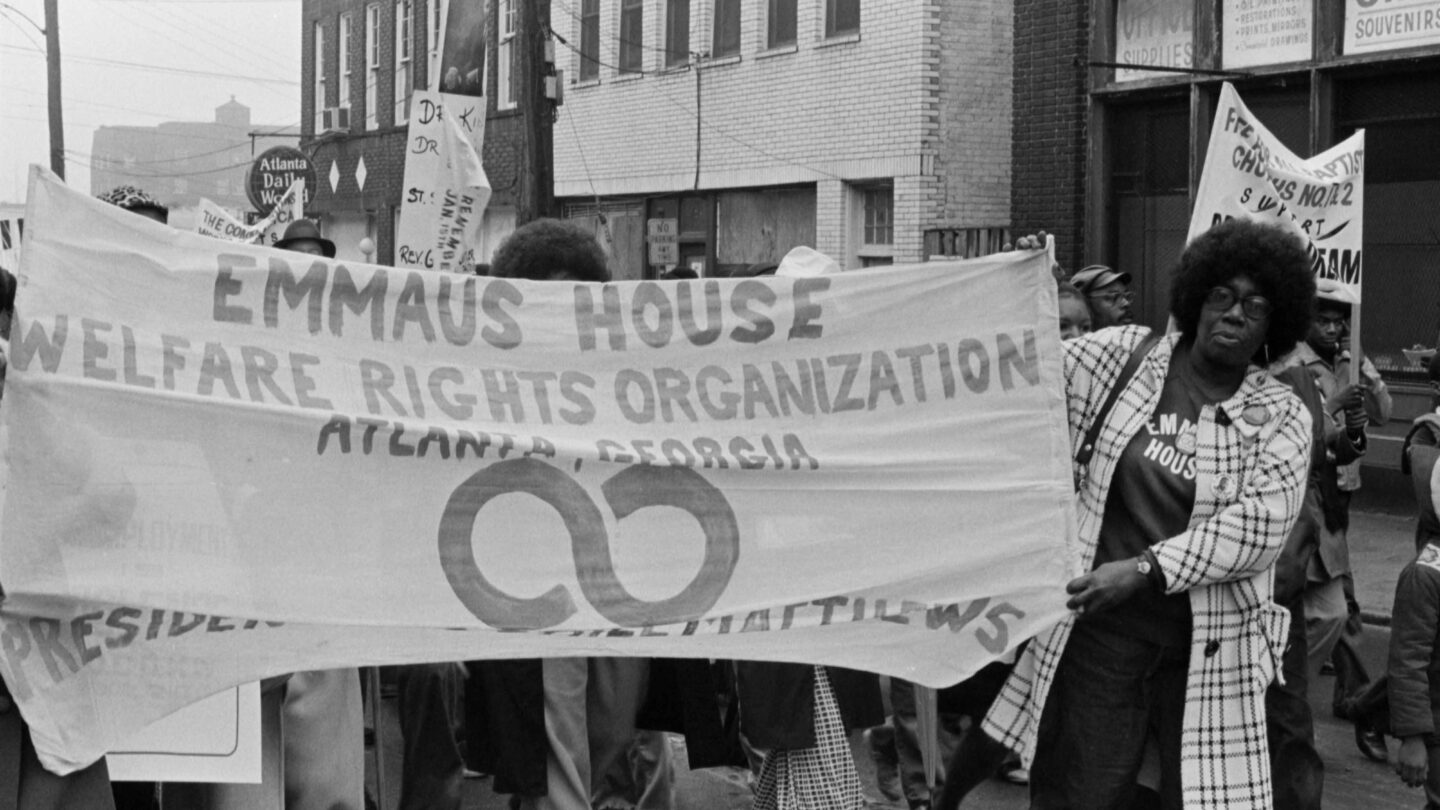

Ethel Matthews, the founder of the Atlanta Welfare Rights Organization, participating in the Martin Luther King Jr. Day march marking the slain civil rights leader’s 45th birthday, on Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, Georgia. VIS 101.470.012, Boyd Lewis Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

For more than fifty years, Ethel Mae Matthews worked tirelessly and advocated fiercely for greater welfare rights for the city’s poor and disabled. Her work at Emmaus House and beyond was peerless throughout the 1980s and 1990s in Atlanta and is exemplary of true grassroots social activism. Through unwavering negotiation, protests, picketing, adult education, legal challenges, and partnerships, Matthews utilized every method in her activist’s arsenal to dismantle the cycle of poverty that has plagued Atlanta’s most vulnerable residents for centuries.

