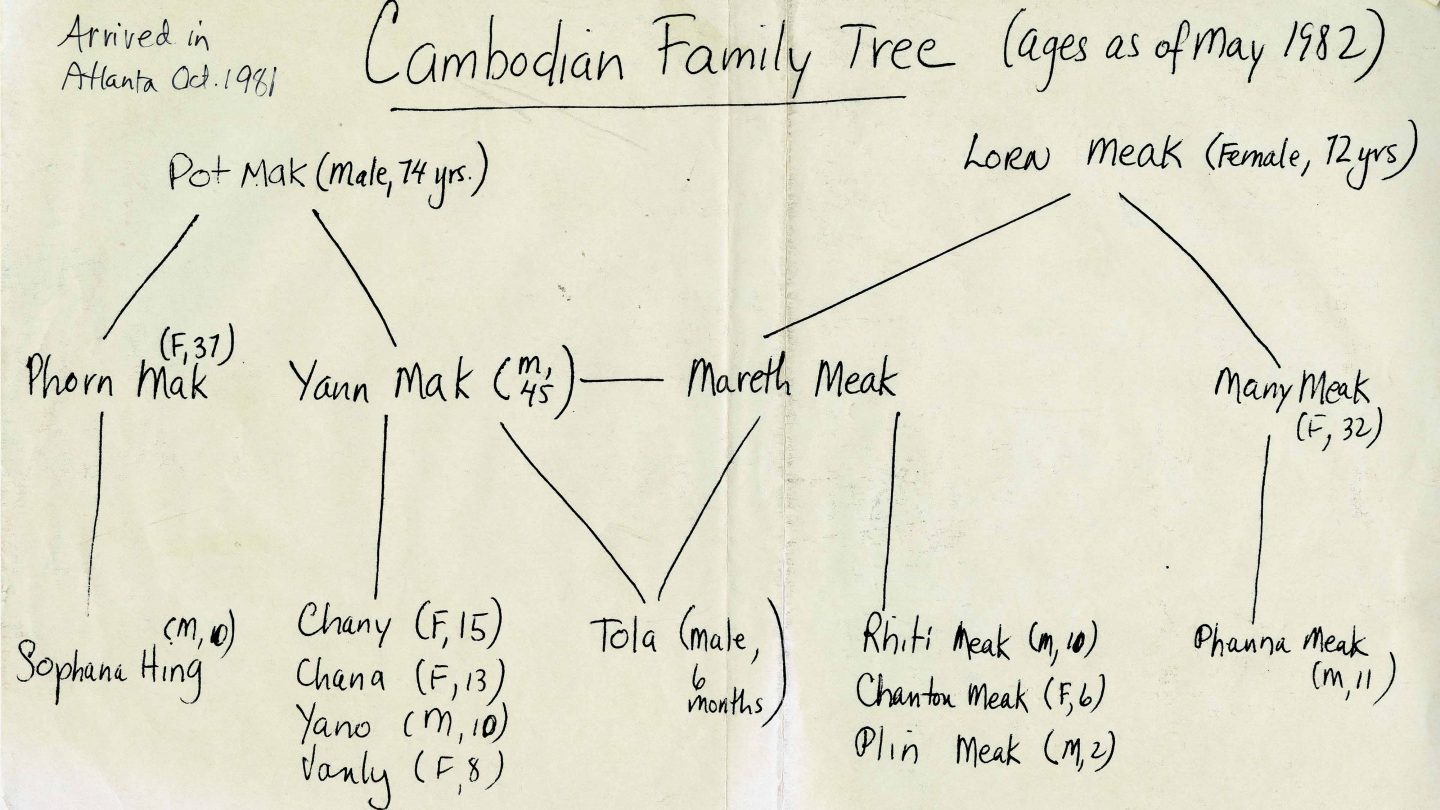

Yann and Mareth Mak and their eight children arrived in Atlanta in October 1981 with their lives and little else.

