View of an Atlanta University Center student protest of the Vietnam War in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1970. Boyd Lewis photographs, VIS 101, Kenan Research Center.

The politics of age have driven our nation’s democratic engine for more than a century. Young people, dissatisfied by the world laid before them by previous generations and eager to mold it to their own visions have, time and again, taken up the torch and blazed their own trail through history.

Children, teenagers, and young adults organized their own social justice campaigns before, during, and after the civil rights campaigns led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As early as the 1870s, Black students mobilized to protest inequity. Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, youth activism served as the backbone of the Civil Rights Movement. NAACP Youth Councils held picket lines to protest injustices from segregated department stores and lunch counters to mob violence and lynching. The Birmingham Children’s Crusade of 1963 saw participants as young as four being beaten by police, arrested, and held in jail for days at a time. Sit-ins, both planned and spontaneous, carried out by Atlanta University Center students worked to flood county jails, overwhelm the system, and eventually desegregate Atlanta’s lunch counters.

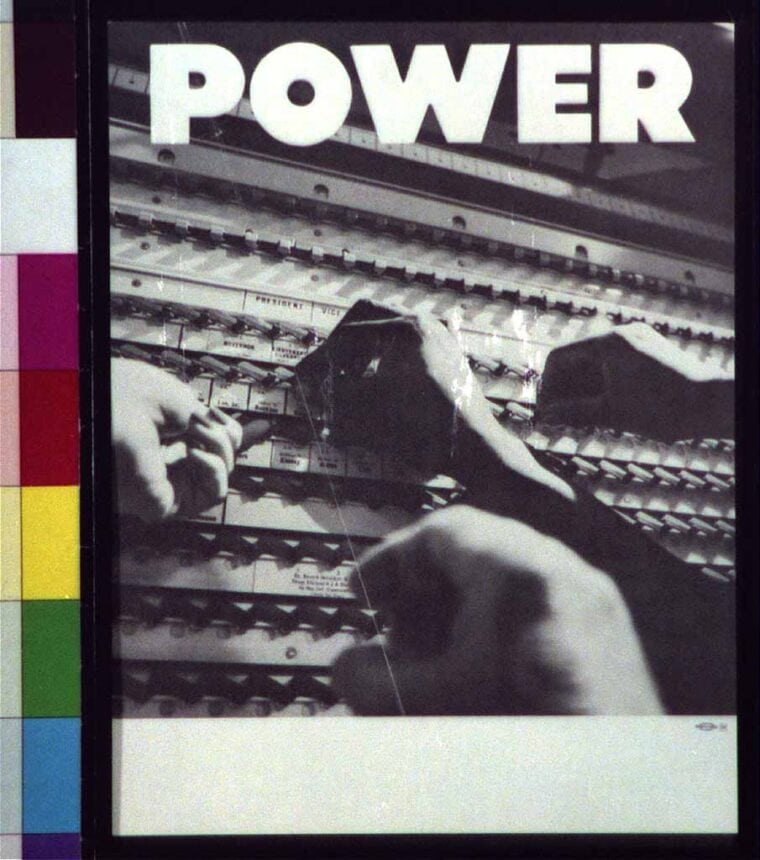

Voting is Power, Yanker Poster Collection (POS 6 – US, no. 785, Library of Congress)

Members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the NAACP’s youth branches demonstrated a willingness to take risks and displayed a level of urgency that their older counterparts did not always achieve. Across the Southeast, young people embodying the philosophy of nonviolence carried out peaceful and effective protests that led to lasting legislative change.

In his 2014 book, A Child Shall Lead Them: Martin Luther King Jr., Young People, and the Movement, Rufus Burrow Jr. wrote:

“Martin Luther King never lost faith in young people and their ability and determination to help move this society in the direction of the beloved community.”