“I’m rich with many things. Not with money, but with courage, with strength, with faith, with independence with my belief in god, and that makes me very rich.”

Born in Alabama and married by age 12, Matthews relocated to Atlanta in 1950 to raise her four children alone. The child of Black and Cherokee sharecroppers, Matthews was intimately familiar with widespread economic suppression of southeastern agricultural workers. Throughout her life, Matthews served as chairwoman of the Peoplestown Advisory Council, president of the Welfare Rights Organization, board Member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Georgia Citizens Coalition on Hunger.

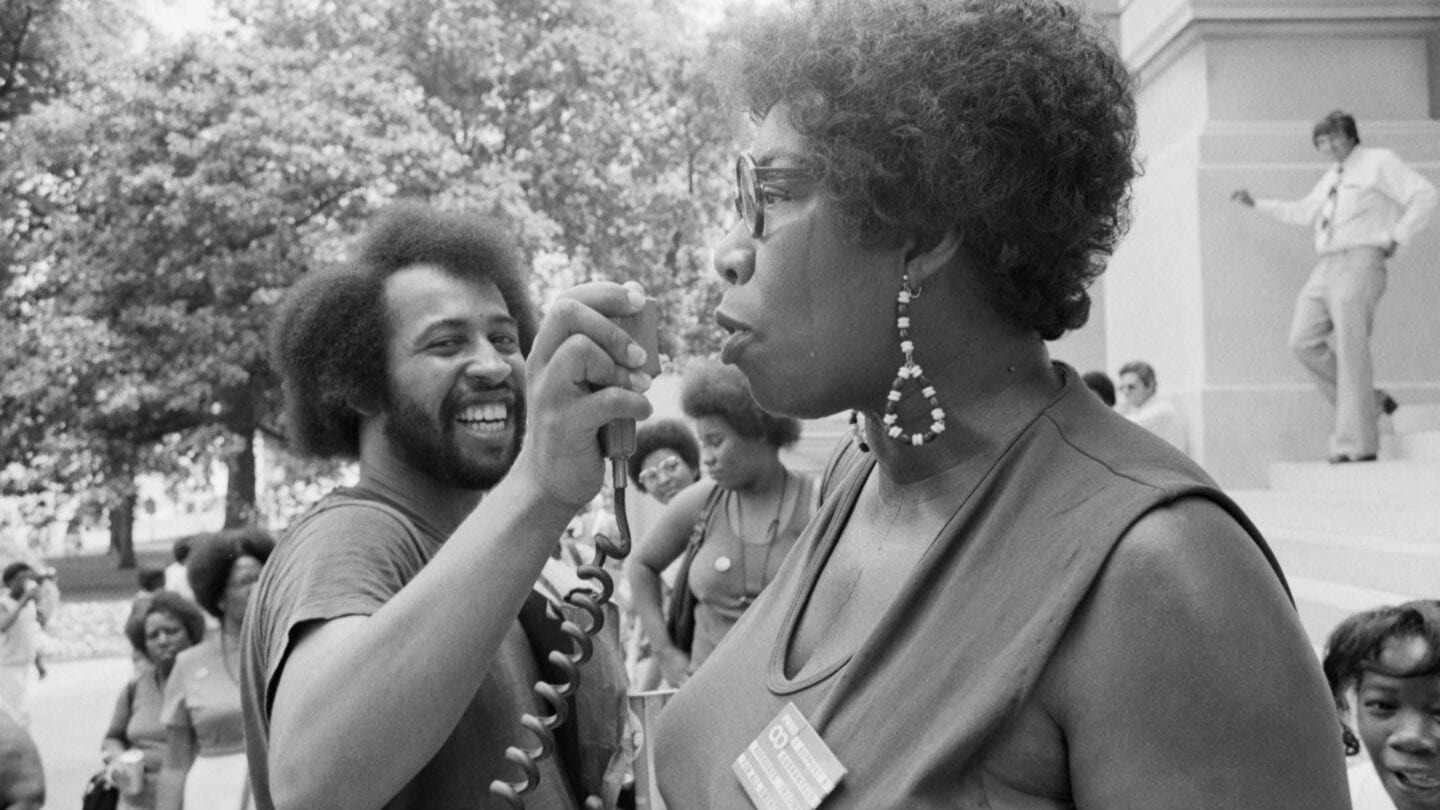

Ethel Matthews, the founder of the Atlanta Welfare Rights Organization, at Atlanta City Hall in downtown Atlanta, Georgia, for a meeting with the mayor. VIS 101.564.003, Boyd Lewis Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

She found a home in Peoplestown, south of Downtown Atlanta, and became a pillar of her beloved neighborhood. Matthews would later put her body on the line to defend it, physically blocking bulldozers set to raze the Peoplestown community center in the 1980s.

Perhaps most notable, however, was her work at Emmaus House. Founded in 1967 by Father Austin Ford, Emmaus House was a community advocacy hub and support center located in Peoplestown. One of a scant handful of welfare rights organizations in the urban core of Atlanta, Emmaus House served as a coordinating space for local social and economic justice activists, including Ethel Mae Matthews.

Ethel Matthews, founder of the Atlanta Welfare Rights Organization, during a rally against Governor George Busbee’s (not pictured) refusal to increase state welfare assistance levels, on the grounds of the Georgia State Capitol building in downtown Atlanta, Georgia. VIS 101.496.031, Boyd Lewis Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