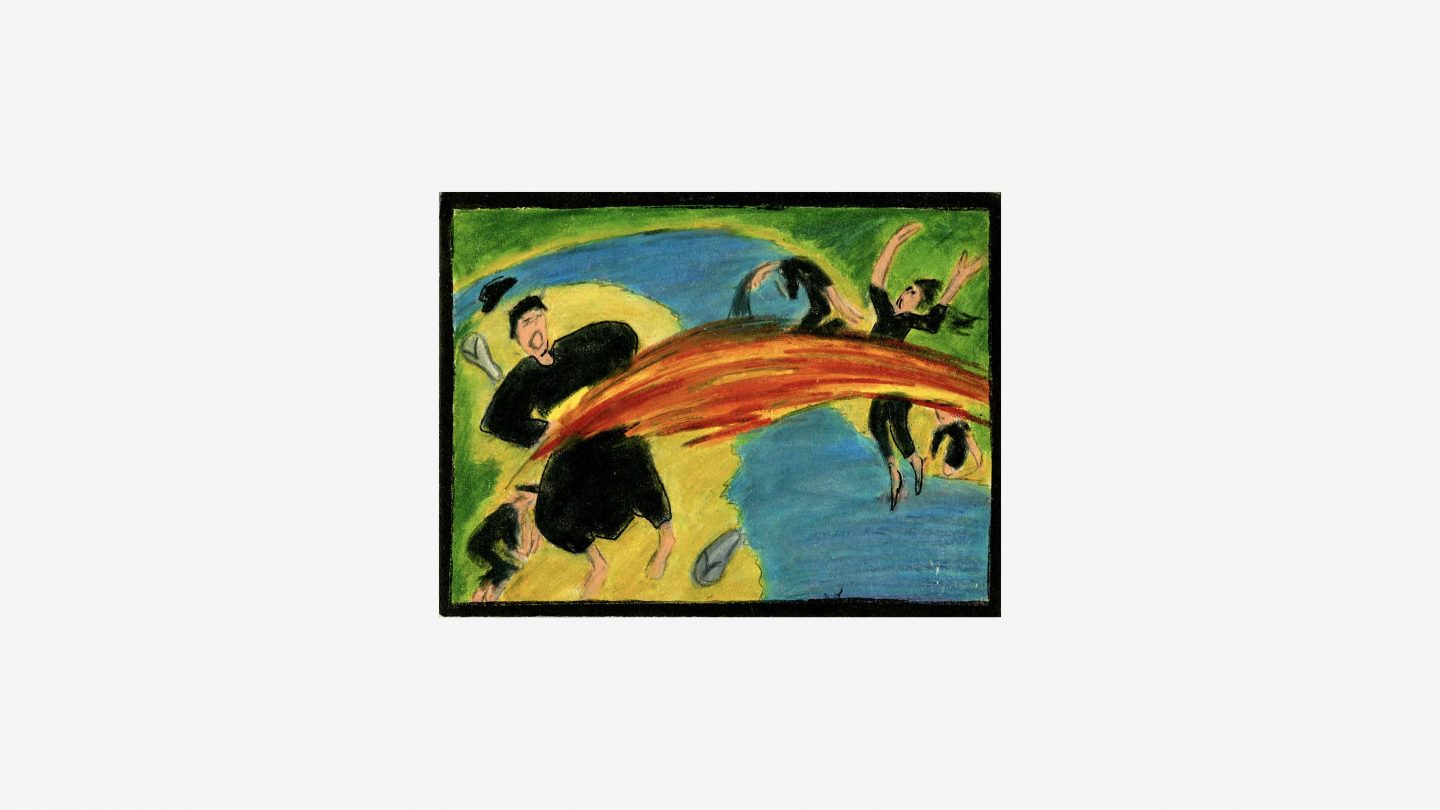

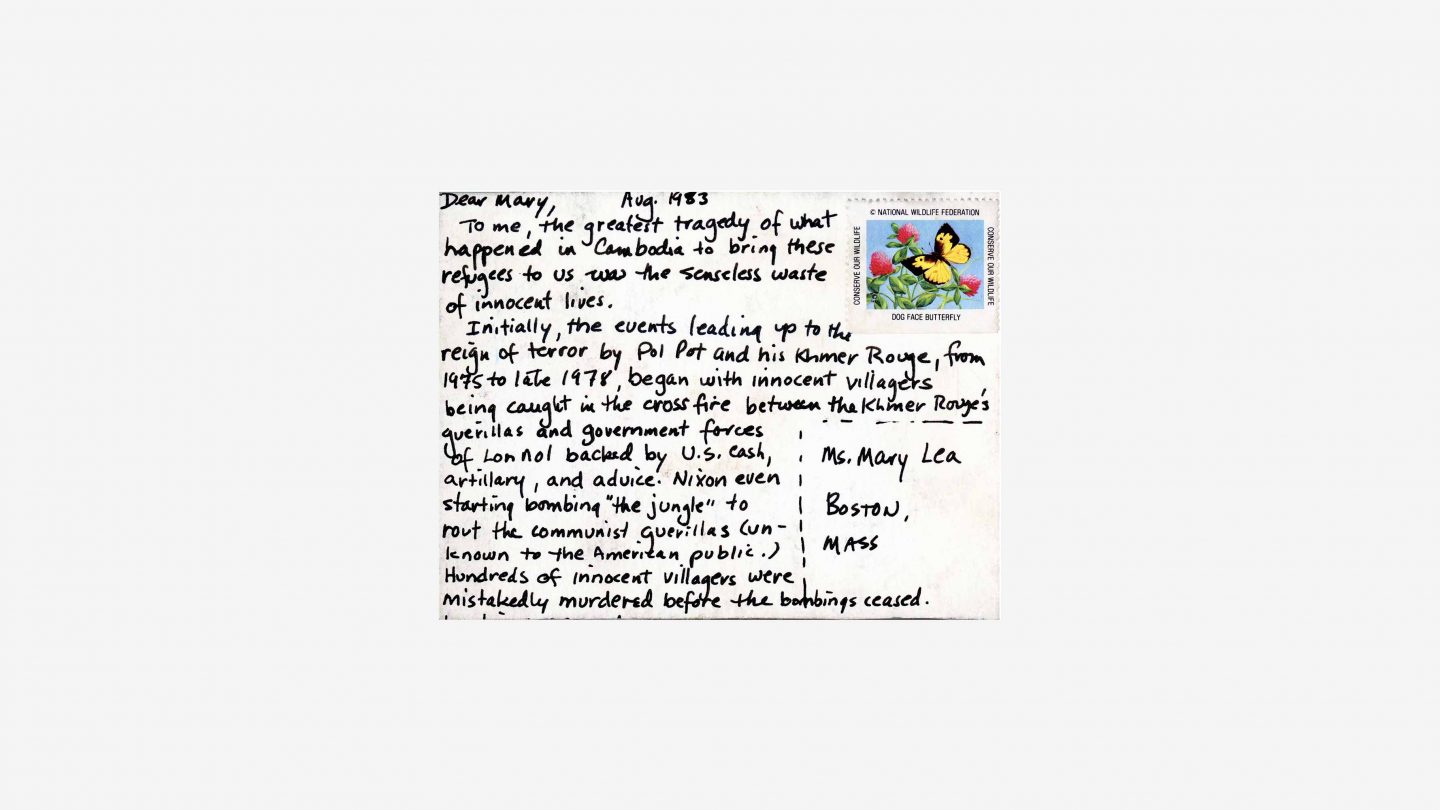

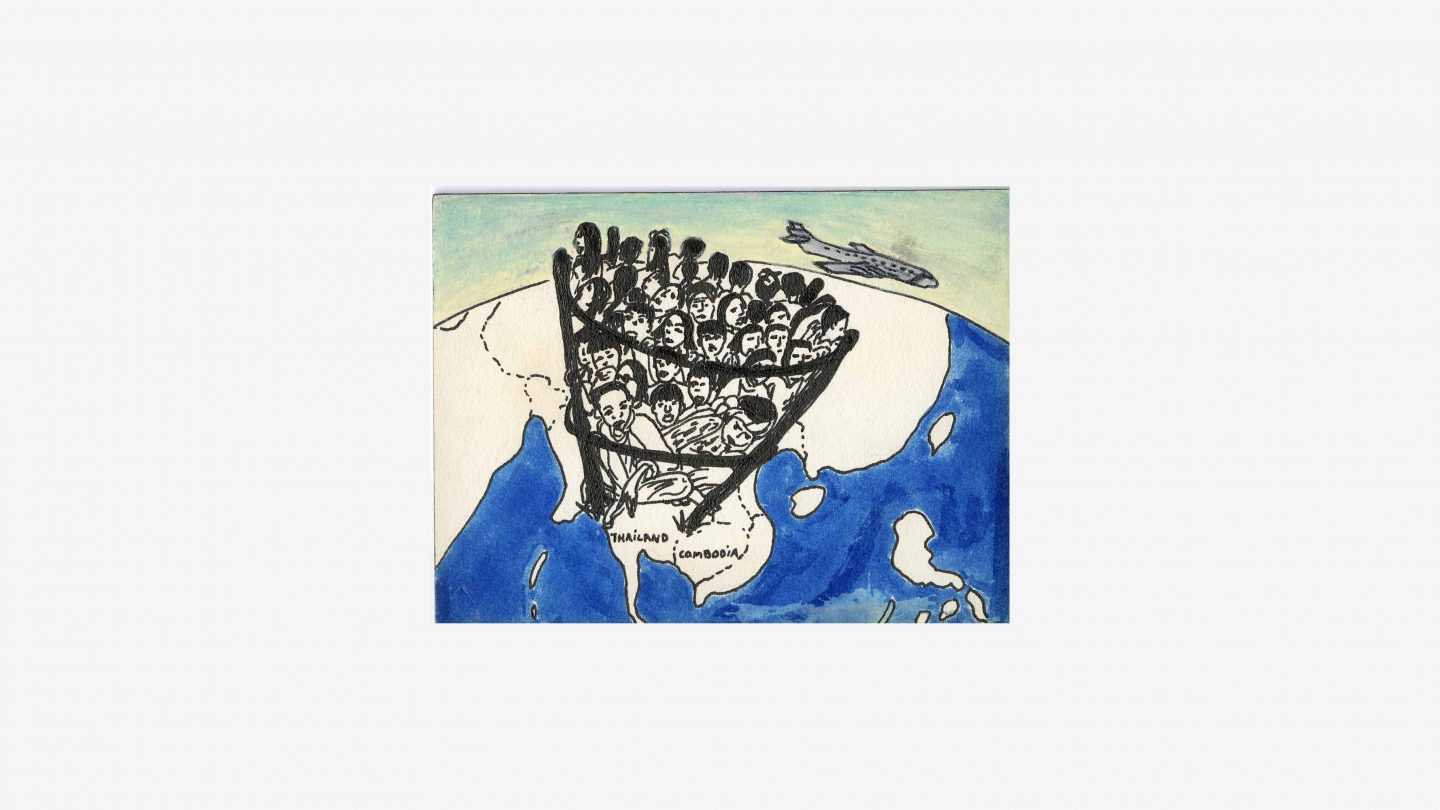

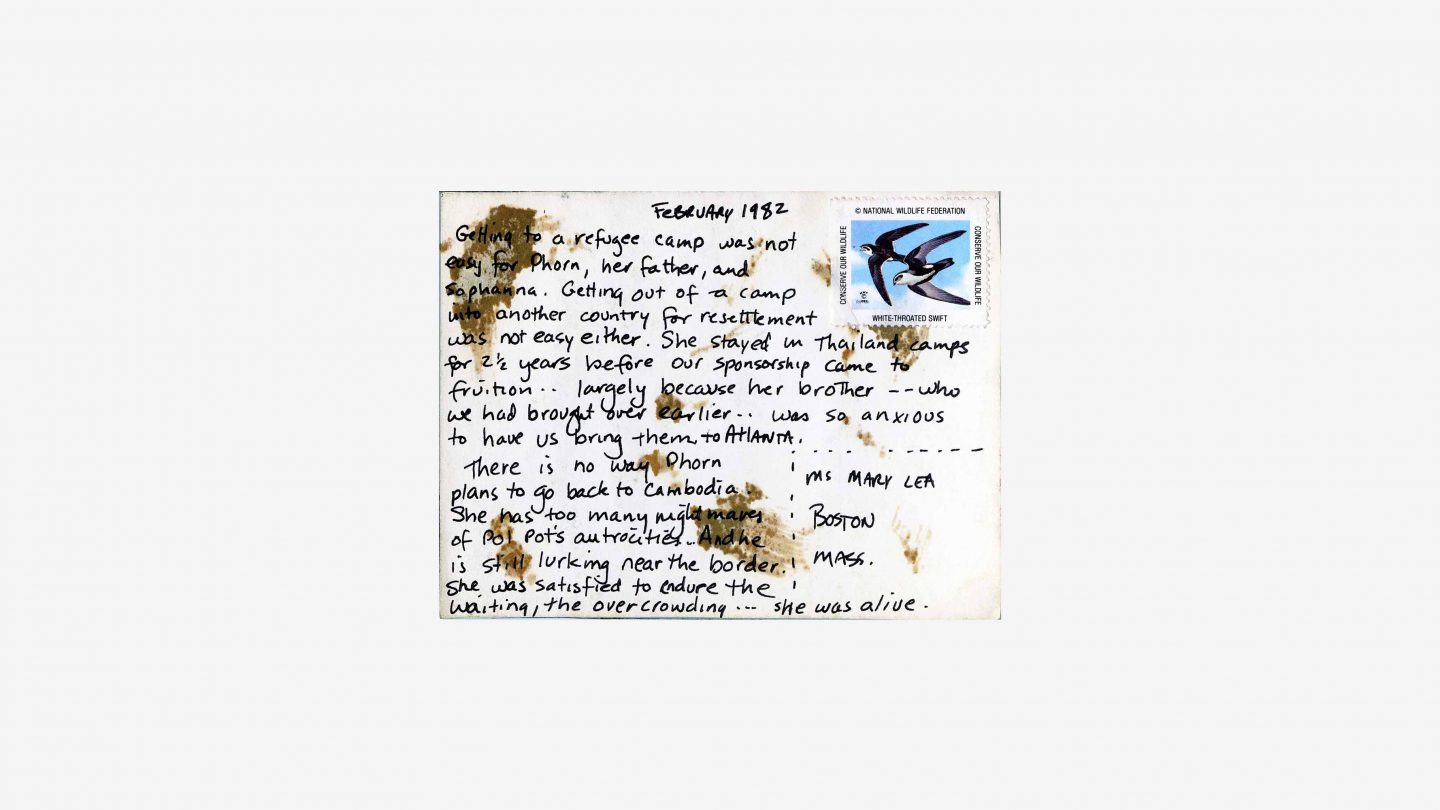

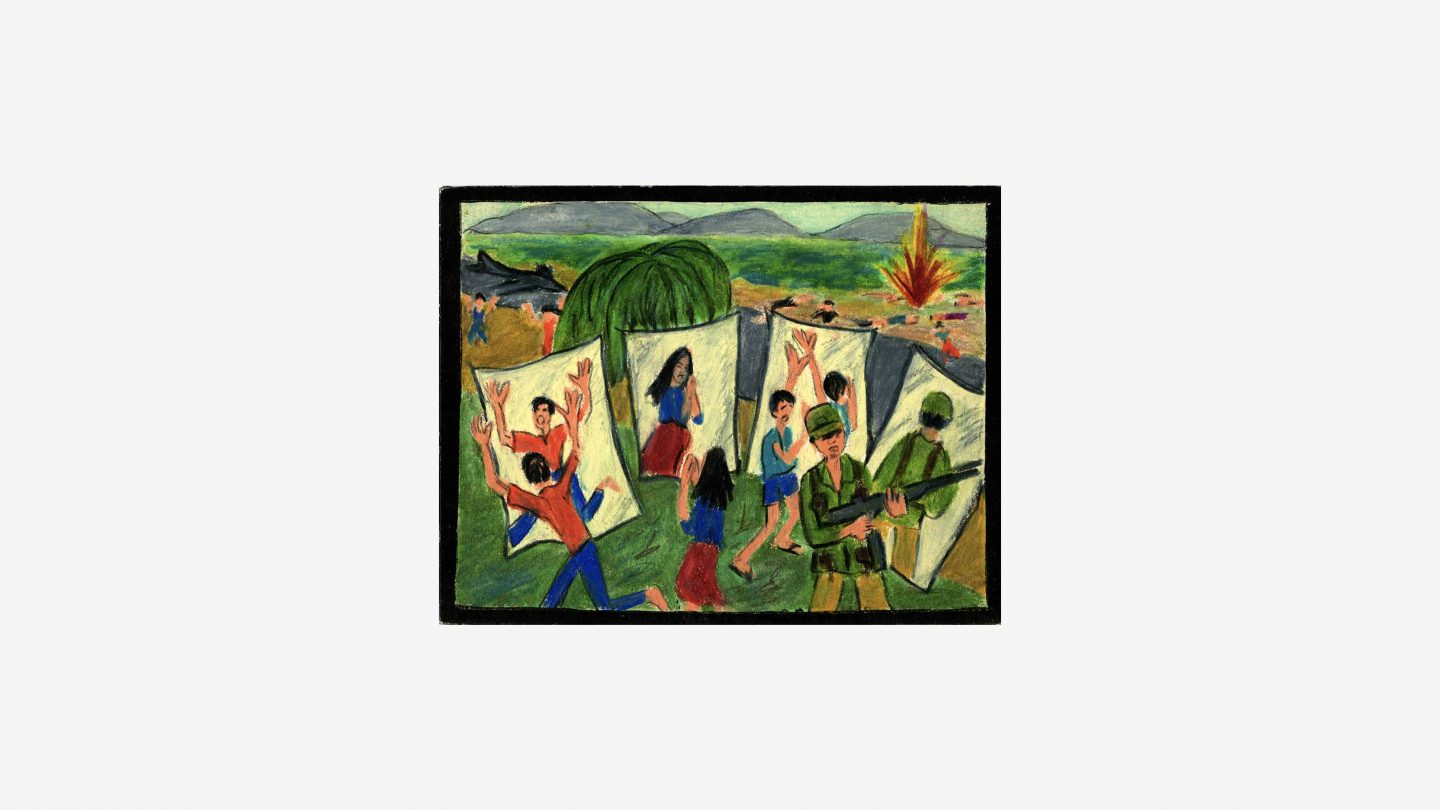

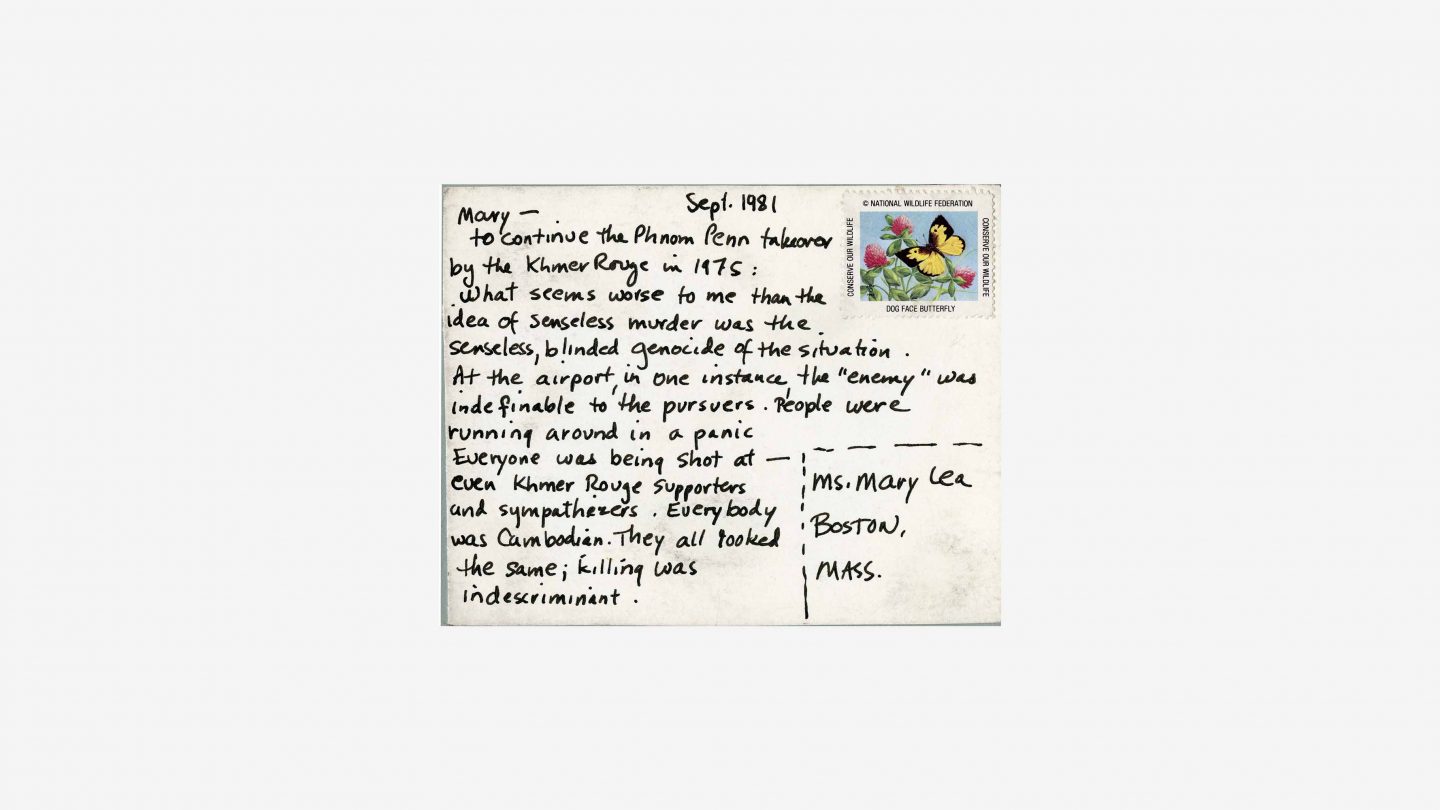

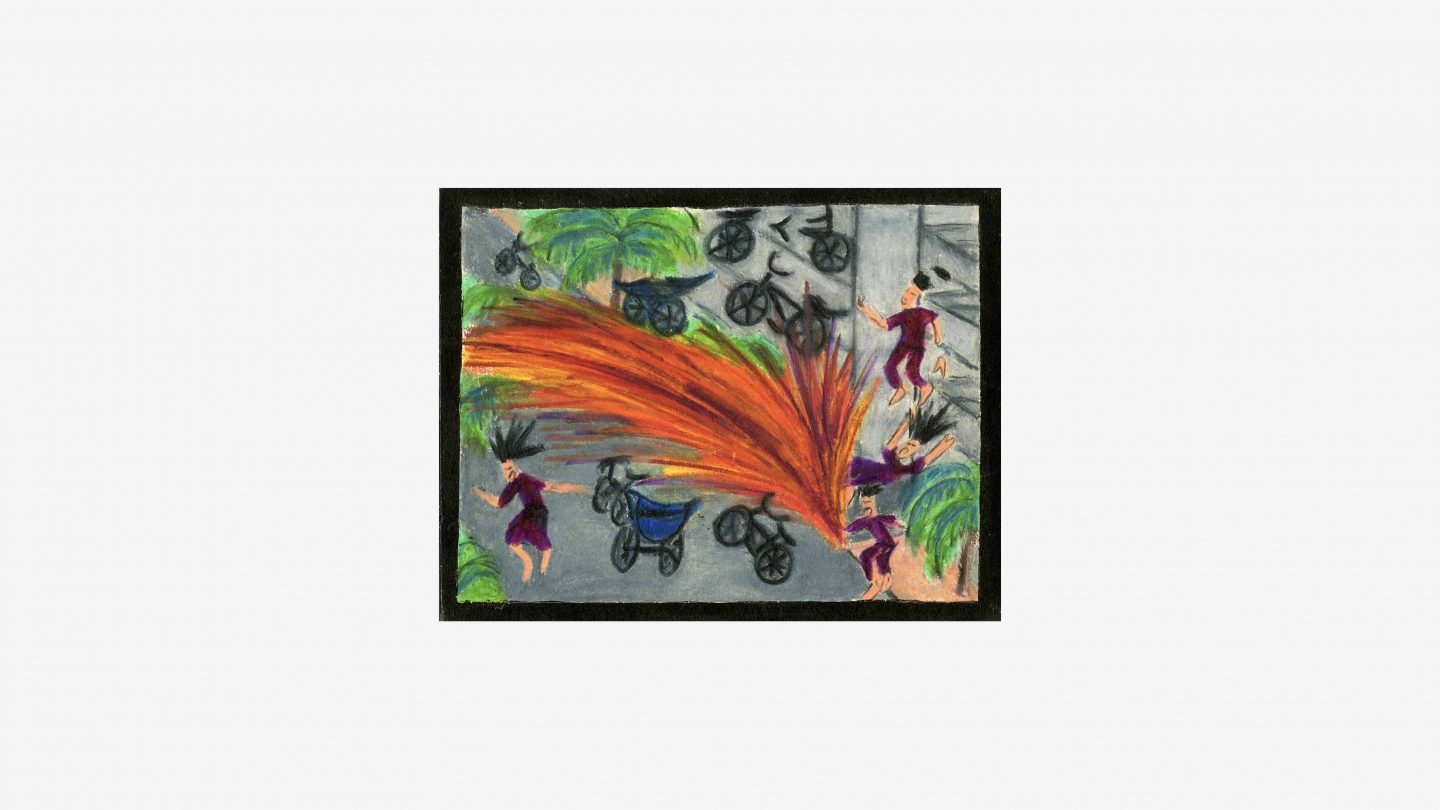

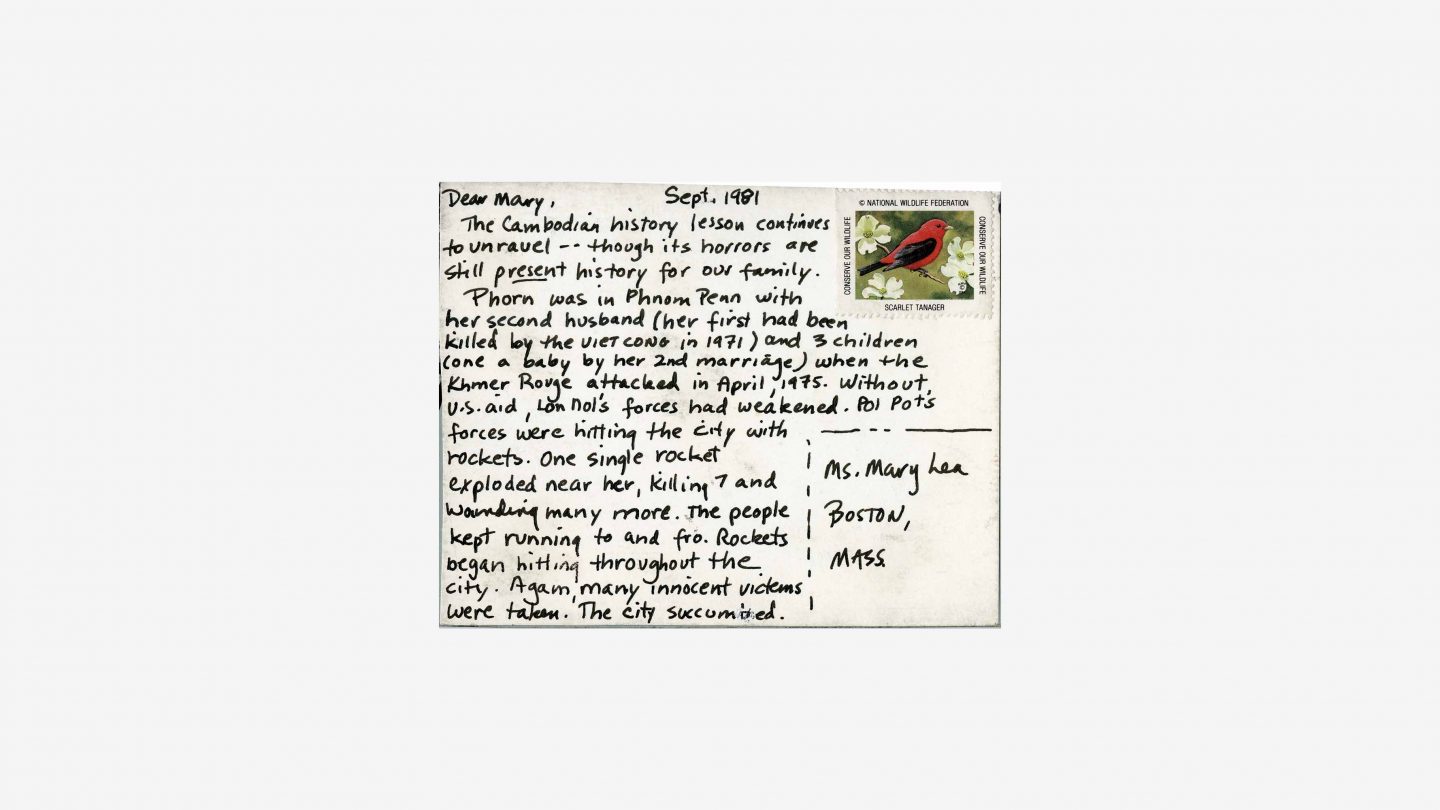

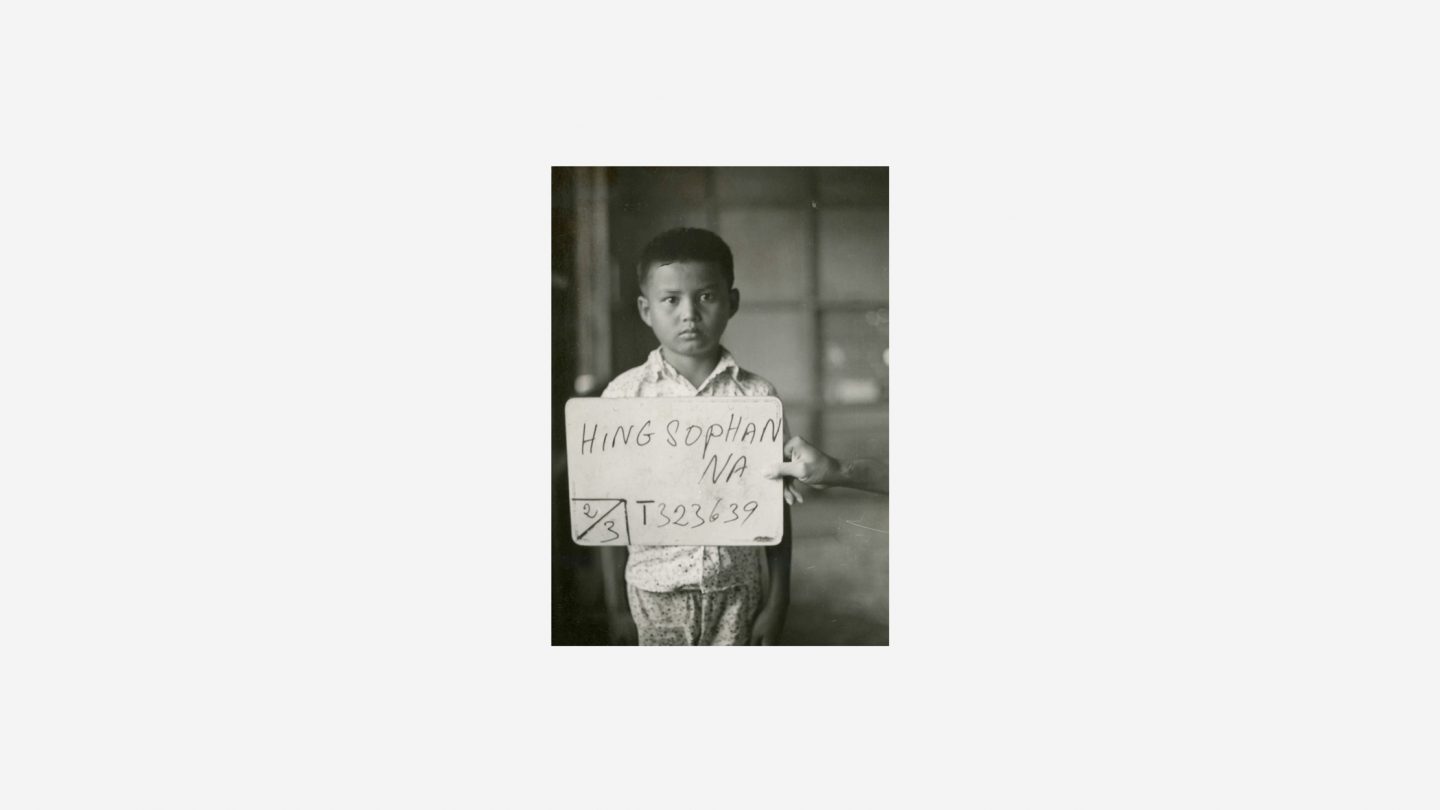

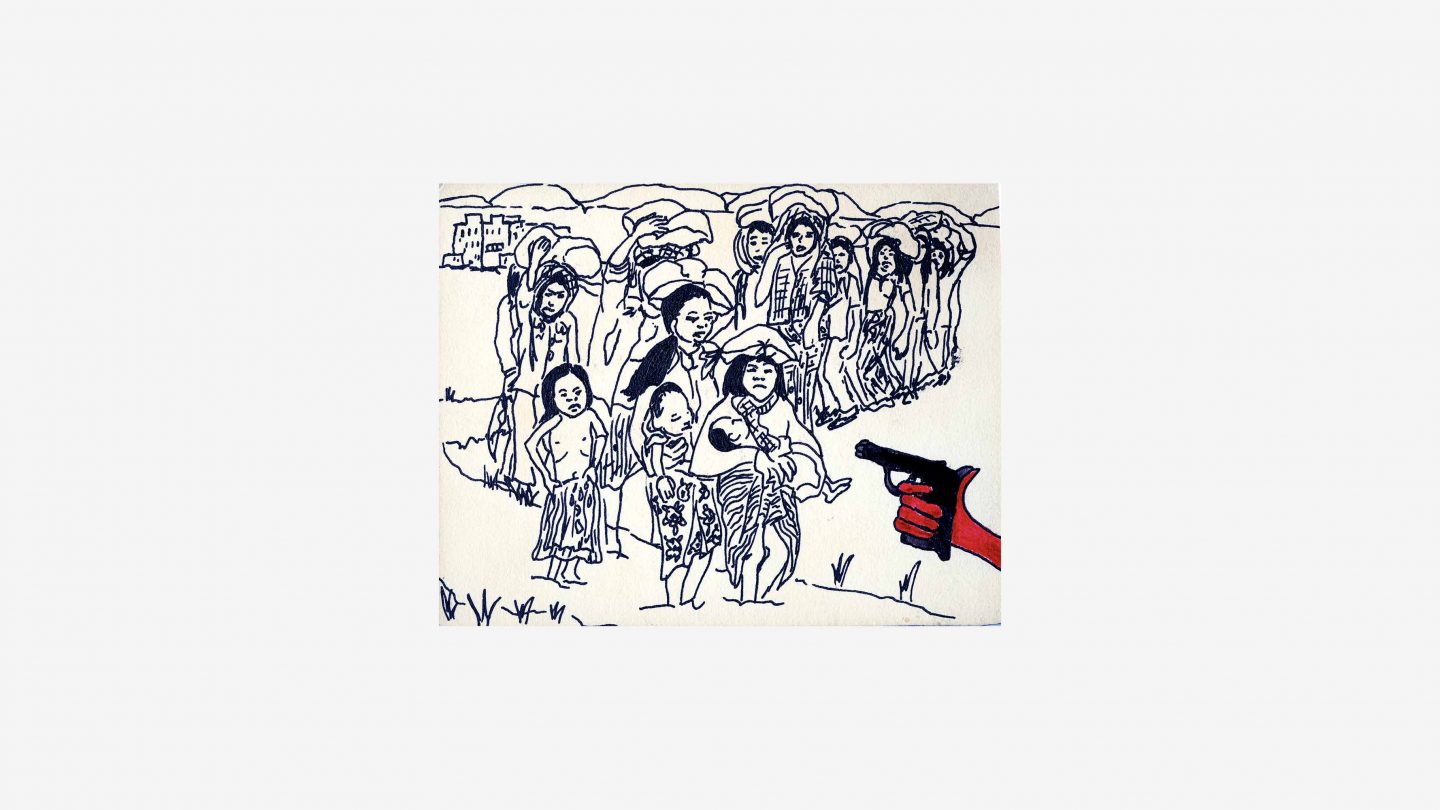

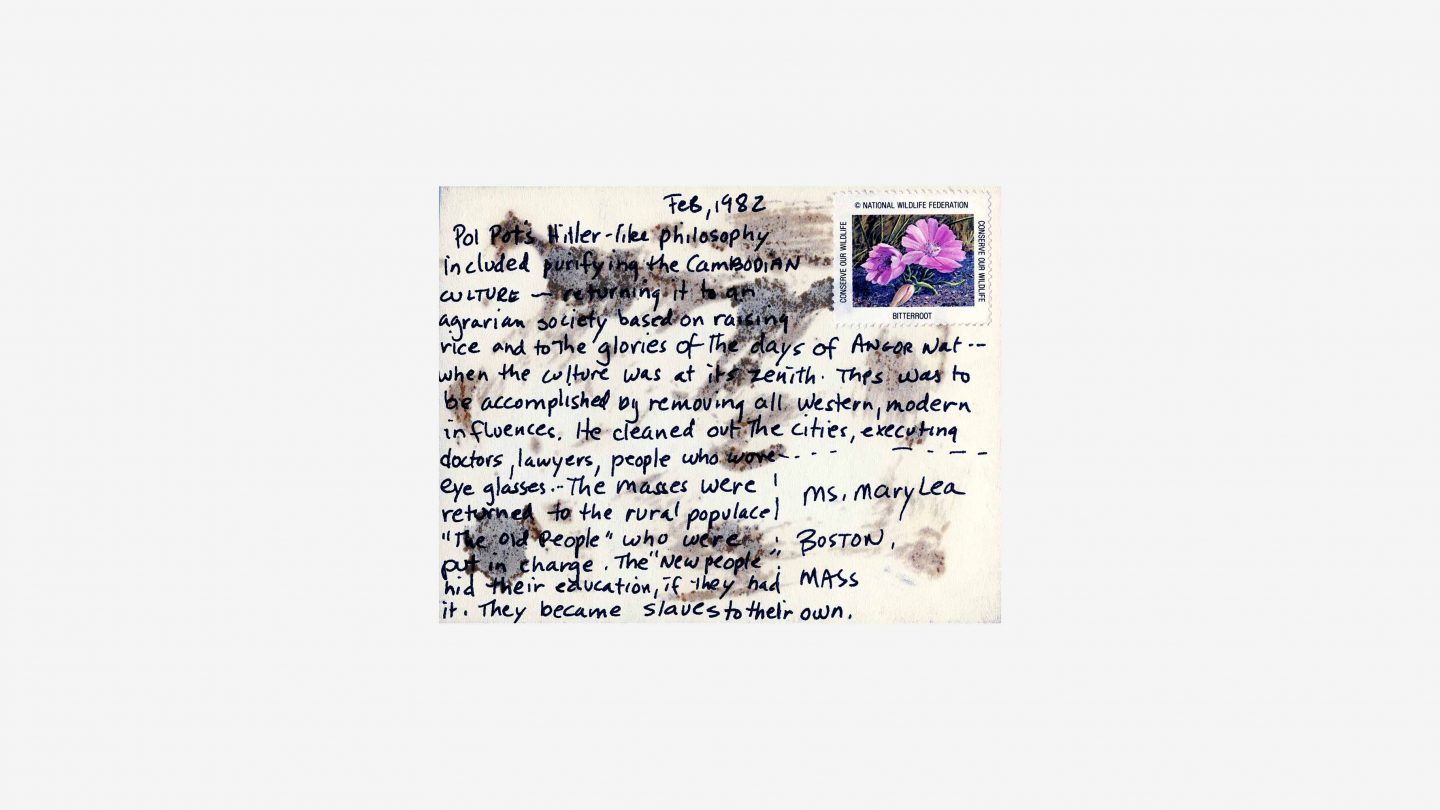

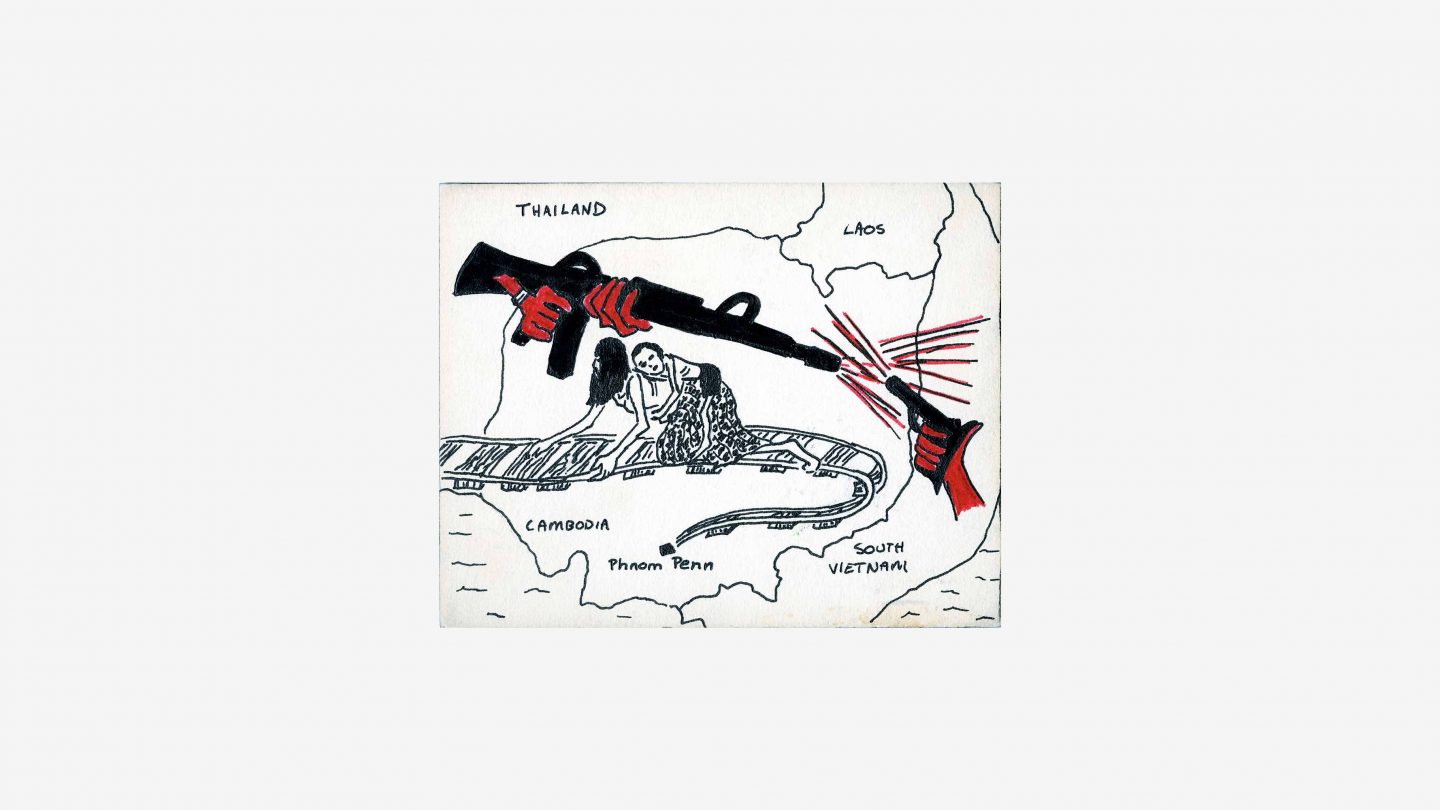

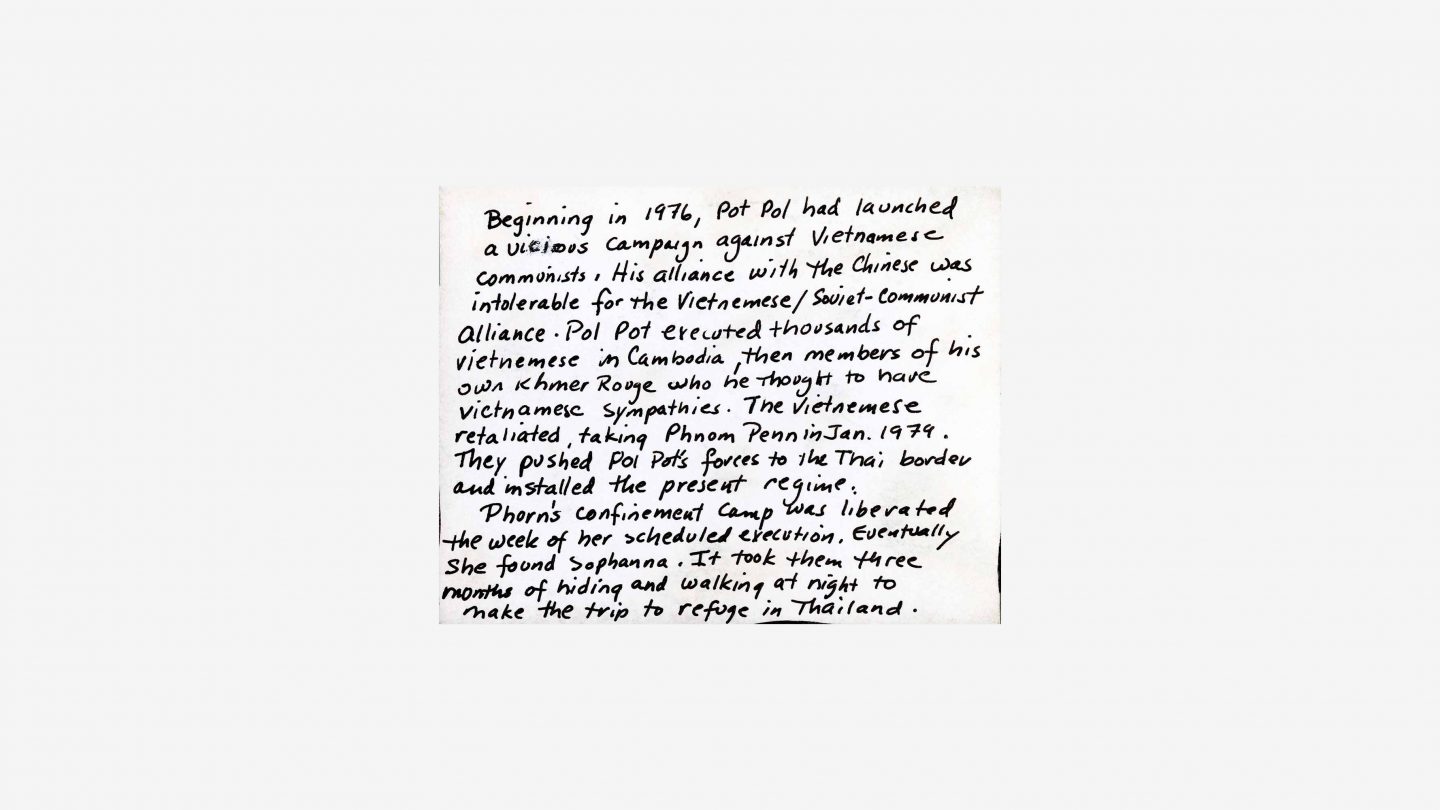

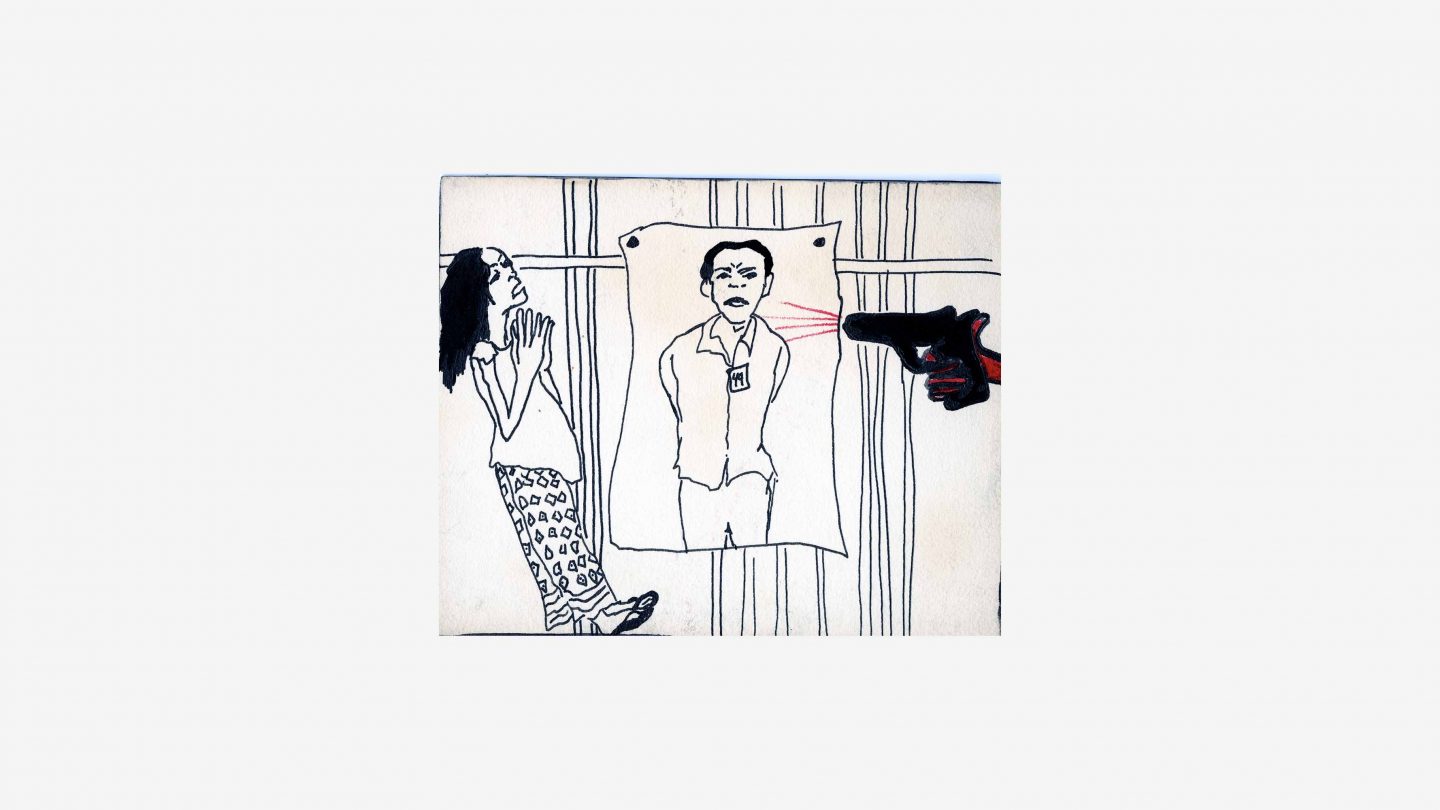