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

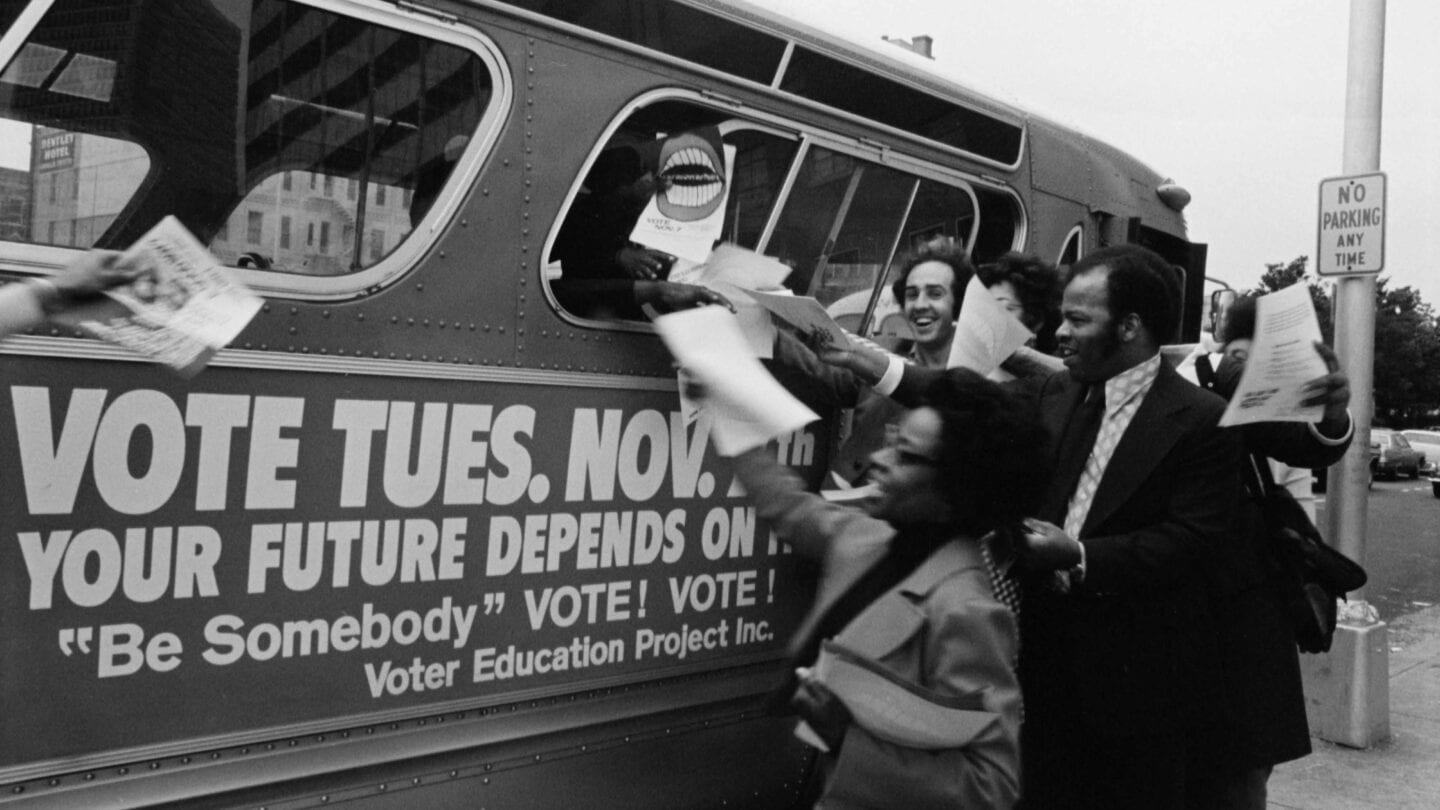

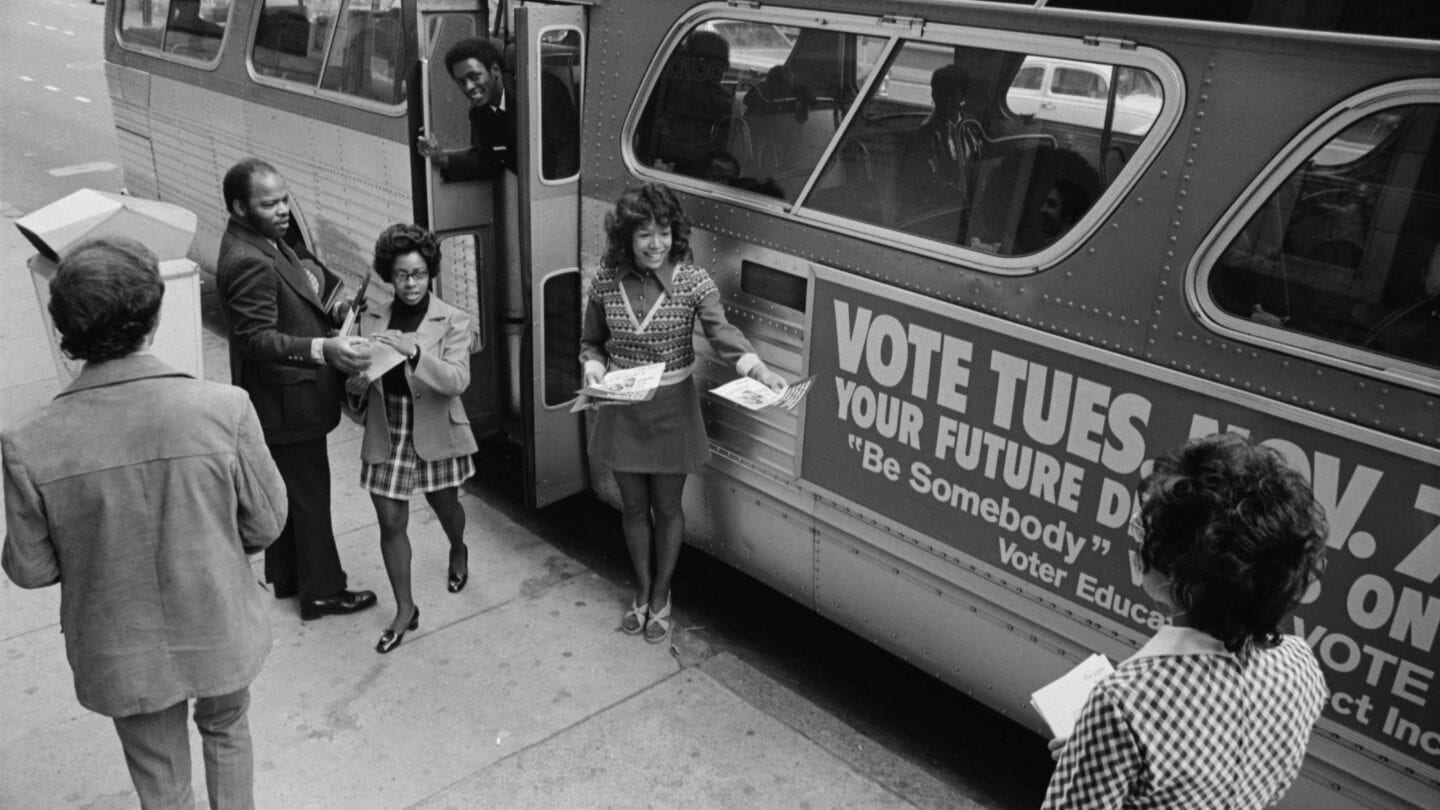

Emphasizing themselves as outright “citizens” rather than “youth,” young civil rights organizers led campaigns throughout the South aimed at registering underserved potential voters.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was a recipient of financial support from the Voter Education Project (VEP). Founded at Fisk University in 1901, SNCC found a dedicated base of both Black and white college students willing to put their bodies on the line for social justice.

In his memoir, Walking with the Wind, former SNCC chair and future Congressman John Lewis (who was 20 at the time of SNCC’s founding) recalled voter registration being a “top priority” for SNCC in the early 1960s. Throughout the South, SNCC rallied approximately 200,000 volunteers during the summer and fall of 1961, “all aimed at bringing America’s invisible Black vote out of the darkness of fear and repression.”