A self-described “welfare mother,” Matthews sought to elevate the plight of others experiencing poverty. She headed Emmaus House’s first welfare rights committee. Under her leadership, residents of several low-income Atlanta neighborhoods founded chapters of the National Welfare Rights Organization and used Emmaus as their common meeting place.

After attending adult education classes in Atlanta to earn her GED, Matthews became an outspoken supporter of improved educational facilities for the city’s Black children, citing illiteracy as a key proponent in the ongoing oppression of the nation’s poor.

In the late ‘60s, along with local parents, Matthews helped to transfer nearly 400 young, Black students from under-funded, under-resourced schools in South Atlanta to schools in more affluent, predominately White neighborhoods. She also helped to establish a bussing system to get those students to their new schools.

“Atlanta is not too busy to hate. Because if it was too busy to hate, you wouldn’t have no children going to bed crying for food every night.”

Matthews played an integral part in the foundation of city-wide tenants’ rights group, Tenants United for Fairness (TUFF) which—among other things—successfully picketed the Atlanta Housing Authority for better lease agreements, improved property conditions, and a grievance review procedure that was the first of its kind and served as a blueprint for similar processes in public housing units nationwide.

In 1973, she ran for city council “to bring about a change for all poor peoples, regardless of race, creed, or color.” Because she couldn’t pay the $500 filing fee, Matthews was denied a spot on the ballot. County offices told her that she could waive the fee if she could collect 1,200 signatures supporting her candidacy. She returned three weeks later with 25,000.

Though she didn’t win the 1973 election, or her second bid in 1981, Matthews’s campaign increased visibility for impoverished communities that had long been overlooked by local government.

“I don’t let nobody, I mean nobody, tell me what I can’t do. Or what I can do.”