The couple and their eight children (including seven from previous marriages) escaped their native Cambodia and the acts of genocide carried out by Khmer Rouge. The Maks fled to refugee camps in Thailand, where they spent two years under constant fear of death before receiving permission to relocate to the United States in DeKalb County, Georgia.

The Mak family’s story is just one of the thousands that make up our city’s refugee tapestry.

In Georgia, Asians comprise more than 4% of the population, up from less than 1/2% in 1980. According to census data, the foreign-born population of Atlanta grew rapidly between 1970-1990. While the number of European-born immigrants minimally increased, the Asian-born population expanded exponentially from 10,000 in 1970 to 72,000 in 1990.

Historically, the US Census has consistently underreported non-white populations, so there is also a fragment of the distinct AAPI communities that was likely not captured by these totals.

By 1990, one out of every 41 Georgians was foreign-born.

As Atlanta’s white population relocated to the suburbs beginning in the 1960s, immigrant communities have filled the inner-perimeter gaps left behind.

In October 1981, the Mak family found themselves in stark contrast to other passengers disembarking at Hartsfield International Airport. They all suffered from malnutrition. Eight-year-old Vanly weighed just 36 pounds when she arrived at Hartsfield. Only some of the children wore shoes; the clothes on their back were all they brought with them. Yann clutched the family’s only luggage, a small bag containing a scant few pictures and keepsakes of their lives in Cambodia.

The group who sponsored the Mak family’s relocation was the East Atlanta Refugee Sponsors (EARS). EARS comprised three original member churches: Holy Trinity, St. Bede’s Episcopal, and Church of the Epiphany. After it was discovered that Eastminster Presbyterian already sponsored the relocation of Mareth’s mother, sister, and nephew, they formally joined as a fourth church.