Organizer Charles Sherrod (age 21) and SNCC staffer Cordell Reagon (18) traveled to Terrell County, Georgia, one of the most racially oppressive regions of the state, to establish a base of operations. Alone in the former slave-trading center of Albany, Sherrod and Reagon put their lives at risk to register voters.

“Lives were on the line. There was no question about that.”

Twenty-six-year-old Bob Moses traveled into McComb, Mississippi, as part of SNCC’s first voter registration drive. Mississippi was notoriously hostile towards people of color. At the time of SNCC’s dispatch, only 5% of the state’s eligible Black voters were registered. Literacy tests, poll taxes, and racial terrorism prevented potential voters from fulfilling their rights as citizens to vote.

Putting his life at risk, Moses went from door-to-door distributing voter registration forms. A young man himself, Moses was often accompanied by even younger activists—honors students from the local high school. These students, along with Moses, prepared Mississippians for questions they might encounter on literacy tests, explained voter requirements, and accompanied African Americans through hostile county courthouses so that they might add themselves to the voter rolls.

“White Mississippians had never seen it,” wrote Lewis. “And they didn’t like it. Beatings, arrests, and deaths would begin that fall, and things would get much worse before they got better.”

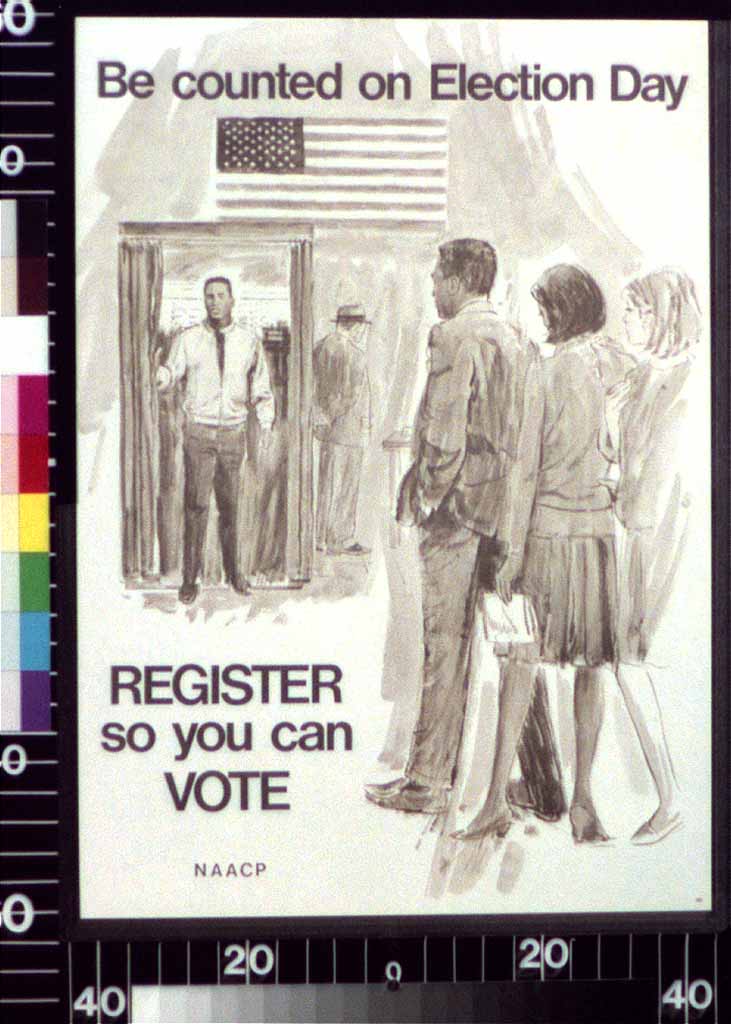

NAACP-sponsored Voter Registration Poster, Yanker Poster Collection (POS 6 – US, no. 1009, Library of Congress)

Securing the Right to Vote

The groundswell of youth activism helped to propel the Civil Rights Movement from the fringes of political discourse into the spotlight of American culture. Newly enfranchised Black voters in the South—many of them under the age of 30—continued to make their voices heard. Ten years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1965, the number of registered eligible Black voters in the South soared from 2% to 60%. In that same period, the number of Black elected officials in the region shot upwards from less than two dozen to more than a thousand.