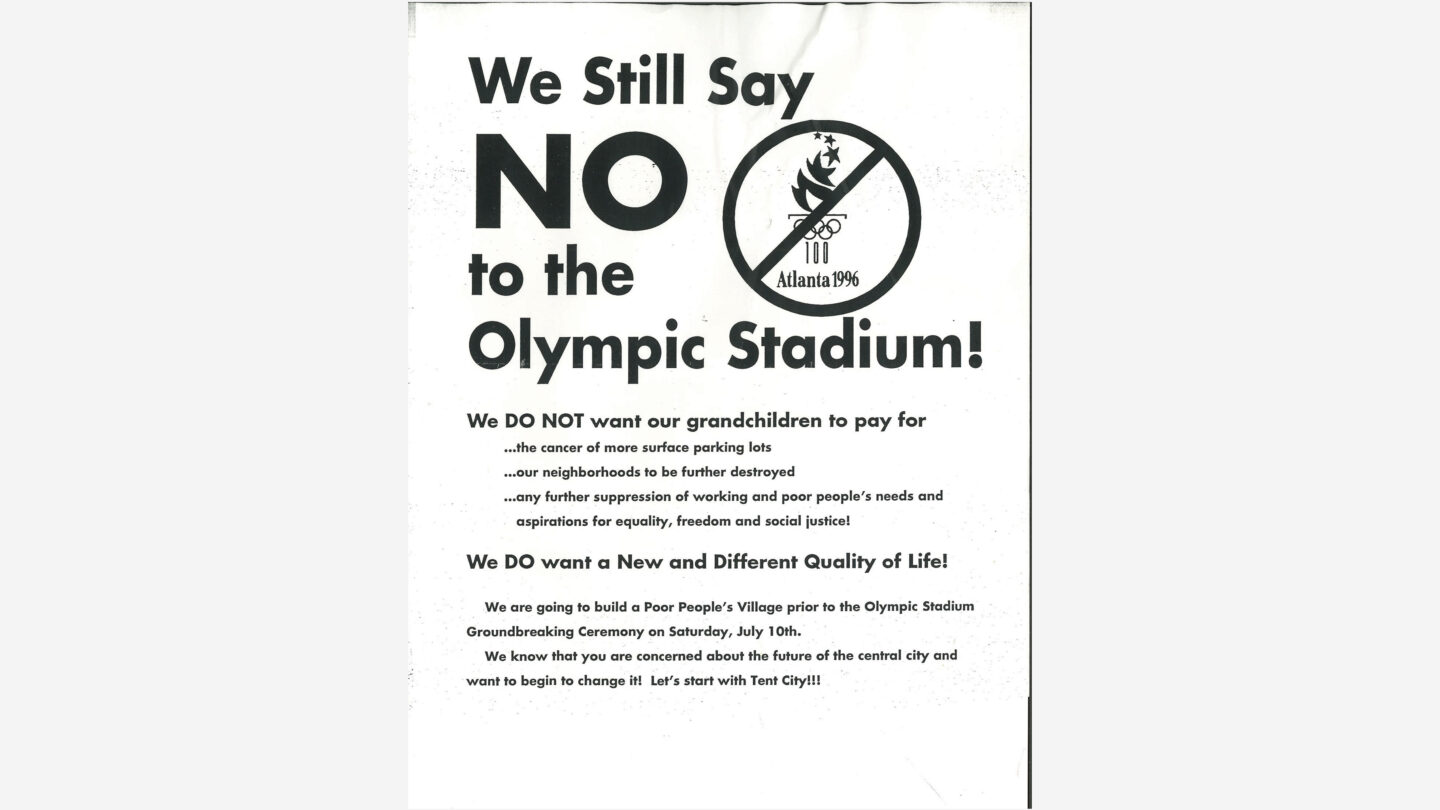

Displaced by construction of the original Fulton County Stadium, talks surrounding the 1996 Olympic development strategies angered Matthews once again. She founded and led Atlanta Neighborhoods United for Fairness (ANUFF) in 1993 in a campaign against the development of the Olympic Stadium.

ANUFF organized pickets and protests at Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games headquarters. Their initial goal was to change the location of the planned stadium, and when that failed, the group erected a tent city at the stadium’s construction site and protested the official groundbreaking.

This tactic, like Matthews’s other demonstrations, ensured that organizers and city officials (and news cameras) couldn’t miss the concerned residents, and that their demands would need to be addressed before organizers could regain a clear construction site. It was WIlliams and ANUFF who negotiated with Olympic leaders to ensure the stadium’s presence could benefit their neighborhoods, from parking income to labor agreements.

Ethel Matthews, the founder of the Atlanta Welfare Rights Organization, at Emmaus House in the Peoplestown neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia. VIS 101.223.010, Boyd Lewis Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center

To learn more about Matthews’s work to shrink Atlanta’s class disparity, visit Atlanta ‘96: Shaping an Olympic and Paralympic City.

Atlanta Journal Constitution | Ethel Mae Matthews Obituary

Washington University | Interview with Ethel Mae Matthews for Eyes on the Prize II

Kolumn Magazine | Ethel Mae Matthews and the Emmaus House in Atlanta

Ethel Mae Matthews Place | About Our Namesake