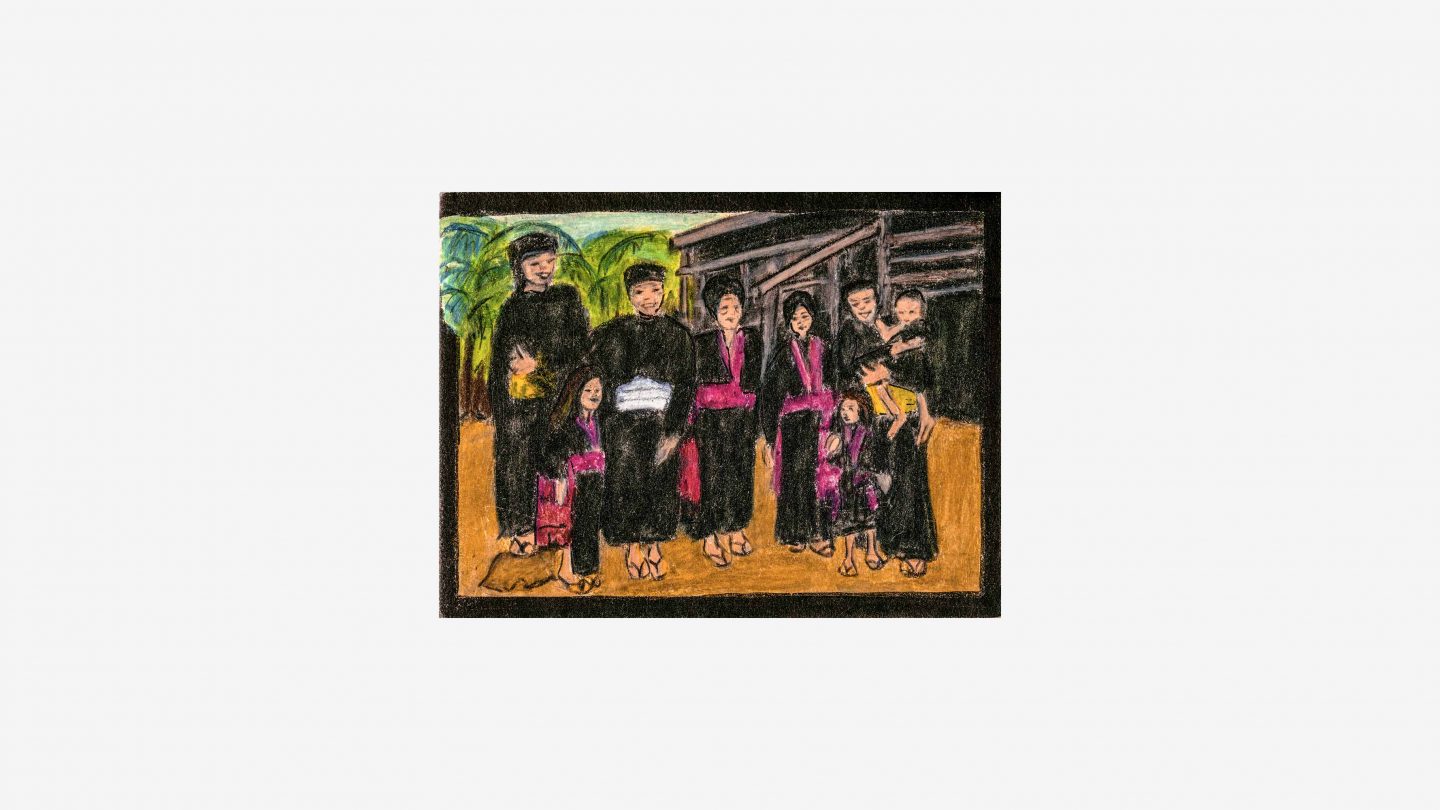

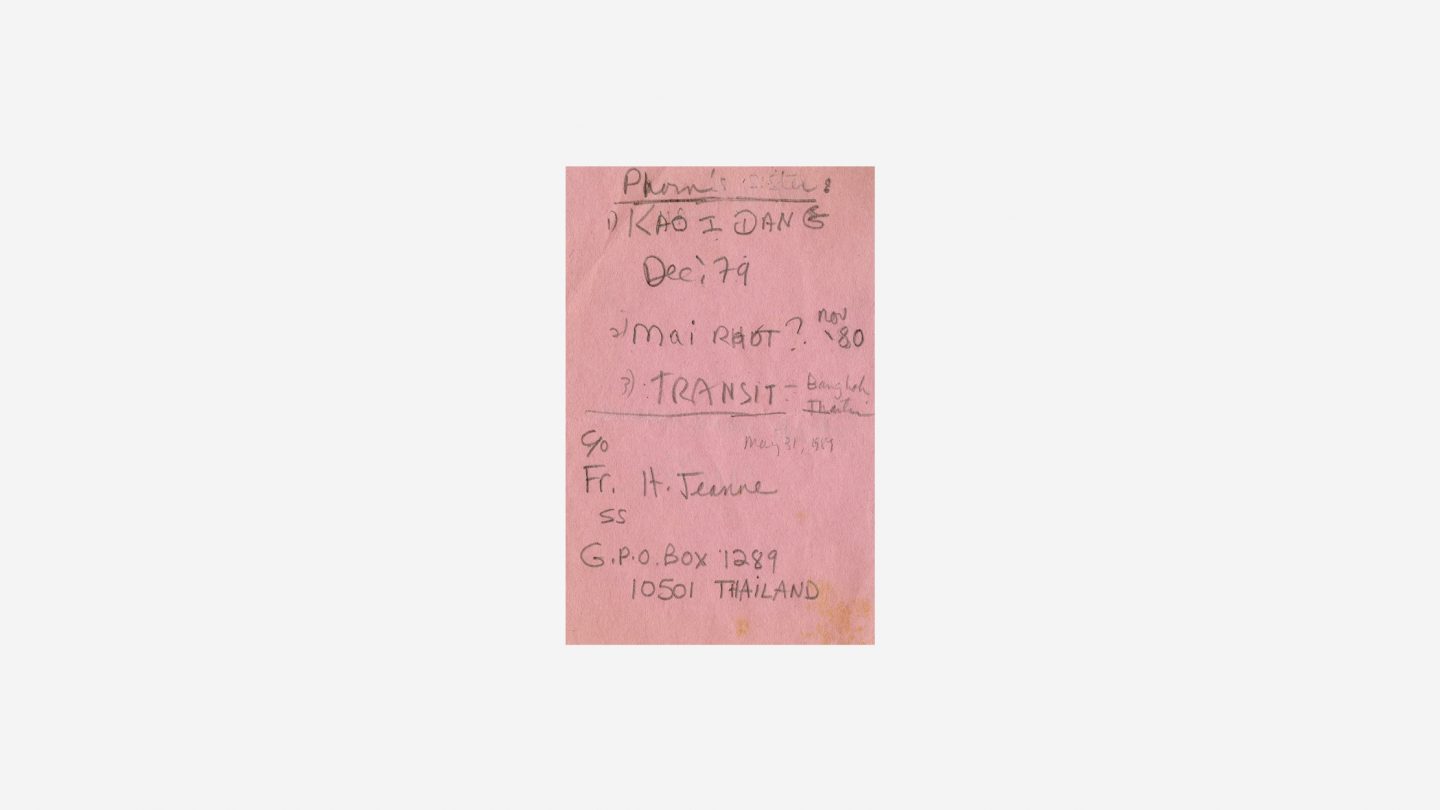

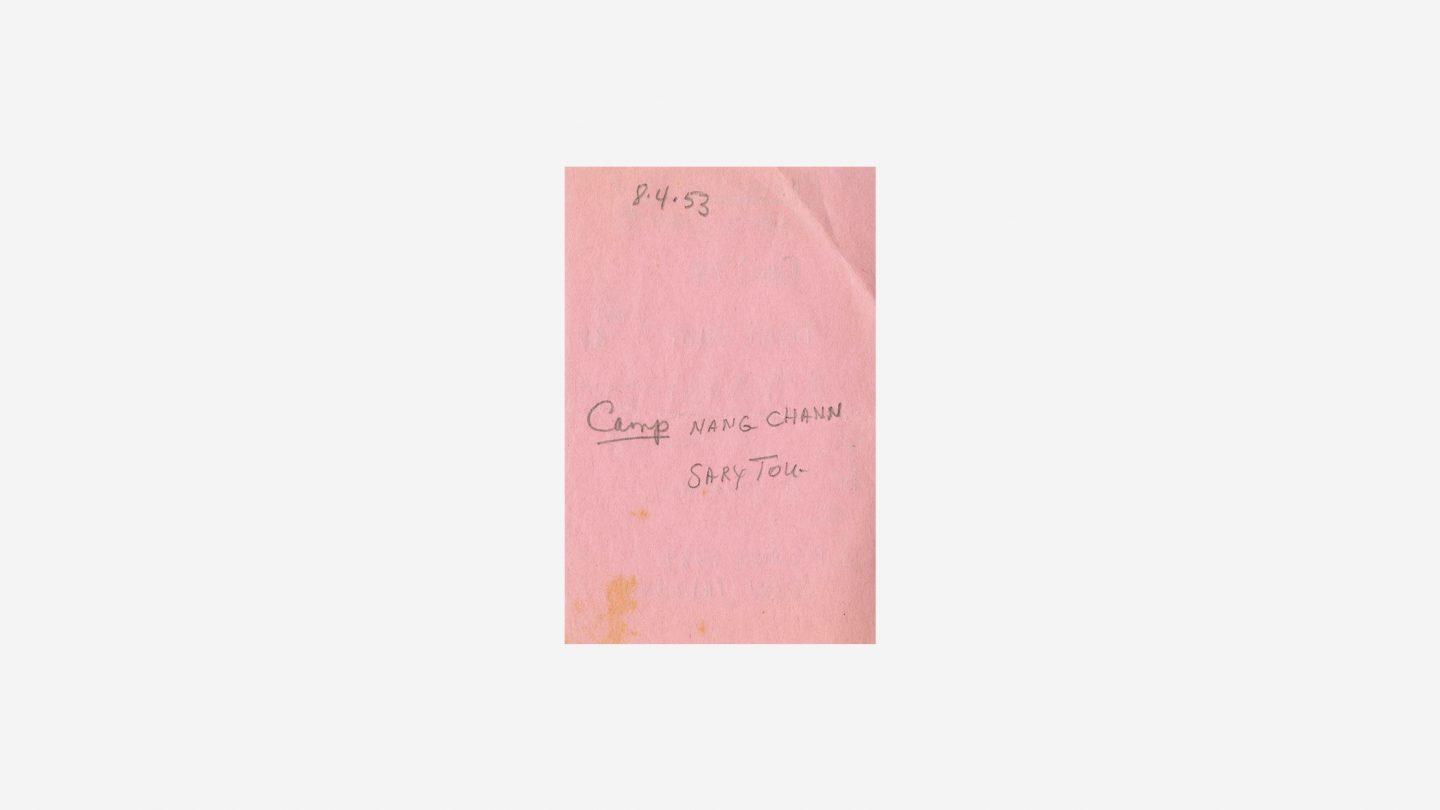

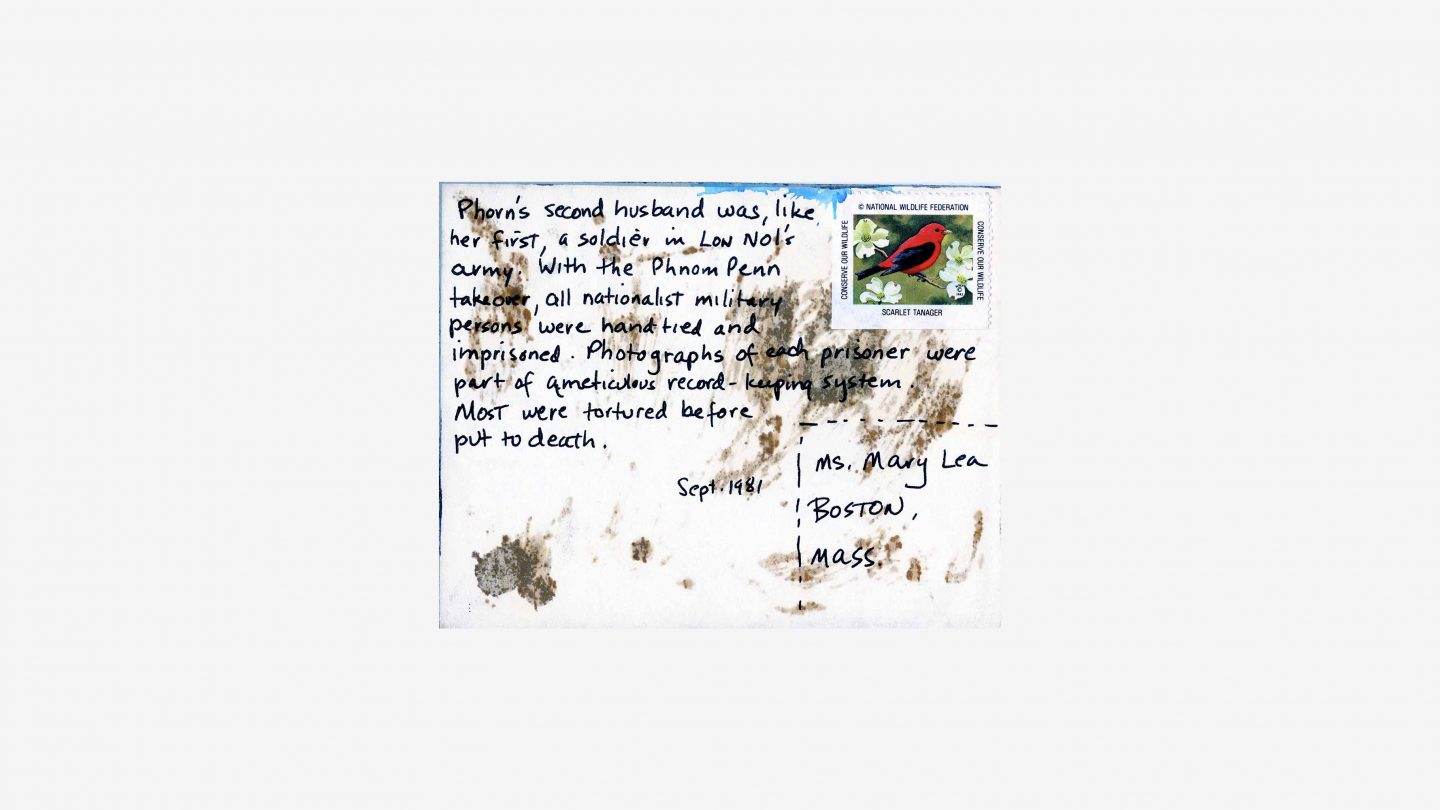

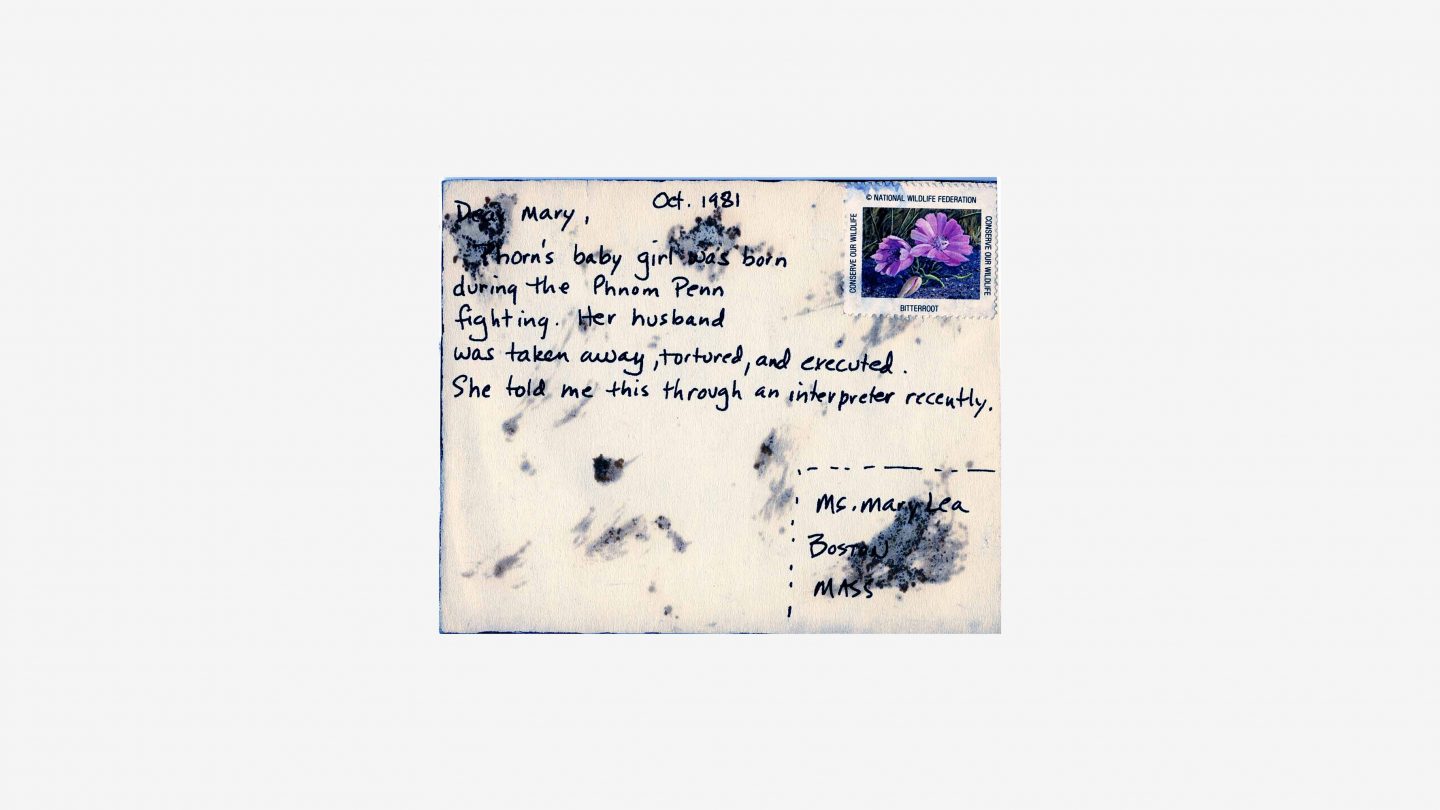

Among the Yann family papers housed in Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center is this hand-written family tree, outlining the names and ages of the EARS-sponsored refugees who arrived in Atlanta between 1981 and 1982.