Rufus Burrow Jr. wrote, “it was children and young people who boldly led the way in many civil rights campaigns, who energized the movement at strategic movements. They asserted themselves, making it clear once and for all that they were fully aware of the racial discrimination and its adverse effects on them.”

The Next Chapter

In the 21st century, youth activists continue to construct a better, more equitable future for themselves.

In Atlanta, young people reinvent the city with fervor. During the 2020 presidential election, more young people turned out to vote in Georgia than they did anywhere else in the United States. Between the November election and the January 5, 2021, runoff for the country’s two undecided senate seats, approximately twenty-three thousand Georgians turned eighteen. At least four in 10 voters who registered after the November 3 election in Fulton, Gwinnett, Cobb, and DeKalb counties were under 30 years old.

To get out the vote in this election, zillennials utilized a tool not available to youth organizers of the ‘60s: the internet. During a pandemic when door-to-door canvasing could prove hazardous to public health, youth volunteers made their voices heard on Zoom calls, text chains, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok. Willing to adapt to changing times and meet their peers where they were, young Georgians found ways to connect with the newest generation of eligible voters.

National news may distract but cannot detract from the history made by young voters in the 2021 Georgia senate runoff election.

Photo by Nathan Posner for Atlanta Corona Collective (Kenan Research Center at Atlanta History Center)

By organizing, mobilizing, and strategizing, they played an integral role in electing Reverend Raphael Warnock, Georgia’s first Black senator, and Jon Ossoff, Georgia’s first Jewish senator. Bridging the gap between themselves and the next chapter of history, these young voters helped make it possible to send a millennial to Congress: when sworn in, Jon Ossoff (33) will be the youngest Democratic senator elected to office since Joe Biden joined the senate at age 30 in 1973.

The outcomes of the 2020 and 2021 elections are not a fluke—they are the culmination of more than 150 years of bold, unwavering youth activism in the face of adversity.

Additional resources.

Hartford, Bruce. “Sit-Ins and Voter Registration in 1960.” Race, Poverty & the Environment, vol. 19, no. 1, 2012, pp. 15–15. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41762526. Accessed 7 Jan. 2021.

Patton, Randall L. “Southern Regional Council.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 20 February 2013. Web. 07 January 2021. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/government-politics/southern-regional-council

Chartier, Courtney E. “Voter Education Project.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 30 August 2013. Web. 06 January 2021. https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/voter-education-project

Faulkenberry, Evan. Education as Activism: The Voter Education Project in the Civil Rights Movement | Process: A Blog For American History from Organization of American Historians http://www.processhistory.org/voter-education-project/

“Voter Education Project (VEP).” The Cambridge Guide to African American History, by Raymond Gavins, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016, pp. 287–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316216453.298

Scott, Holly V. “Student Citizen, Part I: The Civil Rights Movement.” In Younger Than That Now: The Politics of Age in the 1960s, 18-32. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. 2016. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1hd19ff.5. Accessed 8 Jan. 2021.

Bynum, Thomas. NAACP Youth and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1936-1965. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2013.

Burrow Jr., Rufus. A Child Shall Lead Them: Martin Luther King Jr., Young People, and the Movement. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014.

Atlanta Magazine | Flashback: How student sit-ins in downtown Atlanta sparked change in the 1960s

CNN Politics | Young people are getting out the vote in Georgia — from thousands of miles away

NBC News | Gen Z is using TikTok to encourage youth voter turnout in Georgia’s runoffs

NBC News | Thousands of voters registered for the Georgia Senate races. Who benefits?

New York Times | Phone Calls, Texts and Tinder — Georgia Campaigns Court Young Voters

NPR | Activists Begin Registering Young Voters In Preparation For Georgia’s Runoff Election

Georgia Voter Registration Statistics | Georgia Secretary of State

We Had Sneakers, They Had Guns: The Kids Who Fought for Civil Rights in Mississippi | Library of Congress

Youth in the Civil Rights Movement | Library of Congress