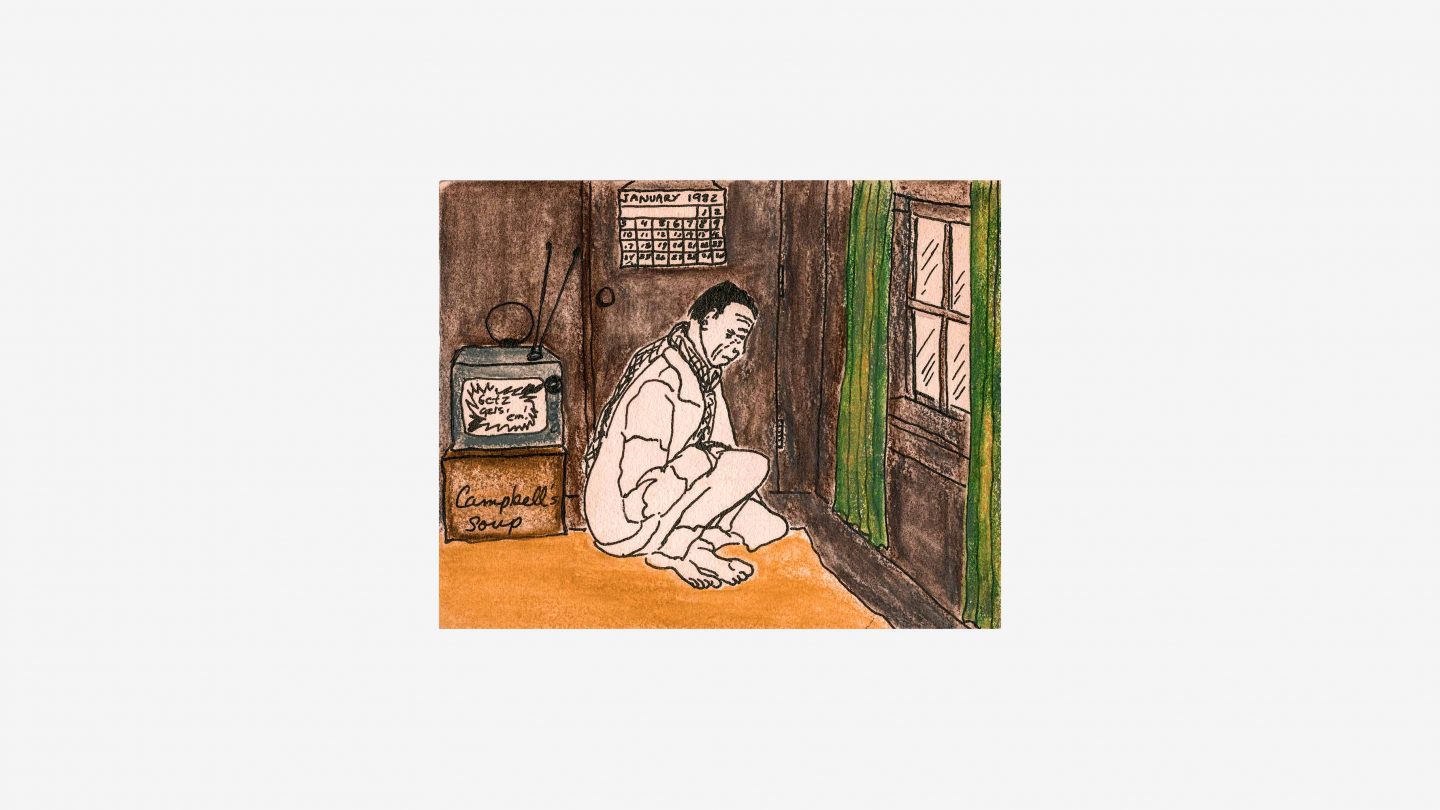

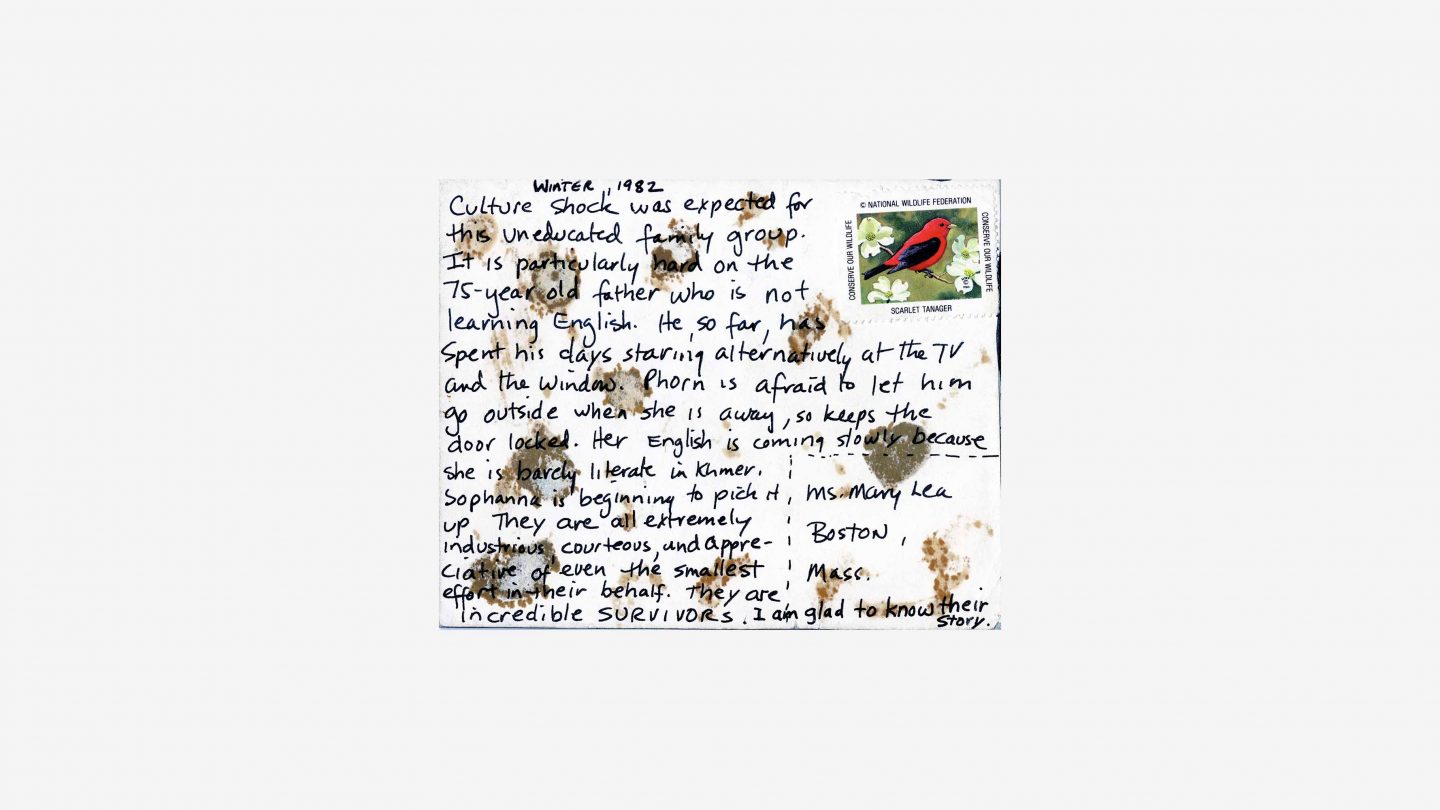

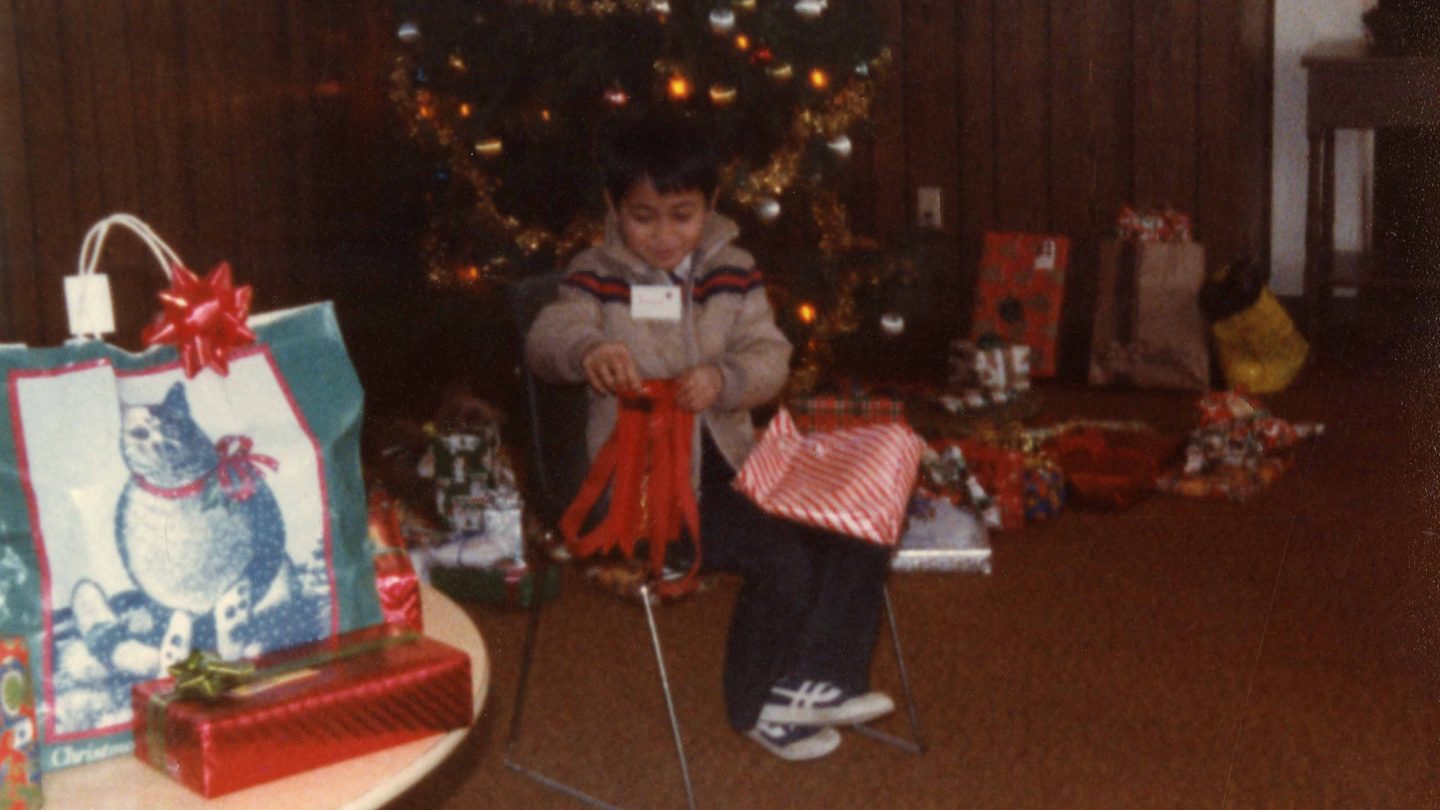

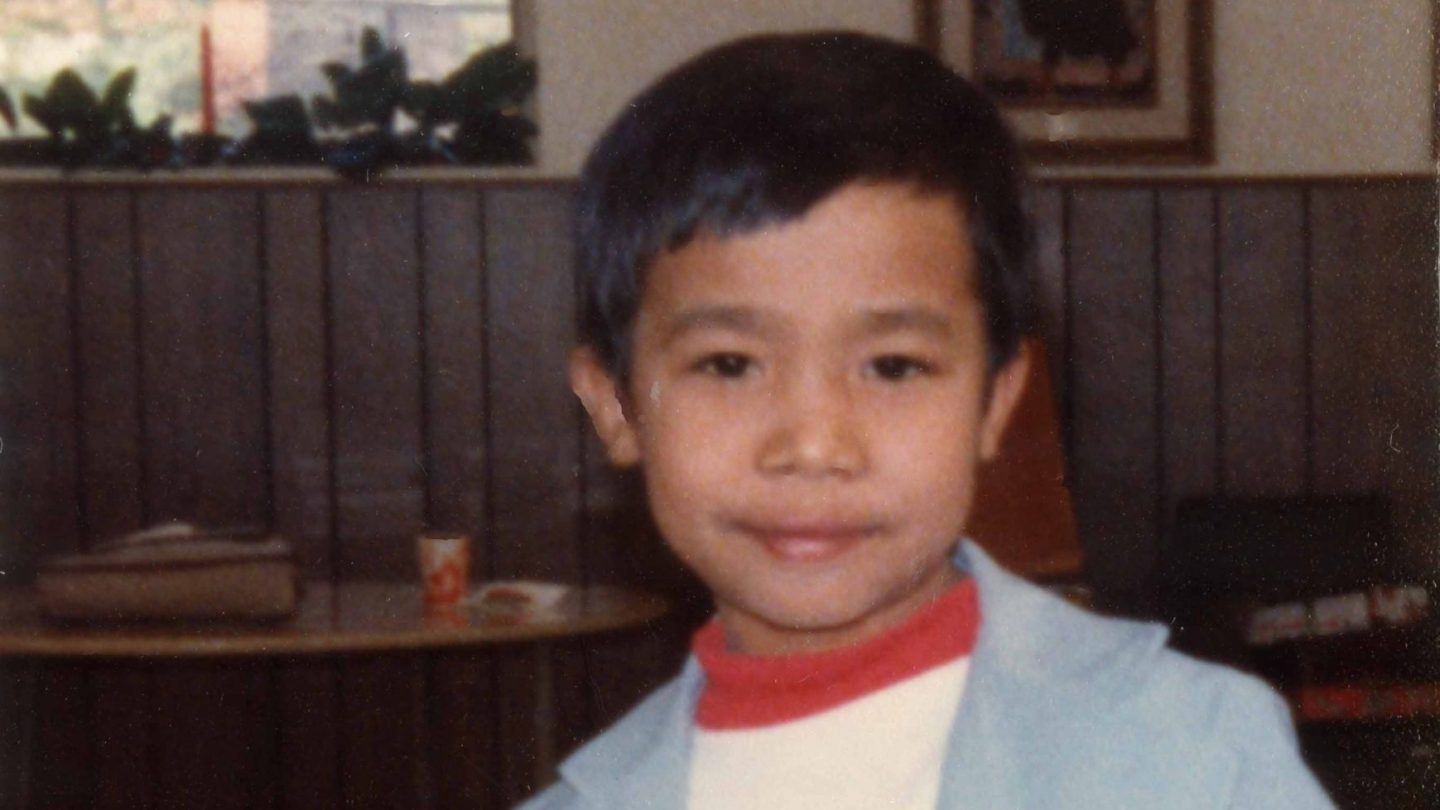

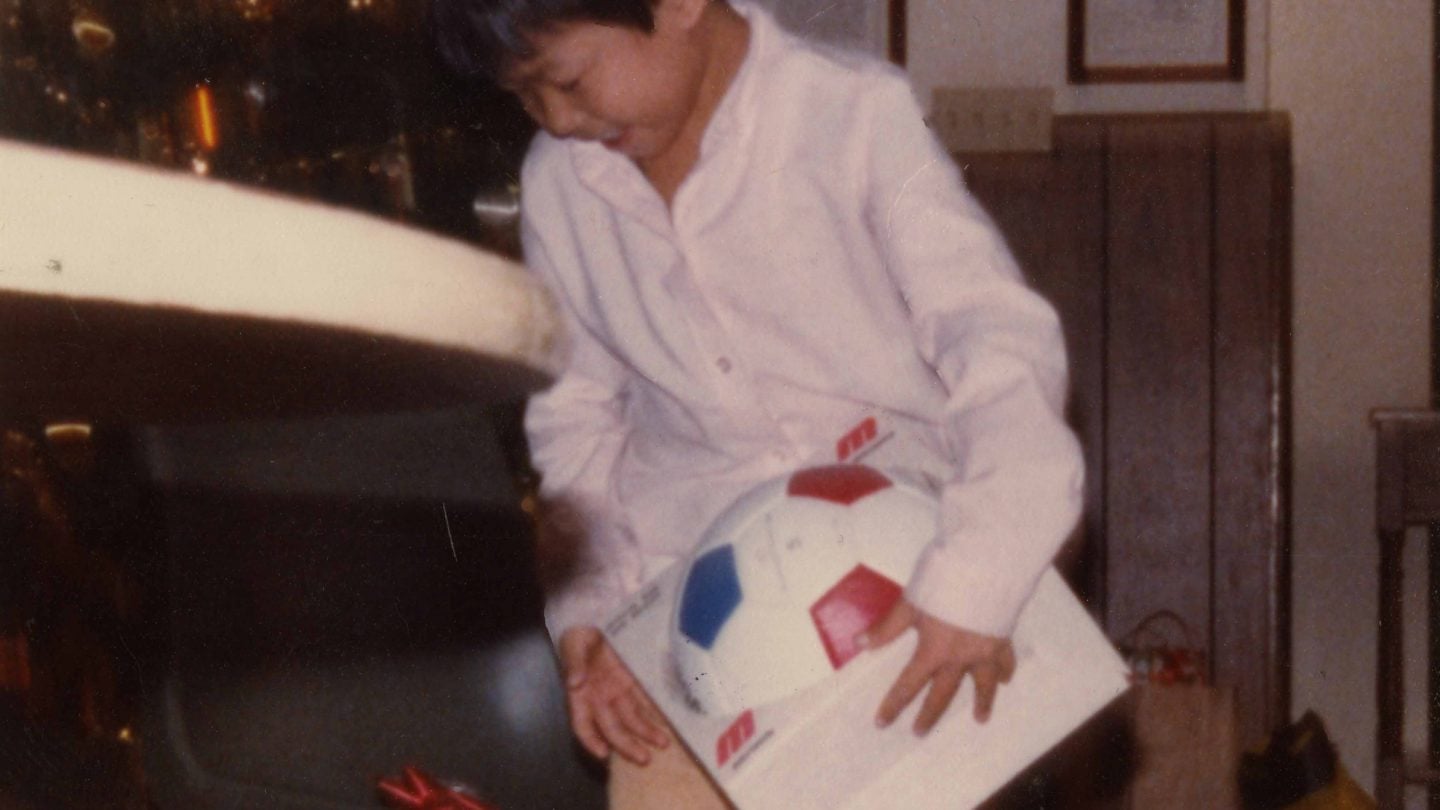

Speaking no English, all 13 members of the Mak family—ranging in age from two months to 70 years—moved into a church-owned home in downtown Decatur in the spring of 1982. They were joined shortly thereafter by Yann’s 75-year-old father, his sister, and her son. A 1982 Atlanta Constitution article on the family’s resettlement described their living situation, “as well as or better than the estimated 1000 Cambodian refugees living in the Atlanta area.”

Unsure about the status of relatives still trapped in Cambodia, all 16 refugees began to put down roots in Decatur.

Of the 5,800 Indochinese refugees who settled in metro Atlanta at the start of the 1980s, the majority were sponsored by church groups similar to EARS. According to the Atlanta Constitution, “most are entirely dependent on the sponsoring group for shelter and transportation during the first few months that they are in the country.” Like Yann, most arrived with little more than a set of clothes. Church World Service, which sponsored hundreds of Cambodian refugee families, dispensed a one-time payment of $1,200 to get each family on their feet. Refugees were eligible for the same federal assistance programs for which American families could apply. In 1981, a family of four could receive a maximum monthly payment of $216—roughly $625 adjusted for contemporary inflation.

“As far as we can tell,” said Brenda Wagner, former deputy director of the DeKalb Department of Family and Child Services in a 1981 interview with the Atlanta Constitution, “a very small minority of Indochinese refugees seek some sort of public assistance. …And our experience has been that those who ask for assistance don’t tend to stay on it very long.”

Bolstered by community support, Yann—a baker and fireman by trade—found work at the Gourmet Bake Shop on the square in Decatur, and later at the Pet Inc. Bakery Division where he made an hourly wage of $7.05.

Yann, Mareth, and their children received English tutoring from DeKalb County Schools.

Vanly and Chantou Mak pose with Ann Snyder (daughter of Chantou’s sponsors) at the wedding of Chany Mak in 1984.

In the 40 years since the Mak family arrived at Hartsfield International Airport, the city’s Asian American communities have cultivated thriving businesses, as well as culinary and cultural corridors.

There are now six Asian Americans who serve in the Georgia General Assembly.

This intersection of culture and representation highlights each of these communities’ diverse collection of languages, traditions, cultural heritage, histories, and other intricacies. Over the past decade, Atlanta’s immigrant population has continued to grow. According to the American Community Survey, there has been an estimated increase of 7,919 Asian Americans in the city since 2010—a rapid increase over previous decades.

For many Asian Americans such as the Mak family, a cultural resiliency has been a primary marker for success in this country. It’s this same resiliency that brings Asian American and other minority cultures face-to-face with the reality that fear and distortion—stoked by those who would rather teach fear than empathy—can turn what should be celebrated differences into targets.

Equipped with historical context, Atlanta History Center is focused on telling these multi-faceted stories about diverse communities and highlighting the experiences that connect us all.